Rafter on Lake Malbena, near Halls Island. Photo credit © Loic Auderset.

Wilderness Tourism: A Cautionary Tale from the Tasmanian Highlands

International Perspectives

December 2020 | Volume 26, Number 3

The word “wilderness” is generally associated with extensive areas of land that remain in a largely natural and undeveloped condition, but, beyond this broad consensus, there is currently no general agreement on a how wilderness should be defined (Hawes et al. 2018). After considering the range of definitions and issues, Hawes et al. (2018) propose it can be succinctly described as land that is natural, remote, and primitive (i.e., largely free of evidence of modern technological society).

Following the emergence of wilderness as a major focus of conservation debate in Australia during the 1960s, wilderness conservation became a significant motive behind the expansion of the reserve system (Mendel 2002). Tasmania, Australia’s island state, suffered a major loss of wilderness during the 20th century, despite a major increase in the area of national parks and reserves (Mendel 2002). Most of this loss related to hydroelectric development or extractive industries such as forestry and mining.

Nature-based tourism has often been promoted as assisting conservation outcomes or as a mechanism to achieve them, but tourism enterprises and wilderness are, at best, uneasy companions (Wolf et al. 2019; Kirkpatrick 2019). “Scenery mining,” as Kirkpatrick (2019) has characterized the style of modern tourism, has now emerged as a significant current threat.

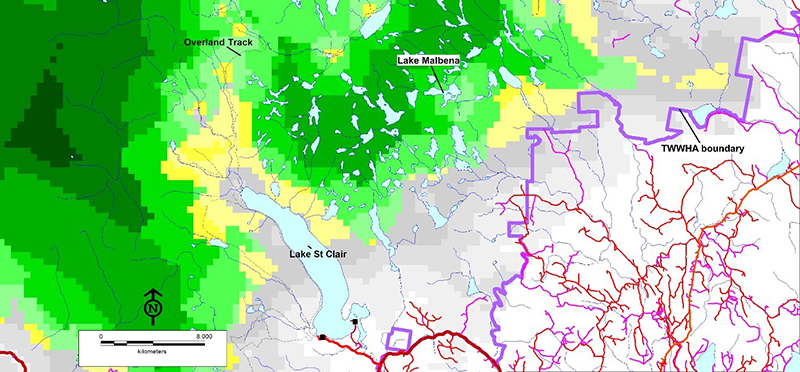

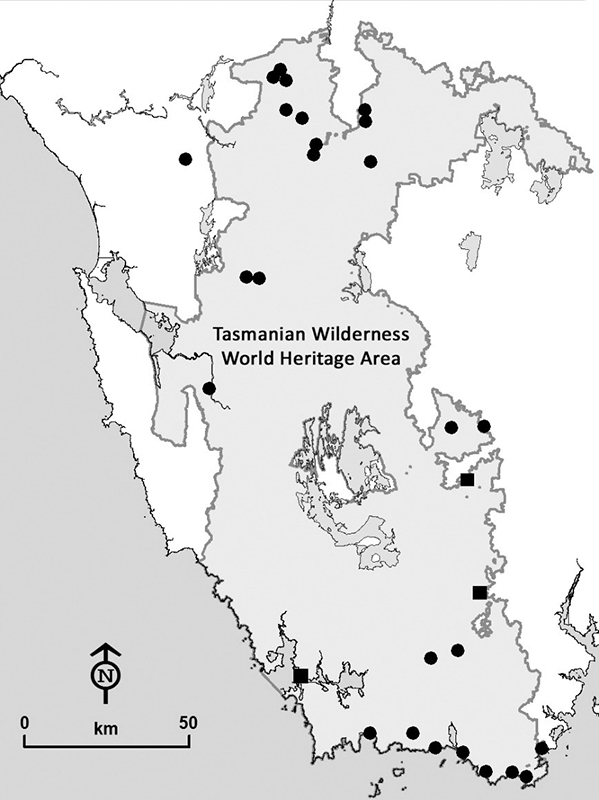

Figure 1 – Australian state of Tasmania showing the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area and the location of Lake Malbena.

A proposal for a helicopter-based luxury tourism development in a remote part of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA) attracted widespread public opposition, particularly from wilderness enthusiasts and recreational users of the area. The controversy highlighted a range of issues relating to wilderness protection and management, including concerns about the lack of transparency in the development-proposal assessment process; the impacts of such developments on the area’s primitive and remote character; the risk of ongoing, incremental loss of wilderness values; the commercialisation of public assets; and access equity issues.

Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA)

The TWWHA encompasses nearly 1.6 million hectares (almost 4 million acres) of mountainous, largely natural country in Tasmania (Figure 1) and includes extensive areas of temperate wilderness. The reservation and creation of the TWWHA has largely come as a result of more than four decades of environmental advocacy beginning in the 1970s, and “wilderness” has been at the heart of these campaigns.

