photo credit © Kevin Crosby

The Historical Meaning of “Outstanding Opportunities for Solitude or a Primitive and Unconfined Type of Recreation” in the Wilderness Act of 1964

Soul of the Wilderness

August 2019 | Volume 25, Number 2

The federal land management agencies responsible for wilderness stewardship in the United States play a critical role in fulfilling the Wilderness Act’s mandate to preserve wilderness character. Wilderness character, as currently understood (Landres et al. 2015), is composed of distinct and interrelated “qualities” that are meant to connect the statutory language of the law to stewardship activities and on-the-ground conditions (Dvorak 2015). One quality encompasses the type of experiences wilderness should provide: “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation” (hereafter, “outstanding opportunities”) (Landres et al. 2015; Wilderness Act 1964). However, this phrase was not explicitly defined in the law; in fact, there has been and continues to be a lack of clarity about the meaning of the entire phrase (Dawson and Hendee 2009; Hendee, Stankey, and Lucas 1978; USDA Forest Service 2005). In a 2010 report, the United States Forest Service’s (USFS’s) Wilderness Advisory Group (Carlson et al. 2010, p. 2) wrote that

Regulations and policy require the Forest Service to provide outstanding opportunities but provide no further direction. There are no definitions of key terms and no guidance regarding indicators or desired conditions. There is little or no policy that identifies when management action is needed, and no guidance on how to achieve the management objectives.

Various scholars have provided rich insight about wilderness as a cultural and legal construct (e.g., Cronon 1996; Nash 2014; Sutter 2002); however, this scholarship has generally not addressed questions of congressional intent. Further, although some scholars have profitably addressed the meaning and nature of wilderness experiences – including solitude and primitive and unconfined types of recreation – their analyses did not include many primary materials related directly to the legislative history of the act. For instance, Hollenhorst and Jones (2001) explored historical ideas about solitude, but primarily used secondary materials unrelated to the legislative history of the act. Borrie and Roggenbuck (2001) also investigated historical perspectives on the wilderness experience, but their focus was on materials unrelated to the legislative process associated with the law. Borrie (2004) addressed the primitive aspect of the wilderness experience but did not delve into materials written by individuals directly responsible for crafting the language of the law. In exploring the meaning of “unconfined recreation,” McCool (2004) provided a contemporary perspective rather than using historical materials. So, although these efforts productively explored the conceptual meanings of the different aspects of “outstanding opportunities,” they did not utilize legislative materials that would be useful for establishing congressional intent. Thus, a rigorous analysis is needed of primary source materials pertaining to “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation.”

Statutory decrees, such as the Wilderness Act, mandate that federal land management agencies manage and regulate natural resources for particular ends as established by Congress. The Public Land Law Review Commission (PLLRC), which was established in 1964 to review federal public land laws, argued that agencies should be required to provide “administrative interpretation of statutory language” to ensure that policies are being carried out in accordance with congressional intent (PLLRC 1970, p. 251). Unfortunately, congressional intent is not typically clear from the language of statutes alone. According to Mortimer (2002, p. 910), Congress enacts “broad, vague legislation” to meet “various and oft conflicting goals,” which leaves federal land managers “saddled with the unenviable task of interpreting amorphous statutes.” The phrase “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation” exemplifies this issue. Fortunately, congressional documents are useful resources for discerning congressional intent (McKinney 2002).

We present an analysis of historical materials associated directly with the legislative process involved in the passage of the Wilderness Act to explore how “outstanding opportunities” and its parts were historically understood. We examined how a variety of people, such as prominent wilderness advocates and members of Congress and the public, described or used these terms in more than 6,000 pages of the 18 congressional hearings conducted prior to the passage of the law in 1964. Specifically, we dissect the parts of the phrase “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation” (from Section 2[c] of the Wilderness Act) through an examination of how the terms “solitude,” “rugged,” “primitive,” and “unconfined” were represented and likely understood by participants in the wilderness bill hearings. Based on our review, we will argue that (1) “solitude” and “primitive and unconfined” were considered conceptually distinct prior to the passage of the law, and (2) “solitude” in particular was envisioned as a multifaceted concept. Further, we describe the ways that contemporary management and monitoring could reflect the complexity of solitude to better align agency stewardship efforts with the congressional intent behind the Wilderness Act.

The Emergence of “Outstanding Opportunities for Solitude”

The phrase “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation” was not in the text of the original bill presented to Congress, and “wilderness” was more broadly defined than what was ultimately included in the Wilderness Act of 1964. The first version of the wilderness bill only contained a brief definition of wilderness: “An area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a member of the natural community who visits but does not remain and whose travels leave only trails” (S. 4013 1956, p. 3). Senator James E. Murray introduced an important revision of the bill, S. 3809, on July 2, 1960, and Representative John P. Saylor presented a companion bill, H.R. 12951, to the House of Representatives the same day. These included nearly 30 changes from the previous bill (Allin 1982). Among those changes was a clarification of the definition of “wilderness” that had not previously been articulated; it was now additionally defined as an area of undeveloped Federal land without permanent improvements or human habitation which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions and which (1) generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable; (2) has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a rugged, primitive, and unconfined type of outdoor recreation; (3) is of sufficient size as to make practicable its preservation and use in an unimpaired condition; and (4) may also contain ecological, geological, archaeological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value. (S. 3809, 1960; emphasis added) By 1964, the language of the experiential mandate had changed to exclude the words “rugged” and “outdoor,” but the remainder of the phrase was retained in the Wilderness Act.

