Historic road through Cumberland Wilderness, NPS Photo credit © Scott Teodorski.

The Preservation Paradox: How to Manage Cultural Resources in Wilderness? An Example from the National Park Service

Stewardship

December 2020 | Volume 26, Number 3

“The wilderness was ‘ruined,’ not just once but repeatedly, yet it has returned, because its seeds and the needed nutrients survived in the earth. This wilderness says the potential of earth and life is eternal, built into basic reality from the beginning. This wilderness becomes a symbol of renewal, the downs and the ups, the cycles of forever, the majesty of the universe, the dignity of life” (National Park Service 1979, p. 429).

The US Wilderness Act of 1964 calls upon federal agencies to preserve wilderness character. Subsequent to the passage of the act, the earliest established American wilderness areas were located in mountainous land west of the Mississippi River, lightly inhabited historically, if at all, by Euroamericans. As a result of this western focus, wilderness lands were considered pristine, and conservationists considered evidence of Euroamerican habitation (and American Indian, too, if vegetation was altered), unwelcome intrusions. Western-centric perceptions of wilderness have influenced interpretations of the Wilderness Act, wilderness management guidance, and wilderness research.

At the same time that federal agencies must comply with protection measures of the Wilderness Act, federal cultural resource laws and policies require agencies to take into account the effects of federal undertakings on cultural resources (through the National Environmental Policy Act and the National Historic Preservation Act) and to protect and preserve important cultural heritage. Remnants of Euroamerican habitation are more frequent in wilderness areas established later in the eastern half of the United States. Managers of eastern wilderness areas struggle to comply with the Wilderness Act and cultural resource federal laws and regulations using wilderness management tools that are not designed to address cultural resource management.

Mandates to preserve both wilderness character and cultural resources set up a dynamic tension that I have termed “the preservation paradox.” How should the federal agencies that manage wilderness areas comply with both the Wilderness Act and cultural resource laws that call for consideration and appropriate management of cultural resources?

It is my purpose in this article to comment on court cases that examined management of cultural resources in wilderness and discuss an alternative reading of the law. Both sides of legal cases about management of wilderness cultural resources in the 11th Circuit and 9th Circuit Court of Appeals have made arguments that relied on incomplete understanding of cultural resource laws, legal inconsistencies, and previous cases that have influenced subsequent cases in nonproductive ways. A new reading of the Wilderness Act is needed to clear a path to consistent management of wilderness cultural resources.

Using the National Park Service as a case study, I identify ways that the recognition of cultural resources as a legitimate element of the fifth component of wilderness character as described in the Wilderness Act, and included in US federal agency wilderness character narratives, may influence future litigation. In view of a changing legal attitude toward wilderness cultural resources, I point to a need to update guidance for developing a wilderness character narrative and the execution of a minimum requirements analysis – two important management tools in the US context.

The National Park Service and Wilderness Management

The National Park Service (NPS) is the fourth largest US federal land-managing agency, having responsibility for 84 million acres (33,993,594 ha) of land. More than 40% of the lands that the NPS manages are designated or proposed wilderness. Unlike other federal agencies that manage land both for recreation and for resource extraction, the NPS has a single mission “which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations” (54 U.S.C. 100101). “Historic objects” we today call our cultural resources – historic and archeological sites, traditional cultural places, cultural landscapes, historic districts, buildings and structures, and museum collections.

A wilderness character narrative is one component of the US federal interagency strategy to improve stewardship by defining and monitoring qualities of individual wilderness areas over time. First proposed in 2008 (Landres et al. 2008), the strategy identified four wilderness qualities located in the definition of wilderness in the Wilderness Act (16 U.S.C. 1131-1136). Keeping It Wild: An Interagency Strategy to Monitor Trends in Wilderness Character across the National Wilderness Preservation System (Landres et al. 2008) listed “Natural,” “Undeveloped,” “Opportunities for Solitude and Primitive and Unconfined Recreation,” and “Untrammeled” as qualities comprising wilderness character.

