Cutoff Mountain in Montana’s Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Area, lies less than 1 km from the northern boundary of Yellowstone National Park. Photo courtesy of David Kallenbach.

Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks: A Case Study of Mining Claim History in Four Adjacent National Forest Wilderness Areas

Stewardship

December 2019 | Volume 25, Number 3

According to the Wilderness Act of 1964 (16 U.S.C. § 1131 2(c), wilderness is “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Roadbuilding, off-road vehicles, use of mechanized machinery, and the construction of most buildings are banned from wilderness areas. Therefore, in some respects, wilderness has more restrictive land-use protections than national parks. Currently, the US Wilderness System comprises over 111 million acres (44,920,106 ha) in more than 803 units administered by four federal land management agencies (Wilderness Connect 2019).

The Wilderness Act was a result of political compromise (Allin 1982, 60–101). The congressional debate lasted nine years and the draft legislation underwent 65 revisions (Hubbard et al. 1998–1999). The final version banned the construction of permanent roads in wilderness areas, but the areas remained “subject to existing private rights” (16 U.S.C. §1133[c]). For example, preexisting mining claims and oil/gas leases could be exploited in national forest wilderness, although they were still subject to agency “reasonable stipulations” (16 U.S.C. §1133[d] [3]) (Glickman and Coggins 1998–1999). The act also allowed the president to authorize water and power development, including road construction (16 U.S.C. § 1133 [d] [4]), and to control fire and pests (16 U.S.C. § 1133 [d] [1]).

There was also the specification in the act that mining claims could be filed until December 31, 1983, with some exceptions (Toffenetti 1985). Mineral claims located by the end of 1983 could be worked until fully exploited under applicable bureau regulations (Hammond 1967–1968, cited in Stofko 1983). For wilderness areas, the ability to establish new mineral rights was withdrawn after 1983 (Getches 1982; Hubbard et al. 1998–1999). Such wilderness “exceptions,” whether concerning mining, roads, or development, for example, have been summarized under the category of “non-conforming but allowable uses” (Anonymous 2011, based on Gorte 1998).

The purpose of this article is to examine the Wilderness Act’s 20-year window of opportunity to create mining claims relative to four wilderness areas in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. One can ask whether these four US Forest Service (USFS) wilderness areas may have made it more awkward to mine any claims on these lands despite the windfall of having a 20-year window of opportunity in the Wilderness Act and the existing ability to grandfather in active claims.

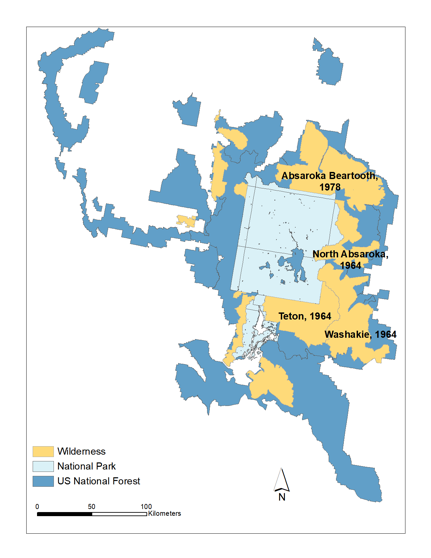

Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

The area of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), more recently called Greater Yellowstone Area, was first delineated by Craighead (1977) as representing the continuous essential habitat for the grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis). The spatial delimitation of the GYE varies based on the source. This examination utilized 73,000 square kilometers (28,185 sq. miles) as described by Glick et al. 1991 (Figure 1). This area contains two national parks (Yellowstone and Grand Teton); one national parkway (John D. Rockefeller Memorial Parkway); parts of six national forests (Bridger-Teton, Shoshone, Caribou-Targhee, Gallatin, Custer, and Beaverhead-Deerlodge); three units of the National Wildlife Refuge System (National Elk Refuge, Red Rock Lakes NWR, and Gray’s Lake NWR); one Indian Reservation (Wind River); the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Bureau of Reclamation; and state, municipal, and private lands in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho. Fully 81.7% of the land is federally owned (Glick et al. 1991) The federal agencies have given the GYE de facto recognition (Keiter 1989).