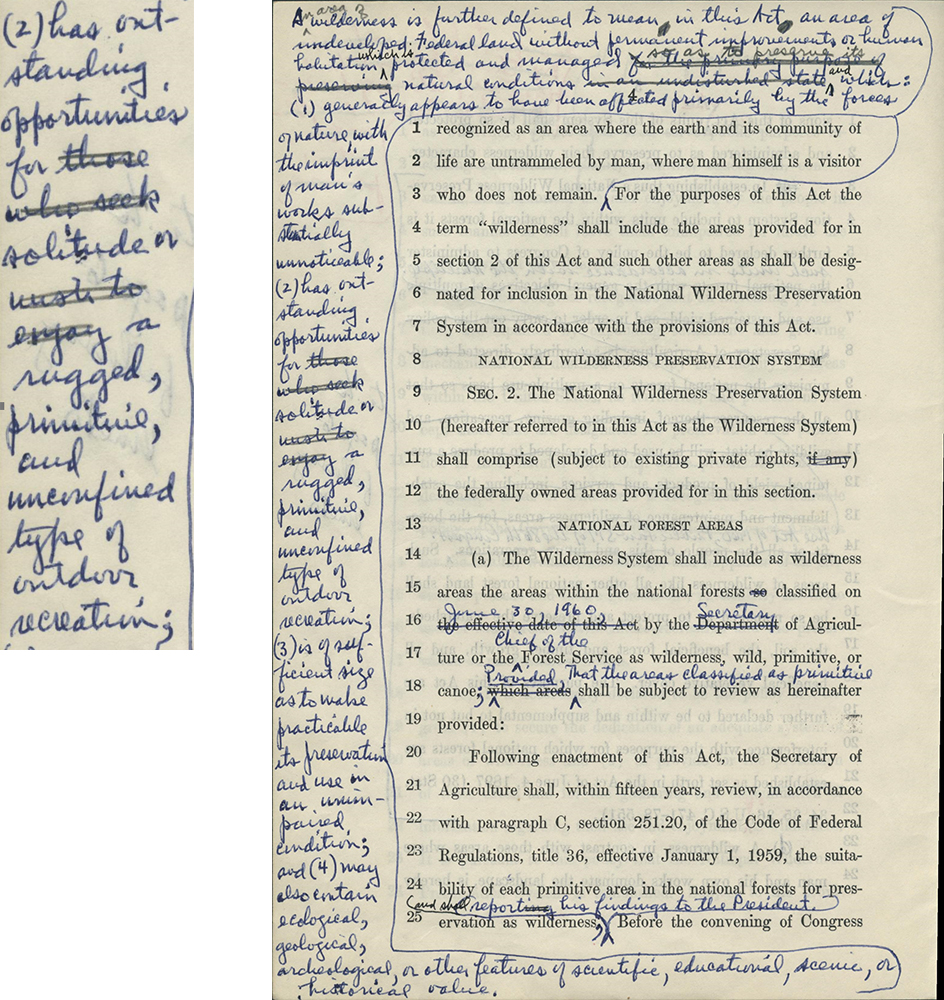

In the days preceding the completion of S. 3809 and H.R. 12951, Howard Zahniser, the chief architect of the Wilderness Act and executive director of the Wilderness Society at the time, wrote perhaps the clearest version of “outstanding opportunities” in a draft amendment of the bills. In the margins of the previous bill, H.R. 10621, he wrote, “An area of wilderness… (2) has outstanding opportunities for those who seek solitude or wish to enjoy a rugged, primitive, and unconfined type of outdoor recreation” (Zahniser 1960) (Figures 1 and 2). This text could be interpreted to suggest that “solitude” and “rugged, primitive, and unconfined” were distinct. The use of the plural pronoun “those” seems to speak to two distinct user groups who valued two unique aspects of wilderness environments: (1) solitude and (2) a rugged, primitive, and unconfined type of outdoor recreation. More importantly, however, the purposeful usage of two different verbs (i.e., “seek” and “wish”) prefacing these experiential aspects of wilderness suggested Zahniser felt these attributes of the wilderness experience – “solitude” and “rugged, primitive, and unconfined” – were conceptually distinct.

Figure 1 – A close-up of the first known appearance of “outstanding opportunities” in the wilderness bill drafted on H.R. 10621 (Zahniser 1960). From the Conservation Collection in the Genealogy, African American and Western History Library at the Denver Public Library.

Figure 2 – The first known appearance of “outstanding opportunities” in the wilderness bill drafted on H.R. 10621 (Zahniser 1960). From the Conservation Collection in the Genealogy, African American and Western History Library at the Denver Public Library.

Despite the apparent distinction between “solitude” and “primitive and unconfined” within this first known written definition of “outstanding opportunities,” the phrase was changed slightly before it ever reached the House or Senate floors for a vote. In the margins of H.R. 10621, later changes were made in which “those who seek” and “wish to enjoy” were distinctly crossed out (Zahniser 1960). It is unclear why these edits were made; however, the wilderness management community has lived with their ambiguity ever since. Some have argued that the word “or” in the phrase meant that wilderness managers may provide for either “solitude” or “a primitive and unconfined type of recreation” in wilderness areas (Clark 1976; DeFelice 1975). Others have argued that “primitive and unconfined” was an attempt to clarify or provide richer meaning to the preceding “solitude” (Hendee et al. 1978; Hendee and Dawson 2002; Hendee, Stankey, and Lucas 1990; Worf 2001; Worf et al. 1972).

“…..has outstanding opportunities for those who seek solitude or wish to enjoy a rugged, primitive, and unconfined type of outdoor recreation”

In this featured manuscript we present an analysis of historical materials associated directly with the legislative process involved in the passage of the Wilderness Act to explore how “outstanding opportunities” and its parts were historically understood. We did this by exploring and categorizing how a variety of people, such as prominent wilderness advocates and members of Congress and the public, described or used “solitude,” “rugged,” “primitive,” and “unconfined” during the congressional hearings prior to the passage of the law. For instance, if a hearing participant said that they “sought the solitude of quiet places,” we interpreted that to mean sound was an important aspect of solitude for that participant. Based on our review, we will argue that (1) “solitude” and “primitive and unconfined” were considered to be conceptually distinct prior to the passage of the law and (2) that “solitude” in particular was envisioned as a multifaceted concept. We conclude with our thoughts on the ways that contemporary management and monitoring could reflect the complexity of solitude to better align agency stewardship efforts with congressional intent.