The attribute of wilderness has been recognized as part of the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of the TWWHA since its inscription on the World Heritage List (Law and Bayley 2018). Its 1981 nomination described it as “one of the last remaining temperate wilderness areas in the world” (Australia 1981). The 1989 proposal for extension noted “it is this wilderness quality which underpins the success of the area in meeting all four criteria as a natural property and which is the foundation for the maintenance of the integrity of both the natural and cultural values which are displayed” (Australia 1989). Evaluations by the International Union of Conservation for Nature (IUCN) affirmed the importance of wilderness (IUCN 1982, 1989). The World Heritage Committee has implicitly recognized the importance of wilderness to the character of the property by approving its name – the “Tasmanian Wilderness” (Law and Bayley 2018). The 2016 TWWHA Management Plan (DPIPWE 2016) appears to concur, describing wilderness as “fundamental to the integrity of the TWWHA.”

Law and Bayley (2018) note the World Heritage Committee has expressed concern about how wilderness is to be maintained within the Tasmanian Wilderness property. In 2015, it called for “recognition of the wilderness character of the property as one of its key values and as being fundamental for its management” and asked Australia to establish “strict criteria for new tourism development within the property which would be in line with the primary goal of protecting the property’s OUV, including its wilderness character and cultural attributes” (UNESCO 2015).

Statutory Responsibilities

The TWWHA is composed of several national parks and other reserved lands. Most Australian “national parks” are established and managed under state (provincial) legislation. In Tasmania, this comprises the National Parks and Reserves Management Act (2002). Schedule 1 of this act lists the objectives for the management of national parks, including “to preserve the natural, primitive and remote character of wilderness areas.”

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act (1999) forms the basis of Australia’s national commitment to manage and protect World Heritage properties. It identifies World Heritage as a trigger for active involvement by the Australian government in the treatment of sites that would otherwise be managed exclusively by states such as Tasmania (Law and Bayley 2018). In addition, under the Tasmanian Land Use Planning and Approvals Act (1993), local government (councils) can have a role in approving particular development proposals in the context of their respective Planning Schemes.

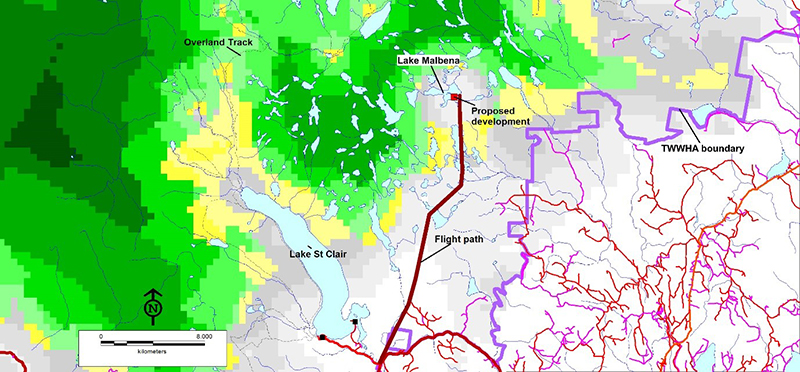

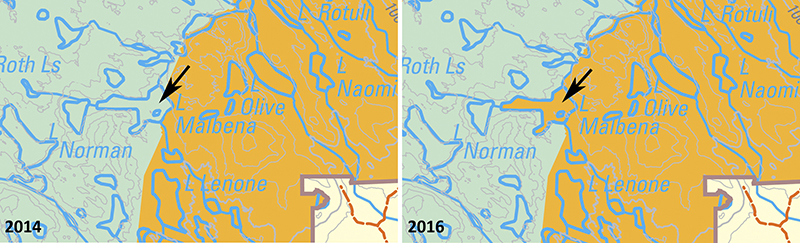

Figure 2 – Change in management zoning in vicinity of Lake Malbena, indicated by arrow; 1999–2016 (left) vs. final 2016 TWWHA Management Plan (right). Green = Wilderness zone, orange = Self-Reliant Recreation zone, yellow = private land outside the TWWHA. Halls Island is the prominent island in the southeast corner of Lake Malbena, (arrowed). Field of view is approximately 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) wide.

2016 TWWHA Management Plan

The TWWHA Management Plan is the primary guiding document for the region’s management, and, as a statutory plan, the Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service (PWS) is required to manage the areas concerned in accord with it. The Management Plan was formally reviewed from 2014 to 2016. The 2014 draft plan embodied a major political policy-driven downgrading of both the concept and management of wilderness. This attracted more than 7,000 critical public submissions, and “wilderness” was partly reinstated in the 2016 final plan.

Compared to its 1999 predecessor (PWS 1999), the provisions for the protection of wilderness in the 2016 Management Plan (Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment [DPIPWE] 2016) have clearly been weakened. The 2016 plan lacks a long-standing, overarching management objective to “maintain or enhance wilderness quality” (contained in the 1999 plan; PWS 1999). A Key Desired Outcome (KDO) that “wilderness is managed for the protection of the integrity and the natural and cultural values of the TWWHA and the quality of the recreational experience it provides” is articulated in the 2016 Management Plan (p. 175), but there are no stated actions or strategies to be employed to achieve the KDO.

In the 1999 Management Plan (PWS 1999), the Lake Malbena area was zoned “Wilderness,” which effectively ruled out any possibility of development. However, it was changed to “Self-Reliant Recreation” in the 2016 plan, not just in the Lake Malbena area (Figure 2) but also two other localities. This allows the consideration of “standing camps” but not huts (cabins) and facilitates development at the site. Of note is the timing of this change, after completion of public consultation and the final Director’s Report (which summarizes responses to said consultation). ENGOs (environmental nongovernmental organizations) believe the 2016 Management Plan was finalized with weakened protection provisions so that preexisting and subsequently proposed commercial tourism developments could be statutorily approved.

