The backwaters of the Gosekhurd Dam project have good fish populations and the community has exclusive rights for fishing here. photo credit © Dr. Parvish Pandya / Sanctuary Nature Foundation.

Nature Needs Half at Work: Indian Villagers Working through “COCOON”

International Perspectives

August 2019 | Volume 25, Number 2

When considering nature conservation across the globe from my lifetime of experience working with nature and people in India, I wonder why we Indians have failed to export our attitudes, including a reverence for life, to the West. Why did we instead import developmental attitudes that treat nature as a resource rather than as a source? In my opinion, changing this one “attitude” could be a catalyst for the success of the ambitious and necessary vision and practice called Nature Needs Half (Sylven 2011; Locke 2018). The Nature Needs Half movement calls for protecting 50% of the planet by 2030, in order to turn the tide in favor of Earth’s life support systems and to transform society’s relationship with nature, one ecoregion and country at a time.

Adopting the philosophy of Nature Needs Half and realizing its imperatives is easier said than done, but it can and must be done. Perhaps the very first step needed is to build bridges of collaboration between the different sectors and perspectives working to improve human life and/or to protect wild nature that previously and currently have been siloed from one another. Take the case of the government, corporate, and social sectors. All three, irrespective of country or culture, at some point find themselves at loggerheads with possibly the least supported of all sectors – biodiversity and nature conservation. This certainly is India’s reality, and into this reality now comes climate change and its destabilization of virtually all human endeavors in its path.

But all is not lost.

Nature is self-repairing, and Planet Earth has not yet reached a point of no return. We still have time to pull away from the environmental precipice toward which Homo sapiens are so resolutely headed. This problem is not unique to India, but it affects India deeply because 1.3 billion people on the Indian subcontinent have virtually run out of time, while the climate clock ticks away relentlessly.

A major gap in the collective efforts of the people of the Indian subcontinent has been missing the biodiversity-conservation imperative in human rights, climate change, and economic circles. With the exploitation of resources being equated with “development,” most conservation and ecosystem management attempts have been predominantly corralled into the confines of formal Protected Areas (PAs) declared by the government under statutory provisions. When these areas are properly managed, nature often can and does flourish. In India, tiger populations have increased and water sources that once ran dry soon after the monsoon have become perennial. But, outside of such “nurseries of biodiversity,” lands continue to be stripped bare, leaving the soil impoverished and the biodiversity minimal.

In a densely populated country such as India, where people depend heavily on the bounty of nature, the extirpation of biodiversity across almost 90% of the subcontinent has left people with little option but to look toward the PAs for resources such as firewood, fodder, wild fruit, edible flowers, and even marginal farming. This has led to conflicts between local communities and park managers. And when this occurs, ecosystems vanish, as do the ecosystem services and species upon which the quality of human life depends.

Despite centuries of destruction, India continues to harbor some of the world’s finest biodiversity hot spots. But these are now largely disconnected pencil dots on the Indian subcontinent. If we are to have any hope of restoring half of India’s landmass to biodiverse status, the pencil dots must be converted into biodiverse “ink-blots.”

Sanctuary Nature Foundation and COCOON

This is where the Sanctuary Nature Foundation’s Community Owned Community Operated Nature (COCOON) Conservancies come into play. The central tenet of a COCOON conservancy is that it is designed as a social upliftment program that creates sustainable, dignified livelihoods, with enhanced biodiversity being a measurable, collateral benefit.

Acutely aware that solutions to alleviate farmer stress and improve the relationship between people and parks was floundering, the Sanctuary Nature Foundation decided to demonstrate that it was possible to rewild abandoned and failed farms located right next to sanctuaries and national parks. The pilot project at Gothangaon village, next to the tiger forests of the Umred Pauni-Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary, has turned out to be a success. Here, 37 families have stopped farming and allowed the forest to regenerate on their own land holdings. For four years, the sanctuary found the resources to compensate the farmers equal to what they would have earned had they farmed. Soon nature did what nature does best… repair itself. Palatable grasses and bushes and then trees began to colonize their land. Birds, herbivores, and carnivores followed suit. A way was worked out to gift families homestays with titles in their names, which they in turn would entrust to the management care of BFSL for 30 years. Everyone came out winning. The tigers got the space they needed.

