Glacier Peak on the Pacific Crest Trail

Shared Stewardship and National Scenic Trails: Building on a Legacy of Partnerships

Stewardship

August 2020 | Volume 26, Number 2

PEER REVIEWED

National Scenic Trails (NSTs) connect people with the natural and cultural heritage of the United States. Theses trails also provide important opportunities for agencies to engage partners in trail stewardship and sponsorship. Partnership engagement ultimately promotes trails that provide outdoor experiences and learning opportunities for visitors and trail users. In the founding legislation of the National Trails System Act of 1968, Congress acknowledged the integral role of volunteers and trail groups and set out “to encourage and assist volunteer citizen involvement in the planning, development, maintenance, and management… of trails” (P.L. 90-543). Early partners played a critical role in encouraging Congress to embrace the concept of national trails and identifying trail routes. Today, the National Trails System includes 11 NSTs, as well as 19 National Historic Trails, and nearly 1,300 National Recreation Trails in 50 states. The entire system engages hundreds of stewardship partners working at local, regional, and national scales. Federal agencies and trail organizations work together to plan and maintain the trails, develop outreach programs, and connect with the public.

Trail administrators in public agencies have a dual commitment to encourage trail use and provide quality experiences to visitors while also conserving natural resources along trail corridors (P.L. 90-543).

Over the past several years, NSTs have experienced increased use. Expanded media coverage and popularity of published memoirs and motion pictures featuring long-distance thru-hiking have coincided with an uptick in visitation. With increasing trail use, diminished trail conditions have occurred along trail corridors. In designated wilderness areas, congestion and high-density use may conflict with wilderness values which emphasize solitude (Landres et al. 2008). In addition, landscape-scale environmental changes and extreme weather events (e.g., wildfires, floods, or droughts) have raised new concerns for trail safety and conditions (Brown 2018). Meanwhile, all agencies, federal, state, local and non-profit, face growing capacity challenges in recreation management, an aging public sector workforce, and declines in volunteerism nationally (Cerveny et al. 2020; Lewis and Cho 2011; Grimm and Dietz 2018). New partnership approaches may be needed to support trails and promote conservation along trail corridors because of these dynamic processes.

The purpose of this article is to understand the evolving role of partners in the shared stewardship of NSTs and to consider implications for trail and wilderness management. Shared stewardship approaches are motivated by a common vision for how lands might be managed to achieve shared benefits. The approach is implemented through partnerships and capitalizes on shared interests and values, encouraging the engagement of long-standing partners as well as new and diverse groups (Derrien et al. 2019). To frame our discussion, we examined popular and academic literature on natural resource partnerships and conducted semi-structured interviews with 14 key informants with in-depth knowledge of NST management and partner relations. We begin by providing background on NSTs and the role of partners in co-management of natural resources. We then explore the role of partners in the development and management of NSTs and identify benefits and challenges of NST partnerships. Throughout conversations we also identified nine priority issues related to overall trails management and in designated wilderness areas. We conclude with a future vision for shared stewardship for the National Trails System.

National Scenic Trails

The National Trails System Act of 1968 established the National Trails System to “provide for the ever-increasing outdoor recreation needs of an expanding population and in order to promote the preservation of, public access to, travel within, and enjoyment and appreciation of the open-air, outdoor areas and historic resources of the Nation.” (P.L. 90-543). The Act designated two trails, the Pacific Crest Trail and the Appalachian Trail, and established the process by which other trails could be designated. NSTs extend across multiple land jurisdictions managed by different federal agencies, tribes, state agencies, and private landowners. Each NST is assigned an administering federal agency responsible for coordination among local management entities, ensuring that the Act’s legislative requirements are met, and providing standards and technical assistance (USDA Forest Service 2014). Designations reach beyond the physical tread of trail, and include the trail corridor and associated natural, recreational, scenery, and cultural resources.

The National Trails System Act encourages the engagement of non-profit trail organizations and volunteers in many aspects of trail planning and management (P.L. 90-543). These partnerships demonstrate an early institutionalization of a public-private cooperative management system. Pre-existing trails were built and maintained by trail organizations and volunteers on the local level, and in many cases, these local organizations championed their trails for NST designation. Today, dozens of organizations at the local, regional, and national level support NSTs, as an integral component to their management (USDA FS 2014). The designation of NSTs has expanded public awareness of these vital trails and created opportunities for new ventures.

Many NSTs pass through federally designated wilderness areas and NST establishment has occurred in parallel fashion to the designation of wilderness along the trail corridor. Thus, wilderness is a frequent companion to the NST distance hiker. The Pacific Crest Trail passes through 48 federally designated wilderness areas, compared to 25 along the Appalachian Trail and 21 along the Continental Divide Trail. Trail segments in designated wilderness areas require different strategies for trail maintenance (e.g., the use of pack animals and cross-cut saws, and multiple-day trips led by individuals with special training). Maintaining these trail segments also requires consideration of wilderness values and addressing questions about how to preserve solitude in areas with rapidly increasing trail use. Trail administrators managing sections of the trail in wilderness seek to balance Wilderness Act goals to provide primitive experiences and the goals of the National Trails System Act to promote trail use and enjoyment.

