Bandhavgarh National Park. Photo credit: © Suyash Keshari.

Wilderness Vignettes: India’s Tigers

International Perspectives

June 2023 | Volume 29, Number 1

EDITOR’S NOTE: Bandhavgarh National Park is in the heart of Central India. It is spread across 1,538 square kilometers, and has one of the highest densities of tigers in the world. It also hosts more than 40 species of mammals and 250 species of birds. Suyash spends 250+ days inside this park and has grown up in the region. He knows the landscape inside out and has a deep understanding of its wildlife. He has followed many tigers since they were just cubs, all the way to adulthood.

The Story of Tigress Solo

by Suyash Kehshari

If there is any individual that has had a decisive role to play in my personal and professional life – besides family – it has to be tigress Solo. I had known her since she was a cub herself and followed her life for almost eight years. We grew up together. Her mother was the first tiger I saw in Bandhavgarh National Park, and I followed her for nearly a decade before she passed away. I witnessed Solo overtaking her mother’s territory. I spent countless hours with her or in search of her. Through this tigress, I learned the importance of family, of living in the moment, being ruthlessly loyal and ambitious but at the same time caring and loving. I saw her miss 10, maybe 15 hunts before successfully bringing down her prey – each failed attempt bringing her closer to starvation. Through this I learned to never give up. A tigress taught me all this and more. A tigress called Solo. In October 2020, Solo was poisoned. This is her story.

Tigress Solo after the fight. Photo by Suyash Keshari.

Solo was born to Rajbehra female – a tigress famed among safari goers across the world – she was quite the showstopper at the time, controlling one of the most extensive and pristine territories in Bandhavgarh National Park. Solo and her three siblings – two females and a male – were born in 2012 in a deep cave that Rajbehra’s mother, Jhurjhura, had frequented. While Solo’s mother, Rajbehra, and grand- mother, Jhurjhura, were named after the areas they resided in, Solo got her name because of the behavior she displayed from a very young age – the tendency to be independent, venture away from her siblings in curious pursuits and be alone – being the solo female among a litter of four. As I continued to delve deeper into Solo’s life, I started recognizing her movement patterns and routines. I understood which game trails and paths she preferred most, and even which she avoided due to thorny bushes or uneven ground. I learned of her favorite waterholes, caves for resting, and trees for scent marking. All this helped me learn about her movement patterns in such detail that it became easier to predict where she would be seen next. Tigers prefer the path of least resistance and love to walk on the soft sandy safari tracks in Bandhavgarh. The game trails and pugdundees used by Solo almost always led to a road, where her pugmarks would indicate if she has passed recently or some time ago. If you are a seasoned tracker, you can easily tell if a pugmark is fresh, if it belongs to a male or female, and whether the tiger is walking, trotting, or running. Tigers are highly solitary cats and separate from their mothers within two to three years of birth. As Solo grew bigger and stronger, she pushed out her siblings to other territories and slowly captured her mother’s area – secluding Rajbehra to a small pocket of the forest where she would spend the rest of her life.

Solo and Bamera sizing each other up. Male tigers are noticeably bigger than female. Photo by Suyash Keshari.

Just as Solo was beginning to establish her dynasty, trouble ensued. Her first litter of cubs were killed within a few weeks of birth. It is unclear who fathered these cubs – much of the lives of tigers remains secret – but it was confirmed that a male named Mangu killed them. It was incredibly tragic, but in the jungles, it is about the survival of the fittest. Male tigers who do not father the cubs will kill them and mate with the female to ensure the future of their own progeny. Its nature’s brutal way of ensuring the balance. Solo’s second litter of five cubs were born in mid-2018, fathered by Mangu. One of them was born weak and passed away within two weeks of birth. After this loss and that of her first litter, Solo’s personality became more aggressive toward other tigers, and it culminated into one of the most difficult sightings of my life.

