Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. photo credit © Jeff Marion

Informing Planning and Management Through Visitor Experiences in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

Science & Research

August 2019 | Volume 25, Number 2

PEER REVIEWED

ABSTRACT Policies mandate that managers at Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument must balance recreational opportunities with a variety of resource management and utilization activities across a vast and diverse landscape containing numerous Wilderness Study Areas and other lands containing spectacular resources. This balancing act is stressed by increasing levels of use and recent changes in management direction and policy. An understanding of visitor preferences and current social conditions is an essential component of recreation management; however, scant social science data exist for the Monument. This study used semistructured qualitative interviews to describe Monument visitors’ motivations, experiences, and perceptions to determine existing social conditions. Results can help inform possible indicators of quality that can be used for long-term monitoring and adaptive management of the Monument’s unique wilderness resource.

Managing recreational opportunities and resource use while simultaneously working to conserve unique ecosystems for future use is particularly challenging in a vast and varied landscape such as Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (GSENM), a federal protected area in south-central Utah managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). This challenge is confounded by increased recreational use within the state of Utah and the protected areas that surround GSENM, which is thought to be correlated with a marked increase in state tourism promotional strategies (e.g., “The Mighty Five”; “Utah – Life Elevated”; Smith, Wilkins, Gayle, and Lamborn 2018). The increased use may be amplified in GSENM specifically due to recent federal policy directives that reduced the size of the original proclamation establishing the Monument (Presidential Proclamation 9682) (BLM 2000). Inevitably, recreational use leads to varying levels of resource impacts (Hammitt, Cole, and Monz 2015). The limited social science research that has been conducted by external focus groups in GSENM suggests that visitors seek naturalness and tranquility in the remote and rugged landscape, which promotes self-reliance and discovery (Casey 2014). However, these characteristics are in jeopardy due to the increased use of the area, and the associated impacts to the resources, such as vandalism, trash, vegetation trampling, and crowding (Casey 2014).

Policies mandate that managers at Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument must balance recreational opportunities with a variety of resource management and utilization activities across a vast and diverse landscape containing numerous Wilderness Study Areas and other lands containing spectacular resources.

At a national and state level, the BLM has developed strategic plans to inform management approaches that intend to mitigate ecological and social impacts (e.g., BLM 2007; 2011; 2014). These plans describe how GSENM is charged with providing “sustainable recreation” opportunities, and those that “provide for environmental sustainability while fulfilling the social and economic needs of present and future generations” (BLM 2011, p. 23). Furthermore, the 15-year strategy, as prescribed in the BLM’s “Geography of Hope” (2011), states that the agency must use science to aid in managing for conservation, providing for compatible uses that protect the resources and values of GSENM. Finally, GSENM must “identify research needs and incorporate physical, biological, and social science(s)” to inform adaptive management, interpretation and outreach (Theme 1; Goal 1c, p. 9, BLM [2011]). This strategy specifically suggests that the agency “conduct periodic visitor surveys” to examine the experiential qualities of their needs (Theme 2; Goal 2d, p. 14) through the application of science to inform interpretive strategies and support programs such as “Leave No Trace to foster outdoor ethics and stewardship” (Theme 3; Goal 3d, p. 17).

These planning documents point to the need for appropriate monitoring protocols, which require understanding of suitable social and ecological indicators that can be reviewed and adaptively managed using frameworks such as those proposed by the Interagency Visitor Use Management Framework (see: https://visitorusemanagement.nps.gov/VUM/Framework, accessed May 2, 2019). Despite these robust management directives, science regarding the human dimensions of use and experience in GSENM is scant. Without adequate data, managers cannot make informed management decisions, nor appropriately monitor conditions for changes over time.