Wilderness and Mining

There are three forms of minerals on federal land: locatable (governed by the General Mining Law of 1872, as amended [30 U.S.C. §§ 22-54 and §§ 601-604]); leasable (governed by several mineral leasing acts); and salable (governed by the Material Act of 1947, 61 Stat. 681, as amended). Locatable or “hard rock” (=metallic) minerals are available to the public via claims. The locator (claimant) maintains the claim by paying an annual maintenance fee and can exploit the mineral resources after complying with the surface land management agency’s regulations. The Federal Land Protection and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA) (43 U.S.C. §§ 1701-1787) required the recordation of all federal mining claims with the BLM (Shanahan and Joscelyn 1988). It also reaffirmed the mandates in the General Mining Act of 1872 (30 U.S.C. §§ 22-42).

When first established, a claim is “unpatented,” which means that the claimant holds possessory interest in the locatable minerals. The claimant can also secure legal title by “patenting” the claim, which provides ownership of the surface land and/or the underground minerals (but in some cases, the patent may not confer full ownership of the surface). When a claim is patented, it becomes private property, but there is no federal oversight. However, the BLM has some oversight responsibility for unpatented claims (BLM, pers. comm.). When a claim has been properly located, it has a valid existing right. Except for valid claims, a periodic review by BLM determines whether the claim still has a valuable mineral deposit at the site (Ziemer 1998).

An active claim is not the same as a valuable mineral deposit (BLM, pers. comm.). An active claim is one that was approved by BLM. A valid right was properly located and maintained and has undergone a mineral evaluation indicating that an economically valuable deposit exists that could be exploited using ordinary prudence. A closed claim means that the claim has not been maintained. A closed claim is not the same as a withdrawn claim (BLM, pers. comm.). Only an active mining claim in a wilderness area can be exploited, but it need not be patented to withdraw minerals (BLM, pers. comm.). However, the most common reason for a mining claim becoming inactivated is that the owner does not renew the paperwork (BLM, pers. comm.). Fewer than 1% of claims ever become a mine (BLM, pers. comm.).

Locating a claim (i.e., location) consisted of four steps: (1) find a potentially valid claim, (2) monument the claim, (3) record it in the county courthouse, and (4) file notice with BLM (Toffenetti 1985). Generally, the USFS field offices have the authority under law and regulation to approve or disapprove the mining “plan of operations” for national forests, as well as how access is achieved (Thompson 1996; Hubbard et al. 1998–1999). USFS mining and other surface management regulations were promulgated to implement the laws governing the national forests. The USFS also actively assesses whether claims are still active. If the USFS wishes to secure a patented claim, they can offer land purchase or trades. NGOs on their own initiative may purchase them as well.

Some commentators complain that some regulations aggravate a mining initiative by making it difficult and time consuming to acquire the needed permits (Ferguson and Haggard 1973). This opinion does not stress the fact that agency resource specialists for both the BLM and USFS do all they can to present the facts, issues, and mitigation options in an unbiased fashion. Nevertheless, NGOs and others may challenge whether a claim is still active (Elliott and Metcalf 1975–1976). For more details about the BLM mining policies, see BLM (2018).