Sensory Escape from the City

For wilderness advocates prior to the passage of the Wilderness Act, wilderness solitude was multifaceted. It was also integral to wilderness itself. In fact, Zahniser responded to an open-ended question in a survey conducted by the Library of Congress’s Legislative Reference Service (hereafter, the LRS survey) about the Wilderness Society’s support for wilderness by including the first point of the fledging organization’s platform from the inaugural issue of The Living Wilderness (Wilderness Society 1935, p. 2): “The wilderness (the environment of solitude) is a natural mental resource having the same basic relation to man’s ultimate thought and culture as coal, timber, and other physical resources have to his material needs” (National Wilderness Preservation Act [NWPA] Hearings 1957e, p. 167). Zahniser felt his responses to this survey would be valuable to people reviewing the hearings in interpreting the meaning of the bill and thus submitted his full responses as his first item to be included in the record of the hearings (NWPA Hearings 1957e). Solitude was also prominent in others’ descriptions of wilderness and the wilderness experience and was understood to be facilitated in a particular type of wild landscape – one that was away from the sights and sounds of civilization, that was generally large in size, and that felt remote and natural. In testimony in support of the act, descriptions of an increasingly mechanized civilization were often used as a foil to elucidate the meaning of wilderness solitude. Sensory references to sight, sounds, and smells were commonly used to represent civilization and cities as chaotic, confusing, and unnatural. Wilderness advocates argued for the necessity of “solitude” in wilderness to escape the unnatural sensory overload of modernity and the “stress and strain and the tension of city life” (NWPA Hearings 1961a, p. 635).

“The wilderness (the environment of solitude) is a natural mental resource having the same basic relation to man’s ultimate thought and culture as coal, timber, and other physical resources have to his material needs”

Advocates lamented the artificial noise that dominated urban life, and the country’s remaining wild places were thought to be threatened by the auditory encroachment of civilization. Wilderness proponents sought to escape the keynote sounds in the city: the horns, radios, and motors. For example, Representative Saylor described civilization as “raucously noisy” and asserted that humans have a “deep need for areas of solitude and quiet” that could be found in wilderness (NWPA Hearings 1957b, p. 71). In another example, a wilderness advocate stated at the 1964 hearings in Las Vegas that wilderness was “essential… to enjoy nature’s beauty and solitude – a place to get away from the pressure and noise of our modern city living” (NWPA Hearings 1964d, p. 1028). Further, at the 1964 hearings in Denver, an advocate said that Americans need “areas of peace and solitude away from the noisy, mechanized, and humdrum existence of the industrial conurbations” (NWPA Hearings 1964a, p. 339). Thus, the possibility of physical escape from the city was important, and anxiety about artificial noise in the city fueled support for a wilderness bill.

Artificial noise in wilderness, not just in the city, was detrimental to solitude. Motorized vehicles, such as automobiles and aircraft, were commonly used as examples of artificial noise that degraded solitude in wild places. For instance, Olaus Murie lamented that “jeeps are nosing into the back country. Aircraft is breaking the peace and solitude of charming mountain valleys and secluded lakes” (Murie 1953, as cited in NWPA Hearings 1957c, p. 139). Zahniser submitted evidence stating that “the airplane by its noise destroys for man in the canoe the intangible, almost indescribable quality of the wilderness, a quality compounded of silence and solitude and a brooding sense of peace that sinks into the spirit” (Martin 1948, p. 150, as cited in NWPA Hearings 1957e, pp. 180–181). In discussing the impact of Mission 66, a development program that sought to modernize the US National Parks, a hearing participant argued that backpacking was threatened as a “means of finding solitude and serenity” because “it is often interrupted by the noises of jeeps and tote-gotes [off-road motorcycles]” (NWPA Hearings 1964b, p. 493). Thus, escape from the sensory overload of the city and a disdain for its sensory encroachment into wild places were intertwined in wilderness advocates’ representations of solitude. Sound mattered to solitude.

Wilderness did more than provide a refuge to escape the sensory overload of the city; participants testified that it offered unique sensory experiences of its own that heightened one’s sense of solitude. For example, Wilderness Society member Pauline Dyer described some keynote sounds of the wilderness that facilitated solitude:

[Wilderness’s] impact is greatest when they [visitors] are absorbing in peaceful solitude, the voices of wind rustling the needles or leaves in a forest or whipping it during a storm, or listening to the symphonies composed by rivers and creeks, birds or frogs, with the added possibility of a note from a bugling elk. These are the sounds of wilderness’ aliveness. (NWPA Hearings 1962b, p. 1384)

Other senses, such as sight, were also evoked in testimonies about wilderness solitude. For instance, one wilderness proponent said that the “re-creation of urban man” occurs when he gets into “solitude to have unspoiled views and to hear the original music of nature, and to see the natural providences of life that made America great” (NWPA Hearings 1961b, p. 797). Solitude, used in these types of contexts, was related to a multisensory experience of sound and vision.