Study Purpose

The purpose of this study was to collect information from GSENM visitors about their recreational experiences and perceptions of social and ecological conditions to inform management of desired visitor experiences and current conditions. An associated outcome of this research was to develop potential indicators of quality regarding desired visitor experiences (Cahill, Collins, McPartland, Pitt, and Verbos 2018; Carlson, Cole, Finnan, Hood, and Weis, 2010; Manning 2012; Verbos, Vdala, Mali, and Cahill 2017) that could be monitored and adaptively managed.

Methods

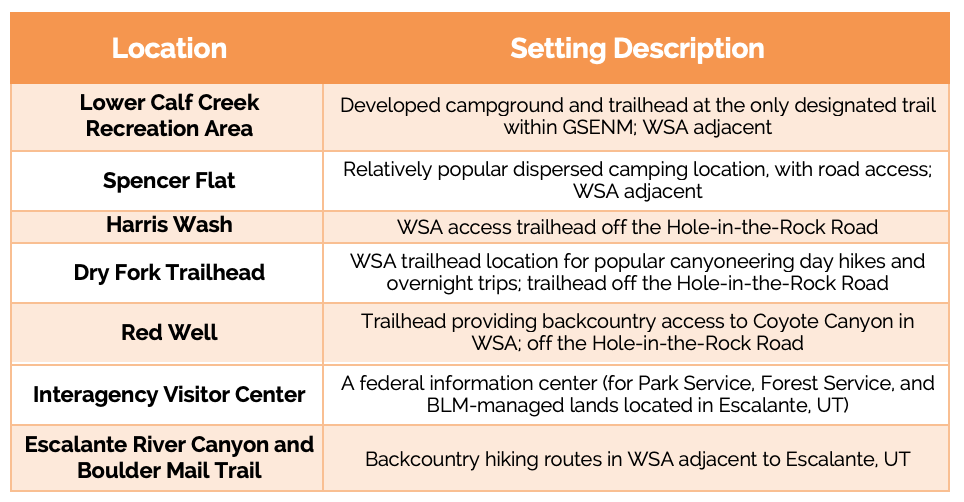

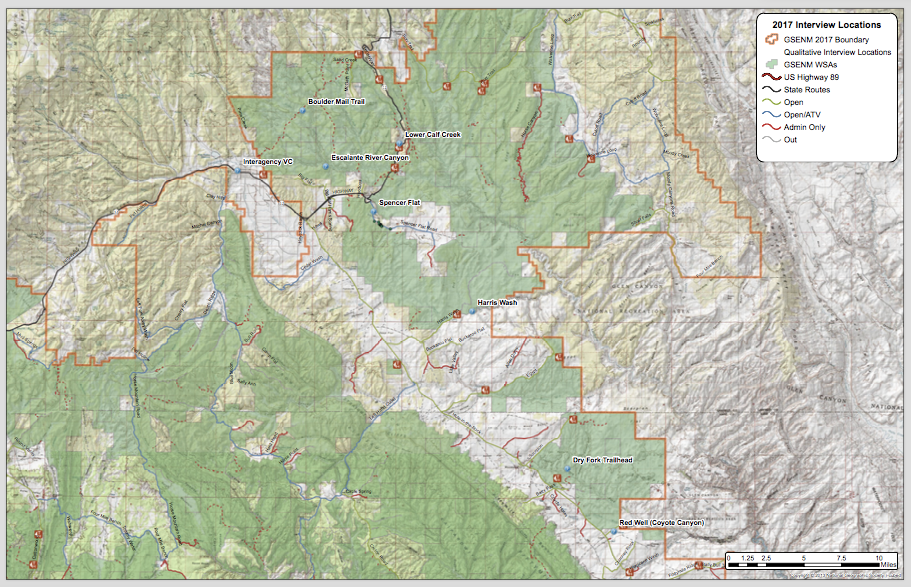

Given the limited understanding of visitor use and in-situ visitor experiences in GSENM (Casey 2014), a qualitative, on-site semi-structured interview approach was used to assess visitor perceptions and experiences of GSENM. To represent the variety of user-groups across the vast and varied GSENM landscape, potential study participants were intercepted at multiple locations in the Monument during September and October 2017 (Table 1 and Figure 1). In consultation with GSENM, these locations were selected to include the unique landscape features that attract varied types of users (e.g., Wilderness Study Areas [WSA], backcountry, frontcountry/roadside) in areas of moderate to high volumes of use.

