Habitat improvement efforts have reaped results in Jhalana, India. Here, a mother leopard can be seen roaming with her offspring. photo credit © Abhinav Garg.

Jhalana: The Abode of the Urban Leopards

Stewardship

August 2019 | Volume 25, Number 2

Imagine living in a crowded city of 3.1 million people and learning that amidst this human world, the huge buildings, the maddening crowd, and the deafening sounds lies a small, happy, and peaceful refuge where wild leopards rule. Urban dwellers who have heard of leopards but have rarely come across one would find it difficult to believe that such a place exists within a city’s precincts.

Surprisingly, such a place does exist right within Jaipur, the capital city of the state of Rajasthan in Western India. Spread over 7.7 square miles (19.94 sq. km), the Jhalana Leopard Reserve is home to varied flora and fauna. However, its most famous denizens are its leopards. Over the years, the forest, the leopards, and other biodiversity have withstood the pressure of rapid urbanization and population growth, and excitingly, have thrived here. Having a forest such as this within such a populated city is truly a marvel and a great conservation story (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – A leopard roaming in Jhalana with Jaipur City in the background. Photo courtesy of the Rajasthan Forest Department.

History of Jhalana

Historically, tigers and leopards were common in the hill ranges of Rajasthan, including the Aravali range that is spread across Jaipur known as Jhalana. In the early 19th century, Jhalana was a popular hunting ground with eminent state officials being frequent visitors. The old Shikar Audhi (Hunting Palace) stands as a testament to its popularity (Figure 2). The last tiger was shot in 1948, and its cubs were relocated to the Jaipur Zoo. Since then, leopards have been the apex predator here.

Figure 2 – Shikar Audhi was the hunting palace of royalty and eminent guests. Since the ban on hunting, it has become part of the leopard habitat. Photo courtesy of the Rajasthan Forest Department.

Jhalana extends across the southeastern part of Jaipur. The Aravali ranges run from north to the south of the forest. North of Jhalana is the Amagarh Reserve Forest, which is separated from Jhalana by a busy National Highway (Figure 3). The western and the southern boundary of the Jhalana forest adjoin heavily populated suburbs of Jaipur City, and the eastern boundary has villages and new settlements.

Figure 3 – The Jhalana Forest Reserve with respect to the city of Jaipur. Photo by Dhiraj Kapoor via Google Maps.

Flora

Jhalana is a dry deciduous forest. The trees mostly shed their leaves in the dry season and are a lush emerald during the monsoons. The valley floor’s predominant vegetation is juliflora (Prosopis juliflora) and khejri (Prosopis cineraria). The hardy and rapidly growing juliflora was initially planted to provide firewood for locals. However, this tree does not support the growth of other trees and grasslands. The hill slopes have more native floral variety such as dhonk (Anogeissus pendula), salar (Boswellia serrata), kumta (Acacia senegal), and dhak (Butea monosperma).

Animals and Birds of Jhalana

Even though Jhalana is an isolated and fragmented forest in an urban environment, a variety of faunal life can be found here. The leopard is at the top of the food chain and is an opportunistic predator. Striped hyenas also call Jhalana home (Figure 4). Ungulates such as blue bulls, spotted deer, and some sambar deer are also present. Also seen here are desert foxes, jackals, Indian civets, desert cats, and jungle cats, as are porcupines, jungle rats, monitor lizards, mongooses, and a variety of snakes.

Popular Birding Destination

Jhalana’s improving ecosystem health has been a boon for its resident and migratory avian life. Visitors include the Indian pitta, Asian paradise flycatcher, Eurasian and Indian rollers as well as raptors such as the serpent eagle, sparrow hawk, honey buzzard, and short-toed eagle. Jhalana’s resident birdlife includes owls such as the spotted, scops, and rock-eagle as well as woodpeckers, doves, pigeons, robins, buntings, peacocks, and partridges. The latter two form a major part of the leopards’ diet.

The Advent of Tourism

I began visiting the Jhalana forests in 2004. Until then, like most city dwellers, I had only heard about the elusive leopard – I had never seen one. The visits were occasional and were more about getting away from the chaos of the big city to enjoy the peace and tranquility of the jungle. It was only in 2011, that I had the good fortune of having a brief sighting of the spotted cat. Every visit since then was focused on sighting leopards.

Figure 4 – Although leopards are apex predators at Jhalana, space constraints lead to conflicts with striped hyenas. Photo courtesy of Dhirendra K. Godha.