The spiritual benefits of wilderness solitude were often connected to the sensory experience of wilderness. Zahniser’s most lengthy response to the LRS survey about the values of wilderness was his description of wilderness’s spiritual values. He framed this response with a discussion of the Reverend William H. H. Murray’s Adventures in the Wilderness, or, Camp Life in the Adirondacks (1869). While discussing “real wilderness travel,” Zahniser used Murray’s words:

In its vast solitude is a total absence of sights and sounds of duties, which keep the clergyman’s brain and heart strung up, the long year through, to an intense, unnatural, and often fatal tension. There, from a thousand sources of invigoration, flow into the exhausted mind and enfeebled body currents of strength and life. (NWPA Hearings 1957e, p. 188)

In his response, Zahniser noted that Murray was writing in the 19th century and pondered the “comparative quiet” – another evocation of the senses – of that time relative to postwar industrial America. Later in Zahniser’s section on the spiritual benefits of wilderness – which were deeply connected to solitude – he used an excerpt from Robert Marshall’s (1930) “The Problem of the Wilderness,” which conveyed the salience of the senses in the spiritual experience of wilderness. For Zahniser and Marshall, wilderness was a multisensorial experience:

Another singular aspect of the wilderness is that it gratifies every one of the senses. There is unanimity in venerating the sights and sounds of the forest. But what are generally esteemed to be the minor senses should not be slighted. No one who has ever strolled in springtime through seas of blooming violets, or lain at night on boughs of fresh balsam, or walked across dank holms in early morning can omit odor from the joys of the primordial environment. No one who has felt the stiff wind of mountaintops or the softness of untrodden sphagnum will forget the exhilaration experienced through touch. Nothing ever tastes as good as when it’s cooked in the woods is a trite tribute to another sense. Even equilibrium causes a blithe exultation during many a river crossing on tenuous foot-log and many a perilous conquest of precipice. (NWPA Hearings 1957e, p. 190 quoted from Marshall [1930, p. 145])

Thus, for Zahniser, the senses mattered a great deal to wilderness solitude and the spiritual benefits it could cultivate.

“Another singular aspect of the wilderness is that it gratifies every one of the senses.”

The Importance of Large, Remote, Natural Areas to Solitude

Beyond the sensory experience, the wilderness landscape itself affected one’s ability to experience solitude. Specifically, advocates thought that (1) solitude was facilitated by “natural” landscapes, (2) visitors’ experience of solitude was dependent on large wilderness areas, and (3) wilderness users’ feelings of remoteness from other users and human development facilitated solitude.

To experience wilderness solitude, advocates argued that they had to recreate in a particular type of landscape with characteristics they felt were unique to wilderness. For them, city parks, open spaces, or other undeveloped land were inadequate. For example, Zahniser submitted that “outing areas in which people may enjoy the nonprimitive forest are highly desirable for many pentup [sic] city people who have no desire for solitude, but such areas should not be confused in mental conception or administration with those reserved for the wilderness” (The Wilderness Society 1935, p. 2, as cited in NWPA Hearings 1957e, p. 167).

A commonly used adjective to describe wilderness as a place to experience solitude was “primeval.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, primeval was understood at the time as “primal, original, primitive” (“Primeval,” 2017). When discussing motivations for wilderness recreation, Sigurd Olson stated people would visit wild places to “catch a hint of the primeval, a sense of the old majesty and mystery of the unknown. A mere glimpse of the wild set in motion dormant reactions long associated with solitude” (NWPA Hearings 1957a, p. 50-54). In another example, Michael Nadel, later president of The Wilderness Society, submitted an article to a hearing written by the journalist John B. Oakes that captured the “intangible” aspects of the wilderness. In the article, Oakes (1956, p. 341) alluded to the primeval when he stated, “By ‘intangible,’ we mean scenery and solitude, open country and quiet places, expanses of mountain, plain, forest, and seashore, where some of the spiritual quality of primeval America may be retained for this and future generations” (NWPA Hearings 1957f, pp. 389–390).

Hearing participants also referred to places that facilitated solitude as “natural,” “unspoiled” or “untouched.” C. B. Morse, the manager of the National Forest Recreation Association in California, stated that “the over-mounting pressures of modern life make it necessary for people to ‘get away from it all’ and have solitude in natural and inspiring surroundings” (NWPA Hearings 1958a, p. 524). Another felt that visitors could find “solitude and peace of mind” in the “precious, dwindling storehouse of unspoiled, untouched nature” of wilderness areas (NWPA Hearings 1962a, p. 1306). Thus, solitude was a multifaceted experience partially dependent on the natural quality or characteristics of the landscape itself.

In addition to the characteristics of landscapes, wilderness acreage also mattered to solitude. Referencing the size of wilderness, Zahniser submitted the following text from Edwin Way Teale’s (1957, p. 108) essay “Land Forever Wild” at a wilderness bill hearing in 1957: “The wilderness, by its nature, demands solitude. It requires as much remoteness from man and his works as possible. Only in comparatively large areas can a wilderness continue to maintain its wilderness character” (NWPA Hearings 1957e, p. 233). Relevant to this, Keyser’s (1949) LRS report – which is based on findings from the aforementioned LRS survey of a variety of groups in the United States – suggested that, although there was no consensus among the respondents on an exact amount of acreage needed for a place to be considered wilderness, “the size most often mentioned” was more than 100,000 acres (400,468 ha) (NWPA Hearings 1957e, p. 46). One respondent felt that wilderness areas should be “large enough so that one may travel perhaps for several days without coming into contact with any evidence of civilization” and went on to finalize the point by stating that “isolation is a major requirement” (Keyser 1949, p. 47).

The feeling of remoteness – not just the acreage – was another important aspect of solitude. For instance, overcrowding of wilderness was a concern of some wilderness advocates. In an example related to the impact of crowds, an advocate noted the increasing rareness of “tranquility and solitude” and said that “thousands of people can’t enjoy solitude together” (NWPA Hearings 1964e, p. 1377). Another person stated, “It should be thoroughly understood that wilderness-type recreation, by its very nature, is only to be enjoyed by a limited few persons at any one time or place. A crowded wilderness area quickly loses its qualities of peace and solitude” (NWPA Hearings 1964c, p. 942).