To help inform management of desired visitor experiences, current conditions, and possible visitor experience indicators, the semistructured interview focused on visitor demographics, travel patterns, motivations and expectations, perceptions of their experiences as related to current social and ecological conditions within GSENM, and self-reported awareness and attitudes toward wilderness and low impact practices. Some interviews were conducted with more than one visitor. All interviews were digitally recorded, and the methodology and associated semi-structured interview script were evaluated and approved by the Federal Office of Management and Budget as well as the researchers’ Institutional Review Board.

Inductive open coding was used to gain an understanding of patterns and salient topical areas (Saldaña 2016). All interviews were transcribed and coded in accordance with the developed code book, and coding checks were completed by two additional researchers. Ultimately, salient themes emerged (Lincoln and Guba 1985) and key quotes were selected to highlight the constructs that were revealed. Coded interview responses informed development of visitor experience themes and potential indicators of quality for visitor use and experience. In total, 58 respondents provided their input through 40 interviews in GSENM with a response rate of 91%. Interviews ranged from approximately 8 to 25 minutes.

Results

Respondent Characteristics

The age of respondents ranged from 22–76, with an average age of 54. Most respondents noted that this was their first trip to GSENM, while others had visited the area numerous times. Length of stay varied considerably by respondent; several respondents had been in GSENM for three or more days, while others were only there for the day. When respondents were asked to describe their primary destination within GSENM, responses were mixed, with some seeking specific locations within the Monument and others seeking to experience GSENM as a whole. Common locations were the Hole-in-the-Rock Road, Peekaboo, Spooky and Zebra slot canyons, Calf Creek, Death Hollow, and Coyote Gulch.

Primary Activities

The primary activities mentioned by respondents varied by the location where respondents were intercepted, and ranged from car camping to day hiking to backpacking. Hiking, mentioned by all respondents, was the most prevalent activity. The other frequently mentioned activity was scenic driving in GSENM and the surrounding areas. Less frequently mentioned activities included mountain biking and hunting.

Pleasant Discovery and Displacement from Other Protected Areas

Most respondents were not solely visiting GSENM, often mentioning their visits to Zion and Bryce Canyon, popular national parks within two hour’s drive of GSENM. For several respondents, their visit to GSENM was not necessarily intended but rather a pleasant surprise while touring other protected areas in the region. Some respondents indicated that their visit was motivated by recent modifications of GSENM boundaries, while others sought refuge in GSENM to escape crowding in the more popular national parks in the region.

“The stop at the campsite was completely accidental. We were supposed to just drive through, but we stopped.” #2

“We didn’t really have any expectations… We were going to go a different way to get to Moab and then I saw this hike… So we re-routed our car.” #5

“I was like ‘Wait, Grand Staircase looks really cool, let’s stop there.” #23

“We thought about going to Bryce and Zion, but with everything politically that’s happening, we decided we wanted to come here.” #4

“It [GSENM] might be going away. That was part of it.” #39

“We’re avoiding Bryce and Zion.” #1

Potential Displacement within the Monument

Respondents were asked if there were any specific reasons why they were unable to visit areas they had planned or hoped to experience in GSENM. To reduce bias, the question purposely avoided asking about crowding or other social conditions. Responses varied considerably, from lacking a proper vehicle and related weather conditions, to aspects related to temporal planning and displacement associated with perceptions of crowding. In general, respondents mentioned the remote and occasionally challenging resource conditions, and they noted the number of other visitors encountered was acceptable and manageable if planned for in advance.