GYE Wilderness

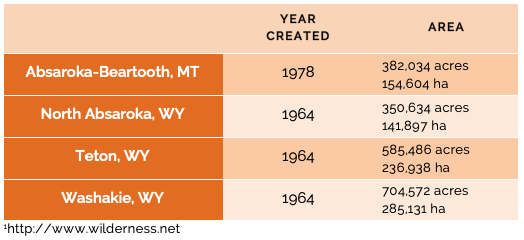

In 1972, the Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton recommended that 8,163 square kilometers (3,152 sq. miles) of Yellowstone National Park be designated as wilderness, or approximately 90% of the park, but Congress never acted on that initiative (Yellowstone National Park 2011). Regardless, due to the mandates of National Park Service (NPS) Director’s Order 41, about 95% of the park is reportedly managed as “unofficial wilderness” (White et al. 2013, 265). Official federal wilderness (USFS, US Fish and Wildlife Service [USFWS], and NPS) in the GYE constitutes 2,017,039 acres (8,600 sq. km) (USFWS 2011, 73). There are nine GYE wilderness areas, not including multiple units for one wilderness area, but the current analysis includes four that abut the two park boundaries (Figure 2). These four national forest wilderness areas abutting Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks were created from September 1964 to November 1983 (Table 1). Note that the Jedediah Smith Wilderness Area was not included because it was created in 1984 after the 20- year window closed. The Lee Metcalf Wilderness Area was not included because it was created in November 1983, one month before the 20-year window closed.

National forest nonwilderness areas are managed under a multiple-use philosophy, where mining, timber harvesting, livestock grazing, and motorized recreation is often permitted (Keiter and Froelicher 1993). Thus, mining was allowed to occur in some federal non-GYE wilderness areas (Toffenetti 1985; Ziemer 1998; Gorte 2010). The Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness, Idaho, is one example (Matthews et al. 1985). However, the reality was that the 1964 Wilderness Act, despite its many concessions to the mining industry, severely limited mining in wilderness areas due to a series of specific mandates. This generated land-use and access restrictions, surface restoration demands, and if the environmentally conscious public was aware of potential mining, negative publicity often followed (Hubbard et al. 1998–1999). The requirements of federal, state, and local pollution laws generated more restrictions (Elliott and Metcalf 1975–1976).

Approach

The distribution and influence of mining claims in the GYE was investigated using Geographic Information System (GIS) technology. The ArcGIS Desktop 10.1 (ESRI) was used to process and map data. The data on mining claims were obtained from the nondigitized BLM database LR 2000. The current analysis did not include mineral, oil, or gas leases. Data runs were made between July 2014 and May 2017. Mining claims were not determined more precisely than by the section in which they occurred. However, in the case of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Area, quarter sections were used. This approach is not precise enough to be certain whether some claims were inside or outside a wilderness boundary. To discover precise claim locations, one must first obtain the County Recorder Location Notice and amendments and then study the mapped location (BLM 2018)., A visit to the county courthouses is required, where master title plots can be examined. This task was not performed due to the large amount of time needed to do the search. Additional insights were obtained from staff mineral specialists in each national forest, BLM land law examiners, mining claims specialists, USFS and BLM geologists, GIS practitioners, and others.

Findings

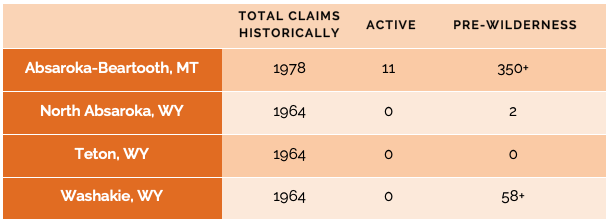

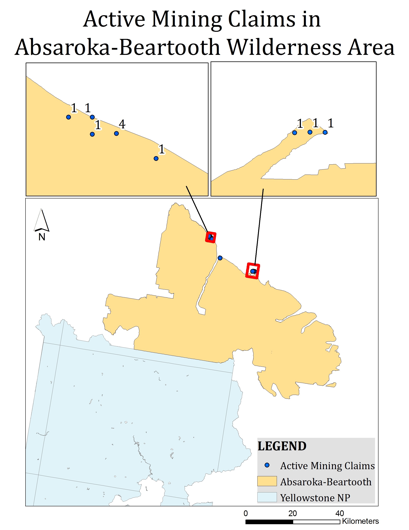

Figure 3 – The location of active mining claims in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Area as of May 18, 2017.