Locals whose farms were in a dire state got compensated for not farming, and as health returned to their holdings, their land values rose. In the process, carbon was sequestered from the atmosphere and to a great extent the seeds of human-animal conflict resolution were sown. From a Yamdoot (Grim Reaper), the tiger turned into their Annadata (Horn of Cornucopia). The Sanctuary Nature Foundation is now looking to scale this model and take it to diverse ecosystems, similar to the way as Project Tiger did in 1973, but with people being the primary beneficiaries of rewilding. A huge collateral benefit of the COCOON Conservancy initiative is the enhanced security of cores, buffers, and corridors of biodiverse landscapes. Other benefits, such as clean air, improved water regimes, climate control, and enhanced farm productivity of surrounding farm holdings have not even begun to be calculated.

In the words of Sunil Mehta, conservationist and one of India’s most successful wildlife lodge owners, “Sanctuary Nature Foundation’s COCOON Conservancy concept is set to disrupt the existing wildlife tourism model in India by turning it from one that keeps people out into one that sees people welcome wildlife as a source of income and pride. What is more, the visitor experience is going to be dramatically improved.”

The Rewilding Strategy

Inspired by the blueprint set out in 1971-72 by the first director of Project Tiger, Kailash Sankhala, Sanctuary Nature Foundation chose to follow a rewilding selection strategy based on resurrecting different biogeographic zones. Our pilot project in the Gothangaon village in the Nagpur District of Maharashtra, India, is expected to be open to the public by the end of 2019. It has taken five long years to identify issues and create the best solutions, but today we have a successful model. What formerly were distressed farming communities living immediately adjacent to tigers in the tropical, dry deciduous forests of the larger Tadoba landscape are now far better off and more secure, even as plants, insects, birds, carnivores, and herbivores have reoccupied lands that had been stripped of almost all biodiversity.

But it was only after scrutinizing the results of an extensive social survey involving 1,000 farming families, undertaken jointly in 2014 by the Bombay Natural History Society and the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, that the Sanctuary Nature Foundation honed in on the Gothangaon village in Maharashtra.

Three selection criteria are examined in the creation of a COCOON Conservancy:

- COCOON Conservancies must be located on marginal or failed landholdings on the edges of high biodiversity areas. These areas attract a fair number of visitors in search of nature experiences (crucial to creating revenue streams without biodiversity loss).

- Communities must retain ownership of their lands. But their small, contiguous holdings must remain unfenced and be aggregated through cooperatives to form rewilded land parcels of 100 acres (40.5 ha) or more, with the goal of expanding the rewilding process onto much larger contiguous areas.

- Sanctuary Nature Foundation’s primary role involves locating potential sites, orienting, and then linking communities with trustworthy lodge and hospitality professionals. These professionals must be willing to invest, build, operate and transfer, and accept terms that favor the community,

While communities retain ownership of their own lands and the newly constructed homestays, in return they would offer management agreements to professionally run the homestays for periods ranging from 20 to 30 years, which would allow the capital invested in setting them to be recovered. The Sanctuary Nature Foundation would be jointly appointed as Ecological Auditors by the community and the homestay professional to ensure that neither drifts away from the original rewilding objective.

The first pilot project is located in Vidarbha, which has the dubious distinction of being the “farmer suicide capital” of India. Here, abutting the large reservoir of the Ghosikurd Dam and the 189 sq. km (73 sq. miles) Umred-Pauni-Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary (UPKWS), is a parcel of land that local farmers have rewilded under the guidance of the sanctuary during the past five years (Sanctuary Asia 2016a). We now propose to involve the villages of Rajoli and Pandhargota, abutting Gothangaon. By all indications, this initiative should fructify within the next 18 months or so to create a contiguous COCOON Conservancy of roughly 500 acres (202 ha) next to the biodiverse UPKWS hinterland.

