Imagine living in a crowded city of 3.1 million people and learning that amidst this human world, the huge buildings, the maddening crowd, and the deafening sounds lies a small, happy, and peaceful refuge where wild leopards rule.

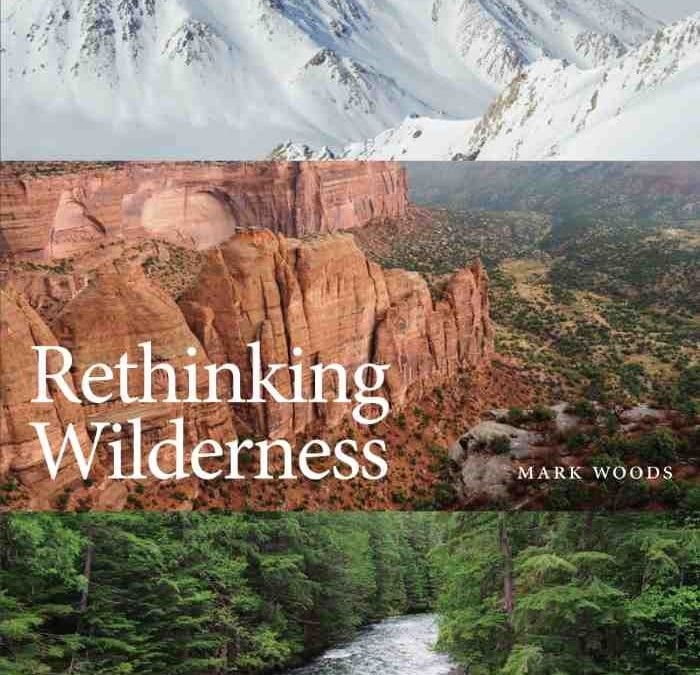

Managing recreational opportunities and resource use while simultaneously working to conserve unique ecosystems for future use is particularly challenging in a vast and varied landscape such as Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

Field stations have provided opportunities for place-based learning in protected areas for well over a century (Lohr and Stanford 1996). Today, they continue to allow for the study of current biological problems including climate change and the loss of biodiversity (Baker 2015).

From the reintroduction of lynx and ospreys to taxing the tourists, the English Lake District is at the center of various debates on the protection of natural and cultural heritage and wildlife.

When considering nature conservation across the globe from my lifetime of experience working with nature and people in India, I wonder why we Indians have failed to export our attitudes, including a reverence for life, to the West.

For the last several decades, a debate has raged over whether the practice of wilderness preservation is meaningful, worthwhile, or even morally defensible in the contemporary world.