The current analysis involving the BLM LR2000 data revealed 11 active hard-rock mining claims as of May 18, 2017, all inside the boundaries of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Area (Figure 3) The specifics for hard-rock mining claims follow (Table 2):

This analysis indicated that the four wilderness areas harbored a minimum of hundreds of hard-rock mining claims from the early part of the 20th century until 2017. As well, at least 400 hard-rock mining claims (prewilderness claims) had the potential to be grandfathered into these four wilderness areas. Further, no prewilderness mining claims were closed before the wilderness designation.

Effect of the 20-Year Window

Figure 4 – Mining operations (background) were under way in 1999 at the McLaren Mine, New World Mining District. Heavy metal mining waste is seen in a tributary of Soda Butte Creek (foreground), 3.75 miles (6 km) northeast of Yellowstone National Park. Photo from Nimick and Cleasby 1999.

As a result of grandfathering, or the Wilderness Act 20-year window of opportunity, such rights remain in some US wilderness areas today. During the 20-year window of opportunity to stake mining claims, hundreds of claims were filed in the four GYE wilderness areas selected for this case study. Today, the number of active claims is 11, all inside the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Area. All claims are owned or controlled by one private company seeking palladium and platinum deposits. During 2018, the company was acquired by another mining company. All 11 claims were filed during the 20-year window. Further, there has been no hard-rock mining in any of these four wilderness areas, or any other wilderness areas in the GYE. The New World Mine (Dykstra 1997), although located 0.5 mile (0.8 km) from the nearest wilderness area (Figure 4) on mostly private land within the Custer National Forest, warrants mention. An NGO in 2010 purchased 772 acres (312 ha) of mining claims in the New World Mining District, the last remaining land in the district needing landscape restoration due to past mining activity.

In the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Area, 260 claims were filed during 1982 and 1983. In the last three months of 1983, approximately 70 claims were filed in all four of these GYE wilderness areas. But this number does not represent a huge increase in new claims due to the waning 20-year window of opportunity While the opportunity to grandfather in existing mining claims should have been a benefit to claims holders, and the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Area alone had roughly 350-plus claims with grandfathering potential, but claimants did not heavily utilize this window of opportunity before it expired.

After December 31, 1983, wilderness areas were no longer subject to earlier mining laws (Cwik 1983; Edwards 1986). In the case of the GYE and its USFS wilderness areas, the situation was not one of widespread claims being filed and subsequent resource extraction due to the 20-year window provided in the Wilderness Act. But this conclusion may not hold for other wilderness areas in the region or across the US Wilderness Preservation System. For example, the mining claims currently in the Cabinet Mountains Wilderness of western Montana were established during the 20-year window of opportunity, and their potential utilization and extraction has resulted in litigation (Ziemer 1998).

The US National Park System

The NPS currently has 1,010 mining claims in 15 units across the system (NPS 2017). In many of these cases, the existence of claims has been due to the grandfathering of rights. There were 6,330 active mining sites in 2004 within 20 miles of Yellowstone National Park. In this case, sites included mining claims, oil/gas leases, and geothermal locations (Napoli et al. 2004). These oil/gas and geothermal claims are arguably more threatening than hard-rock mining claims. As minerals become more valuable, the filing of claims can accelerate near park and wilderness boundaries (Pew Environment Group 2011). To thwart potential new mining claim exploitation on national forests, on October 18, 2018, then-secretary of the interior Ryan Zinke extended a 2016 2-year mineral withdrawal for another 20 years for 30, 370 acres (75,047 ha) in the Custer and Gallatin National Forests north of Yellowstone National Park. However, this will not affect existing claims on national forests or those on private land.

