The Kelso Valley on the Pacific Crest Trail. Photo credit © Ryan Weidert

With Collaboration We Can Overcome Challenges Together

Soul of the Wilderness

August 2020 | Volume 26, Number 2

In my thirty years working in the wilderness and trails community, I have seen some of the best examples of wilderness stewardship and collaboration. At the heart of this, are core values of protection for special places, including National Scenic Trails (NSTs) and wilderness areas through which they run, and shared stewardship based on collaboration, science, and the complimentary purposes of NSTs and wilderness preservation. These values shape the missions and responsibilities of land managers, scientists, volunteers, and partners in order to create a robust community that will ensure that these lands, and their natural and cultural resources, are protected in perpetuity. The Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail (PCT) travels through 48 US federally designated wilderness areas. With over half the mileage of the PCT traversing designated wilderness, Clinton Clarke (Figure 1), founder of the Pacific Crest Trail Conference in1932, shared that the conference’s mission was “to maintain and defend for the benefit and enjoyment of nature lovers the Pacific Crest Trailway as a primitive wilderness pathway in an environment of solitude, free from the sights and sounds of a mechanically disturbed nature” (Clark, 1945).

The concepts of “shared stewardship” or “collaborative management” can be challenging. They require shared vision, definition of clear roles and responsibilities, and commitment to the collaborative process. Efforts can quickly dissolve if trust is broken or if partners are asked to contribute in ways that do not meet their core interest. Collaboration takes more time than independent management. That’s worth repeating – to successfully collaborate, it takes a lot more time! Brian O’Neill, Park Superintendent for the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (deceased), set the gold standard for partnerships. His twenty-one best practices (O’Neill n.d.) (Figure 2 are sprinkled with jewels such as “Find Ways through Red Tape” and “Strive for Excellence.”

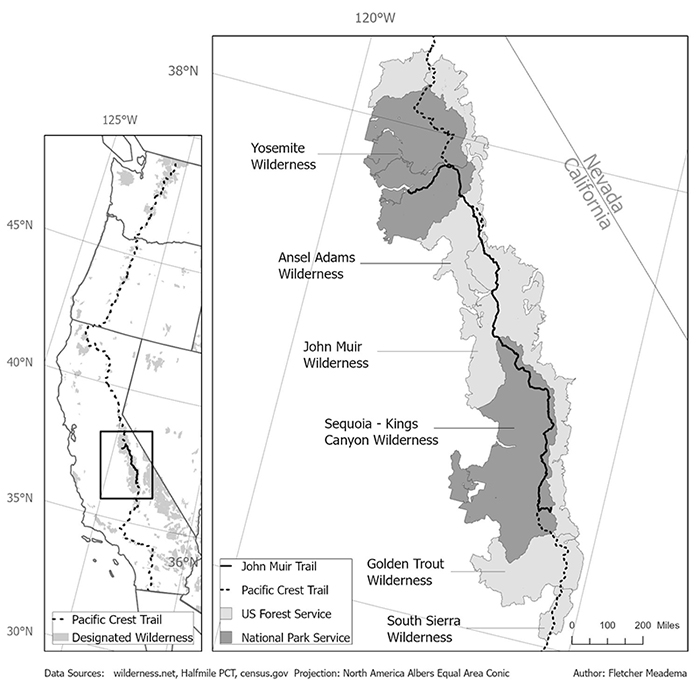

Superintendent O’Neil’s partnership work articulates the guiding principles of a California-based collaborative effort I’m currently facilitating in the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains where the Pacific Crest Trail and John Muir Trail overlap (PCT/JMT). The PCT/JMT collaborative is an ad hoc group of NST and wilderness agency managers, researchers, and management partners who have joined together to realize a shared vision – “The Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail and the John Muir Trail, while preserving and protecting the Wilderness lands they traverse, provide outstanding long-distance hiking and equestrian opportunities across multiple agency boundaries through the iconic high Sierra.” The collaborative group started meeting in Fall 2016 in response to unprecedented increases in backcountry travel along the 170-mile coincident path of the PCT and JMT. The trail provides a route along the wilderness heartland of the high Sierra through Yosemite, Sequoia-Kings-Canyon, South Sierra, Golden Trout, Ansel Adams, and John Muir Wildernesses (Figure 3). Visitor use management in this region is very complex due to the high levels of visitor use, multiple access points to the trail, and multiple land unit- based (i.e., national park, national forest) permit systems for managing overnight users. Without thoughtful integrated management, individual park or forest decisions can quickly result in unintended impacts to other units connected by the trail – sometimes referred metaphorically as “squeezing the toothpaste tube” to reflect that an action taken in one place (i.e., a squeeze of the tube) generates sometimes messy effects elsewhere.