It was January 4, 2019. Solo was now about seven years old. I was in the Sehra grassland area of her territory when alarm calls of Sambhar deer alerted me to a big cat’s presence. In the distance, we saw a bulky figure approach- ing the base of a hill where Solo kept her cubs – who were just about two months old. As we approached the figure, it gave itself away as a male tiger known as Bamera Son. With his fluffy winter coat and mane in full glory, he looked bigger than ever. Though a beautiful sight, I was instantly alarmed because he was not the father of Solo’s cubs and trespass- ing in her favorite area. Within a few minutes, he picked up on Solo’s scent, and made his way toward her cave. And then everything happened with incredible speed. In an instant flash of blood and fury, Solo came thrash- ing down from the hill, almost crashing into Bamera Son, the forest around seemed to be shattering with the roaring sounds of the two tigers. It felt like the ground was shaking, and my legs began to give way in the jeep. The tigers were enveloped by thick bamboo, but the fight continued harder than ever, evident from the shaking of foliage as the two tussled about. At some point, the two separated, and Bamera Son made a dash for the road, with Solo in tow. Bamera Son’s mouth was bleeding, but what I saw next haunts me till this day – Solo, trotting behind him with her chest ripped open, skin hanging down and blood oozing out. As the two came onto the road, Bamera Son crouched down in a show of submission, bringing the fight to a decisive victory for the female, but at a massive cost. Solo continued to size him up, determined to push him away. Despite being half his size, she had somehow managed to defeat him and save her cubs. Bamera Son submitted to her once he realized that she would fight till death. My eyes were full of tears, and my hands had never felt so weak. My stomach turned, and I felt sick knowing that I could not do anything to help her. I could not interfere with nature.

Solo and Bamera. Photo by Suyash Keshari.

As Bamera Son walked away, Solo approached my vehicle – her stomach was completely empty, it looked as if she was starving – her chest flapped open, and she was bleeding from her mouth, hind legs, paws, and shoulders. I feared for her survival and that of her cubs. She came and stood just a couple meters from my jeep and gazed at me with her amber eyes as if wanting to say something. Her eyes looked full of pain and distress. That is the moment captured on this large portrait of Solo. I have seen tigers thousands of times, spent countless hours with them, and know many of them very intimately, but never had I ever felt such a boundless and inseparable connection as I felt in that moment with Solo. A day later, Solo was tranquilized by the Forest Department, and her wounds were stitched up. Solo survived. And so did her cubs. Solo was a fighter.

Tigress Solo. Photo by Suyash Keshari.

Unfortunately, this was not the end of her struggle. Solo’s territory was traversed by nine different tigers. This was highly unusual and dangerous for her well-being and the safety of her cubs. Ideally, for every four to five females, there is one dominant male that overlaps their territory, mates with them, and protects their cubs from intruding males. But our tiger reserves have become islands of paradise surrounded by an ocean of concrete, farmlands, and mines. Tigers are unable to disperse into newer habitats. If the tigers go out of the reserve, they risk running into conflicts with humans or even worse being poached or run over by speeding vehicles and trains. The remaining pockets of connecting forests are simply too narrow and deprived of food and water for the tigers to be able to disperse successfully. Solo’s problems got bigger when her chest opened back up during a difficult hunt, forcing the Forest Department to tranquilize her again to stitch her wounds – a process that is incredibly stressful for the tiger. And this process repeated itself several times. Solo grew weaker and weaker. Somehow, she was still able to provide for her cubs, as all four were quite healthy and growing at a fast pace.

Solo sleeping in pain the next day. Photo by Suyash Keshari.

Solo was in her prime, and her cubs represented the future of this troubled species, but I quickly realized that if they were to survive till adulthood, they would require more space. Bandhavgarh National Park was already overcrowded with tigers. The carrying capacity is approximately 65 tigers, but the real count was 124. In June 2020, a new female started asserting her dominance in Solo’s territory. And when the park reopened in October – after the monsoons – Solo and her cubs went missing. A search party found them two weeks later in the outskirts of the park near a small hillock bordering a village. While Solo’s cubs looked healthy as ever, she appeared quite weak and stressed – a gash healing on her shoulder was a sign of a brutal fight during the monsoons. But she was successful at protecting her cubs and keeping them healthy. Things got out of hand when she was forced to seek respite in the periphery of the park and started preying on cattle. Solo and her cubs had nowhere else to go, and nothing else to eat. Every other territory in Bandhavgarh National Park was occupied. On October 17, 2020, Solo was found dead along with two of her female cubs next to a cattle carcass. The other two went missing. One female cub was seen sometime later but she too disappeared. The male was never found. To this very day, the official reports claim that the “tigress was found dead under unnatural circumstances.” Interviews of the field guards and the veterinarian, however, point to the fact that Solo and her cubs died from poisoning of the carcass by humans, perhaps in retaliation to the cattle killings, or worse – for poaching. This news devastated me. It felt like one of the worst personal and professional losses. I had been working toward conservation in Bandhavgarh National Park with all my heart and soul. But at hearing this, I felt like giving up on everything I do. Solo came out victorious from every challenge but lost to humans. I felt completely hopeless. After a couple weeks of mourning, I summoned the courage to return to Bandhavgarh National Park to continue my work, reminding myself that there are still more tigers to protect, habitats to conserve, people to be influenced, and lives to be changed.