“I think that’s something we’ve kind of missed out a little bit. Not having the ability to go on those 4×4 road routes.” #1

“Conditions haven’t really allowed me to go to everything I was hoping to go to… the rain filled this canyon with water.” #11

“We get in early…. If you get in early enough… you get in and fight the crowds on the way back out.” #21

“You just can’t do mainstream stuff anymore at mainstream times.” #33

Crowding Compared to Other Protected Areas

Many respondents noted the lack of other visitors compared to other parks and protected areas they had experienced, and all perceived this as a benefit for their experience.

“We saw very few people, even here you see people [Lower Calf Creek] but it’s not crowded. It’s not like a year and a half ago when we went to Arches.” #4

“Staircase is not overcrowded. Zion in the afternoon got overcrowded. Bryce tended to get there also. But down here? No, we haven’t experienced any of that.” #12

“For me it’s just about…. Being out in nature without a ton of people around. Like, Arches is beautiful but there are so many people around.” #26

“What I have noticed is that you don’t have huge crowds out here and it’s just beautiful out here…. Something that we enjoy about Escalante…. Zion is beautiful but there’s a million people and that gets kind of boring. #24

“[Lack of crowds] in staircase? Yeah. There were some hikes up in Bryce and Canyonlands that were just crazy…. Just tons of people…. You’re not alone, you’re just surrounded by tons of people.” #25

“You know, you see people, but it’s not overcrowded…. And so, if you want to take the time you can really just get away and be by yourself.” #27

Wilderness Experiences

Given the abundant opportunities to experience WSAs within GSENM, respondents were specifically asked to describe how experiencing a sense of wilderness fit into their reasons for visiting. The majority of respondents noted that they were able to experience their personal definition of a wilderness experience while in GSENM. Several respondents described their experience using words that align with specific wilderness character qualities including “natural features” and “opportunities for solitude and/or primitive and unconfined recreation” (Cordell, Bergstrom and Bowker 2005; Landres 2013; Landres, Vagias, and Stutzman 2012). However, respondents were largely unaware of whether they had specifically been in a designated wilderness area or WSA.

“I think we live in a beautiful area, but like she said, it’s just so full of people on the weekends. Wilderness, for me, is about going somewhere where there aren’t very many people. And this is an easy place to do that…. And you’re the first people we’ve seen. It’s been great. I think there’s definitely an appreciation for the land…. But some of that has been lost that I think has been preserved here.” #7

[Wilderness experience….] “It’s why we came out here.” #23

“That’s what I’m looking for. We need to get out there and it’s just peaceful. I mean, it’s just spiritual for us to get out here. Trying to find some solitude is big for us. I love to just be out here, where you just feel like you’re just out here by yourselves.” #28

“I like the remoteness of it… It looks like there is nothing out here when there is everything out here.” #32

“Oh, yeah, it’s the whole reason that I come out here. I’ve been able to experience low usage trails and that’s very important to me.” #34

“Obviously, coming from the UK, we don’t really have much wilderness anymore. There’s so many of us that we don’t have many of these amazing vistas and soft sheer…. You have to really engage in it and be aware. To experience that is a lot of fun.” #2

Figure 2 – Example of scenery and opportunity to experience solitude in GSENM. Photo by Jeff Marion.

A number of notable aspects of the GSENM experience emerged regarding common motivations and experiences sought by respondents in this study. Respondents expressed concepts commonly noted when recreating in wilderness (Cole 2012; Hall 2001; Taff, Weinzimmer, and Newman 2015; Watson et al. 2007) and included seeking, experiencing and enjoying nature, natural quiet, and escape through solitude.