Natural Resource Partnerships and Collaboration

Public land management agencies increasingly rely on partnerships to achieve mission-critical goals and to engage in shared stewardship of public lands and natural resources (Koontz et al. 2004). Co-management practices that share power and responsibility among federal and local partners are increasingly becoming important in governance and are useful for building trust, enhancing capacity, and sharing knowledge (Berkes 2009). When talking about partnerships, we refer to the US Forest Service Partnership Handbook, which describes a partnership as “relationships between the people, organizations, agencies, and communities that work together and share interests” (National Forest Foundation 2005, p. 3). A partnership can be formal, (e.g., agreement, memorandum of understanding, or contract), or informal. They also can involve multiple parties and include governmental, nonprofit, or private entities (Seekamp and Cerveny 2010). Partnerships are widely recognized as an important way to share responsibility for management across multiple organizations and expand public involvement in resource conservation (Absher 2010; Koehler and Koontz 2008). Many factors have been identified as elements of successful partnerships among federal and non-federal partners, including: shared vision, clear pathway for achieving this vision, leadership, resources, organizational commitment, formal agreements, and concrete accomplishments (McPadden and Margerum 2014; Ansell and Gash 2009).

Shared stewardship requires building social capital, nurturing nascent partnerships, and sharing leadership and decision-making space (Derrien et al., 2019). While partnerships are an inherent part of the way public land management agencies accomplish work, partnering requires agency investment and a commitment to new ways of working. Collaborative partnerships build trust and enduring relations between agencies and communities (Coleman et al. 2018). Partnering enables natural resource agencies and the communities they serve to develop flexible, innovative strategies to address shared conservation concerns (Armitage et al. 2009). Collaborative governance is a critical component of sustainable recreation management on public lands (Selin et al. 2020).

Partner organizations bring both volunteer labor and technical expertise to projects that can complement or enhance federal agency capacity (Seekamp et al. 2011). Trail organizations with a healthy volunteer base are essential to the long-term success of NSTs. In 2019, 29 trail organizations engaged 22,224 volunteers who collectively contributed nearly 1 million hours. Trail organizations also raised $14.3 million in private monetary contributions (Partnership for the National Trails System 2019). Trail organizations rely on a cadre of committed volunteers with a wide range of skills. Volunteers may be motivated by a desire to enhance natural resource management, to contribute to society, to connect with a treasured place, or to interact with like-minded people (Lu and Schuett 2014; Bruyere and Rappe 2007; Martinez and McMullin 2004).

Environmental volunteers gain many benefits, including physical activity, stress reduction, social integration, nature connection, and bonding with place. Nationally, volunteer rates have declined steadily since the early 2000s. In 2003, 28.8 percent of Americans volunteered compared to 24.9 percent in 2015, though the number of volunteer hours held steady (Grimm and Dietz 2018). For some NST partners, volunteerism is flat or declining. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy reported 6,827 volunteers (272,477 hours) in 2015, compared to 5,967 volunteers (210,923 hours) in 2019 (Joyner 2019). With these trends in mind, understanding the long-term viability of the volunteer workforce will be critical to the success of NSTs (McPadden and Margerum 2014).

Understanding Partnerships

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 14 key informants to learn more about the role of partners in NST stewardship. Included in our group of experts were NST trail administrators (7), representatives of NST partner organizations (3), national trail organizations (1), and other federal agency employees (3). We asked key informants to describe the historic role of trail partners, current issues and challenges on NSTs, specific concerns related to NSTs in wilderness areas, the current role of trail partnerships, benefits and challenges of trail partnerships, and ideal models of NST stewardship.