For the next three years, a small group of individuals formed, all of whom shared an obsession about Jhalana and its leopards. The forest too was gaining in popularity, with images of Jhalana and its leopards appearing frequently on social media platforms. Leopards being nocturnal, elusive, shy, and masters at camouflage generally hide on seeing humans and are not easy to photograph. However, the large number of images being shared by skilled photographers from Jhalana attracted the attention of wildlife enthusiasts, and soon visitor numbers increased dramatically. Tourism is a beneficial tool for conservation if profits are channeled into conservation and carried out in a sustainable manner. Visitors also serve to keep an eye on the management of a park and help to deter potential unsavory elements. However, unregulated tourism can have adverse impacts. In a forest such as Jhalana, located in the midst of an urban area, any disturbance to the wildlife will result in them moving out of their territory and closer to human habitation, which in turn could lead to human-animal conflict. The steady influx of tourists by 2016 caught the attention of the Forest Department of Rajasthan, who had until then simply considered this piece of forestland as part of their inventory. Tourism policies were drafted and rules and regulations established, and for the first time, in March 2016, the Forest Department initiated official safaris in Jhalana. With the advent of regulated tourism, Jhalana became the first and the only forest reserve in India conducting official leopard safaris.

Time for Change

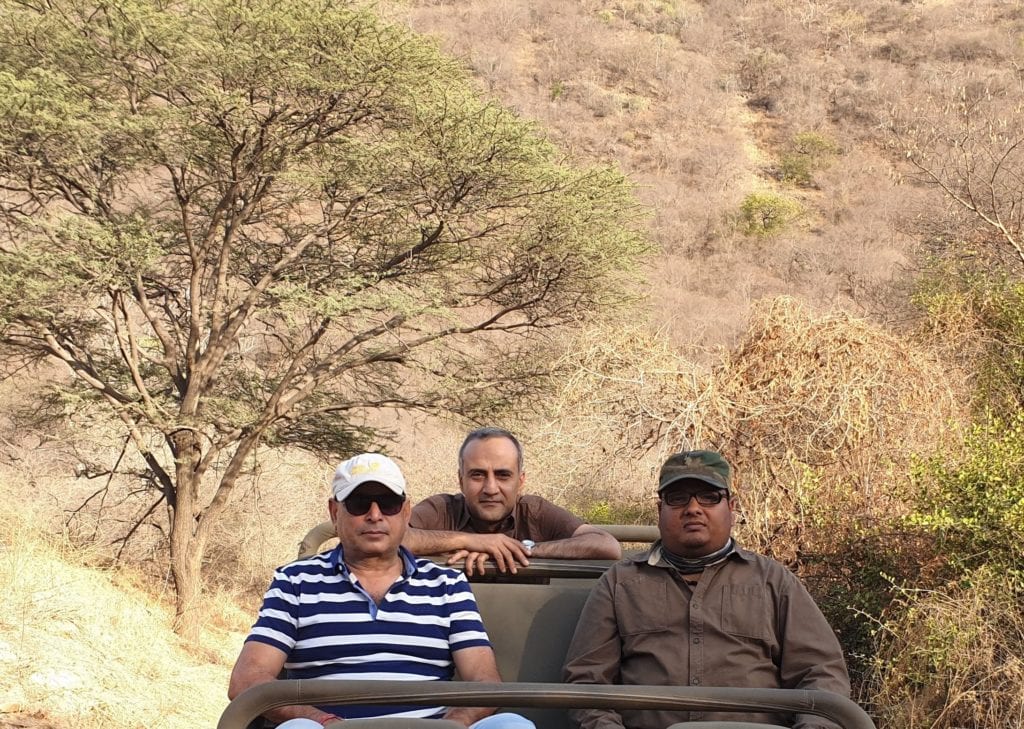

In India, it being a true democracy, nothing changes without the will of the people. In 2017, Gajendra Singh Khimsar, the people’s representative heading the Ministry of Forest in Rajasthan and an avid wildlife enthusiast, expressed keen interest in Jhalana. Apart from forming a committee of dedicated forest officials to undertake the work, he also invited three wildlife enthusiasts, Sunil Mehta, Dhirendra K. Godha, and myself to the committee (Figure 5). Mr. Khimsar deemed that our experience with visiting Jhalana over several years and our knowledge of this unique forest, its flora, and its fauna would be beneficial to Jhalana.

Bringing about change to age-old routines and practices is never easy, but with able leadership, guidance, support, and coordinated teamwork, nothing is impossible. Beginning in 2017, for more than 15 months much effort was taken to get Jhalana on the world wildlife tourism map. Rajasthan by then had become the first state in the country to launch a project to protect leopards by improving their prey base and habitat, thus helping to mitigate human-animal conflict. Jhalana was chosen to be the pilot project and adequate funds were allocated toward various projects to encourage greater wildlife protection.