The National Park Service added a fifth quality of wilderness called “Other Features of Value” in Keeping It Wild in the National Park Service (2014). This quality encompasses aspects of wilderness character that are of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value. It is based on the last clause of section 2(c) of the Wilderness Act, which states that a wilderness “may also contain ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value.” The fifth quality captures unique elements of the wilderness that may not be covered in the other four qualities. The updated interagency guidance (Landres et al. 2015) now lists “Other Features of Value” as a fifth quality of wilderness character to accommodate ecological, geological, paleontological, cultural, and other notable resources that make an area unique and worthy of wilderness status.

Because of a mission to preserve cultural resources, unique among federal agencies, the NPS has had a major role in developing policy toward management of cultural resources that are in wilderness areas. In the last decade, NPS cultural resource specialists have developed cultural resource technical guidance in wilderness management. Encouraged by the publication of Keeping It Wild in the National Park Service (National Park Service 2014), there have been several efforts to address a lack of technical guidance, including a special edition of Park Science and guidance produced by the NPS Archeology Program (https://www.nps.gov/archeology/npsGuide/wilderness/index.htm).

Federal Agencies versus Wilderness Litigation

Developing an appropriate balance between the dual responsibilities of caring for cultural resources and caring for wilderness has been an ongoing process, and decisions to preserve cultural resources in wilderness have been challenged in court. Six federal cases are directly relevant to our current perspectives on wilderness cultural resource management, of which three were filed against the National Park Service. The cases are:

- Wilderness Watch & Peer v. Mainella (Cumberland Island Wilderness, GA, 2004) (U.S. 11th Circ. 03-15346)

- Olympic Park Associates & Peer v. Mainella (Daniel J. Evans Wilderness (Olympic Wilderness), WA, 2005) (Western District, WA-C04-5732FDB)

- High Sierra Hikers Assn v. United States Forest Service (Emigrant Wilderness, CA, 2006) (CCVF05-0496AWI DLB)

- Wilderness Watch v. United States Forest Service (Kofa Wildlife Refuge, AZ, 2010) (U.S. 9th Cir. 08-17406)

- Wilderness Watch v. Y. Robert Iwamoto and the United States Forest Service (Mount Baker-Snoqualmie Wilderness, WA, 2012) (W.D.WA – 853 F. Supp 2d 1063)

- Wilderness Watch v. Creachbaum (Daniel J. Evans Wilderness (Olympic Wilderness), 2016) (W.D.WA.-C15-5771-RBL)

Wilderness Watch & Peer v. Mainella set a precedent for rejecting cultural resource contributions to wilderness character. While judges in the US Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit agreed that, in cases of ambiguity, deference should be awarded to federal agencies, they did not conclude that the Wilderness Act was ambiguous. They set thinking about wilderness cultural resources off-course by defining “historical use” to refer only to exploitation of natural resources in the historical past and, although the case did not consider management of cultural resources in wilderness areas, offered that:

“We cannot agree with the NPS that the preservation of historical structures furthers the goals of the Wilderness Act. The Park Service’s responsibilities for the historic preservation … derive, not from the Wilderness Act, but rather from the National Historic Preservation Act. (Wilderness Watch & Peer v. Mainella 2004)”

The 11th Circuit Court’s statement ignored the fact that Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act does not mandate historic preservation, but only that a process be followed for considering effects of federal undertakings on historic properties. Thus, through a misrepresentation of the National Historic Preservation Act, and alienation of the Wilderness Act from requirements to preserve cultural resources, the judges in Wilderness Watch & Peer v. Mainella stripped protection from historic properties located in wilderness. Furthermore, the judges did not consider the language of the NPS Organic Act quoted above when writing, “Absent … explicit statutory instructions, however, the need to preserve historical structures may not be inferred from the Wilderness Act nor grafted onto its general purpose.”