Feelings of remoteness were also impacted by the physical presence of modern developments on the landscape, such as roads. Olaus Murie said that wilderness areas with “no roads whatsoever” were places where “one can find solitude and true wilderness recreation” (Murie 1953, as cited in NWPA Hearings 1957c, p. 129). Regarding roads, Zahniser, used text from The Wilderness Society’s platform (1935, p. 2) as part of his testimony: “Scenery and solitude are intrinsically separate things; the motorist is entitled to his full share of scenery, but motorways and solitude together constitute a contradiction” (NWPA Hearings 1957e, p. 167). Thus, roads – given their simple presence and because they were conduits for the sights and sounds of civilization – were seen to degrade solitude, which is unsurprising given the general antiroad ethos of wilderness advocates (Sutter 2002).

“Scenery and solitude are intrinsically separate things; the motorist is entitled to his full share of scenery, but motorways and solitude together constitute a contradiction.”

“A Primitive and Unconfined Type of Recreation”

Compared to “solitude,” the terms “rugged,” “primitive,” and “unconfined” were less prevalent in descriptions of the wilderness experience during the hearings. Nevertheless, there is enough material to show that these terms were not used to clarify the meaning of “solitude” but were in fact conceptually distinct from it.

In the NWPA hearings, “rugged” or its variations (e.g., “ruggedness”) typically referred to the physical strength of individuals. For example, J. W. Penfold, the conservation director of the Izaak Walton League of America, said that he could not “enjoy or participate in the ruggedness of some wilderness experience, but we certainly think that my sons should have full opportunity for it, and not be limited by my own weaknesses, shortcomings, and so on” (NWPA Hearings 1957d, p. 153). For him, “ruggedness” was tied to physical strength. Olaus Murie believed that a life of wilderness experiences was “not to be ashamed of, a life of rugged endeavor and high spiritual reward, not to be lightly discarded in the modern reach for ease and gadgets” (NWPA Hearings 1957c, p. 147). In addition, Cecil C. Clarke of the Washington State Reclamation Association – an opponent of the bill – argued that limiting the use of wilderness areas to horsepacking and hiking meant “that only a comparatively few persons, those who are physically rugged enough to stand hiking or those wealthy enough to hire pack strings, would ever have the use of these public lands which should be available to all persons” (NWPA Hearings 1959a, p. 163). Another critic of the bill simply stated that “older people have not the stamina for such rugged outdoor activity” (NWPA Hearings 1959b, p. 281).

While “rugged” typically referred to the physical difficulty of wilderness recreation “primitive” referred to other facets of the wilderness experience. For instance, Sigurd Olson felt that the wilderness experience was needed for people to enact their primitive nature when he stated in testimony that

modern man, in spite of his seeming urbanity and sophistication, is still a primitive roaming the forests of this range, killing his meat, scratching the earth with a stick, gathering nuts and fruits and harvesting grain between the stumps of burned out trees, that [sic] the old fears as well as the basic satisfactions are still very much a part of him. (NWPA Hearings 1957a, pp. 50–52)

Congressman Saylor also evoked the primitive when he said that “in our preservation of wilderness and our encouragement of the hardy recreation that puts a man or a woman or a red-blooded child on his own in the face of primitive hardships we can help meet this need for maintaining a nation of strong, healthy citizens” (NWPA Hearings 1957b, p. 71).

Primitive recreation also referred to permissible types of travel in the wilderness. C. B. Morse stated that the objective of the L-20 wilderness areas managed by the USFS was “to preserve in primitive condition, for primitive modes of travel, sufficient areas for people of succeeding generations, for all time, to have examples of how the pioneers had to travel in the exploration and settlement of this country” (NWPA Hearings 1958a, p. 524). In Zahniser’s (1957e, p. 170) response to the LRS survey, he quoted Robert Marshall (1930, p. 141), stating that wilderness “preserves as nearly as possible the primitive environment. This means that all roads, power transportation, and settlements are barred. But trails and temporary shelters, which were common long before the advent of the white race, are entirely permissible.” Zahniser (NWPA Hearings 1957e, p. 192) also provided a detailed list of permissible uses of wilderness areas in his response to the LRS survey:

Hiking (with or without pack animals), canoeing and boating with paddle or oar, horseback travel, mountain climbing, skiing (especially ski-touring) and such other activities which may be part of the outdoor living when one is dependent on equipment he carries on his own back or on pack animals and is unaided by motorized transportation. Ecological recreation, nature study in all its phases, and photographing are common and appropriate. Fishing is permissible, according to present regulations, in national parks as well as in national forest wilderness areas, while hunting is prohibited in the parks and permitted in the national forest areas.

Thus, for Zahniser, an activity that was permissible in wilderness areas would be one that enabled visitors to “relive the lives of ancestors” and that “perpetuates not only the scene of the pioneering activities of the first white men in this hemisphere, but also a still more ancient scene [i.e., Native Americans]” (NWPA Hearings, 1957e, p. 183). Given this, it was important for Zahniser that the activities allowed in wilderness were ones in which a person was unaided by motorized transportation and that facilitated the re-creation of the past.