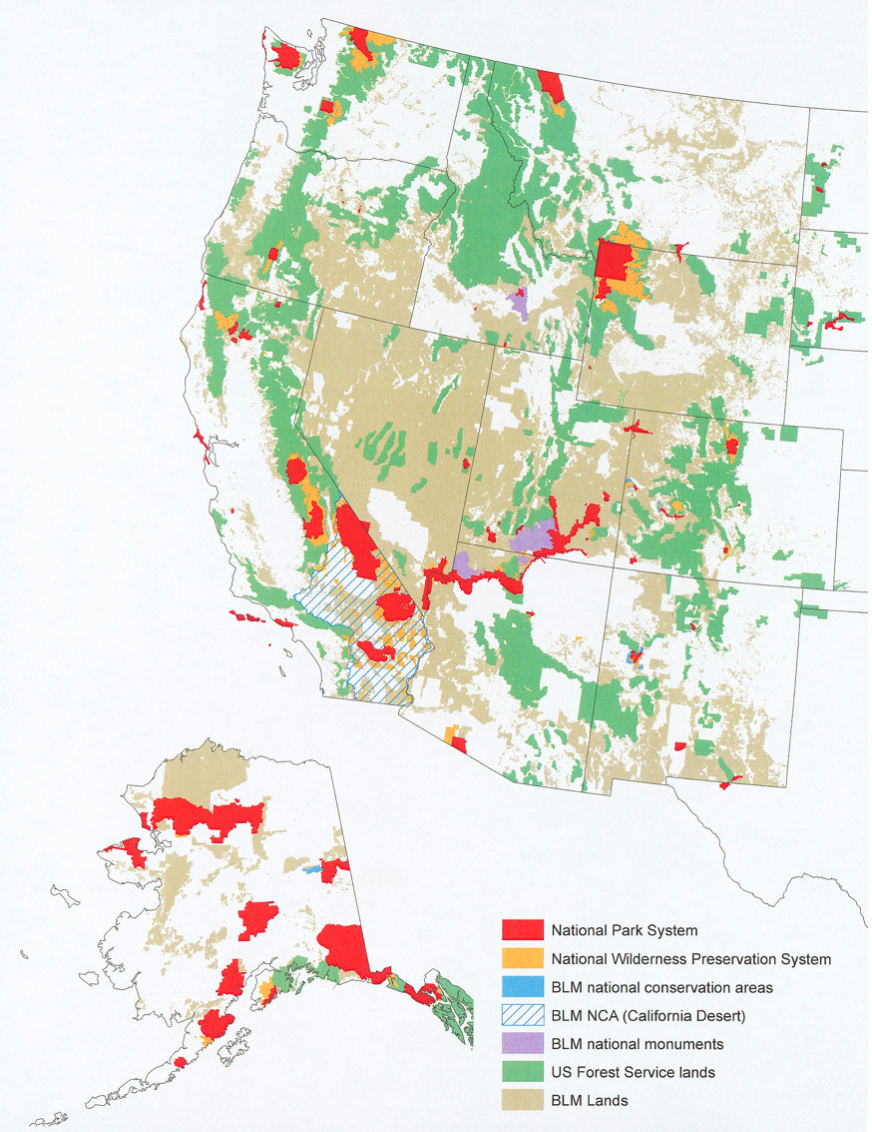

Conclusion

Toffenetti (1985, 65) said, “We will probably not know for some time whether the mining exception [the 20-year window] benefited the mining industry.” However, we know more now for some wilderness areas in the GYE, such as the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Area. Its 11 active claims were all derived from the 20-year window; none were derived from grandfathering of rights for claims existing prior to the window. But the end result of these claims has been that mining has never occurred in these four wilderness areas since designation. The New World Mine was not in a wilderness area, although it was very close to one. Future investigations could study and determine what has happened to oil and gas, and geothermal leases in these same wilderness areas. Still other studies could determine the status of wilderness hard-rock mining claims in other areas of the country (Figure 5).