These pronouncements were seized upon in Olympic Park Associates & Peer v. Mainella. The judges in this case found the 11th Circuit Court’s arguments “persuasive.” The 9th Circuit Court’s ruling established a legal hierarchy in which the Wilderness Act, because it contained specific provisions, took precedence over the National Historic Preservation Act, which is a procedural law. It further disassociated cultural resources from any aspect of wilderness character, making it difficult for federal agencies to successfully argue that preservation of wilderness historic properties could further the goals of the Wilderness Act. Again, neither sides of the case looked to the NPS Organic Act for authority to manage cultural resources in wilderness.

It isn’t until High Sierra Hikers Assn v. USFS that we see any change in the courts’ thinking about wilderness cultural resources. In this case, the court found:

“The Wilderness Act … specifically acknowledges “historical use” as one of the values the Wilderness Act seeks to promote. Thus, while it remains ambiguous whether “historical use” can justify the maintenance, repair, or operation of structures that would otherwise be offending, at least it is clear that the purpose of the Wilderness Act is not directly offended by actions that seek to preserve historical use. Thus, at a minimum, the Wilderness [Act] is ambiguous with respect to the proposed preservation of dam structures on the grounds of historical use. (High Sierra Hikers Assn v. USFS. 2006. CCVF05-0496AWI DLB)”

In contrast to findings in Wilderness Watch & Peer v. Mainella, this case associated “historical use” with cultural resources.

In Wilderness Watch v. Y. Robert Iwamoto, the court affirmed that the presence of historic buildings does not categorically degrade wilderness character and deferred to agency judgment concerning appropriate treatment and commented:

The impact of merely allowing a pre-existing historical structure to remain in a wilderness area is quite different than the impact of taking affirmative action to preserve the structure, as the impact of minimal maintenance versus the aggressive reconstruction efforts…. The Court does not presume to know exactly where the line should be drawn. (Wilderness Watch v. Y. Robert Iwamoto and the United States Forest Service 2012)

The court in this case relied on the managing agency to distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate levels of intervention for preserving historic resources in wilderness.

Lawyers in Wilderness Watch v. United States Forest Service (2010) were able to successfully demonstrate that deference should be accorded US federal agencies in wilderness management of animal species because ambiguity existed in the law. This success was seized upon by lawyers in Wilderness Watch v. Creachbaum, arguing that a similar ambiguity existed with respect to cultural resources. Wilderness Watch alleged that the NPS had violated the Administrative Procedure Act by improperly interpreting the Wilderness Act and carrying out preservation activities on five historic structures in the Daniel J. Evans Wilderness (formerly known as Olympic Wilderness) between 2011 and 2015.

Figure 1 – Botten-Wilder Patrol Cabin is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Henry Botten built this hunting cabin in the present-day Daniel J. Evans Wilderness in 1929. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

The court concluded that the Wilderness Act was ambiguous and deferred to the NPS’ interpretation that historic preservation work could further the goals of the act. Important in the decision, as well, was the acknowledgment of the fifth quality of wilderness character that included cultural resources among “Other Features of Value.” This enabled the NPS to successfully argue that historic preservation work could further the goals of the Wilderness Act.

The use of the Minimum Requirements Analysis process was also another important element in the successful defense. The minimum requirements analysis documented NPS considerations and allowed lawyers to demonstrate that proactive management of historic structures could be appropriate, and that the way the management was carried out could be consistent with the Wilderness Act. Solicitors successfully argued that cultural resource preservation was established wilderness management practice.

Evolution of a Legal Basis for Management of Wilderness Cultural Resources

Each of the court cases discussed above, along with federal policy developments concerning the fifth quality of wilderness character, have contributed important elements to a more nuanced interpretation of the Wilderness Act. Courts have moved from asserting that actions to preserve cultural resources in wilderness conflict with the Wilderness Act to deferring to agency judgment that cultural resources can further the goals of the Wilderness Act. This resolution has relied, however, on the identification of discrepancies in the law, which can be, and have been, variously interpreted and are subject to change and new interpretations.