“We decided this was the most beautiful hike we’ve been on.” #5

“Great natural features…” #6

“To see the landscape that is unusually beautiful and preserved, and that is what I am finding…. “The areas where there [are] no sights of people, sounds of people, just at times pure quiet. You don’t get that very often.” #9

“The mountains – the colors just… we don’t see that in Washington.” #14

“[This is a] nice place to camp where you don’t have people running generators.” #27

“It’s so quiet here.” #29

“Quiet, natural quiet is a big deal.” #33

“Just getting away. Beautiful spot and going to a spot where people are not likely to be.” #6

“Beautiful place and a lot calmer than where we live.” #7

“We’re always looking for places to go. You know, just be out in nature, be away from it all.” #21

“When you go to the wilderness, it refreshes you completely.” #26

“I love the solitude here. Like I say, you can see cars drive by, but with a little effort you can be alone here…. It’s nice being here, getting up in the morning and being pretty much the only guy in at least a half mile, and you get to sit and watch the sun hit the hills. It’s a pretty good life.” #27

Features That Negatively Impacted Visitor Experiences

While the majority of respondents noted being extremely pleased with their experiences in GSENM, we asked about a number of potentially negative aspects that may have impacted visitor experiences. For example, respondents were asked about the behaviors of other visitors, and the conditions of the natural resources in GSENM. Regarding the behaviors of other visitors, respondents described the following:

“I got a little irritated a little bit last night when I smelled smoke from my neighbor’s fire [while backpacking in the Death Hollow area, where fires were banned].” #3

“We definitely got lost because of some stupid cairns… I mean, these cairn freaks are everywhere, building rock piles and misleading people.” #23

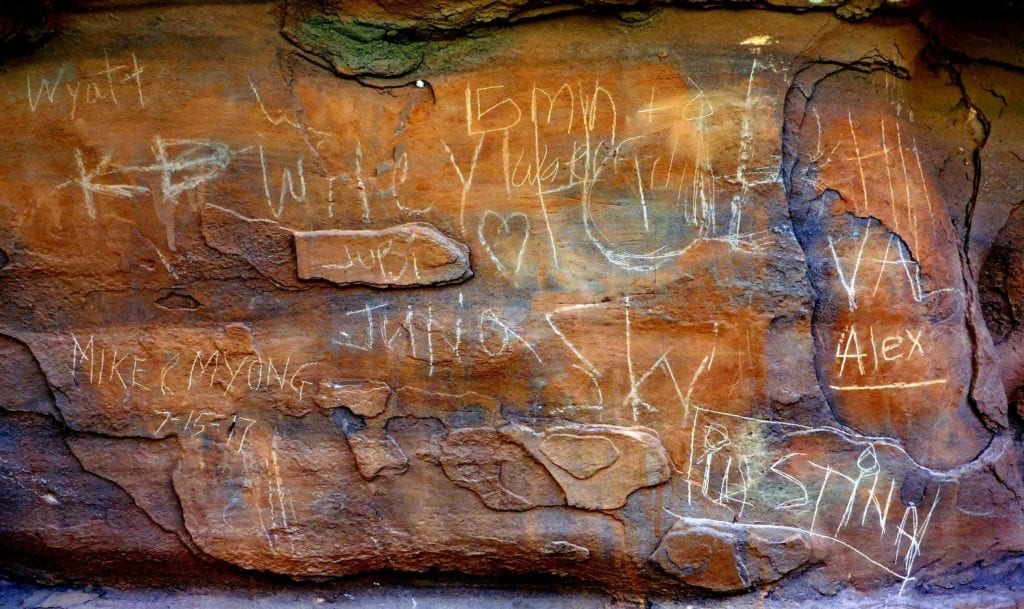

Figure 3 – Example of avoidable impacts caused by depreciative behaviors in GSENM. Photo by Jeff Marion.

