Smartphone Forest Photo credit: kbk8196 on pexels.

Wilderness Solitude in the 21st Century: A Release from Digital Connectivity

Science & Research

December 2021 | Volume 27, Number 3

PEER REVIEWED

ABSTRACT

Recent advances in mobile communication technology have led to decreased opportunities for alone time within daily life. Perhaps as a result, the solitude and independence offered in wilderness landscapes has become even more valuable. This study synthesizes past research and theory to create a quantitative model of wilderness solitude with a particular emphasis on release from digital connectivity. Study participants were visitors to Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex during the summer and fall of 2017. Exploratory factor analysis reveals four components of wilderness solitude: Societal Release, Introspection, Physical Separation, and De-tethering from Digital Connectivity.

Contemporary understandings of wilderness solitude need an update. As a body of knowledge, most field research concluded toward the end of the 20th century with the focus of indicators primarily relating to visual-social encounter norms and issues of visitor-use density. However, a handful of studies utilized humanistic measures that sought to investigate wilderness solitude in relation to a visitor’s motivation and capacity to positively cope with time spent alone. These studies view solitude as a personal experience, in addition to a response to the environmental conditions and perceived crowdedness of a given wilderness area. This suggests that the ability to experience solitude is not only dependent on the social conditions they encounter but is also influenced by an individual’s potential to temporarily detach from societal norms and focus their attention inward. This study sought to begin the process of integrating these research frameworks but also considers the rapid acceleration of digital connectivity that has influenced society since the bulk of solitude research was conducted.

We start by briefly reviewing past wilderness solitude research and then outline some of the more recent changes brought on by mobile technology. We then present and test an enlarged model of wilderness solitude that includes variables related to digital connectivity. It is our hope that researchers and managers might continue to consider a broad range of experiential conditions (both external and internal) that impact visitors seeking opportunities for solitude within units of the National Wilderness Preservation System.

Solitude as a Complex Research Topic

Wilderness solitude has long been an elusive concept. The Wilderness Act of 1964 is relatively terse when it calls for the provision of “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation.” Engebretson and Hall (2019) suggest that “there has been and continues to be a lack of clarity about the meaning of the whole phrase.” Nevertheless, wilderness researchers have pursued two frameworks of inquiry into the experience of wilderness solitude and identify a suite of possible indicators or desired conditions. Those frameworks of inquiry are: (1) the physical isolation perspective, which aims to measure threats to solitude with an emphasis on visitor use density, number of encounters, and degree of privacy (Hammitt and Madden 1989); and (2) the psychological detachment perspective, which investigates an individual’s solitude experience in terms of personal introspection, sense of self, and a freedom from societal norms and roles (Hollenhorst et al. 1994). Common threads between these two perspectives are the objectives of determining the characteristics that define an individual’s direct experience of solitude and of identifying indicators that serve as a proxy to the subjective experience of wilderness solitude. We believe it is important to note:

The task of studying solitary experience is intrinsically difficult, [and] in one sense self-contradictory. In order to obtain information on what takes place when people are alone, their privacy must somehow be broken, thus, to a degree, negating the object of study. (Larson 1990, 159)

Within the physical isolation framework, threats to wilderness solitude have been most closely aligned with the social-spatial conditions within a given wilderness area, utilizing indicators such as visual or social contact, personal autonomy, and physical remoteness (Lee 1977; Hall 2001). Due to the comparative ease of documenting the number of encounters a wilderness visitor experiences across a landscape (during a certain amount of time), the themes of crowding and visitor use density have traditionally guided the development of models in which “opportunities for solitude” have been measured (Long et al. 2007). The physical isolation perspective “assumes that solitude is a psychological response to social conditions experienced in the wilderness setting. If crowding is low or encounter norms are not exceeded, opportunities for solitude are presumably high” (Hollenhorst and Jones 2001, 56). Subsequently, the concept of wilderness privacy was developed to further articulate this line of inquiry and, as Hammitt and Madden (1989) found, one of the most important aspects of wilderness privacy “was being in a natural, remote environment that offers a sense of tranquility and peacefulness and that involves a freedom of choice in terms of both the information that users must process and the behavior demanded of them by others” (293).

In contrast, the psychological detachment framework shifted the focus away from wilderness conditions relating to isolation potential and, instead, concentrated on aspects of wilderness solitude that foster personal growth and development, specifically relating to self-examination and sense of self (Young and Crandall 1984). Hollenhorst and Jones (2001) developed the following definition for this framework:

Solitude is psychological detachment from society for the purpose of cultivating the inner world of the self. It is the act of emotionally isolating oneself for self-discovery, self-realization, meaning, wholeness, and heightened awareness of one’s deepest feelings, and impulses. It implies a morality that values the self, at least on occasion, as above the common good (emphasis added, 56).

Instead of building an operational definition of solitude based around the social and environmental conditions of a wilderness landscape, the psychological detachment perspective suggests that solitude ought to be investigated through the internal conditions that an individual brings with them to the wilderness. In contrast to indicators of physical isolation, and the continued monitoring of trail encounters being the standard by which wilderness solitude is understood, Hollenhorst and Jones (2001) proposed that “there are other important factors related to social disengagement and opportunities for contemplative reflection that demand more managerial and research attention” (60). This suggests that freedom from societal norms and expectations are important conditions within the experience of wilderness solitude.