Figure 6 – The Nature Interpretation Centre at Jhalana visually showcases photographs by local wildlife photographers. Photo by Dhiraj Kapoor

The first step taken was to encourage sustainable tourism in Jhalana. The line between ethical wildlife tourism and uncontrolled, poorly managed tourism is a thin one. Leopards, as mentioned earlier, are shy, and if disturbed they are prone to stray outside their territory. Hence, sustainable tourism initiatives beneficial both for tourists and the wildlife in Jhalana were vital. Toward this end, a set number of symmetrical safari vehicles, especially customized for wildlife tourism, were contracted by the Forest Department, and the maximum number of safari vehicles going inside the park per safari was capped at a maximum of 10 during the morning shift and 10 during the evening shift. The locals were given priority to run these safaris to generate employment, thus making it beneficial for the local economy. Drivers/guides have been trained so that they can provide the best safari experience to guests. The booking process for these safari vehicles was also streamlined by letting guests book 50% of the available seats online. This made it easier for them to plan their visit in advance. Tourist infrastructure that was nonexistent until then was also developed. Waiting rooms, bathrooms, and a café for tourists were constructed. The entry gates were designed in such a way that would allow tourists to truly feel they were escaping the cacophony of the urban world and entering into a wilderness. Our team also helped the Forest Department design and build a Nature Interpretation Centre where guests could learn about the forest and enjoy wildlife photographs taken by regular visitors to the forest (Figure 6). About 25 photographers from Jaipur agreed to display their photographs from Jhalana.

Other Developments

The Jhalana Leopard Reserve’s main challenge has always been the increasing pressures of a growing human population. Over the years, unauthorized constructions and illegal occupation has been slowly eating into the already limited forest area, adding stress to wildlife. Hence it was important to clearly demarcate the boundaries of the reserve to stop any further encroachment and stop all illegal human activities. This herculean task involved the construction of a continuous 8-foot (2.44 m) wall around the 19-mile (30.6 km) periphery of the reserve. The wall acts as the only buffer between the animals and humans and prevents potential human-animal conflicts. It also helps to safeguard the forest from illegal grazing and woodcutting, allowing habitat regeneration.

Wild animals do not need much except for a safe habitat and sufficient prey and water. Although the peripheral wall will go a long way toward providing a safe habitat, much work needs to be done to secure a healthy prey base and water sources. Rajasthan being a dry state has negligible rain, and water is scarce. Hence work on water management has been one of the top priorities. Ponds were dug to harvest and store rainwater for the dry months. This, in turn, also helps in recharging groundwater. During peak summer months when these ponds go dry, a network of pipes lifts water remotely from solar bore wells and fills them up. Water tankers are also used to supply and refill water in the smaller watering holes.

Regular plantation drives are being carried out to plant fruit-bearing and shade-giving trees. Thousands of trees that are native to the region are carefully chosen, planted, and nurtured. Although the survival is low for reasons such as limited water and soil nutrients, the effort is worth it for the few hundred trees that do survive.

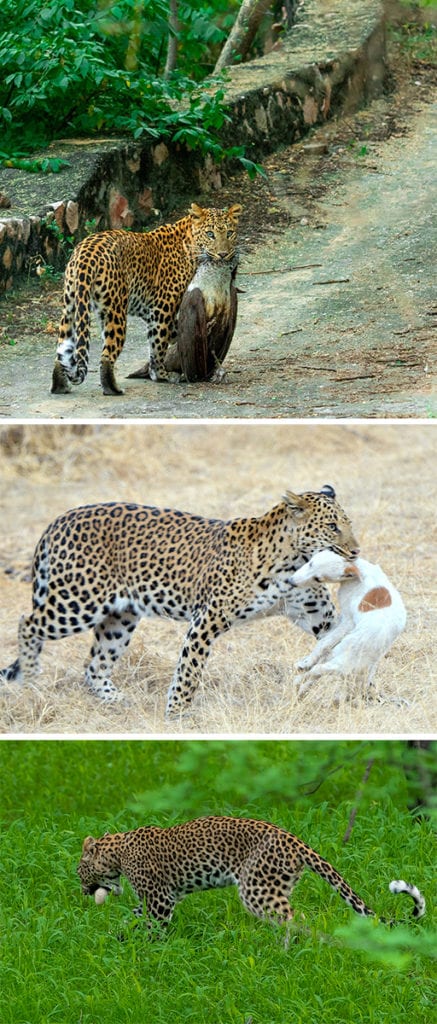

Figure 7a, b and c – In Jhalana, leopards have adapted to a varied diet. Photos by Surendra Chauhan (a, c), and Rahul Jain (b).