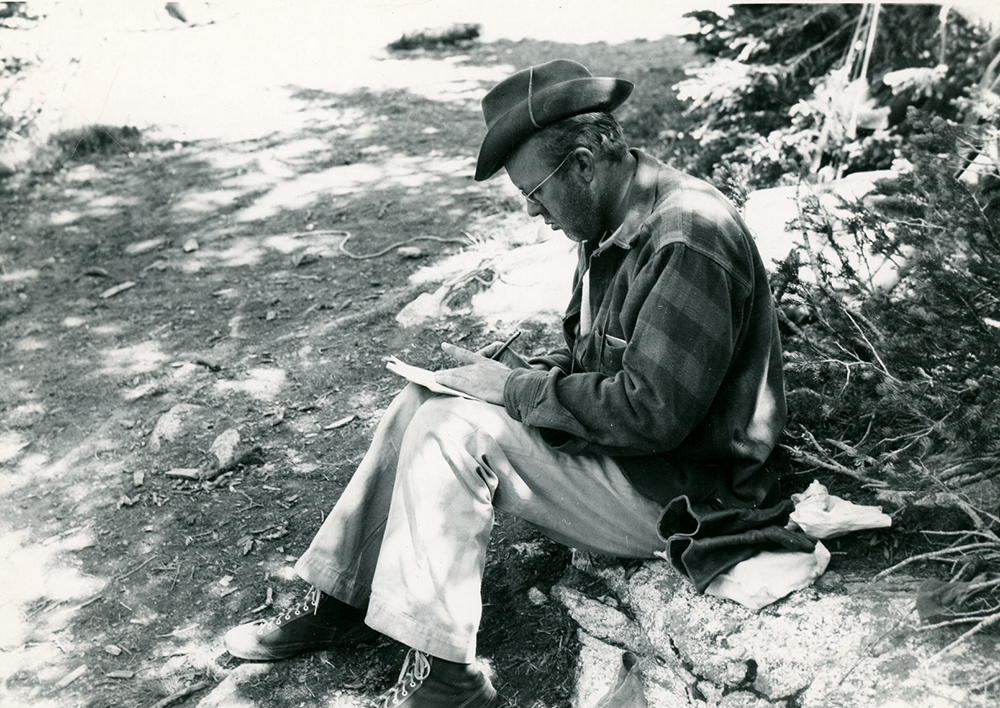

Figure 3 – Howard Zahniser. From the Conservation Collection in the Genealogy, African American and Western History Library at the Denver Public Library.

Based on our review, the term “unconfined” was not used illustratively in the hearings; it typically appeared only in references to the specific text of the proposed bills. However, Zahniser provided some material as evidence in the hearings from which his thinking may potentially be inferred. Specifically, he included a discussion of the potential need to ration use in wilderness areas in his response to the LRS survey. He wrote that it was paramount to “give the maximum number of individuals a true wilderness experience, with emphasis on the authenticity of the wilderness” (NWPA Hearings 1957e, p. 193). To him, a “true wilderness experience” was threatened by excessive numbers of people. Related to how “unconfined” is understood today as a lack of visitor restrictions (e.g., Griffin 2017; Landres et al. 2015; McCool 2004), he described a manager’s dilemma of limiting the number of users in wilderness or imposing strict rules on visitor behavior. His response aligned with Hendee and Lucas’s (1973) later argument that mandatory permits are sometimes needed as a management tool to protect the wilderness resource. Specifically, Zahniser felt that

Eventually it may be that wilderness use will have to be rationed. This would seem to be the alternative to administering the wilderness for the accommodations of large numbers of people at a time, which would jeopardize the wilderness itself and the wilderness “atmosphere” and at the same time would require regulation or regimentation of the visitors in such a way as to destroy the “freedom of the wilderness” and to nullify the escape from restrictions that is so important a part of the wilderness experience. (NWPA Hearings 1957e, p. 193)

Thus, he felt that “the true wilderness choice seems certain to be the limitation of numbers of users of such an area at a time, on the basis of preserving not only the wilderness but also the authenticity of the wilderness experience” (NWPA Hearings 1957e, p. 194). He argued that reservation systems that limit use in wilderness, “although appalling at first thought,” would preserve a “true wilderness experience” more than the imposition of strict regulations on visitor behavior (NWPA Hearings 1957e, p. 194).

Conclusion and Implications

We have tried to provide some clarity about the meaning of “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation” from Section 2(c) of the Wilderness Act of 1964 by using testimony from legislative hearings. We were motivated to engage in this research primarily because the federal land management agencies responsible for wilderness stewardship lack clear guidance on how to preserve “outstanding opportunities.” Our investigation supports the interpretation that “solitude” and “primitive and unconfined” were understood as conceptually distinct. Zahniser’s original definition of wilderness as having “outstanding opportunities for those who seek solitude or wish to enjoy a rugged, primitive, and unconfined type of outdoor recreation,” combined with the disparate ways these concepts were historically represented in the wilderness bill hearings, suggests that “primitive and unconfined” were likely not understood as synonymous with “solitude.” (Figure 3).

Our investigation did not yield definitive answers about the intended meaning of “or” in Section 2(c). The original phrase can be interpreted in at least two ways. First, it could have meant that a wilderness area should simultaneously serve two user groups: (1) those who seek solitude and (2) those who wish to enjoy a rugged, primitive, and unconfined type of outdoor recreation. Alternatively, it could have meant that a wilderness area should provide either (1) solitude or (2) a rugged, primitive, and unconfined type of outdoor recreation. Because of the ambiguity of the intended usage of “or,” the debate about what wilderness areas should provide cannot be definitively settled without further investigation. However, we suggest that “solitude” and a “primitive and unconfined” type of recreation are both essential to retain the character of every wilderness area. “Solitude” was so predominately discussed in the context of wilderness experience – and even as a defining feature of wilderness itself – that we would find it surprising if wilderness proponents would have felt that an area of wilderness without opportunities for solitude would retain its wilderness character. Yet because of the historical importance of “primitive and unconfined” recreation – and because of the relatively clear guidance from Zahniser himself on the permissible uses of wilderness – we would find it equally surprising if proponents of the bill thought areas allowing impermissible uses of wilderness would still retain their wilderness character. Thus, we believe, as Zahniser’s original phrasing suggests, that wilderness areas ought to have outstanding opportunities for both types of people: those who seek solitude and those who wish to enjoy a rugged, primitive, and unconfined type of outdoor recreation.