Nevertheless, some clauses remain in the 2016 plan that provide a basis on which to argue for wilderness protection. For example, the plan allows for certain activities to be undertaken, but this does not mean they are automatically permitted. They are still subject to other approval processes. Also, the management objectives of national parks and other reserves from the National Parks and Reserves Management Act (Schedule 1) are reproduced in the 2016 Management Plan and hence form part of the statutory plan, and section 1.5 of the plan makes it clear that Schedule 1 of the act applies to all areas of national park in the TWWHA. Hence, the objective “to preserve the natural, primitive and remote character of wilderness areas” not only applies under, but is unequivocally embodied in, the 2016 TWWHA Management Plan.

Tourism Master Plan

A Tourism Master Plan (TMP) for the TWWHA was requested by the ICOMOS/IUCN Reactive Monitoring Mission following its 2015 visit (Jaeger and Sand 2015). The World Heritage Committee concurred, identifying new commercial tourism development as a threat to the World Heritage values, including the wilderness character, of the TWWHA and calling for “the development of the Tourism Master Plan in order to ensure a strategic approach to tourism development … in line with the primary goal of protecting its Outstanding Universal Value” (UNESCO 2018, p. 135).

The process to develop a TMP finally commenced in 2019, and a draft was released in March 2020 (DPIPWE 2020). The TMP has arguably been preempted by the aforementioned changes to the 2016 Management Plan – changes that weaken protection and provide for the statutory approval of proposed private commercial tourism developments, such as the Lake Malbena development, and the government’s refusal to pause or review their Expressions of Interest (EOI) process while a TMP is prepared.

The EOI Process

Since 2014 the Tasmanian government has been inviting “Expressions of Interest (EOI) for Tourism Investment Opportunities” from private investors and tourism operators to “develop sensitive and appropriate tourism experiences and associated infrastructure” on reserved land across the state, with no clear requirement to comply with existing management plans. The documentation provided to proponents noted they were “not excluded from lodging an EOI Submission for a proposed development that is not fully compatible with the current statutory and regulatory framework, for consideration and assessment by the Minister” (DPIPWE 2014).

This process ran in parallel to the 2014–2016 process of reviewing the statutory TWWHA Management Plan. The assessment of EOIs was and is opaque, with a group making recommendations to the minister with no public scrutiny. Minister-sanctioned proposals were then forwarded to the PWS for further assessment and consideration for lease and licensing. But by this stage there is arguably a de facto expectation that projects will proceed.

Proposed Tourist Development at Lake Malbena

In response to the EOI invitation, a proposal was submitted in 2015 by Wild Drake Pty Ltd, a private commercial developer, for a helicopter-based luxury tourism development at Halls Island, in a remote part of the TWWHA. The proposal has drawn outrage from a wide range of people for a range of reasons, including the alienation of public land within a national park for the benefit of a private developer, but the most common theme is the impact of both the development itself and the associated helicopter access on the wilderness experience of existing users of the area (Tasmanian National Parks Association [TNPA] 2020).