In the earliest cases, Department of Justice solicitors argued that the National Historic Preservation Act provided the authority to preserve historic buildings. As both the US 11th and 9th Circuit Courts demonstrated, the act does not dictate outcomes, and the federal agencies lost both cases. Lawyers for Wilderness Watch pointed out that because the Wilderness Act does mandate outcomes it takes precedence. In addition, the National Historic Preservation Act only concerns itself with properties that are eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. There may be additional properties worthy of preservation, because they are important to descendent communities, for example, that do not meet National Register criteria.

What the federal solicitors might have done, however, is argue that the NPS Organic Act provides further authority for historic building preservation activities. Chellis (2017), in an analysis of Wilderness Watch vs. Creachbaum, argues that Department of Justice solicitors should have looked to the legislation establishing the Daniel J. Evans Wilderness and, specifically, to the legislative history to demonstrate that the Washington Park Wilderness Act of 1988 was intended to include preservation of historic backcountry cabins and shelters. While useful in demonstrating preservation protection for a specific case, this does not provide blanket discretion for cultural resource action in every NPS-administered wilderness.

The Wilderness Act stipulates that the provisions of the act are to be carried out in concert with other laws, “the designation of any area of any park, monument, or other unit of the national park system as a wilderness area pursuant to this Act shall in no manner lower the standards evolved for the use and preservation of such park, monument, or other unit of the national park system” (Wilderness Act, S)ection 4[a3] (italics added). Thus, actions that curtail the National Historic Preservation Act Section 106 process for considering activities to preserve wilderness historic buildings surely “lower the standards” evolved for the use and preservation of cultural resources. This is the crux of the preservation paradox for NPS wilderness managers.

The inclusion of a fifth quality of wilderness in the interagency wilderness management policy and individual agency policies, and implementation of technical guidance establishes an appropriate management of cultural resources as a standard wilderness management practice. Recognition of cultural resources as a component of the fifth quality of wilderness by the courts and, as such, within management purview, normalizes preservation activities related to historic buildings and structures. If successful, such a case would set precedent to allow federal agencies to exercise a wide range of management options to preserve historic buildings and structures in wilderness areas.

A New Interpretation of the Wilderness Act

A frequently overlooked section of the Wilderness Act supports the argument that the Wilderness Act was not meant to exclude cultural resource management. While the definition of wilderness is in Section 1(c) of the Wilderness Act (Pub. L. 88-577; 16 U.S.C. 1131–1136), there is additional comment in Section 4(c) about structures and installations:

(c) Except as specifically provided for in this Act, and subject to existing private rights, there shall be no commercial enterprise and no permanent road within any wilderness area designated by this Act and except as necessary to meet minimum requirements for the administration of the area for the purpose of this Act (including measures required in emergencies involving the health and safety of persons within the area), there shall be no temporary road, no use of motor vehicles, motorized equipment or motorboats, no landing of aircraft, no other form of mechanical transport, and no structure or installation within any such area.

Since the rest of this list consists of prohibited activities to be performed in the future, it makes the most sense that Section 4(c) prohibited any future structures or installations, not past ones. Viewed in this way, historic buildings and structures that existed when the wilderness was established as a legal entity that are part of the “Other Features of Value” quality do not have a negative relationship with other qualities of wilderness character. Instead, the relationship between historic buildings and structures and other wilderness values is neutral. They are inert elements on the landscape, and their continued existence does not alter their relationship to the “Natural” and “Undeveloped” wilderness character qualities as described in the Wilderness Act and the Keeping It Wild strategy.