A healthy prey base that has adequate food availability is a vital cog in the wheel for a forest. The Jhalana leopard has a small build compared to leopards in other parts of the country, and is perhaps the reason why adult blue bulls, or nilgai (antelope), abundant in the forest are not its preferred prey. Without this natural check, antelopes overgraze, thus diminishing food resources for other herbivores such as chital, also known as spotted deer. Since the chital population is on the decline in Jhalana, leopards have adapted to kill and survive on smaller prey such as peacocks, monkeys, partridges, and squirrels. They have also been recorded eating peahen eggs, monitor lizards, and occasionally making dog and pig kills in the forest peripheries (Figures 7a, b, and c).

Due to this skewed predator-prey ratio, the Forest Department has undertaken the huge task of clearing areas infested with the invasive Juliflora trees and instead developing grasslands to increase the spotted deer population here. Once the habitat is improved, the Forest Department can also consider introducing chital.

Effective monitoring is essential for the success of any conservation effort. To ensure that Jhalana is on the world tourism map, it was also imperative to introduce the best scientific monitoring practices. Camera traps were introduced to remotely study the animals. State-of-the-art high-definition as well as thermal cameras were installed to cover the entire 7.7 sq. miles (19.94 sq. km) of Jhalana forest. This was the best way to red-flag any unauthorized movement. New patrolling routes were also opened to ensure better patrolling of the forest on foot. Other significant steps included removing high-tension electricity cables, using solar power to draw water, introducing battery-operated safari vehicles, opening new safari routes, and dismantling human-made structures.

Identification of Leopards

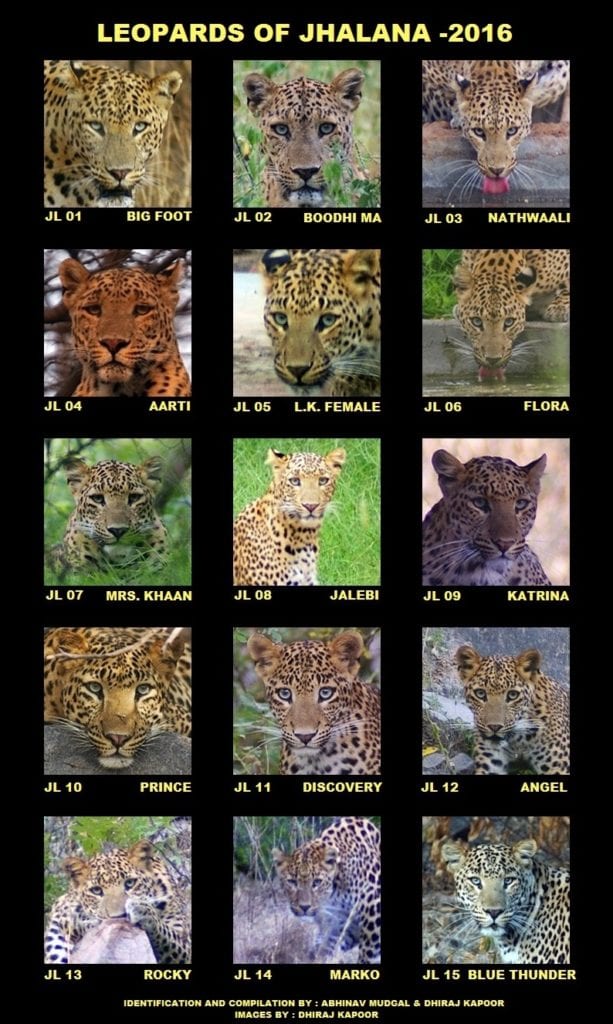

Figure 8 – The first published identification of the leopards of Jhalana by Abhinav Mudgal and Dhiraj Kapoor.

It is difficult to distinguish individual leopards simply on the basis of their size and area of movement. To get an approximate count of leopards in the forest it was necessary to scrutinize photographs and identify individual leopards on the basis of their rosettes. Rosette patterns on each leopard are like the fingerprint patterns of humans. No two leopards have the same rosette pattern. I had been photographing Jhalana’s leopards since 2014. Along with another avid wildlife enthusiast and brilliant photographer Abhinav Mudgal, who has also been visiting Jhalana for several years, we began the overwhelming task of analyzing the thousands of leopard images that we had in our data to segregate them on the basis of rosette patterns.