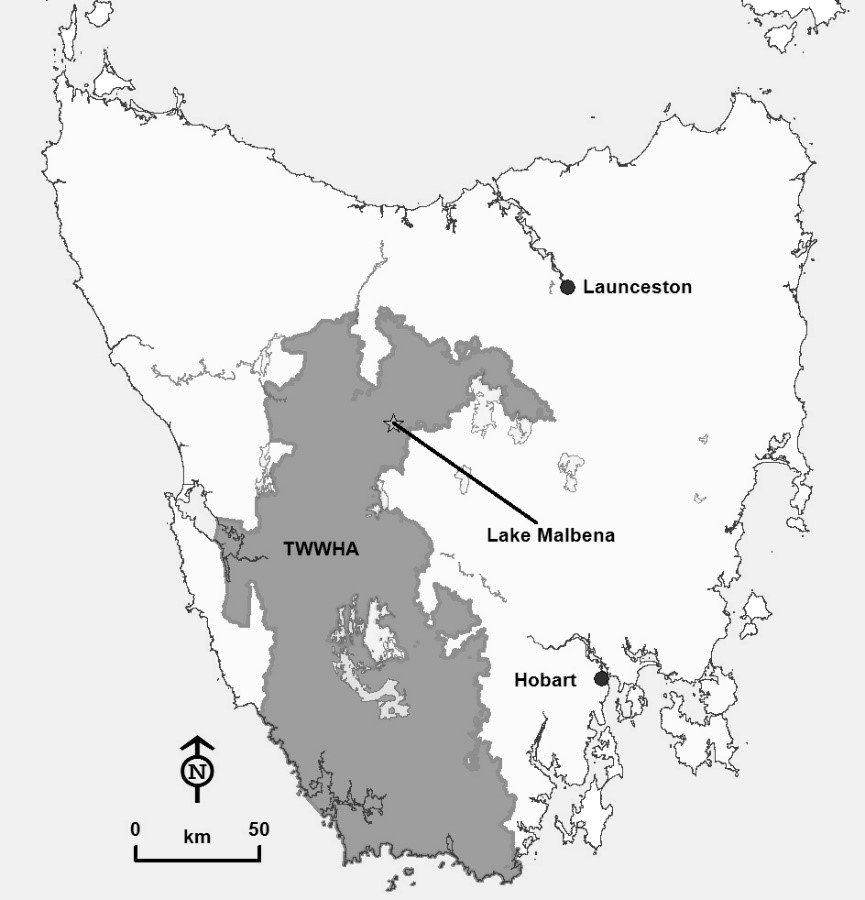

Figure 3a – Aerial view of Halls Island and Lake Malbena, surrounded by high-quality wilderness within the Walls of Jerusalem National Park. Photo: Rob Blakers.

Figure 3b – The existing small hut (cabin) on Halls Island, built in the 1950s. Nearby is the site for the proposed luxury helicopter-accessed development. Photo: Grant Dixon.

The mostly forested, 10-hectare (25-acre) Halls Island is in Lake Malbena, on Tasmania’s Central Plateau (Figure 3a). The area has high wilderness quality. It is remote; there are no formal walking tracks in the vicinity, and the easiest access route requires up to a day’s cross-country walking from the nearest rough road. It is also primitive and undeveloped except for a rudimentary small hut (cabin) on the island, built privately in the 1950s (Figure 3b). When this hut was constructed, the island was Unallocated Crown Land, but it has subsequently become part of the Walls of Jerusalem National Park and was incorporated into the TWWHA in 1989. The area and old hut have been enjoyed and freely used by bushwalkers (hikers) and fly-fishers for more than 70 years.

The proposed development would involve the construction of four buildings and four auxiliary structures, on a site of total area 800m2 (8,611 ft2). The accommodation buildings may be small but are arguably huts given their rigid structure, and there can be no doubt that the main communal building qualifies as a hut. The Management Plan (DPIPWE 2016, p.76) states that “standing (commercial) camps only” are permitted in the Self-Reliant Recreation zone (see Figure 2) and that huts are prohibited. Equally controversial, access to the proposed development would be by helicopter, with maintenance and client needs requiring several hundred flights annually.

In October 2018 it was revealed that the Tasmanian government had secretly granted the proponent an exclusive lease and associated business license over Halls Island, effectively privatizing part of the TWWHA (Denholm 2018). The main lease and business license were signed in January 2018, several months before any of the three main assessment and approval processes (see below) were finished. It might be justifiable to “enter lease and license negotiations” (the official line) before assessments are completed, but actually issuing a lease and business license prior to finalization makes a mockery of undertaking any assessment. Furthermore, a business license is the main vehicle for PWS to apply conditions to the operation of said business, so to issue it prior to finalization of the assessment of the business’s impacts is absurd.

The Approval Process

After the opaque EOI process assessment, the Lake Malbena proposal was invited by the minister to progress to lease and license negotiation with the Tasmania PWS in 2016. The development proposal required approval from all three tiers of government: state approval through the Parks and Wildlife Service’s Reserve Activity Assessment (RAA), a decision from the federal government about whether approval was required under the EPBC Act, and a final Development Application (DA) to local government, the Central Highlands Council (CHC).

The RAA process is the environmental impact assessment system the PWS uses to assess whether activities proposed on reserved land could have an impact on reserve values (DPIPWE 2016, p. 81). The PWS carried out this in-house assessment devoid of public input or external expert advice and, in March 2018, issued a “draft final determination” to approve the Lake Malbena proposal subject to conditions, pending the outcome of a referral for assessment under federal law (EPBC Act; see below).

The RAA was undertaken as a “level 3,” which does not provide for public comment. The RAA process is not defined in law (only a PWS policy document) so there are no appeal rights and no possibility of legal challenge. The document only became available after it was leaked in June 2018. The inadequacy of the RAA was then apparent; in particular, the remarkably superficial treatment of wilderness. Through a range of vague and demonstrably incorrect considerations, the RAA concluded there would be a “low level” impact on wilderness. Despite this, the RAA was then relied upon for subsequent approval under the federal EPBC Act.

The Lake Malbena proposal was referred to the federal Minister for Environment and Energy for a decision as to whether it required his approval under the EPBC Act. On August 31, 2018, a delegate of the minister decided the Lake Malbena project was not a “controlled action” and therefore it did not require detailed assessment or an approval under the EPBC Act (Department of Energy and Environment 2018). This decision was made despite a submission from a state government statutory advisory body, the National Parks and Wildlife Advisory Council (NPWAC), and more than 900 other public submissions, opposing the proposal. The Tasmanian Aboriginal Heritage Council and Australian Heritage Council also opposed approval.

NPWAC stated: “The proponent does not appear to address the fundamental concern that the proposal is for a development with several buildings, not a ‘standing camp.’” (The original intention of a “standing camp” was a temporary commercial bush camp, but the PWS “definition” has evolved over time to include structures that amount to huts (cabins) by any common sense definition. Indeed the proponent refers to them as “huts” at several places in the documentation of the proposal.)