“I saw someone with a dog off the leash and I love dogs, and I wish I had my dog with me, but I was like ‘that’s not supposed to…’ you know? It’s just frustrating when you have to abide by the rules and other people don’t. #36

“Graffiti, which is disappointing.” #4

“There was one firepit.” #7

“I found some trash on the trail…. I saw a tire and a plastic tarp.” #9

“It’s just the trash thing. Really, that pisses me off. And the graffiti. They are vandalizing the petroglyphs and that kind of stuff…. Everybody has chosen these walls to scratch their names into and everything. And that’s kind of a bummer.” #29

Perceptions of Low Impact Practices

Given the BLM’s commitment to promoting Leave No Trace practices (BLM 2011), researchers specifically asked respondents to describe their awareness and general attitudes toward low impact practices. Responses varied considerably, but most respondents appropriately described specific behaviors related to minimizing impacts.

“That stuff is like take your trash out with you, try to stay on the trails. Impacts to ecology around the trails and that sort of stuff. Don’t deface the monuments.” #13

“I’m a certified Leave No Trace trainer.” #14

“Of course, pack it in, pack it out.” #16

“Step on rock or sand, don’t step on vegetation.” #37

“Don’t remove anything from artifacts or anything. And also, don’t leave garbage.” #48

Discussion and Implications

Several notable findings emerged that can be used to inform management of desired visitor experiences, conditions respondents experienced, and possible visitor experience indicators of quality. It is notable that for many visitors, GSENM may not be their primary destination but rather a pleasant surprise (due to the natural beauty and opportunities for solitude) during explorations of adjacent popular protected areas in the region. The majority of respondents noted the benefits of experiencing the less crowded environment of GSENM compared to other protected areas they had experienced. A few respondents noted the high density of other visitors in certain GSENM areas, such as Lower Calf Creek, Peek-A-Boo, and Spooky Gulch canyons. However, if mentioned, many respondents indicated that they expected to experience higher levels of crowding in those areas, and that planning ahead to visit during less popular times of the day might have mitigated this issue.

Respondents were largely unaware of whether they had specifically been in a wilderness area or WSA during their visit to GSENM, despite the fact that many of the respondents were intercepted and interviewed while in designated WSAs. The majority of respondents noted that they were able to experience their personal definition of a wilderness experience while in GSENM. Resulting statements often described concepts that align with character qualities including “outstanding natural features,” and “opportunities for solitude and/or primitive and unconfined recreation” (Cordell et al. 2005; Landres 2013; Landres et al. 2012), and these were important reasons visitors sought or unexpectedly enjoyed experiences in GSENM. For those who specifically sought desired experiences in GSENM, common motivations also aligned with wilderness character qualities, and included seeking, experiencing and enjoying nature, natural quiet, and escape through solitude.

Overall, very few respondents noted elements that negatively impacted their visitor experience. The majority of respondents indicated that they were extremely pleased with their experiences in GSENM. However, the behaviors of other visitors, such as illegal fires in the backcountry, excessive and misleading cairns, dogs off leash, and crowding in some areas were mentioned by a few respondents. Furthermore, the condition of natural resources in GSENM, as it related to depreciative behaviors of other visitors was often mentioned. For example, several respondents noted their experience in GSENM was negatively affected by avoidable impacts caused by others, such as litter, graffiti, and damage to petroglyphs (Blenderman, Taff, Wimpey, Marion, and Schwartz 2018).

Conclusions and Suggestions

Results indicate that many of the visitors to GSENM may not have substantive expectations for the area. Thus, management has the opportunity to shape visitor expectations and associated behaviors in a manner that aligns with management objectives for the area (Cole 2004; McCool 2006; Verbos et al. 2017). For example, if management wants to promote certain areas and decrease use in other more heavily trafficked locations, they might consider proactively working with state and local tourism entities to develop appropriate messaging. Awareness of and attitudes toward low impact practices largely aligned with recommended Leave No Trace practices, but if use continues to increase, GSENM staff could enhance their promotion of low impact behaviors through a variety of dissemination strategies (Marion and Reid 2007). Specific messaging around the importance of low impact practices for maintaining wilderness character could be beneficial, and it may also aid in creating understanding and awareness of the designated WSAs within GSENM (Taff et al. 2015; Vagias and Powell 2010).