Relationships and Roles among NST Partners

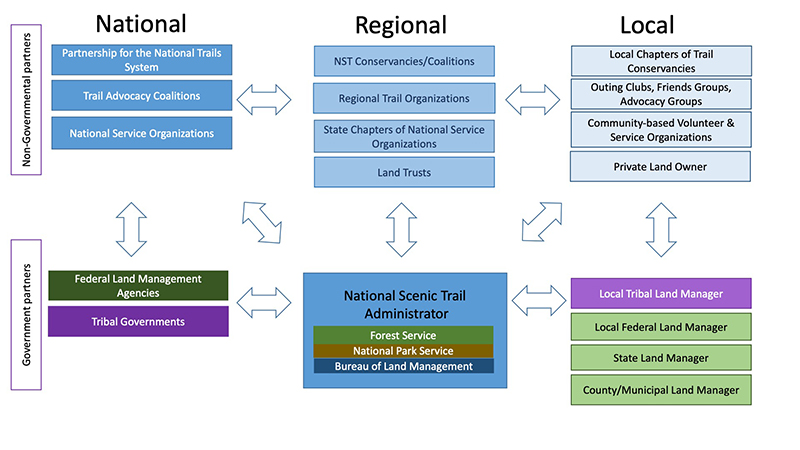

Partners have played a significant role in the development and management of trails throughout the United States and federal agencies increasingly rely on partners for aspects of trail maintenance, management, and operations (McPadden and Margerum 2014; Shaffer 2016). The Partnership for the National Trails System (PNTS) connects 34 member trail organizations supporting each of the NSTs to further the protection, completion, and stewardship of national trails. Federal agency administrators rely on the PNTS and its member trail organizations (e.g., trail conservancies, trail coalitions) for all aspects of trail planning, management, and maintenance. These NST organizations coordinate with regional trail organizations and their local chapters to maintain trails in their region. NST organizations also work with (and sometimes function as) land trusts – acquiring lands and conservation or trail easements that connect missing trail links, or that otherwise protect the trail corridor. National service organizations like the Student Conservation Association, Job Corp, or Veterans Conservation Corp, conduct trail work while also achieving goals like job training or leadership development. Local trail-based groups also maintain trail segments in their area (e.g., adopt-a-trail programs, outing clubs, or “friends of” groups) and may work with community-based organizations on an ad hoc basis (e.g., scouting groups, schools, religious organizations). Some groups offer specialized trail expertise, such as the Back Country Horsemen of America, whose members provide support for trail building in remote areas using pack animals (particularly in designated wilderness areas). Many other entities play a critical role in the management of NSTs in the system, including tribes and state agencies. Figure 1 depicts partners at the national, regional and local level oriented toward stewardship of NSTs.

Figure 1 – Depiction of governmental and NGO trail partners at the national, regional, and local scale for National Scenic Trails. (Note: This is meant to be representational and not exhaustive of the full array of trail partners and their interactions.)

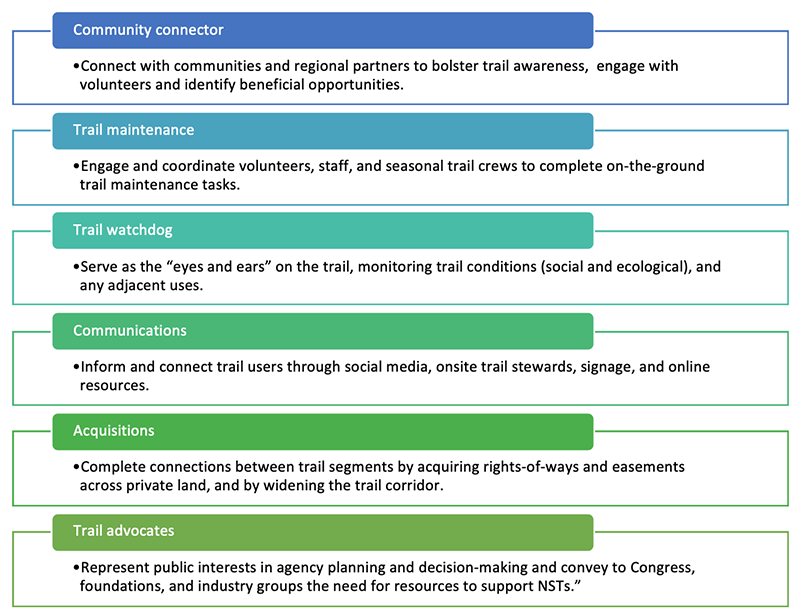

NST designation can prompt new or existing organizations to coalesce and formalize their roles around trail management. Our interviews with trail administrators and trail partners revealed a variety of roles for trail partners, many of which are overlapping and ever-evolving (Figure 2). We identified six critical roles for NST partners: community connector, trail maintenance, trail watchdog, communication, acquisitions, and trail advocates.

Balancing these various roles, while navigating relationships among trail administrators, other state and federal agencies and cooperating partners can prove challenging for trail partners.