NPWAC also stated: “[Re. helicopter access], NPWAC is concerned that without adequate consideration, precedents will be set that will degrade the World Heritage Values of the TWWHA…. NPWAC does not support this project progressing at this time and reiterates that contentious projects such as this should not be considered until there is an agreed framework to guide assessment.”

When the CHC advertised the DA for the Lake Malbena proposal, it received 1,346 submissions; only 3 supported the proposal. The CHC was required to determine if, under the Central Highlands Interim Planning Scheme 2015, the Lake Malbena development was “in accordance” with the TWWHA Management Plan. On February 26, 2019, the CHC decided to refuse the DA. A common theme of comments by the mayor and councillors was the inadequacy of the RAA and the failure of process; the state and federal governments had shirked their responsibilities (TNPA 2020). The proponent, Wild Drake Pty Ltd, appealed the CHC’s decision to refuse a permit to the Tasmanian Resource Management and Planning Appeals Tribunal (RMPAT).

Legal Challenges

The (Australian) Wilderness Society (TWS) sought a judicial review of the decision that the Lake Malbena development is “not a controlled action” under the federal EPBC Act. The merit of a decision cannot be challenged under judicial review; only the process by which a decision is made is open to review. TWS’s case questioned whether a legal error was made in concluding that no further assessment was required, and in not imposing any conditions to ensure significant impacts on wilderness values were avoided (TWS 2019).

The judgement (Federal Court of Australia 2019), handed down on November 12, 2019, did not provide for the total reassessment of the Halls Island proposal that was hoped for. It ordered the approval notice for development be set aside, to be reissued with enforceable conditions negotiated between the federal government and TWS. At the time of writing, this is pending. The judgment also contained strong criticism of the “de facto assessment process conducted by the [Tasmanian] Department [PWS], in negotiation with a proponent and out of public view.”

Two ENGOs, the TNPA and TWS (Tasmania), and two individuals made the expensive commitment of joining the RMPAT appeal to defend the CHC’s decision to refuse Wild Drake Pty Ltd a development permit. The case, involving many expert witnesses, was heard over seven days in June and August 2019. One of the major issues under consideration during the appeal was the proposal’s impact on wilderness; specifically, compliance with the relevant requirements of the 2016 TWWHA Management Plan (TNPA 2020).

The RMPAT released their disappointing final decision on December 18, 2019 (RMPAT 2019). The tribunal decided all that was required was for a Management Plan to exist and that an RAA had been completed by the PWS up to stage seven. This means that the tribunal did not believe it needed to assess compliance with the Management Plan, specifically the impacts on wilderness, and instead deferred to the RAA process entirely. This narrow view means wilderness impacts would not be considered by an independent body. French (2018) noted, “The decision was entirely legalistic, and in no way endorsed the specifics of the development.”

In January 2020, TWS, TNPA, and others filed an appeal to the Supreme Court of Tasmania against the RMPAT decision to grant a permit to Wild Drake Pty Ltd. They challenged the tribunal’s ruling that it could rely on the RAA to determine whether the Lake Malbena proposal is in accordance with the 2016 Management Plan, and that RMPAT should not have relied on the RAA decision because that decision was also defective. The court’s decision was handed down on July 13, 2020 (Supreme Court of Tasmania 2020), with neither of the grounds of appeal successful. This decision was disappointing not only for the future of Halls Island but also because it did not fully explain the court’s reasoning court and hence it is of limited use in clarifying the process for assessing future development proposals on reserved land. The court’s findings related only to this legal point, not the merits of the proposal itself.

The parties decided to challenge this decision and filed an appeal to the Full Court on July 27, 2020, arguing that the Supreme Court made several legal errors in reaching its decision. At the time of writing, the outcome of this appeal was still pending. If the appeal is upheld, it is hoped the Full Court will order that the RMPAT decision be set aside, and that the tribunal make a fresh decision in consideration of the extensive evidence relating to the merits of the proposal, including its adverse impacts on wilderness.

Figure 4 – Extant proposals for tourist accommodation and other development across the TWWHA. Black squares indicate proposals that were operational by early 2020.

Discussion

The Lake Malbena proposal is the first of many proposed new private commercial developments for the TWWHA (Figure 4) to reach the final stage of approvals, and the first test of a weakened statutory management plan, so-called criteria for assessment of new commercial tourism developments and the ability of federal environment law to protect World Heritage properties and values such as wilderness (TWS 2019). Given the supposed success of the Tasmanian government’s policy of “unlocking our national parks,” often quoted by other Australian state governments seeking to follow suit, the outcome may set a national precedent. Meanwhile, while the Lake Malbena issue has been playing out, since 2014, the number of commercial leases over reserved land issued by the Tasmanian government has more than doubled, and commercial licenses to operate on or use public land have increased even more dramatically (Baker 2020).

Impacts of the Lake Malbena Development

The nature and quality of the self-reliant recreational experience provided by the Lake Malbena area will clearly be negatively impacted by the loss of primitiveness associated with the proposed development. The extent of public opposition to the proposal and media rhetoric around it demonstrate that the developer has no “social license” to proceed. The effective privatization of an entire island within a World Heritage national park, especially as it was done prior to the finalization of any development approvals, clearly riles many. And the “equity of access” argument articulated by the developer hardly applies when one is talking about exclusive helicopter access to a luxury camp.