Our analysis also suggests that there was consistency with how “solitude” was represented and understood by wilderness advocates prior to the passage of the Wilderness Act. In particular, escape from the artificial noise of the city and immersion in the natural soundscapes of wilderness were central, although sight, and to a lesser extent smell and touch, were also salient. However, the multisensorial experience was not the sole characteristic, as remoteness, large acreage, natural landscapes, a lack of crowds, and the absence of roads were all paramount to wilderness solitude.

In general, solitude is monitored and managed in relatively unidimensional ways today. Although the wilderness character monitoring framework captures the complexity of solitude in meaningful ways by documenting various factors that impact it both within and outside wilderness boundaries (Landres et al. 2015), many wilderness management plans only track opportunities for solitude by monitoring social encounters (i.e., the number of people or groups that recreationists see or hear in wilderness). Although the number of users did have an impact on solitude for wilderness advocates and should continue to be emphasized in contemporary stewardship, encounters alone inadequately operationalize solitude because they only capture a sliver of the concept, neglecting other facets that are in line with congressional intent. Thus, as wilderness management plans are updated and the federal agencies integrate the wilderness character framework into planning and monitoring, contemporary wilderness stewards could manage and monitor wilderness solitude in ways that are more aligned with congressional intent. For instance, natural soundscape monitoring, which measures anthropogenic versus natural sounds, and night sky monitoring, which measures the amount of artificial light in the night sky, both capture parts of the sensory experience and remoteness of wilderness and could be important tools for stewards to prioritize to better reflect the intended meaning of solitude.

Beyond describing the richness of solitude, evidence from the hearings support the contention that the five qualities of wilderness character are deeply intermingled and interrelated (Landres et al. 2015). For example, natural and undeveloped environments were described as deeply intertwined with the congressional intent behind “outstanding opportunities for solitude.” Therefore, we believe that wilderness managers should, when appropriate, make local determinations about whether to include measures related to the natural or built environment to assess the state and trends of solitude to better ensure they reflect the multifaceted concept of solitude as understood by architects of the Wilderness Act. Although such improvements do not quantify unobservable, intangible, or ineffable aspects of solitude, they would nevertheless better align agency efforts with the congressional intent behind the “outstanding opportunities” quality of wilderness character and, because wilderness was explicitly defined by some of its earliest advocates as “an environment of solitude,” elevate the evident importance of the wilderness experience in contemporary stewardship.

JESSE M. ENGEBRETSON is a postdoctoral research associate in the Department of Forest Resources at the College of Food, Agricultural, and Natural Resource Sciences at the University of Minnesota; email: enge0322@umn.edu.

TROY E. HALL is department head and professor in the Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society in the College of Forestry at Oregon State University; email: troy.hall@oregonstate.edu.

References

References

Allin, C. W. 1982. The Politics of Wilderness Preservation. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Borrie, W. T. 2004. Why primitive experiences in wilderness? International Journal of Wilderness 10(3): 18–20.

Borrie, W. T, and J. W. Roggenbuck. 2001. The dynamic, emergent, and multi-phasic nature of on-site wilderness experiences. Journal of Leisure Research 33(2): 202–228.

Carlson, T., D. Cole, D. Finnan, K. Hood, and J. Weise. 2010. Ensuring outstanding opportunities for quality wilderness visitor experiences: Problems and recommendations. Retrieved from http://www.wilderness.net/NWPS/documents/FS/Outstanding%20Opportunities%20for%20Visitor%20Experiences_WAG_Report.pdf.

Clark, R. W. 1976. Management alternatives for the Great Gulf Wilderness Area. In Backcountry Management in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, ed. W. R. Burch and R. W. Clark (pp. 22–27). New Haven, CT: Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.

Cronon, W. 1996. The trouble with wilderness. Environmental History 1(1): 20–25.

Dawson, C. P., and J. C. Hendee. 2009. Wilderness Management: Stewardship and Protection of Resources and Values, 4th ed. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

DeFelice, V. N. 1975. Wilderness is for using. American Forests 81(6): 24–26.

Dvorak, R. 2015. Keeping it wild 2. International Journal of Wilderness 21(3): 6–9.

Griffin, C. B. 2017. Managing unconfined recreation in wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 23(1): 13–17.

Hendee, J. C., and R. C. Lucas. 1973. Mandatory wilderness permits: A necessary management tool. Journal of Forestry 7: 206-209.

Hendee, J. C., G. H. Stankey, and R. C. Lucas. 1978. Wilderness Management. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.

———. 1990. Wilderness Management, 2nd ed. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Hendee, J. C., and C. P. Dawson. 2002. Wilderness Management: Stewardship and Protection of Resources and Values. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Hollenhorst, S. J., and C. D. Jones. 2001. Wilderness solitude: Beyond the social-spatial perspectives. In Visitor Use Density and Wilderness Experience: Proceedings (Proceedings RMRS-P-20), ed. W. A. Freimund and D. N. Cole (pp. 56–61). Ogden, UT: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Keyser, C. F. 1949. The Preservation of Wilderness Areas (an Analysis of Opinion on the Problem) (Committee Print 19). Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Legislative Reference Service.

Landres, P., C. Barns, S. Boutcher, T. Devine, P. Dratch, A. Lindholm,… E. Simpson. 2015. Keeping It Wild 2: An Updated Interagency Strategy to Monitor Trends in Wilderness Character across the National Wilderness Preservation System (General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-340). Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Marshall, R. 1930. The problem of the wilderness. Scientific Monthly 30(2): 141–148.

Martin, H. H. 1948. Embattled wilderness. Saturday Evening Post 221(13): 22, 149–156.

McCool, S. F. 2004. Wilderness character and the notion of an “unconfined” experience. International Journal of Wilderness 10(3): 15–17.

McKinney, R. J. 2002. An overview of the Congressional Record and its predecessor publications: A research guide. Law Library Lights 46(2): 16–22.

Mortimer, M. J. 2002. The delegation of law-making authority to the United States Forest Service: Implications in the struggle for national forest management. Administrative Law Review 54(3): 907–982.