Hubbard et al. (1998–1999, 599–600), has stated:

In practicality the Act severely restricted hard-rock mining activities on wilderness areas within national forests… then developing those valid claims after that date [December 31, 1983] was severely hampered by other restrictions contained in 4(d)(3) (Wilderness Act of 1964)… despite the mining industry’s hard-fought battle to win special treatment from Congress, the real issue became the extent to which regulatory agencies and courts would recognize mining rights within Wilderness Act lands. Thus it became apparent that the commercial mining interests’ hard-fought victory existed primarily on paper.

The results of this case study of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, Yellowstone, and Grand Teton National Parks, and four USFS wilderness areas that abut park boundaries, support this argument.

Acknowledgments

I thank J. Shafer, G. Varhalmi, J. Brunner, C. Schonewald, A. Greene, and three anonymous reviewers for commenting on the manuscript. A very special thanks is likewise extended to J. Li, M. Sun, and J. Yang of George Mason University, for assistance with mapping. The author is also grateful to N. Cowen, of George Washington University, for preparing Figure 4. The following people from USFS, BLM, USGS and NPS took the time to answer my many questions: V. Kelly, M. B. Marks, P. Pierson, D. Aklufi, S. Walker, J. Jones, P. Perlowitz, J. Spencer, L. Neasloney, S. Robinson, T. Williams, L. Vaeulik, M. Gonzales, K. Ostrom, T. Bakken, R. Daley, K. Long, J. Hicks, N. Arave, C. Christman, C. Lake, A. Rodriguez, G. Hurley, M. Sheer, and J. Lee. P. Stiles and G. Varhalmi of BLM and went beyond the call of duty to explain mining law, BLM databases, and BLM mining practices.

CRAIG L. SHAFER served as an ecologist with the US National Park Service for many decades. He has written widely on protected area design, planning and management. He received his PhD in Environmental Science and Policy from George Mason University in 2013; email: cshafer@gmu.edu

References

Allin, C. W. 1982. The Politics of Wilderness Preservation. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Anonymous. 2011. Wilderness Laws: Prohibited and Permitted Uses. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved July 2011 from http://www.wilderness.net/index.cfm?fuse=NWPS&sec=legiscrs.

Bureau of Land Management. 2018. Mining claim packet. Retrieved July 2019 from https://blm.gov.sites/blm.gov/files/2018_mining_claim_packet.pdf.

Craighead, J. J. 1977. A Delineation of Critical Grizzly Bear Habitat in the Yellowstone Region. Missoula: University of Montana, Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit.

Cwik, L. J. 1983. Oil and gas leasing on wilderness lands: The Federal Land Policy and Management Act, the Wilderness Act, and the United States Department of the Interior, 1981–1983. Environmental Law 14: 585–616.

Dykstra, P. 1997. Comment. Defining the mother lode: Yellowstone National Park v. the New World Mine. Ecology Law Quarterly. 24: 299–331.

Edwards, G. W. 1986. Keeping wilderness areas wild: Legal tools for management. Virginia Journal of Natural Resource. Law 6: 101–141.

Elliott, D. H., and L. C. Metcalf. 1975–1976. Closing the mining loophole in the 1964 Wilderness Act. Environmental Law 6: 469–488.

Ferguson, F. E., Jr., and J. L. Haggard. 1973. Regulation of mining law in the national forests. Land and Water Law Review 8: 391–427.

Getches, D. H. 1982. Managing the public lands: The authority of the executive to withdraw lands. Natural Resources Journal 22: 279–335.

Glick, D., M. Carr, and B. Harting. 1991. An Environmental Profile of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Bozeman, MT: Greater Yellowstone Coalition.

Glickman, R. L., and G. C. Coggins. 1998–1999. Wilderness in context. Denver University Law Review 76: 383–411.

Gorte, R. W. 1998. Wilderness Laws: Prohibited and Permitted Uses. Congressional Research Service Report 98-848.

———. 2010. Wilderness: Overview and Statistics. Congressional Research Service Report RL 31447.