Benefits and Challenges of Partnering

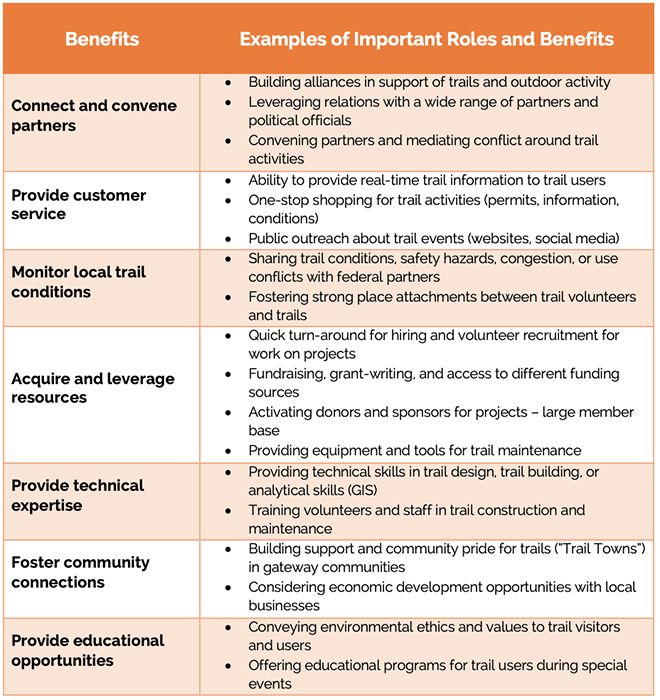

Shared stewardship is an approach that recognizes that the collective capacity of multiple organizations with shared interests can be a powerful influence on our ability to care for our natural and cultural heritage (Derrien et al. 2019). Previous studies about the benefits of natural resource partnerships have noted the ability to leverage resources, add new skills and expertise, and provide opportunities for citizen engagement (Seekamp et al. 2013; Absher 2010). We asked our key informants to describe the benefits of NST partnerships (Table 1). NST partnerships provide a number of important benefits from the perspective of federal partners. They can build alliances and connect with local partners, provide customer service, monitor real-time trail conditions, mobilize resources efficiently, offer technical expertise, foster community relations, and provide educational opportunities.

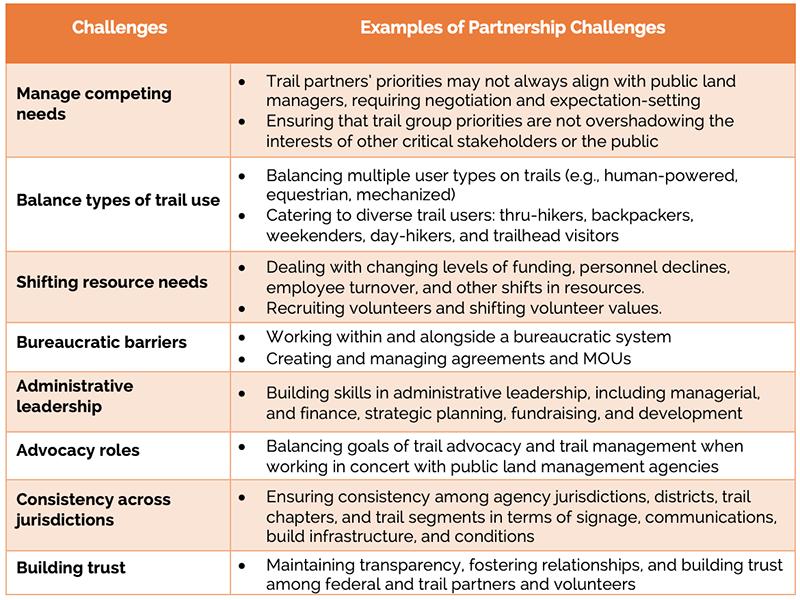

Partnerships also can present challenges, particularly as organizations change or expand their mission and agencies face shifts in capacity. Like any relationship, partnerships take work and require resources. Some of the greatest challenges associated with natural resource partnerships include burnout, severed relationships from employee turnover, lack of staff to maintain partnerships, administrative barriers, and a mismatch of goals (Seekamp et al. 2013). Our key informants identified some of the challenges of partnerships for NSTs (Table 2). Many of these challenges identified echoed previous studies, particularly related to declines in capacity, shifting resources, and overcoming bureaucratic barriers (Seekamp et al. 2013; Absher 2010). One element unique to NST partnerships is the transformation of trail organizations associated with trail designation. NSTs often are promted by passionate trail enthusiasts whose early work has led to trail designation. As visibility expands and use grows, trail organizations must grow accordingly and develop new skills in administrative leadership and finances to maintain a critical role.

As our key informants described, challenges emerge when trail organizations have different values or priorities for trail use from federal partners. For example, a trail organization may cater to a constituency of hikers or a sub-group of thru-hikers, while federal trail administrators are concerned with a full range of trail uses. Negotiating various interests and being transparent about intent are both critical to shared stewardship enterprises.

Emerging and Ongoing Issues in NST Stewardship

Environmental Changes

Changes in climate and forest conditions have created challenges for management of NSTs. Wildfire, particularly in the US’s western states, has led to temporary trail closures due to fire risk and smoke, creating safety concerns and causing hikers to re-route. Trail organizations have served an important role alerting hikers to fire danger through social media applications and other services. Changing weather and climate patterns also have resulted in storm damage leading to washouts, flooding, landslides, avalanches and other effects that have caused damage to trails and trail infrastructure, such as bridges. These conditions are often exacerbated in post-fire environments (Brown 2018). Trail organizations have been critical in organizing volunteers to assess, document, and share trail condition data immediately following these events, to inform appropriate agency responses. Public agencies managing the trail are taxed by these events, and they often contribute to growing backlog in maintenance. Trail organizations and federal agencies work together to prioritize repair to damaged trail sections, address safety concerns, and mobilize resources to repair trail resources.