The results of these interviews suggest that some people are motivated to experience GSENM for the wilderness character qualities they can find in this vast and unique landscape, despite not readily recognizing that they might be in or have traveled through wilderness. Possible indicators for future monitoring include perceived level of crowding and use densities, levels of anthropogenic sounds, and the level of human-caused impacts to natural and cultural resources (Cahill et al. 2018; Verbos et al. 2017; Watson et al. 2007)

Limitations and Future Research

This study used qualitive methodologies and sampled a limited number of visitors over a relatively short period of time in several key areas within the vast landscape encompassed within GSENM. Future research may consider quantifying suggested indicators of quality in these and other areas of the Monument, and potentially consider sampling during other times of year that might experience different visitor use patterns. Further quantifying these potential indicators and defining possible thresholds would aid long-term monitoring efforts and related adaptive management. Finally, pairing visitor perceptions with actual resource conditions (e.g., trail, campsite, etc.) would improve understanding of the association between the social and ecological system and provide an empirical basis for managers to adaptively manage GSENM.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff of GSENM and the National Conservation Lands system for their guidance and support of this research. Specifically, we appreciate the support this research received from Jabe Beal and Phadrea Ponds.

B. DERRICK TAFF is an assistant professor in the Recreation, Park and Tourism Management Department at Penn State University; email: Bdt3@psu.edu.

JEREMY WIMPEY is the owner of Applied Trails Research, an outdoor recreation firm that develops science-based solutions to challenging visitor use management issues; email: jeremyw@appliedtrailsresearch.com.

JEFFREY L. MARION is a recreation ecologist with the US Geological Survey stationed at Virginia Tech; email: jmarion@vt.edu.

JOHANNA ARREDONDO is a doctoral student at Virginia Tech, Forest Resources & Environmental Conservation; email: johanna.arredondo@gmail.com.

FLETCHER MEADEMA is a doctoral student at Virginia Tech, Forest Resources & Environmental Conser-vation; email: fmeadema@vt.edu.

FORREST SCHWARTZ is a faculty member in the Adventure Education Department at Prescott College; email: forrest.schwartz@prescott.edu.

BEN LAWHON, MS, joined the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics staff in 2001, where he serves as the education director. His current responsibilities include research, curriculum development, management of national education and training programs, agency relations, and oversight of national outreach efforts; email; ben@lnt.org.

CODY DEMS is a master’s student in the Department of Ecosystem Science and Management at Penn State University; email: cld403@psu.edu.

References

References

Blenderman, A., B. D. Taff., J. Wimpey, J. Marion, and F. Schwartz. 2018. Understanding and mitigating wilderness therapy impacts: The Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument case study. International Journal of Wilderness 24(2): 18–29.

Bureau of Land Management. 2000. Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Management Plan. BLM report: BLM/UT/PT-099/020+1610.

———. 2007. National Landscape Conservation System Science Strategy. BLM Report: BLM/WO/GI-06/027+6100. Retrieved May 2, 2019, from https://www.blm.gov/sites/blm.gov/files/uploads/NLCS_ScienceStrategy.pdf.

———. 2011. National Landscape Conservation System 15-year Strategy 2010–2025: The Geography of Hope. BLM Report: BLM/WO/GI-11/013+6100. Retrieved May 2, 2019, from https://www.blm.gov/wo/st/en/info/newsroom/2011/September/NR_09_30_2011.html.

———. 2014. National Conservation Lands: Bureau of Land Management – Utah, 5-Year Strategy (2014–2019). Utah State Office. Retrieved May 2, 2019, from https://www.blm.gov/download/file/fid/3815.

Cahill, K., R. Collins, S. McPartland, A. Pitt, and R. Verbos. 2018. Overview of the interagency visitor use management framework and the uses of social science in its implementation in the National Park Service. The George Wright Forum 35(1): 32–41.