Murie, O. 1953. Wild country as a national asset. The Living Wilderness 18(45): 1–27.

Murray, W. H. H. 1869. Adventures in the Wilderness, or, Camp Life in the Adirondacks. Boston, MA: Fields, Osgood, & Co.

Nash, R. 2014. Wilderness and the American Mind, 5th ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on H.R. 361, H.R. 500, H.R. 540, H.R. 906, H.R. 1960, H.R. 2162, and H.R. 7880, 85th Cong. 50–2, 50–4 (1957a) (testimony of Sigurd F. Olson).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on S. 1176, 85th Cong. 71 (1957b) (speech of John P. Saylor in the House of Representatives, Thursday, July 12, 1956 in testimony of Hubert H. Humphrey).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on S. 1176, 85th Cong. 128–29, 139 (1957c) (testimony of Olaus J. Murie).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on H.R. 361, H.R. 500, H.R. 540, H.R. 906, H.R. 1960, H.R. 2162, and H.R. 7880, 85th Cong. 153 (1957d) (testimony of J. W. Penfold).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on S. 1176, 85th Cong. 147, 167, 170, 180–81, 183, 188, 190, 192, 193, 194, 233 (1957e) (testimony of Howard Zahniser).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on S. 1176, 85th Cong. 389–390 (1957f) (testimony of Michael Nadel).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on S. 4028, 85th Cong. 524 (1958a) (testimony of C. B. Morse)

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on S. 1123, 86th Cong. 163 (1959a) (testimony of Cecil C. Clark).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on S. 1123, 86th Cong. 281 (1959b) (testimony of Louis A. Rozzoni).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on S. 174, H.R. 293, H.R. 299, H.R. 496, H.R 776, H.R. 1762, H.R. 1925, H.R. 2008, and H.R. 8237, 87th Cong. 635 (1961a) (testimony of Pete Cristo).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on S. 174, H.R. 293, H.R. 299, H.R. 496, H.R 776, H.R. 1762, H.R. 1925, H.R. 2008, and H.R. 8237, 87th Cong. 797 (1961b) (testimony of Roland Case Ross).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on S. 174, H.R. 293, H.R. 299, H.R. 496, H.R 776, H.R. 1762, H.R. 1925, H.R. 2008, and H.R. 8237, 87th Cong. 1306 (1962a) (testimony of Andrew J. Biemiller).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on S. 174, H.R. 293, H.R. 299, H.R. 496, H.R 776, H.R. 1762, H.R. 1925, H.R. 2008, and H.R. 8237, 87th Cong. 1384 (1962b) (testimony of Mrs. Pauline Dyer).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on Bills to Establish a National Wilderness Preservation System for the Permanent Good of the Whole People, and for Other Purposes, 88th Cong. 339 (1964a) (testimony of Miss M. H. Piggott).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on Bills to Establish a National Wilderness Preservation System for the Permanent Good of the Whole People, and for Other Purposes, 88th Cong. 493 (1964b) (testimony of Robert G. and Nancy C. Gustafson).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on Bills to Establish a National Wilderness Preservation System for the Permanent Good of the Whole People, and for Other Purposes, 88th Cong. 942 (1964c) (testimony of Mark Schoknecht).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on Bills to Establish a National Wilderness Preservation System for the Permanent Good of the Whole People, and for Other Purposes, 88th Cong. 1028 (1964d) (testimony of Curtis W. Mason).

National Wilderness Preservation Act: Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs on H.R. 9070, H.R. 9162, S. 4 and Related Bills, 88th Cong. 1377 (1964e) (testimony of Theodore M. Edison).

Oakes, J. 1956. Conservation: Dinosaur still in jeopardy. New York Times, May 13, p. 341.

Primeval. Def. 1a. 2017. In Oxford English Dictionary online. Retrieved from http://www.oed.com.

Public Land Law Review Commission. 1970. One Third of the Nation’s Land: A Report to the President and to the Congress by the Public Land Law Review Commission. Washington, DC: Public Land Law Review Commission.

S. 3809. 86th Cong. 1960.

S. 4013. 84th Cong. 195.

Sutter, P. S. 2002. Driven wild: How the fight against automobiles launched the modern wilderness movement. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Teale, E. W. 1957. Land forever wild. Audubon Magazine 59(3): 108.

USDA Forest Service. 2005. 10-Year Wilderness Stewardship Challenge Guidebook. Retrieved from www.wilderness.net/NWPS/documents/FS/guidebook.doc.

Wilderness Act, Public Law 88-577, 16 U.S.C. § 1131–1146 (1964).

The Wilderness Society. 1935. The Wilderness Society Platform. The Living Wilderness 1(1): 2.

Worf, W. 2001. The Forest Service recreation strategy spells doom to the National Wilderness Preservation System. International Journal of Wilderness 7(1): 15–16.

Worf, W., G. Jorgenson, and G. Lucas. 1972. National Forest Service Wilderness: A Policy Review. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.

Zahniser, H. 1960. Edits to H.R. 10621 for an untitled Senate bill. The Wilderness Society Records (Series 3, Box 4, File 25). Archives of the Conservation Collection, Denver Public Library, Denver, CO.

Read Next

WILD11 India: Nature-Based Solutions for Life, Livelihoods, and Love

We are pleased to tell you that the 11th World Wilderness Congress (WWC WILD11) will convene in Jaipur, India, in March 2020.

Jhalana: The Abode of the Urban Leopards

Imagine living in a crowded city of 3.1 million people and learning that amidst this human world, the huge buildings, the maddening crowd, and the deafening sounds lies a small, happy, and peaceful refuge where wild leopards rule.

Informing Planning and Management Through Visitor Experiences in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

Managing recreational opportunities and resource use while simultaneously working to conserve unique ecosystems for future use is particularly challenging in a vast and varied landscape such as Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.