Increasing trail use and ecological effects

Some NSTs have experienced a steady increase in visitors as evidenced by trip reports and statistics gathered by trail organizations and administrators. The uptick in trail use has been documented on the “Triple Crown” Trails (Reigner and Wimpey 2020). The increased use of NSTs by long-distance “thru-hikers” and other trail users raises questions about social-ecological conditions along the trail. Heavy use on trails designed for lower levels of use can result in erosion or trail damage, trampling of vegetation, increased human waste, and greater frequency of human-wildlife interactions (Oliver 2018). Side-by-side walking and passing slower hikers can lead to trail widening, as can trampling caused by camping close to trails (Wimpey and Marion 2010). However, contrary to generalizations, visitors have been found to disperse more at low levels of visitor use, rather than when use is high (D’Antonio and Monz 2016). Additionally, activity type and trail design have been found to best predict trail impacts rather than the amount of use (Beeco et al., 2013). Growth in NST visitation puts pressure on trail organizations, administrating agencies, and volunteers to maintain healthy trail conditions to keep up with demand.

Technology and behavior altering use patterns

Use of mobile applications, GPS devices, and social media sites is changing the way some hikers interact with NSTs and with each other (Dustin et al. 2019; Martin and Blackwell 2016; Pohl 2016). Notably, interviewees revealed an emerging phenomenon for thru-hikers who coalesce in large groups, potentially concentrating camping impacts along the trail. Arrendondo (2018) referred to this as the ‘bubble effect’. Mobile phone applications and social media sites designed to help trail hikers may inadvertently concentrate visitors along a string of high-use sites with desired amenities like flat ground, fresh water, or natural shelter. According to informants, clustering can occur because of social benefits (company along the trail), perceived safety concerns (desire to camp in groups), or the timed visits of “trail angels” who provide rides or other services. This behavior can alter the social character of NSTs and decrease opportunities for solitude.

New trends in thru-hiking may also exacerbate these conditions. Ultra-lite or fast-paced hikers and trail runners may travel from pre-dawn hours to late evening. Some are known to camp close to the trail’s edge, in contrast to the footprint of the traditional backpacker. Finally, GPS devices may alter patterns of trail use, potentially encouraging off-trail travel, particularly in snow-covered conditions or in areas lacking dense vegetation, dispersing trail users across a wider swath along the trail corridor. Visitor behavior, such as the bubble effect or off-trail travel, may intensify human impacts more so than the sheer volume of visitation.

Balancing wilderness values

Our respondents described challenges in balancing increased trail use in wilderness areas with the need to preserve wilderness character. The National Trail System is managed for purposes of expanding opportunities for people to connect with nature, scenery, and heritage (P.L. 90-543). However, an essential tenet of wilderness management is to preserve opportunities for solitude and primitive recreation (Landres et al. 2008; Engebretson and Hall 2019) and large group use is regulated in designated wilderness areas. One public official we interviewed had observed groups of up to 50 hikers camped together in a wilderness area along one NST. The clustering of hikers raises questions about whether wilderness values are being diminished by the NST. Rising visitor volumes on some NSTs can present challenges for management of designated wilderness areas that lie along these trails. Research has shown that low visitation density is an important attribute associated with wilderness character (Watson et al. 2015). Encountering large groups along the trail can negatively impact hikers seeking solitude, especially in wilderness areas, although this effect was found to be small on some of the most highly used wilderness trails (Cole and Hall 2010).

Declining agency capacity

The increasing reliance on the technical skills, coordination, and availability of contracted and volunteer workforces to construct and maintain trails is a major trend in shared stewardship for NSTs. When the National Trails System Act was passed, it was common for federal land management units to employ year-round or seasonal trail crews with highly specialized skills in trail design, construction, and maintenance. Public agency declines in the budgetary, personnel, and technical capacity for outdoor recreation management have contributed to reductions in skilled workers and equipment for trail work (Cerveny et al. 2020). Trail organizations, partners, and volunteers have filled important roles to attenuate these changes in agency capacity.

Additionally, there is a need for training and certifications in advanced trail skills, which partner organizations can fill if federal agency requirements can be navigated. Some efficiencies can be achieved through agreements to recognize safety certifications across different agencies, such as sawyer certifications.

According to key informants, this shift in responsibility of trail maintenance from federal agencies to trail organizations has put added pressure on these groups, which rely on volunteer hours and donations. Trail organizations also face capacity challenges with greater needs for funding and access to volunteers. Some interviewees described concerns about the aging of their members and volunteers and the need to attract new donors and volunteers to their ranks. Research has shown that volunteer burnout, aging of the volunteer base, and lack of succession planning can affect long-term partner relations (Hvenegaard and Perkins 2019; Absher 2010). Thus, land management agencies and partners benefit from leveraging existing capacity and expertise to ensure new generations of trail stewards (McPadden and Margerum 2014).

Stewardship Challenges in Wilderness

Trail design, construction, and maintenance of NSTs in wilderness areas can be challenging, especially when trails were built prior to the creation of modern sustainable trail construction guidelines (Marion et al. 2011). Several key informants noted that wilderness areas and other remote trail sections can be difficult for trail crews to access and require more costly and complicated solutions. Trail crews must be available for multiple days or weeks to make efficient use of time and sometimes require special training or means of travel (pack animals, canoe access). The prohibition of motorized equipment (required for wilderness and other special areas) can make work more difficult, especially when trail crews have not been adequately trained in use of cross-cut saws. Sections of NSTs that pass through wilderness areas can be challenging to build and maintain and damages from landslides, floods, or windfall can pose safety hazards when not addressed promptly. Improvements might be made through increased trail crew capacity, trail crew training, and education programming for visitors.