The luxury huts and associated buildings on Halls Island and a new point of commercial helicopter access will degrade wilderness values and impact on the experience of existing users of the region. It will substantially compromise the remoteness and isolation of the Lake Malbena area, its condition as a “largely unmodified natural setting,” and therefore the protection of the integrity and natural and cultural values of the TWWHA, and (as noted above) the opportunities that it provides for a challenging and self-reliant recreational experience.

The Lake Malbena area is mapped as high-value wilderness in the TWWHA Management Plan (DPIPWE 2016 p.176); despite this, the RAA for the proposed development only superficially addressed wilderness impacts. Hence, The Wilderness Society commissioned an independent desktop study of the impact on WC of the proposed Halls Island development (Hawes 2018) for campaigning purposes, using the same mapping technique utilized by the Tasmanian government’s previous wilderness assessments of the TWWHA (Hawes et al. 2015; DPIPWE 2016, p. 176).

Hawes (2018) demonstrates that the introduction of private, commercial helicopter access to Lake Malbena would degrade the WC of the surrounding areas. The fact that the development would be located outside the Wilderness zone would not prevent it from negatively impacting WC in the area. Losses would occur both inside and outside the Wilderness zone and the Walls of Jerusalem National Park. Indeed, the heaviest losses would occur inside the Wilderness zone (Figure 5). This loss is due to the reduction in access-time remoteness associated with allowing commercial helicopter access to the lake.

The established WC mapping technique is incapable of distinguishing the impact of the existing rudimentary hut (cabin) at Lake Malbena from that of the proposed new huts and associated infrastructure. But a more refined WC mapping technique (Hawes et al. 2018) would undoubtedly show the proposed new structures would have a significant additional negative impact.

Plans and Process

The 2016 TWWHA Management Plan (DPIPWE 2016) was finalized with “additional assessment criteria” for commercial tourism development. The criteria do not set thresholds or standards that new commercial tourism developments must meet. Instead, they simply dictate that a RAA must “consider” or “identify” certain things, offering no requirement that values will be protected. The Lake Malbena proposal is the first real test of these criteria and highlights their inadequacies.

The effectiveness of the plan’s wilderness protection provisions (or lack thereof) have also been found wanting. The 2016 plan lacks an up-front objective regarding wilderness management, although it does incorporate Schedule 1 of the National Parks and Reserves Management Act and so the objective “to preserve the natural, primitive and remote character of wilderness areas” is embodied in the Management Plan, albeit well-hidden.

The Management Plan (DPIWE 2016) contains entrenched confusion between the Wilderness zone, a management designation, and Wilderness Value (WV), the metric measuring wilderness quality or character (Hawes et al. 2015), and contains the implication that zoning is the main mechanism for protecting wilderness (Hawes et al. 2015, p. 177). Specifically, the plan asserts that Wilderness Value was used in the delineation of the Wilderness zone boundaries, despite poor spatial correlation between the Wilderness zone and areas of high Wilderness Value. Hence the plan obscures the reality that the impacts on Wilderness Value by development proposals can only be assessed by modeling them directly, and that Wilderness Value cannot necessarily be protected by management prescriptions based on zoning. Despite the fact that the infrastructure and access point associated with the proposed Lake Malbena development will be located outside the Wilderness zone boundary, Hawes’s (2108) analysis has demonstrated the development will have an adverse impact on Wilderness Value (or Wilderness Character, WC, as he terms it) and the uses that the Wilderness zone is intended to protect.

Effective assessment of impacts on primitive and wild character – for individual development proposals and to monitor incremental erosion of Wilderness Character over time – are crucial.

The Management Plan (DPIPWE 2016, p. 34) acknowledges the TWWHA is at risk of “cumulative impact over time,” and this is particularly relevant to its wilderness. Managers might reason that a particular development was acceptable because it only caused a small loss of WC, but a succession of such developments over time could cause a substantial loss of WC, and hence of the essential values for which the region was listed as World Heritage. Effective assessment of impacts on primitive and wild character – for individual development proposals and to monitor incremental erosion of Wilderness Character over time – are crucial. The plan contains no undertaking to model or monitor such incremental changes, let alone prevent them.

There is a clear lack of independence and transparency in the RAA process. PWS is an agency within a department of the Tasmanian government, and the RAA is nonstatutory, meaning it cannot be legally challenged by a third party. It does not guarantee community scrutiny or consultation, and in the case of the Lake Malbena RAA, the process was not opened for public input.

Under legislation currently being implemented, all development on public land in Tasmania will be assessed under a new Statewide Planning Scheme, and solely via the RAA process. At a minimum, developments on reserved land should be subject to a process that allows for public consultation on compliance with a Management Plan, and that this compliance must be able to be tested in an appeal to RMPAT.

The application of the EPBC Act and other legislative protections appears to depend on the attitude of the federal minister at the time. It is not a reliable means of protecting World Heritage properties in Australia and cannot be relied upon to ensure the protection of Outstanding Universal Values. The events concerning the proposed development at Lake Malbena have shown how inadequate the EPBC Act is when administered by a government that favors development over protection.