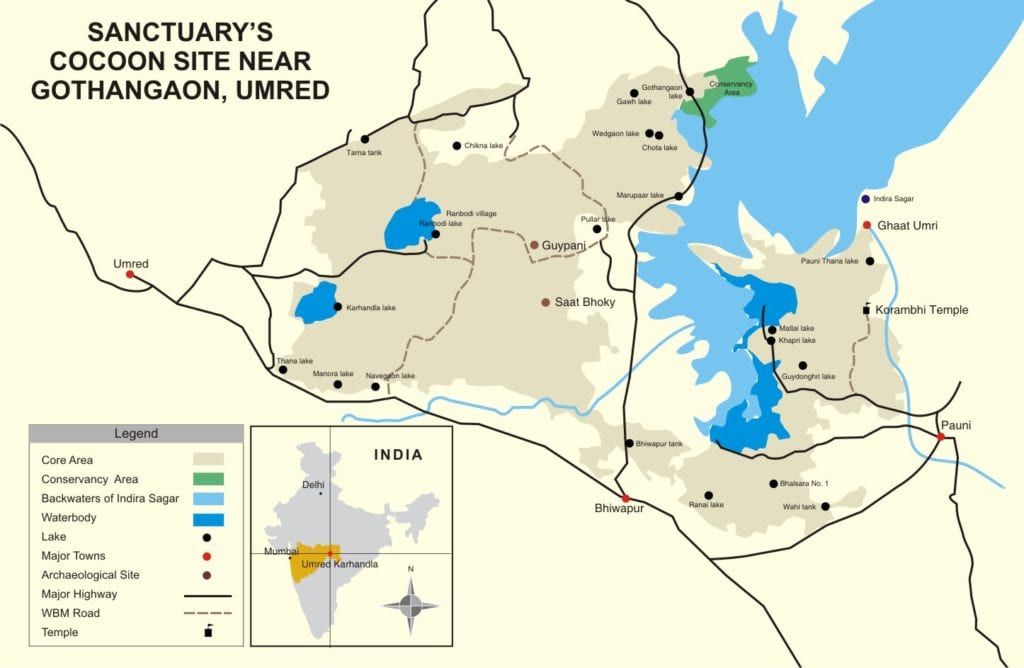

Figure 1 – A notional map showing the location of water impoundment from Gosekhurd dam, the backwaters, and the adjoining COCOON Conservancy site. Photo courtesy of Sanctuary Nature Foundation.

Figure 2 – Farmers’ cooperative assembles at talks in January 2015, with Sanctuary’s Bittu Sahgal (in green), during the setting up of COCOON. Photo courtesy of Sanctuary Nature Foundation.

Where wildlife was once driven away from their marginal farms, today tigers, deer, monkeys, wild pigs, and birds are welcomed as “magnets” that attract paying ecotourists in search of real nature experiences. The Sanctuary Nature Foundation and the COCOON Conservancy form a key part of a wildlife corridor that acts as a staging ground for tigers moving across a landscape that extends over 3,000 sq. km (1,158 The sq. miles). The COCOON pilot itself comprises privately owned land outside the buffer zone of the protected UPKWS forest, which is managed by the Maharashtra State Forest Department.

Based on our initial success, and having now won social, biological, and financial proof of concept, we are poised to carry the COCOON Conservancy Project to other biogeographic zones including alpine and subalpine Himalayan habitats in Kashmir, brackish water wetlands north of Odisha’s Chilika Lake, moist deciduous forests in the Central Indian highlands around the Pench-Kanha tiger corridor, tall-grass swamplands alongside the Brahmaputra river in Assam, and the world’s largest mangrove forest – the Sundarban in the 24 Parganas, West Bengal.

Figure 3 – The wetlands of Navegaon Reservoir to the northwest of the COCOON area attract thousands of migratory waterbirds. Photo by Dr. Parvish Pandya/Sanctuary Nature Foundation.