Managing Multiple User Types across Jurisdictions

Managing uses along the length of an NST can be difficult, as different uses are permitted based on land ownership, the agency’s management approach, special land use designations, or other factors. Several interviewees raised the issue of consistency of management over sections of NSTs crossing multiple jurisdictions. Some NSTs (and trail sections) are open to various uses, including equestrian or bicycles; and, some trail sections are along public roads allowing motorized vehicles. Some trail segments traverse sections hosting incompatible activities, such as logging or target shooting. Although not every trail is open to every use in all segments, local land managers aim to balance use consistent with their individual management objectives and work with trail organizations and other partners to provide opportunities for different types of trail uses. Multiple uses can also result in social issues when a user group’s values come in conflict, or when groups compete for the same space (Manning et al. 2017).

NSTs are designed to welcome a variety of trail users and are managed to encourage visitor connection to our nation’s natural and cultural heritage. While motorized use on NSTs is typically prohibited, with the exception of trail segments that exist along public roads, equestrian trail use does provide access to NSTs that may not be otherwise possible for some trail users. Thus, equity, access and inclusion are important considerations for federal trail administrators.

Partnerships to Complete Trails

While some NSTs are complete, others include segments that are unfinished or are adjacent to lands that are not protected from development or uses that threaten the character of the trail. Trail organizations and agency administrators are actively working to engage with public and private landowners to create easements, purchase land, or develop agreements to provide a trail experience that is safe and that maximizes the trail opportunities. For many trails, there are substantial sections that exist along roads and highways that present safety concerns. Meanwhile, despite the inevitable need to cross motorized roads, motorized use is in conflict with the National Trails System Act. Trail partners serve an important role in raising awareness of the trail and its value to the region in areas with unfinished trail segments. Cultivating relationships with tribal, county, state and private entities who may become trail supporters, can help foster local support toward trail connection and completion. Sharing resources in outreach and communication is an important element in trail stewardship.

Community Connections

While thru-hikers may hold a place in the popular imagination, the majority of NST visitors are day visitors, short-term backpackers (who may utilize trail segments), and trail section hikers seeking to complete a portion of the trail. The Appalachian Trail, for example, receives an estimated 3 million trail visitors annually, compared to 3,000 who attempt the entire 2,190 miles (Appalachian Trail Conservancy 2020). For some, visiting the trailhead provides a meaningful experience to connect with the legacy of an iconic trail. NSTs and trail connectors provide an important means for nearby communities to connect with the outdoors, enhancing health benefits associated with being outdoors. Trail administrators and partners increasingly recognize the importance of connecting with community leaders, business owners, and economic development entities in gateway communities. In recent years, “trail town” programs have emerged, which link communities with NSTs and emphasize the importance of community awareness and pride. Partnerships with gateway communities can help build community support for the trail, related projects and events, marketing, and fundraising for trail management. Many trails connect with local communities through youth corps programs, providing opportunities for youth to experience and engage with public lands. Stewardship is being understood as a form of recreation that strengthens ties between communities and special places (Miller et al. 2020).

Future Visions

“There is something special that comes from the language in the Act and the history that it draws… the idea of true shared stewardship and co-management and that notion that everyone is trying to partner.” — Trail Administrator (paraphrase)

Many land managers and partners view NST partnerships as the original and ideal model for shared stewardship. From the conception of trails to their designation and management, these national trails build on a public passion for trails that is channeled and orchestrated into effective working partnerships among private and public institutions. While these partnerships vary in how they are organized and staffed, they all demonstrate a joint investment in stewarding shared public resources. This idea of shared stewardship is at the heart of current land management agency approaches to stewarding natural and cultural resources. The partnership structures, investments, and networks for NSTs deserve agency attention as an effective case study and model for engaging in meaningful work with others. They offer important insights for shared stewardship for other recreation resources, as well as in other management areas, such as wildfire and cultural landscapes. We asked each interviewee to describe their vision of the ideal NST stewardship model. There was a consensus among interviewees, who described a governance model with a central, primary trail organization with ties to dozens of stakeholders and partners, akin to the umbrella organization model described earlier (Seekamp et al. 2011). In this model, the central partner has a high capacity for administrative functioning and the flexibility to develop and manage websites, maintain a social media presence, keep maps updated and available, and communicate directly with trail visitors. This central partner creates a network with its local chapters to share local, on-the-ground knowledge, which it imparted to trail users in a timely manner and used to identify and prioritize maintenance needs. And, it is connected with nearby communities to build relationships and encourage local engagement. In this suggested ideal model, strong working relationships among agency staff and NGO partners are critical, and maintaining sufficient agency staff with local knowledge is necessary, particularly during planning periods. As shown in Figure 2, these multiple roles are important for trail organizations, and they cannot perform these functions without sufficient agency engagement and support, as well as engagement from other trail partners.