Rest in peace and power Solo. This is dedicated to you. And I will remain dedicated to your kind.

Communities and Conservation

by Bhavna Menon

I first visited a tiger reserve when I was 8 years old. I had bullied my family into changing the course of our holiday persuading them from visiting yet another urban destination to one in the wilderness. My first unforgettable brush with wildlife took place at the Kanha Tiger Reserve (KTR), India.

As I stood mesmerised by a herd of spotted deer grazing in the distance, I celebrated the idea of standing on hallowed land that belonged to tigers and diverse flora and fauna. At that time, I did not know much about what lay beyond the vast meadows, the foliage of the sal trees, and the charisma of the tiger itself. Forward to the winter of 2017 when I was much older (and presumably wiser). The then Field Director of KTR connected with us via The Last Wilderness Foundation (an NGO that I was then working with as their program manager) on undertaking projects in the landscape. That was when I crossed the meadows and grasslands of the forest into the homes and courtyards of the community of people who lived around the reserve.

Kanha is home to the Baiga community. The Baigas are a forest-dwelling indigenous tribal community in Central India and are recognised as a member of the Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG). The Kanha Forest Department was keen to engage with the Baigas to reduce their dependency on the forest. The tribe traditionally collected mahul (Bauhinia Vahlii) leaves from within the forest in large numbers. The leaves were used to make leaf bowls and plates which were then sold. This large-scale collection was resulting in habitat degradation as well as a possible chance of conflict of

the tribe with wildlife. Accordingly, the Forest Department wished to provide the tribe with an alternative source of livelihood.

Examples of Baiga jewellery. Photo by the Last Wilderness Foundation

It took almost a year of dialogue, numerous visits to the village, and innumerable cups of chai with the community to understand the possibilities of livelihood engagement with them. One day, as I chased some of the children around in a local game, an elderly lady from the community sat down to watch and cheer us on. I was no match for the energy of the children, and soon sat down exhausted next to her. I couldn’t help but notice a black thread around her neck with some beautiful silver coins strung on it. When I asked her, she told me that she had made the necklace, and that jewellery had always been a traditional part of the Baiga culture.

Based on the ‘mataram’s’ (mataram is a term used for elderly women or grandmothers in the village) information, we decided to arrange a meeting of the community members with the Forest Department to understand whether the community members would be keen to pursue a livelihood initiative that would provide them income as well as protect them from coming into conflict with animals. To our delight, they responded positively to the potential opportunity. Today women and men from the buffer zone villages of Kanha are significantly involved in the jewellery making process with resources provided by the Department and consequently, less dependent on the mahul leaves as a source of income. This has not only helped in maintaining the health of the forest, but has also helped in the revival of a skill set that is eco- nomically viable for the community members.

First group of Pardhi guides for the “Walk with the Pardhi’s” initiative. Photo by the Last Wilderness Foundation.

Within the same landscape but in a very different terrain, I have also had the honor to work with the Pardhis. A traditional hunt- ing community, the word ‘Paradh’ literally translates as “to hunt.” Blessed with excellent knowledge of the forests, birds and animals, the Pardhis were once used by the Maharajas and British colonizers for hunting purposes. However, as time moved forward, and the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 came into force, the Pardhi community was left behind. Once lauded for their skill sets but now viewed as criminals, the Pardhis saw little opportunity in mainstream society. They were discriminated against as ‘mere hunters’ unfit for regular jobs. As the community members continued their practice of hunting, the effects were soon evident on the health of the forests of the Panna Tiger Reserve. In 2009, tigers were declared extinct in Panna. It was at this flashpoint that the then Field Director of the reserve met with the elders of the community. He promised them education as well as a safe space for their children via hostels if they would give up their traditional weapons and hunting practices. Today, Panna boasts two hostels meant for Pardhi children. The aim is to provide the children with a quality education that will help in weaning the next generation away from a life of hunting and towards a different existence. During my time in working with the Pardhis, we were able to provide some much-needed support to the children. Today, we have our first batch of graduates who are not only looking at a bright future in our society but have become changemakers for an entire community, mobilising more and more parents to send their children to school and encouraging more families to give up hunting. Additionally, Pardhi youth in the community have eagerly grabbed at a chance for change. After much deliberation, the members of the community came up with the concept of ‘Walk with the Pardhis.’ This walk, which was the first of its kind in the landscape (initialised in association with Taj Safaris and Forest Department, Panna Tiger Reserve) utilized the amazing animal tracking and call mimicry skills of the Pardhi community members. While knowledge of the forests and flora/fauna is the main attraction, the walk allows participants a chance to understand the perspectives of the community, reduces stigma, and provides the community with a source of income. Today, via these educational and livelihood opportunities, Panna Tiger Reserve, where once tigers were declared extinct, boasts a population of 60 + tigers. In fact, the last decade has not seen a single case of tiger poaching – largely due to the efforts of the Pardhis, who now walk the forest not as hunters, but as its protectors.