Building Capacity Through Collaboration

Credit for the financial proof of concept came from tourism professional and wildlife conservationist Sunil Mehta (Sanctuary Asia 2018), an entrepreneur responsible for creating and running some of India’s most successful wildlife tourism enterprises including Nature Farms and the iconic Tree House Resort (http://www.treehouseresort.in/) on the outskirts of Jaipur City, and the Bamboo Forest Safari Lodge, just outside the Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve. While the Sanctuary Nature Foundation gave birth to the idea of Community Nature Conservancies, it was Mehta’s foresight that gave shape and form to the formula that enabled the sanctuary’s idea to plot a course through the complicated land laws and emotive issues surrounding collective land ownership in India. Critical help also came from Praveen Pardeshi, a high-ranking Indian Administrative Services Officer who convinced forest officials and the chief minister of Maharashtra that the potential for rewilding failed and marginal farms (agricultural farms that were marginal and had failed to yield crops) were a solution to chronic unemployment and water shortages. Government Regulations and Homestay Tourism Rules that enabled villagers to benefit if they rewilded their unproductive farmlands emerged. A talented Nagur-based lawyer-conservationist, Kartik Shukul (Sanctuary Asia 2016b), counsel for the Maharashtra government, worked closely with Sahgal and Mehta to chart a legal pathway to enable local farmers and their heirs to securely retain land ownership. Mehta provided the initial investment capital to construct and manage the high-end homestays so critical to offering villagers a financial option to the near-impossible task of eking out a living from farming on water-starved, biodiversity-depleted soils in an era of climate change.

A staunch supporter of communities, Mehta worked doggedly for more than three years with the originator of the concept, Bittu Sahgal of the Sanctuary Nature Foundation; home-grown conservationist Roheet Karoo, honorary wildlife warden of UPKWS (Sanctuary Asia 2014); and Kailas Hudme, the then Gram Pradhan (village head) of Gothangaon. Together they convinced the local community to register themselves as a cooperative titled the Gothangaon Nisarga Paryatan Sevabhai Sahakari Sansthan in the State of Maharashtra, the first forest conservation–based collective to make rewilding its purpose of existence.

A Real Green New Deal

As a teacher and conservationist for more than four decades, I have introduced hundreds of young people to the magical world of zoology, natural history, and conservation. My personal involvement with the youth of the Gothangaon COCOON Conservancy began from day one but became considerably more cemented when Roheet Karoo introduced me to his team of young men and women in Gothangaon, whom I trained in the theory and practice of natural history.

Figure 4 – Dr. Parvish Pandya points at waterbirds, helping youngsters during the naturalist training program. Far right, Roheet Karoo. Photo by Rahul Maske/Sanctuary Nature Foundation.

Roheet Karoo is truly a gift to tomorrow’s tigers, particularly in the Umred-Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary area. He is currently working to get unproductive farms to forest status by channeling resources to communities whose livelihoods he believes must come from the restored biodiversity on their own lands. The surveys and studies he has undertaken have resulted in better protection strategies. Roheet is the founding secretary of the Wildlife Conservation and Development Centre and honorary wildlife warden of Nagpur district. He has only one dream – to protect tigers and their habitats. His drive, purpose, and single-minded devotion will certainly give the tigers of Umred-Karhandla and Tadoba an extra edge on life.

Figure 5 – The 189-sq.-km (73 sq. mile) expanse of Umred Pauni Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary offers fairly good opportunities to see tigers and other mammals. Photo by Amrut Naik / Sanctuary Nature Foundation.

Quick to learn, and even quicker to teach me about their home, history, and way of life, Roheet’s team of young people are destined to become some of India’s finest nature conservation guides and ethical hospitality professionals. Even more importantly, they are the pioneers who will demonstrate to the people of one of the world’s most densely populated landmasses in the world, that flowing with nature’s tide is not merely an ethical badge of honor but also a survival imperative in an era of climate change. Before my eyes, I see individuals such as Roheet Karoo demonstrating to planners, politicians, and village youth that the quality of life of the Indian subcontinent’s people has everything to do with restoring health to the biodiversity of its ecosystems without which no human aspirations have any hope of success.