Our collaborative work to create a shared vision and coordinated management requires patient cooperation that accommodates each participants’ different missions, concerns, capacities, and capabilities. Our initial work started with a facilitator, name tags, and table name tents. Over time our work has grown into a system of collaborative and coordinated engagements that have resulted in real improvement for trail and wilderness management in the Southern Sierra. To that end, the group has identified the following areas of common interest: 1) establish a collaborative partnership and shared vision; 2) manage visitor experiences/protect resource values and conditions; 3) coordinate a systematic approach to wilderness permits and quotas; and 4) develop and deliver common and effective education messages and materials. Deliberation on practical topics such as alignment of food storage requirements to protect wildlife, collection of wilderness monitoring data to provide greater benefit across units and agencies, and management consideration for locations that do not require permits but access areas that do, have led to spirited discussions, which in turn have strengthened the collaborative group and improved management at the unit, regional, and trail-wide levels.

Perhaps the greatest success of our collaborative has been to build opportunities and support systems for science-based decision making through collaborations with social scientists, recreation ecologists, and trails experts from multiple universities. Their research, leveraged through the collaborative group’s diverse experience and knowledge, provides current and near real-time information to inform discussion and management decisions. The team’s research and data focus primarily on who our visitors are, and where, when, and how visitors travel and camp. The outputs provide diverse and dynamic insights into existing conditions, trends, and knowledge gaps. The research and analysis process and engagement help to focus our management strategies to achieve our shared vision – to protect these special places and provide outstanding opportunities for long-distance travel. Many thanks to the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute and faculty at Virginia Tech, Penn State, Humboldt State, and the University of California-Merced for their insightful collaborations.

I hope you’ll be inspired by the opportunities and benefits of these type of collaborations. Our team has evolved from being a collection of strangers to a team of close-knit players who use each other’s strengths to accomplish real and good work. The tangible benefits of this collaboration are the integrated transboundary patrols (agency staff and volunteers), monitoring, mapping, and educational efforts. The conundrum of how to allocate limited staff time to this “outside” influence is a challenge we all share, but none-the-less are also called to consider in order to protect and preserve these special places. Benton Mackaye, founder of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail (Figure 4), recognized the intangible benefits of both trails and wilderness by offering: “A period recourse into the wilds is not a retreat into secret silent sanctums to escape a wicked world, it is to take breath amid effort to forge a better world.” Gratefully, with national scenic and historic trails in all fifty of the United States, we have a remarkable opportunity to link our stewardship of wild places and to create relevant and enduring partnerships across the nation.

About the Authors

BETH BOYST is the Pacific Crest Trail administrator for the US Forest Service; email: beth.boyst@usda.gov

References

Clarke, C. C. 1945. The Pacific Crest Trailway. (Pasadena: The Pacific Crest Trail System Conference, 12.

O’Neill, B. n.d. Brian O’Neill’s 21 Partnership Success Factors. Retrieved June 3, 2020 from https://www.nps.gov/subjects/partnerships/upload/BrianONeillBooklet-Edited-9-27-13-2.pdf

Read Next

Foundation and Future of Long Distance Trails

We begin this special edition of the International Journal of Wilderness with references to the U.S. Wilderness and National Trails System Acts to illustrate the significance and interconnectedness of wilderness areas and long-distance trails.

Shared Stewardship and National Scenic Trails: Building on a Legacy of Partnerships

National Scenic Trails connect people with the natural and cultural heritage of the United States. Theses trails also provide important opportunities for agencies to engage partners in trail stewardship and sponsorship.

Multi-jurisdictional collaborative management of the Pacific Crest, National Scenic, and John Muir Trails

Information about visitor use in parks and protected areas is an essential component of effective management.