Law and Bayley (2018) list a range of bad precedents set by the events described herein:

- Governments abused due process by changing the Management Plan after the public-comment period in order to accommodate the proposed development.

- The Tasmanian government carried out a flawed assessment by deliberately excluding public input and expert opinion.

- No meaningful evaluation of the proposal’s impact on wilderness was undertaken.

- The federal government ignored advice from its own experts, as well as the overwhelming number of public submissions.

- The decision by the federal minister to approve the Lake Malbena development debased the EPBC Act.

- Both commonwealth and state governments actions have preempted the Tourism Master Plan long promised to the World Heritage Committee.

- Both governments have ignored commitments to protect wilderness.

Furthermore, the Tasmanian government issued a lease over public land and a license for a business to operate there prior to completion of any assessment of the impact of said business.

Law and Bayley (2018) further argue that, if ultimately approved, the moves by the governments prompt fears of additional impacts occurring through further stealthy incremental changes to the development. Such potential includes motorized watercraft on Lake Malbena, proliferating buildings, additional helicopter visits, new tracks, and motorized visits to lakes further afield.

Apart from the potential losses to wilderness, perhaps the biggest loss since 2015 is to the reputation of Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service. This agency, entrusted with the conservation management of the TWWHA and Tasmania’s other reserves, had a repu tation for professionalism and integrity throughout the decades of conservation campaigns leading to the creation of today’s TWWHA, but it has now come to be seen as merely facilitating commercial development.

Conclusion

This is not just the story of a lake in the Tasmanian Highlands, a tranquil spot largely free of evidence of modern technological society that has been enjoyed by generations of recreational visitors. It exemplifies a government policy attitude whereby everything (including nature) is seen as merely an economic asset, a failure of process verging on the corrupt, and the sidelining or ignoring of traditional stakeholders’ values. It is unfortunately also merely the latest salvo in decades of battles over nature conservation and wilderness in Tasmania.

The Lake Malbena proposal and approval process has raised the ire of broad range of interest groups and stakeholders. This is clear from the number of opposing submissions to the various approval stages (where submissions have been permitted), as well as the financial support offered to ENGOs to fund the various legal challenges. Opponents include recreational users (both hikers and fly-fishers) as well as members of academia and the Aboriginal community. The campaign moniker, “Reclaim Malbena,” illus trates the core concern of many of these stakeholders. But the issue must also be seen in the context of broader and growing public concern related to questions of over-tourism, “scenery mining” and “place piracy,” and the commercialisation of public resources, as well as increasing public awareness of the need for environmental protection.

Acknowledgments

This preparation of this article was greatly assisted by discussions with and the unpublished writings of Martin Hawes, Nick Sawyer, Geoff Law, Vica Bayley, and Tom Allen.

Since the text of this article was finalized, there have been some further developments in the legal challenges described on page 110.

In response to the Federal Court judgment handed down in November 2019, the federal Environment Minister has “remade” an earlier decision and determined the proposed development at Lake Malbena to be a “controlled action”, requiring a more thorough assessment under national environmental legislation (the EPBC Act). This is still pending. But, in her detailed Statement of Reasons, released in November 2020, the Minister “found that the impact on the world heritage values of the TWWHA from the use of helicopters is likely to be significant.” It is also encouraging that she accepted that wilderness-impact assessments “provide a useful demonstration of the possible extent of the impacts on exceptional natural beauty associated with the relatively undisturbed nature of the property, and the scale of the undisturbed landscapes”. These findings have much wider implications than for the Malbena issue alone, and they give additional weight to the credibility and utility of the wilderness-assessment process.

About the Authors

GRANT DIXON is an independent Tasmanian-based wilderness researcher, earth scientist, and nature photographer. He has previously worked with the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service and several ENGOs. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Grant_Dixon/research.

References

Australia 1981. Nomination of Western Tasmania Wilderness National Parks by the Commonwealth of Australia for inclusion in the World Heritage List. UNESCO. http://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/181ter.pdf, accessed March 22, 2020.

Australia 1989. Nomination of the Tasmanian Wilderness by the Government of Australia for inclusion in the World Heritage List, September 1989. Department of the Arts, Sport, the Environment, Tourism and Territories, Canberra.

Baker, E. 2020. The tiny island at the heart of the battle for Tasmania’s wilderness. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-22/halls-island-at-heart-of-battle-for-tasmania-wilderness/11983556, accessed March 22, 2020.

Denholm, M. 2018. Heritage isle in Tasmania now sanctuary for the rich. The Australian, October 26, 2018. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/state-politics/heritage isle-in-tasmania-now-sanctuary-for-the-rich/news-story/bd335ffc8b966a1573a2d00fca18f404, accessed March 22, 2020.

Department of Energy and Environment. 2018. 2018/8177 WILD DRAKE PTY LTD/Tourism and Recreation/Halls Island/Tasmania/Halls Island Standing Camp, Lake Malbena, Tas. Department of Energy and Environment, Australian Government. http://epbcnotices.environment.gov.au/referralslist/, accessed March 23, 2020.

Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. 2014. Tourism investment opportunities in the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, national parks and reserves. Unpublished EOI Guidelines, Attachment 2, p. 24. Hobart: Tasmanian Government, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment.