Carlson, T. D. D. Cole, K. Finnan, K. Hood, and J. Weis. 2010. Ensuring Outstanding Opportunities for Quality Wilderness Visitor Experiences: Problems and Recommendations. Retrieved from https://www.wilderness.net/NWPS/documents/FS/Outstanding%20Opportunities%20for%20Visitor%20Experiences_WAG_Report.pdf.

Casey, T. 2014. Recreation Experience Baseline Study Report for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Executive Summary. Report published by the Natural Resource Center at Colorado Mesa University, Grand Junction.

Cole, D. N. 2004. Wilderness experiences: What should we be managing for? International Journal of Wilderness 10(3): 25–27.

———. 2012. Wilderness visitor experiences: A selective review of 50 years of research. Park Science 28(3): 66–70.

Cordell, K. H., J. C. Bergstrom, and J. M. Bowker. 2005. The Multiple Values of Wilderness. State College, PA: Venture Publishing.

Hall, T. E. 2001. Hikers’ perspectives on solitude and wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 7(2): 20–24.

Hammitt, W. E., D. N. Cole, and C. A. Monz. 2015. Wildland Recreation. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Landres, N. 2013. Commonality in wilderness character: A personal reflection. International Journal of Wilderness 19(3): 14–17.

Landres, P., W. M. Vagias, and S. Stutzman. 2012. Using wilderness character to improve wilderness stewardship. Park Science 28(3): 44-48.

Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Manning, R. 2012. Frameworks for defining and managing the wilderness experience. In Wilderness Visitor Experiences: Progress in Research Management, ed. D. Cole. Missoula, MT. RMRS-P-66.

Marion, J. L., and S. E. Reid. 2007. Minimising Visitor Impacts to Protected Areas: The Efficacy of Low Impact Education Programmes. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 15(1): 5–27.

McCool, S. F. 2006. Managing for visitor experiences in protected areas: Promising opportunities and fundamental challenges. Parks: The Visitor Experience Challenge 16(2) 3–9.

Presidential Proclamation 9682. 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2019, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/presidential-proclamation-modifying-grand-staircase-escalante-national-monument/.

Saldaña, J. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

Smith, J. W., E. Wilkins, R. Gayle, and C. C. Lamborn. 2018. Climate and visitation to Utah’s ‘Mighty 5’ national parks. Tourism Geographies 20(2): 250–272.

Taff, B. D., D. Weinzimmer, and P. Newman. 2015. Mountaineers’ wilderness experience in Denali National Park and Preserve. International Journal of Wilderness 21(2): 7–15.

Vagias, W. M., and R. B. Powell. 2010. Backcountry visitors Leave No Trace attitudes. International Journal of Wilderness, 16(3): 21–27.

Verbos, R., C. Vdala, P. Mali, and K. Cahill. 2017. The Visitor Use Management Framework: Application to wild and scenic rivers. International Journal of Wilderness 23(2): 10–15.

Watson, A., B. Glaspell, N. Christensen, P. Lachapelle, V. Sahanatien, and F. Gertsch. 2007. Giving voice to wildlands visitors: Selecting indicators to protect and sustain experiences in the Eastern Arctic of Nunavut. Environmental Management 40: 880–888.

Read Next

WILD11 India: Nature-Based Solutions for Life, Livelihoods, and Love

We are pleased to tell you that the 11th World Wilderness Congress (WWC WILD11) will convene in Jaipur, India, in March 2020.

The Historical Meaning of “Outstanding Opportunities for Solitude or a Primitive and Unconfined Type of Recreation” in the Wilderness Act of 1964

The federal land management agencies responsible for wilderness stewardship in the United States play a critical role in fulfilling the Wilderness Act’s mandate to preserve wilderness character.

Jhalana: The Abode of the Urban Leopards

Imagine living in a crowded city of 3.1 million people and learning that amidst this human world, the huge buildings, the maddening crowd, and the deafening sounds lies a small, happy, and peaceful refuge where wild leopards rule.