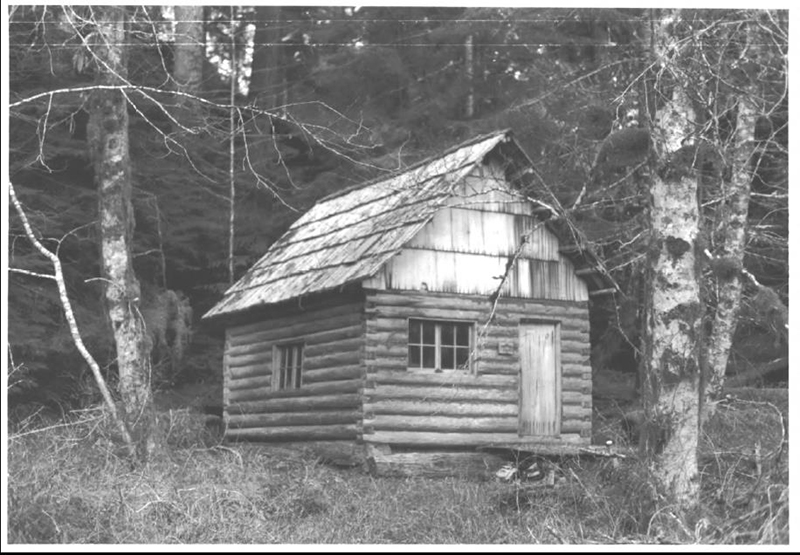

Figure 2 – Canyon Creek Shelter is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Civilian Conservation Corps built this log structure in the present-day Daniel J. Wilderness in 1939. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

The exception to this relationship is cultural landscapes. Cultural landscapes are frequently composed of living elements – orchards, fire-maintained glades, and abandoned fields, for example. Manipulation of plant and animal communities to maintain a cultural landscape has unavoidable and often unforeseeable effects on other species. A minimum requirements analysis to assess efforts to maintain or restore a cultural landscape may find that the “Natural” and “Undeveloped” wilderness qualities are significantly affected.

The Fifth Quality of Wilderness Character and Minimum Requirement Decision Guide

US federal management tools, including the wilderness character narrative and the minimum requirements analysis, require revision to better accommodate cultural resources. There have been inconsistent efforts to integrate “Other Features of Value” into overall wilderness character narratives, especially if the features of value are cultural resources. This perspective has also had an impact on the development of the Minimum Requirement Decision Guide and training in using the decision guide.

The goal of the Minimum Requirement Decision Guide (Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center 2000) was to “develop a consistent process for considering the minimum requirements of accomplishing projects and activities in wilderness” (Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center 2000, Acknowledgements). The earliest iteration was developed through the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center. The guide consisted of a flow chart/decision tree to narrow down the minimum required management action, and a series of questions to help identify the minimum tools to carry out the proposed action. While the guide does not specifically exclude wilderness cultural resource preservation activities, it is a product of a five-decades-old paradigm in which wilderness was pristine land untouched by human actions.

By 2016, the flow chart and open-ended questions had evolved into a series of metrics to quantify the effect of proposed actions to benefit one wilderness quality on other wilderness qualities and to use the quantified results to decide about actions to take. Cultural resources were acknowledged as an appropriate management issue, as a historic cabin is included among minimum requirements analysis examples on the Wilderness Connect website (https://www.wilderness.net/MRA, accessed July 23, 2018). The analysis, however, concludes that the cabin is to be documented and left to decay, because it degrades other wilderness values.

As the Wilderness Connect historic cabin example demonstrates, the current design of the process always yields a decision that the best solution for historic building projects is to document and allow to decay. Three alternatives were considered in the exercise. Two alternatives proposed restoration; the third proposed documentation and decay. The metrics rubric is structured such that any action taken to repair or maintain a historic building automatically has a negative effect on two or three other wilderness qualities. This is further illustrated in the text of the Step 2 Determination for the historic Cutler Cabin:

Alternative 1 would preserve the value of the historic structure through stabilization and continue education and interpretation about the value of the historic Cutler cabin which benefits the Other Features of Value quality and meets the requirements of law and NPS policy. But it does not improve the Undeveloped quality of wilderness character because the structure remains in wilderness and it causes negative impacts to the Undeveloped and Solitude and Primitive Recreation quality of wilderness character by including the use of a helicopter. (https://www.wilderness.net/MRA, accessed July 23, 2018)

Some of the negative impacts cited here are due to the work to be done, and some of the negative impacts are from the very existence of the structure itself. The stabilization of the building was not considered a positive effect for “Other Features of Value” but was considered a negative effect for all other wilderness qualities. The current coding rubric of the Guide will always yield the same conclusion for all wilderness historic structures, as the same elements are always involved – the existence of a building and the need for action to preserve it. In light of recent court cases, which agreed that preservation of cultural resources furthered the purpose of the Wilderness Act, the rubric needs to be updated to accommodate cultural resource projects in a more equitable and flexible manner.