———. 2016. Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Management Plan 2016. Hobart, Tasmania: Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment.

———. 2020. Tourism Master Plan for the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Management Plan draft for public comment. Hobart, Tasmania: Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. March 19, 2020.

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act. 1999. (Commonwealth). https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2014C00506, accessed March 21, 2020.

Federal Court of Australia. 2019. The Wilderness Society (Tasmania) Inc v Minister for the Environment[2019] FCA 1842. Judgment, November 12, 2019. https://www.judgments.fedcourt.gov.au/judgments/Judgments/fca/single/2019/2019fca1842, accessed March 21, 2020.

French, G. 2018. Talking point: Don’t let chopper flights blot angling and wilderness gem. The Mercury, December 2018. https://www.themercury.com.au/news/opinion/talkingpoint-dont-let-chopper-flights-blot-angling-and-wilderness-gem/news-story/37c0860f4e190f8e77f93a0aed9b3dc2, accessed March 23, 2020.

Hawes, M. 2018. Lake Malbena wilderness assessment – The impact of the proposed Halls Island development on the wilderness character of Lake Malbena and surrounding areas. Report for The Wilderness Society, Tasmania. Unpublished.

Hawes, M., G. Dixon, and C. Bell. 2018. Refining the Definition of Wilderness: Safeguarding the Experiential and Ecological Values of Remote Natural Land. Hobart, Australia: Bob Brown Foundation.

Hawes, M., R. Ling, and G. Dixon. 2015. Assessing wilderness values: The Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, Australia. International Journal of Wilderness 21(3): 35–41, 48.

IUCN. 1982. World Heritage Nomination, IUCN Technical Review, 181 Western Tasmania Wilderness

National Parks. UNESCO, Paris. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/181/documents/%23ABevaluation, accessed March 22, 2020.

———. 1989. World Heritage Nomination – IUCN Summary, 507: Tasmanian Wilderness (Australia), October 1989. UNESCO, Paris. accessed March 22, 2020.

Jaeger, T., and C. Sand. 2015. Reactive monitoring mission to the Tasmanian wilderness, Australia, November 23–29, 2015. Unpublished ICOMOS/IUCN mission report.

Kirkpatrick, J. 2019. Scenery mining and place piracy – Managing the side-effects of Tasmanian tourism. In Tourism in Tasmania, ed. Can Seng Ooi and Anne Hardy. (pp. 40–51). Hobart, Australia: Forty South Publishing.

Law, G., and V. Bayley. 2018. Government push for tourism development undermines a proud record. World Heritage Watch Report 2018 (pp. 43–46). Berlin.

Mendel, L. 2002. The consequences for wilderness conservation in the development of the national park system in Tasmania, Australia. Australian Geographical Studies 41(1): 71–83.

National Parks and Reserves Management Act 2002 (Tasmania). https://www.legislation.tas.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-2002-062, accessed March 21, 2020.

Parks and Wildlife Service. 1999. Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Management Plan 1999. Hobart, Tasmania: Parks and Wildlife Service.

Resource Management & Planning Appeal Tribunal. 2019. Wild Drake P/L v Central Highlands Council and others [2019] TASPMPAT 28. Resource Management & Planning Appeal Tribunal (Tasmania), decision December 18, 2019. http://www8.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/tas/TASRMPAT/2019/28.pdf, accessed March 21, 2020.

Supreme Court of Tasmania. 2020. The Wilderness Society (Tasmania) Inc v Wild Drake P/L [2020] TASSC 34. Judgment, July 6, 2020. http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/tas/TASSC/2020/34.html, accessed July 21, 2020.

Tasmanian National Parks Association. 2020. Lake Malbena tourism development proposal – Background and summary, July, 16 2020. Unpublished paper, Tasmanian National Parks Association. https://tnpa.org.au/lake-malbena-development-proposal-background-summary/, accessed July 21 2020.

The Australian Wilderness Society. 2019. Why Malbena matters! Helicopter-accessed luxury accommodation development. Unpublished paper. The Wilderness Society, Tasmania.

UNESCO 2015. Tasmanian Wilderness (Australia) (C/N 181quinquies) Decision: 39 COM 7B.35

UNESCO. http://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/6290, accessed March 22, 2020.

UNESCO 2018. Decisions adopted during the 42nd session of the World Heritage Committee (Manama, 2018). https://whc.unesco.org/archive/2018/whc18-42com-18-en.pdf, accessed July 21, 2020.

Wolf, I., D. Croft, and R. Green. 2019. Nature conservation and nature-based tourism – A paradox. Environments 6: 104. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3298/6/9/104/pdf, accessed March 21, 2020.

Read Next

What We Have and What We Need

As we reach the end of the 26th volume of the International Journal of Wilderness, it is worthwhile to reflect on this year that was 2020.

A Tribute to Michael Soulé

The following is a tribute to the life and contributions of Michael Soulé from several colleagues and friends.

The Preservation Paradox: How to Manage Cultural Resources in Wilderness? An Example from the National Park Service

At the same time that federal agencies must comply with protection measures of the Wilderness Act, federal cultural resource laws require agencies to take into account the effects of federal undertakings on cultural resources.