Partnerships draw on organizational strengths (such as nimbleness and efficiencies with funding, staffing, and volunteers), and on the strength of networks that are deeply attuned to local conditions. While challenges persist for these partnerships, and adjustments and refinements are needed to improve the model, many are champions of the model itself. The National Trail System was the original model for shared stewardship. Because it is legislated that partnerships are integral to trail management, NSTs can be laboratories for trying new ways to partner and showcasing partnership success. As natural resource agencies lean toward greater emphasis on co-management and shared stewardship of our treasures in natural and cultural heritage, we can learn from the lessons of NSTs.

About the Authors

LEE CERVENY is a research social scientist and Team Leader for the People and Natural Resources Team, USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station; email: lee.cerveny@usda.gov

MONIKA DERRIEN is a research social scientist with the USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station.

ANNA MILLER is the assistant director of Research and Operations at the Institute of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism at Utah State University.

References

Absher, J. D. 2010. Partnerships and volunteers in the US Forest Service. In: Klenosky, David B.; Fisher, Cherie LeBlanc, eds. Proceedings of the 2008 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium; 2008 March 30-April 1; Bolton Landing, NY. Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-P-42. Newtown Square, PA: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: 110-114. 2009.

Ansell, C, and A. Gash. 2007. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18(4): 543–571

Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) 2020. https://appalachiantrail.org/explore

Armitage, D. R. ,R. Plummer, F. Berkes, R. I. Arthur, A. T. Charles, I. J. Davidson-Hunt, A. P. Diduck, N. C. Doubleday, D. S. Johnson, M. Marschke, M. and P. McConney. 2009. Adaptive co‐management for social–ecological complexity. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 7(2): 95-102.

Arrendondo, J. R. 2018. Modeling areal measures of campsite impacts on the Appalachian National Scenic Trail, USA using airborne LiDAR and field collected data (Master Thesis). Retrieved from Virginia Tech Electronic Theses and Dissertations. (2018-07-24T20:01:05Z

Beeco, J. A., J. C. Hallo,. and G. W. Giumetti. 2013. The importance of spatial nested data in understanding the relationship between visitor use and landscape impacts. Applied Geography 45: 147-157.

Berkes, F. 2009. Evolution of co-management: role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. Journal of Environmental Management 90(5): 1692-1702.

Brown, M. 2018. Fire and Ice: The Pacific Crest Trail in the era of climate change. Sierra Magazine. https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/fire-and-ice-pacific-crest-trail-era-climate-change

Bruyere, B. and S. Rappe. 2007. Identifying the motivations of environmental volunteers. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 50(4): 503-516.

Cerveny, L. K., N. Meier, S. Selin, D. J. Blahna, J. Barborak, and S. McCool. 2020. Agency capacity for effective outdoor recreation and tourism management. In. Selin, S., Blahna, D. and A. Miller, Eds. Igniting the science of recreation: linking science, policy, and action. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-978. Portland, OR: U.S. Depart¬ment of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. Pp.

Cole, D. N., and T. E. Hall. 2010. Privacy functions and wilderness recreation: use density and length of stay effects on experience. Ecopsychology 2(2): 67-75.

Coleman, K., M. J. Stern, and J. Widmer. 2018. Facilitation, coordination, and trust in landscape-level forest restoration. Journal of Forestry 116(1): 41-46.

D’Antionio, A., and C. Monz. 2016. Visitor use levels on visitor spatial behavior in off-trail areas of dispersed recreation use. Journal of Environmental Management 170: 79-87.

Derrien, M .M., L.K. Cerveny, M. Martin, and M. Arnn. 2019. To share and sustain: Stewarding recreation resources in the U.S. Forest Service. Forestry Source 24(7): 5, 13, 18.

Dustin, D. K. Amerson, J. Rose, and A. Lepp. 2019. The cognitive costs of distracted hiking. International Journal of Wilderness 25(3); 12-23. https://ijw.org/cognitive-costs-distracted-hiking/

Engebretson, J.M., and T. E. Hall. 2019. The historical meaning of “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation” in the Wilderness Act of 1964. International Journal of Wilderness 25(2): 10-31. https://ijw.org/historical-meaning-in-wilderness-act/

Grimm, R. T., Jr., and N. Dietz, N. 2018. “Where are america’s volunteers? A look at america’s widespread decline in volunteering in cities and states.” Research Brief: Do Good Institute, University of Maryland.

Hvenegaard, G.T., and R. Perkins. 2019. Motivations, commitment, and turnover of bluebird trail managers. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 24(3): 250-266.

Joyner, L. 2019. Volunteer numbers hold steady while hours on the rise. Appalachian Trail Conservancy. http://www.appalachiantrail.org/home/volunteer/the-register-blog/the-register/2019/11/05/volunteer-numbers-hold-steady-while-hours-on-the-rise

Koehler, B. and T. M. Koontz. 2008. Citizen participation in collaborative watershed partnerships. Environmental Management 41(2):143.