Addressing Step 1 of the MRA

While the Minimum Requirements Analysis is a decision guide, it also memorializes the steps taken to arrive at a decision. The US Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit scrutinized the minimum requirements analysis for the five historic cabins very closely in Wilderness Watch v. Creachbaum (2016). Given this development, it is important to acknowledge that agency policy and practice allow the preservation of cultural resources in wilderness. The wilderness character narrative for the wilderness in which the cultural resource is located should include contributing cultural resources as part of “Other Features of Value”; Step 1 of the minimum requirements analysis should discuss why this particular resource type is an essential component of this wilderness quality, and how it contributes to wilderness character.

The importance of the cultural resource as part of an anthropogenic landscape that is being rewilded should not be discounted. In the long-term, natural processes will likely prevail. In the short-term, there is much to be gained by preserving structures that are important to a current generation of a descendent community. At present, there are no mechanisms in the minimum requirements analysis to accommodate legal requirements of cultural resource management, such as consultation. Prior to initiating the analysis, National Historic Preservation Act Section 106 consultation should be carried out and the results of the consultation, if relevant, incorporated into the Step 1 discussion.

Addressing Step 2 of the MRA

In Step 2, methods for achieving the specific preservation goal and the effect of those actions on other wilderness qualities should be the focus of the MRA. The rubric and rubric metrics should reflect a neutral relationship between other qualities and the “Other Features of Value” quality.

As discussed above, viewing the relationship between the historic building or structure and other qualities of wilderness character as neutral allows wilderness managers to focus on the best way to carry out the specific project proposed and the effects that those actions will have on wilderness qualities. Any references to the negative effects that the continued existence of the historic building or structure will have on other wilderness qualities should be eliminated from the alternatives proposed. This approach does not contravene the necessity to manage wilderness as a whole. Instead, it is acknowledging that the continued existence of the cultural resource does not change (much less degrade) the other wilderness qualities (although the actions to preserve or maintain the cultural resource may temporarily affect other qualities) and is not relevant to the analysis. Ways that the alternatives can address results of any Section 106 consultations with descendent communities, including American Indian communities, should be encouraged.

Conclusion

This article briefly examines judicial rulings, legal interpretations, and guidance pertaining to the management of wilderness cultural resources. Recent court cases that have ruled in favor of federal agencies’ actions to preserve wilderness historic buildings signal that a more encompassing attitude is needed about managing wilderness and wilderness resources. While the judges in Wilderness Watch v. Creachbaum ruled that the park had acted appropriately in protecting historic buildings, their ruling might have set a wider precedent for future cases had the Department of Justice made greater use of the NPS Organic Act and the specific legislation and accompanying House Report that established the Daniel J. Evans Wilderness, in their arguments.

This article also argues that a new interpretation of the Wilderness Act Section 4(c) is needed in order to exclude cultural resources already present in the wilderness at the time of establishment from the list of prohibited uses. The previous interpretation has had a significant detrimental impact on guidance for development of wilderness character narratives and on the structure of the minimum requirements analysis. Both documents developed for the Daniel J. Evans Wilderness were scrutinized in the Wilderness Watch v. Creachbaum case. The recognition and inclusion of cultural resources in the wilderness character narrative is an important step to appropriate consideration of management alternatives.

Restructuring the process to eliminate the tension between wilderness values and cultural resources as represented by historic structures and buildings allows managers to focus attention where it is critically needed, on the minimum tools needed to carry out the specific projects, and the effects that these actions will have on other wilderness qualities.