The bottom line is that nature has gifted our biosphere the ability to self-repair. Given this truth and given the reality that our planet is in the grip of adverse climate impacts, Sanctuary Nature Foundation’s COCOON Conservancy initiative shines a light on solutions that are both ecologically and economically practical.

Figure 6 – Human-animal conflicts will soon be a thing of past, as COCOON offers additional spaces for biodiversity to flourish and disperse. Photo by Nikhil Tambekar/Sanctuary Nature Foundation.

What is more, the strategy ties in with the advice of those advocating a real global “Green New Deal” that envelopes the conjoined issues of equitable justice and the umbilicus, which connects the dots between climate change, biodiversity, and economics. The Green New Deal is a US congressional resolution that lays out a plan for tackling climate change. Introduced by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Senator Edward J. Markey of Massachusetts, it puts forth a big, bold transformation of the economy to tackle the twin crises of inequality and climate change. In the United States, “from coast to coast, broad local conditions are leading the way in pushing state-level Green New Deal policies that create good jobs, cut climate and local pollution, and counteract racial and economic inequity” (Beachy 2018).

Ultimately, we must find a way to transition from economies built on exploitation and fossil fuels to those driven by sustainable work ethics and clean energy. As Lord Nicholas Stern, chairman of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics, and member of the Governing Board of Sanctuary Nature Foundation, often reminds us: “The economy is a wholly owned subsidiary of the environment.”

PARVISH PANDYA is the director of Science and Conservation and heads the WILD Foundation’s Nature Needs Half project, on behalf of the Sanctuary Nature Foundation in India; email:parvish@sanctuaryasia.com.

References

References

Beachy, B. 2018. The budding movement for a living economy. Sierra Club. Retrieved from https://www.sierraclub.org/compass/2018/09/budding-movement-for-living-economy.Locke, H. 2018. The international movement to protect half the world: Origins, scientific fountions, and policy implications. Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences.

Sanctuary Asia. 2014. Meet Roheet Karoo. Retrieved May 2019 from https://www.sanctuaryasia.com/people/interviews/9748-meet-roheet-karoo-the-man-behind-the-umred-karhandla-wildlife-sanctuary.html.

Sanctuary Asia. 2016a. Umred-Karhandla: An evolving success story… an unknown destiny. Retrieved May 2019 from https://www.sanctuaryasia.com/magazines/conservation/10207-umred-karhandla–an-evolving-success-story-an-unknown-destiny.html.

Sanctuary Asia. 2016b. Meet Kartik Shukul. Retrieved May 2019 from https://www.sanctuaryasia.com/people/interviews/10329-meet-kartik-shukul.html.

Sanctuary Asia. 2018. Meet Sunil Mehta. Retrieved May 2019 from https://www.sanctuaryasia.com/people/interviews/10798-meet-sunil-mehta.html.

Sylven, M. 2011. Nature Needs Half: A new spatial perspective for a healthy planet. International Journal of Wilderness 17(3): 9–11.

Read Next

WILD11 India: Nature-Based Solutions for Life, Livelihoods, and Love

We are pleased to tell you that the 11th World Wilderness Congress (WWC WILD11) will convene in Jaipur, India, in March 2020.

The Historical Meaning of “Outstanding Opportunities for Solitude or a Primitive and Unconfined Type of Recreation” in the Wilderness Act of 1964

The federal land management agencies responsible for wilderness stewardship in the United States play a critical role in fulfilling the Wilderness Act’s mandate to preserve wilderness character.

Jhalana: The Abode of the Urban Leopards

Imagine living in a crowded city of 3.1 million people and learning that amidst this human world, the huge buildings, the maddening crowd, and the deafening sounds lies a small, happy, and peaceful refuge where wild leopards rule.