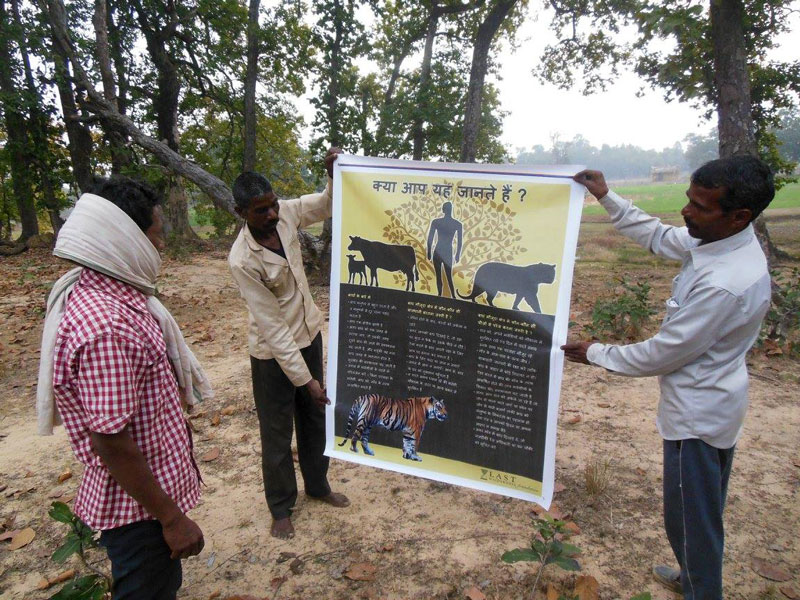

Village posters to create awareness on living safely in proximity to tigers. Photo by the Last Wilderness Foundation

On the subject of skill sets and livelihood opportunities, it was the summer of 2012 when I first visited the Damna village of the Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve. With human-wildlife conflict rife across the landscape, the community members resisted the idea of their children being taken for a tour of the reserve to view tigers via our project – The Villages Kids Awareness program. We assured the families that the children would be safe with us. The villagers decided that the only way the children would be allowed to visit was if an elder first ‘inspected’ the trip. Elder Golu Singh, 84, saw four tigers with us on his foray into the forest. As he bowed his head in reverence to the family of tigers, he also watched them move past him harmlessly. The myth of the ‘dangerous tiger’ was just broken. Golu Singh’s validation laid the foundation of our project, and we were able to engage close to 96 villages in the buffer zone of the reserve in a massive conservation outreach program that emphasised the need to protect and create a safe passage for both people and wildlife. Our project also emphasized the community’s pivotal role in protecting the last of our remaining wild spaces. During the 8-year running of the program, conflict reduced significantly. We met community members who were willing to support the idea of tiger conservation despite past incidents that had injured or killed family members. Along with an understanding of the inevitability of human-wildlife conflict, came an appreciation of how much the tiger’s forest provides in terms of day-to-day resources and livelihoods.

Today, as we celebrate 50 years of Project Tiger in India, let us take a moment to appreciate the role played by people in the tiger’s realm. Of their promise, of their engagement, of their sacrifices, and most of all, of the idea of coexistence made possible by their resilience, understanding, respect, and love for the wild. As we ask community members of the forest to respect their end of the partnership, it becomes crucial to balance the scales by accepting them for who they are, learning from their skills, and providing them the fair chance they truly deserve.

About the Authors

SUYASH KESHARI is a wildlife presenter, filmmaker, and conservationist from Central India, email: SuyashKeshari96@gmail.com.

BHAVNA MENON is a wildlife conservationist, freelance writer, and director of conservation at Aaranyachar (a wildlife tourism company in India); email: bhavna.menon1@gmail.com.

Read Next

Unseen Forces Still Wild

Between the precincts of Amun-Re and Montu in the vast Egyptian temple complex of Karnak is a dark little room permitting only a single shaft of sun- or moonlight to enter.

Kathy MacKinnon

A Smart, Dedicated, Accomplished, and Compassionate Conservationist

Can We Make Wilderness More Welcoming?

An Assessment of Barriers to Inclusion