Koontz, T. M., T. A. Steelman, J. Carmin, K. S. Korfmacher, C. Moseley, and C. W. Thomas. 2004. Collaborative environmental management: What roles for government? Washington,DC: Resources for the Future

Landres, P., C. Barns, J. G. Dennis, T. Devine, P. Geissler, C. S. McCasland, L. Merigliano, J. Seastrand, and R. Swain.2008. Keeping it wild: an interagency strategy to monitor trends in wilderness character across the National Wilderness Preservation System. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-212. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 77 p., 212.

Lewis, G. B. and Y. J. Cho. 2011. The aging of the state government workforce: Trends and implications. The American Review of Public Administration 41(1): 48-60.

Lu, J. and M. A. Schuett. 2014. Examining the relationship between motivation, enduring involvement and volunteer experience: The case of outdoor recreation voluntary associations. Leisure Sciences 36(1): 68-87.

Manning, R.E., Anderson, L.E., Pettengill, PR. 2017. Managing outdoor recreation: Case studies in the national parks (2nd ed.). CABI Publishing.

Marion, J. L., J.F. Wimpey, and L. O. Park. 2011. The science of trail surveys: Recreation ecology provides new recreation ecology provides new tools for managing wilderness trails tools for managing wilderness trails. Park Science 28(3): 60-65.

Martin, S., and J. Blackwell. 2016. Influences of personal locator beacons on wilderness visitor behavior. International Journal of Wilderness 22(1): 25–31.

Martinez, T. A. and S. L. McMullin. 2004. Factors affecting decisions to volunteer in nongovernmental organizations. Environment and Behavior 36(1):112-126.

McPadden, R., & R. D. Margerum. 2014. Improving National Park Service and nonprofit partnerships—Lessons from the National Trail System. Society & Natural Resources 27(12): 1321-1330. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2014.970738

Miller, A. B., L. R. Larson, J. Wimpey, and N. Reigner. 2020. Outdoor recreation and environmental stewardship: The sustainable symbiosis. Igniting research for outdoor recreation: linking science, policy, and action. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-987. Portland, OR: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, pp.227-244.

National Forest Foundation 2005. Partnership guide. US Forest Service. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5193234.pdf

National Trails System Act of 1968, 16 U.S.C. §§ 1241–1251, Public Law 90-543 (1968).

Oliver, J. 2018. Fixing the Appalachian Trail’s overcrowding crisis. Outside Magazine. https://www.outsideonline.com/2293166/can-ridgerunners-fight-appalachian-trail-overcrowding

Partnership for the National Trail System (PNTS). 2019. Gold Sheet: Contributions made in 2019 to support the National Trails System by national scenic and historic trails organizations.

Pohl, S. 2006. Technology and the wilderness experience. Environmental Ethics 28: 147–163.

Reigner, N. and J. Wimpey. 2020. Multi-jurisdictional collaborative management of the Pacific Crest National Scenic and John Muir Trails. International Journal of Wilderness 26(2).

Seekamp, E., L. A. Barrow,. And L. K. Cerveny. 2013. The growing phenomenon of partnerships: A survey of personnel perceptions. Journal of Forestry 111(6): 412-419.

Seekamp, E., L. K. Cerveny, & A. McCreary 2011. Institutional, individual, and socio-cultural domains of partnerships: A typology of USDA Forest Service recreation partners. Environmental Management 48(3): 615-630.

Seekamp, E., & L. K. Cerveny. 2010. Examining USDA Forest Service recreation partnerships: institutional and relational interactions. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 28(4).

Selin, S., D. J. Blahna, and L. K. Cerveny. 2020. How can collaboration contribute to sustainable recreation management. Igniting research for outdoor recreation: linking science, policy, and action. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-987. Portland, OR: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, pp.203-211.

Shaffer, D. 2016. Connecting humans and nature: The Appalachian Trail Landscape Conservation Initiative. The George Wright Forum 33(2): 175-184.

USDA Forest Service. 2014. National Scenic and Historic Trails Program. 16 p. Accessed at https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprd3855600.pdf

Watson, A., S. Martin, N. Christensen, G. Fauth, and D. Williams. 2015. The relationship between perceptions of wilderness character and attitudes toward management intervention to adapt biophysical resources to a changing climate and nature restoration at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Environmental Management 56: 653-663.

Wilderness Act of 1964, 16 U.S.C. 1131-1136, Public Law 88-577 (1964)

Wimpey, J. F, and J. L. Marion. 2010. The influence of use, environmental and managerial factors on the width of recreational trails. Journal of Environmental Management 91: 2028-2037

Read Next

Foundation and Future of Long Distance Trails

We begin this special edition of the International Journal of Wilderness with references to the U.S. Wilderness and National Trails System Acts to illustrate the significance and interconnectedness of wilderness areas and long-distance trails.

With Collaboration We Can Overcome Challenges Together

The concepts of “shared stewardship” or “collaborative management” can be challenging. They require shared vision, definition of clear roles and responsibilities, and commitment to the collaborative process.

Multi-jurisdictional collaborative management of the Pacific Crest, National Scenic, and John Muir Trails

Information about visitor use in parks and protected areas is an essential component of effective management.