Finally, this article offers suggestions for restructuring the MRA and guidance to facilitate a more consistent consideration of wilderness cultural resources in order to accommodate cultural resource management in a more equitable manner. The conflict between cultural resources and other qualities of wilderness character inherent in the analysis is a product of a dated wilderness paradigm that originates in a western-centric view of wilderness. Restructuring the process to eliminate the tension between wilderness values and cultural resources as represented by historic structures and buildings allows managers to focus attention where it is critically needed, on the minimum tools needed to carry out the specific projects, and the effects that these actions will have on other wilderness qualities. A minimum requirements analysis process that more easily accommodates wilderness cultural resource projects, and incorporating those changes in guidance and training, will allow wilderness managers to consider a wider array of management and preservation options and promote the health of wilderness character.

A minimum requirements analysis process that more easily accommodates wilderness cultural resource projects, and incorporating those changes in guidance and training, will allow wilderness managers to consider a wider array of management and preservation options and promote the health of wilderness character.

Cultural resources can contribute to wilderness character in a positive way. The remnants of past habitation do not contradict the definition of wilderness, as “the imprint of man’s work” is “substantially unnoticeable” (and more unnoticeable as time passes) and demonstrates that the “improvements and human habitation” were, indeed, not permanent. Moreover, many historic buildings and structures will likely eventually vanish. To see natural processes reclaiming houses, fields, walls, and paths is a powerful statement about the enduring qualities of wilderness.

About the Authors

KAREN MUDAR holds a PhD in anthropology from the University of Michigan and works for the US National Park Service. She has been involved with the preservation of cultural resources in American wilderness areas for more than a decade; e-mail: Karen_Mudar@nps.gov.

References

Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center. 2000. Minimum Requirement Decision Guide. http://npshistory.com/publications/wilderness/mrdg-2000.pdf, accessed December 20, 2019.

Chellis, C. 2017. Playing nice in the sandbox: Making room for historic structures in Olympic National Park. Washington Journal of Environmental Law & Policy 7(1): 35–64.

High Sierra Hikers Assn v. United States Forest Service. 2006. CCVF05-0496AWI DLB.

Landres, P., C. Barnes, S. Boucher, T. Devine, P. Dratch, A. Lindhom, L. Merigliano, N. Roeper, and E. Simpson. 2015. Keeping It Wild 2. Fort Collins, CO: US Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-340.

Landres, P., C. Barnes, J. G. Dennis, T. Devine, P. Geissler, C. S. McCasland, L. Merigliano, J. Seastrand, and R. Swain. 2008. Keeping It Wild. Fort Collins, CO: US Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-212.

National Environmental Policy Act, Pub. L. 91–190, as amended 42 U.S.C. 4321 et seq.

National Historic Preservation Act, Pub. L. 89–665, as amended 54 U.S.C. 300101 et seq.

National Park Service. 1979. Shenandoah National Park administrative history 1924–1976. Unpublished manuscript. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/shen/admin.pdf, accessed October 4, 2017.

National Parks Service. 2014. Keeping It Wild in the National Park Service. WASO 909/121797.

Olympic Park Associates & Peer v. Mainella. 2005. Western District, WA-C04-5732FDB.

Wilderness Act. Pub. L. 88–577, codified as amended at 16 U.S.C. § 1131–1136.

Wilderness Connect. Minimum requirements analysis. https://www.wilderness.net/MRA, accessed July 23, 2018.

Wilderness Watch & Peer v. Mainella. 2004. U.S. 11th Circ. 03–15346.

Wilderness Watch v. Creachbaum. 2016. W.D.WA.-C15-5771-RBL.

Wilderness Watch v. Robert Iwamoto and the United States Forest Service. 2012. W.D.WA – 853 F. Supp. 2d 1063.

Wilderness Watch v. USFS. 2010. U.S. 9th Cir. 08–17406.

Read Next

What We Have and What We Need

As we reach the end of the 26th volume of the International Journal of Wilderness, it is worthwhile to reflect on this year that was 2020.

A Tribute to Michael Soulé

The following is a tribute to the life and contributions of Michael Soulé from several colleagues and friends.

Good News: Wilderness Is Not a Victim of Our Current Intense Political Partisanship

As for intense political partisanships, it is a fact of life in our politics and will always be. But it need not high-center progress for wilderness.