After several months of close scrutiny, 16 individual leopards were identified. These leopards were given individual identification numbers and names according to their unique features or on the basis of the territory they roamed. This research was presented to the Forest Department in 2016 and was the first document prepared on the leopards of Jhalana. The identification has helped the Forest Department better monitor the movement of these leopards (Figure 8). By 2019, the list was further updated and confirmed the presence of 47 leopards in Jhalana.

By 2019, an extensive report was produced on the flora and fauna of Jhalana and its leopard movements. Unique leopard behavior typical to Jhalana was observed during the study. Leopards are deemed to be solitary animals, but in Jhalana, due to space and resource constraints, leopards were witnessed forming prides. For example, an adult female was seen with young cubs from her current litter along with adult cubs from her previous litter, contrasting with the typical solitary nature of the species.

The report and observations were presented to the provincial Forest Department. Also presented were the challenges that Jhalana faces, and recommendations to further improve and protect the habitat. Several recommendations were

- Developing grasslands and planting trees (other than Juliflora) has to be carried out on a permanent basis. Grasslands are essential if the prey density is to be increased.

- Radio collaring of two leopards, one dominant male and one subadult male to track and study their movement and also to determine the pressures they are facing in Jhalana.

- Developing safe and secure migration routes with the adjoining Amagarh Forest.

- With the increase in the leopard population, paying special attention to increasing prey density.

Future and Challenges

In just over a year, under Project Leopard, Jhalana has transformed from a nondescript piece of forestland into a leopard tourism reserve. Despite the many challenges of being located in an urban area, several positive initiatives have allowed the flora and fauna of this reserve to improve. One challenge that still needs to be overcome is the lack of secure connectivity to other forest pockets in the vicinity. The Amagarh forest is separated from Jhalana by a six-lane National Highway, which is a death trap for migrating animals. Leopard fatalities due to road accidents have been reported. It’s essential for a secure corridor to be established between these two forests both to prevent such deaths and to help in diversifying the already diminishing gene pool that has resulted from inbreeding.

Although efforts are being made to increase the prey base, more needs to be done. Given the thriving leopard population and the lack of sufficient pastures for herbivore prey, the overall prey base seems to be on the downward trend. This may eventually help in the weakest being eliminated, but it also leads to leopards moving out of the jungle and into human habitation in search of food (Figure 9).

Figure 9 – Instances occur where leopards move into adjoining colonies. While not very common, this phenomenon will only increase if the natural habitat of Jhalana is not protected. Photo courtesy of Dinesh Dabi.

Jhalana was under the Territorial Wing of the Rajasthan Forest Department until it was identified as a Leopard Reserve in 2017 and transferred to the department’s Wildlife Wing. Under this process, senior forest officials such as DCF Sudarshan Sharma and Range Officer Janeshwar Singh, who had years of experience in managing wildlife parks in Rajasthan, were transferred to Jhalana. This has brought in much-needed expertise at the top level. However, more expertise and training is required for staff who undertake foot patrolling and monitoring. A team of dedicated and trained forest guards must be deployed in Jhalana as soon as possible.

Ultimately, forests cannot survive unless there is local support. Greater awareness must be created about the benefits of undisturbed green spaces and sustainable tourism. Periphery dwellers in particular must be involved in the conservation process and be sensitized toward wild animals. Proper procedures should also be in place in case of wild-animal straying incidents, including evacuations to avoid human-animal conflict.

The Jhalana Leopard Reserve is the only reserve in the country dedicated to leopards. It is today a jewel in the crown of the erstwhile princely state of Jaipur. This forest reserve is one of the finest examples of successful human-animal cohabitation stories in the world.

DHIRAJ KAPOOR has been visiting Jhalana since 2004. Along with his team and the Forest Department, he has been working on several projects focused on habitat improvement in Jhalana. The author was one of the pioneers in identifying the individual leopards of Jhalana; email: dhirajkapoor@yahoo.com.

Read Next

WILD11 India: Nature-Based Solutions for Life, Livelihoods, and Love

We are pleased to tell you that the 11th World Wilderness Congress (WWC WILD11) will convene in Jaipur, India, in March 2020.

The Historical Meaning of “Outstanding Opportunities for Solitude or a Primitive and Unconfined Type of Recreation” in the Wilderness Act of 1964

The federal land management agencies responsible for wilderness stewardship in the United States play a critical role in fulfilling the Wilderness Act’s mandate to preserve wilderness character.

Informing Planning and Management Through Visitor Experiences in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

Managing recreational opportunities and resource use while simultaneously working to conserve unique ecosystems for future use is particularly challenging in a vast and varied landscape such as Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.