Hammond, J. H. 1967–1968. The wilderness act and mining: Some proposals for conservation. Oregon Law Review 47: 447–459.

Hubbard, K. D., M. Nixon, and J. A. Smith. 1998–1999. The Wilderness Act’s impact on mining activities: Policy versus practice. Denver University Law Review 76: 591–609.

Keiter, R. L. 1989. Taking account of the ecosystem on the public domain: Law and ecology in the Greater Yellowstone Region. University of Colorado. Law Review 60: 923–1007.

Keiter, R. B., and P. H. Froelicher. 1993. Bison, brucellosis, and law in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Land and Water Law Review 28: 1–75.

Matthews, O. P., A. Haak, and K. Toffenetti. 1985. Mining and wilderness: Incompatible uses or justifiable compromise? Environment 27(3): 12–36.

Napoli, J., A. Rodman, and L. Terrill. 2004. Geological Resource Extraction in Areas Surrounding Bighorn Canyon NRA, Grand Teton National Park, and Yellowstone NP. Vital Signs Monitoring Program, Greater Yellowstone Network.

National Park Service. 2017. Mining claims. Retrieved July 2019 from https://www.nps.gov/subjects/energy/minerals/mining-claims.htm.

Nimick, D. A., and T. E. Cleashy. 1999. Quantification of Metal Loads by Tracer Injection and Synoptic Sampling in Daisy Creek and the Stillwater River, Park County, Montana. Retrieved September 2019 from pubs.usgs.gov/wri/wri004261.

Pew Environment Group. 2011. Ten Treasures at Stake: New Mining Claims Plus an Old Law Put National Parks and Forests at Risk. Washington, DC: Pew Environment Group.

Shanahan, W. A., and A. L. Joscelyn. 1988. Philosophies in collision: A perspective on FLPMA. Public Land and Resources Law Review 9: 59–79.

Stofko, M. D. 1983. A voice crying in the wilderness: Mineral exploitation rights in the wilderness under current law. Outlook Environmental Law Journal 2: 37–43.

Thompson, D. A. 1996. Mining in National Parks and Wilderness Areas: Policy, Rules, Activity. Congressional Research Service Report 96-161.

Toffenetti, K. 1985. Valid mining rights and wilderness areas. Land and Water Law Review 20(1): 31–66.

US Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Grizzly Bears (Ursus arctos horriblis) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Retrieved May 2012 from http://www.fws/mountain-prairie/species/mammals/grizzly/ Final%205YearReview_August%202011.pdf.

White, P. J., R. A. Garrott, and G. E. Plumb. 2013. The future of ecological process management.In Yellowstone’s Wildlife in Transition, ed. P. J. White, R. A. Garrott, and G. E. Plumb (pp. 255–266). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilderness Connect. 2019. Fast Facts. Retrieved September 2019 from https://wilderness.net/learn-about-wilderness/fast-facts/default.php.

Yellowstone National Park. 2011. Yellowstone Resources and Issues. Division of Interpretation, Mammoth Hot Springs, Yellowstone National Park. Retrieved April 2011 from http://www.nps.gov/yell. .

Ziemer, L. S. 1998. The 1872 mining law and the 20th century collide: A rediscovery of limits on mining rights in wilderness areas and national forests. Environmental Law. 28: 145–168.

Read Next

Young Activists: Influencing the Climate Change Movement

As 2019 closes, it is noteworthy to recognize the influence and impact of Greta Thunberg, the Swedish climate activist.

The Cognitive Costs of Distracted Hiking

What do smartphones, global positioning systems, Spot Locator Beacons, navigation apps, and other technological innovations mean for the future of outdoor recreation, and, especially, the future of wilderness?

Second Class Wilderness: Separate but Unequal Air Resources in American Wilderness

The United States has a long history throughout which equitable access to resources has been denied to segments of the population along racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic distinctions through informal, legal, and sometimes violent means.