A New Epoch in the Human Condition

Major technological advancements since the turn of the century have added new considerations for the study of wilderness solitude. The advent of smartphones has dramatically changed the patterns and frequencies of social interaction within contemporary life – creating a higher quantity of relationships to manage (both personal and professional). Which makes it difficult for many individuals to experience moments of uninterrupted alone time. For this reason, face-to-face communication has quickly become a secondary option due to the overwhelming preference, and ease, of digital exchange. Although the ability to remotely communicate and share information with friends, family, and colleagues serves as an incredible tool – culturally, there has been less dialogue toward determining the appropriate use of our novel communication technologies. As a result of these sociodigital transformations, “Rapidly evolving information and communication technologies are seen as marking a whole new epoch in the human condition” (Wajcman 2014, 2).

As we plug in to our social circles via digital means, we expose ourselves to the norms and attitudes of various groups at all hours of the day. Perpetual access to social networking has amplified the voice and image of a physically distant public, producing an unrelenting sphere of social updates and political opinions that has the potential to drown out opportunities for internal dialogue and personal reflection (Deresiewicz 2009). Instead of increasing the quality of interpersonal relationships, mobile communication technology has increased the quantity of such relationships, which has stretched the individual thin and produced a demand for one’s attention that has left many individuals with overwhelming feelings of anxiety and stress (Alter 2017). The transition of social interactions from face to face toward screen to screen has produced a reliance on technological devices that our culture has never experienced before. Unfortunately, this newfound reliance has also evolved into behavioral addictions: to the physical medium of our mobile devices, as well as to the social networks harbored within them (Gao et al. 2018).

“…face-to-face communication has quickly become a secondary option due to the overwhelming preference, and ease, of digital exchange. Although the ability to remotely communicate and share information with friends, family, and colleagues serves as an incredible tool – culturally, there has been less dialogue toward determining the appropriate use of our novel communication technologies.”

Research conducted by the MIT Initiative on Technology and Self has found that younger generations of Americans are becoming more comfortable with certain technologies than they are with one another, with Turkle (2012, 295) concluding that if “the simplification and reduction of relationship[s] is no longer something we complain about… It may become what we expect, [and] even desire.” As we relinquish our private time to stay better connected with others, our personalities, and the stories behind them, now exist in both a physical and digital realm. This dualism has led to the development of a tethered-self: one that is always connected and always online (Turkle 2008). The notion of the tethered-self is one of electronic copresence: the individual is physically present in a fixed location while also able to manage social relationships that exist within online platforms. Cyberspace offers the opportunity for a second life, one where an individual can craft an idealized version of themselves – where idiosyncrasies can be filtered and a more polished version of one’s identity can be put on display. Because of this, individuals become tethered to the task of grooming their online identity, while also being drawn to these very devices that offer short-term amusement and gratification (Turkle 2008).

The emergent utility of device-based diversions is not without its limitations: “inevitably, the constant flow of communication requires negotiation over the allocation of time and attention in multiple temporal zones, causing communication congestion and conflicts” (Wajcman 2014, 159). And if such conflicts are not identified, or addressed, an individual can face obstructions within their understanding of themselves and their world. It is suggested that to best address these incidences of congestion and conflict, an individual benefits most from allocating their time and attention back to themselves in a more deliberate and personal manner (Buchholz 1997). Wilderness provides outstanding opportunities for such a reallocation of time and attention to take place.

When considering the continuing relevance of wilderness in contemporary society, one needs to look no further than the parallels between the accessibility and connectivity offered by automobiles and roadways in the early half of the 20th century, and the accessibility and connectivity offered by digital devices and high-speed communication networks in our current era. As Paul Sutter pointed out in his 2002 book, Driven Wild: How the Fight against Automobiles Launched the Modern Wilderness Movement, rampant road building and the proliferation of automobile manufacturing not only threated the integrity of wild landscapes to commercial exploitation and habitat fragmentation, but this era also changed the way in which people interacted with such landscapes. As more and more visitors remained on roadways and viewed the outside environment from the comfort of their vehicles, they limited their opportunities to immerse themselves in the experience of wild nature and cultivate a personalized sense of place. Similarly, our mobile technologies in the 21st century are designed to bring the luxuries and attitudes of modern life with us wherever we go and, therefore, have the ability to limit and isolate one’s connections to self, community, and the Earth. What makes wilderness environments significant in relation to the digital age is that these landscapes offer an opportunity to experience relief from the multifaceted stresses that such technologies can harbor within the placeless environment of cyberspace. Wilderness offers space and time for individuals to explore the subtle aspects of human life and community that are all too often omitted within the collectivism of digital culture.

This Study: Location, Sample Population, Methods, Results

This study used an on-site, quantitative survey to assess the level of importance wilderness visitors place on various experiential conditions relating to wilderness solitude. The goal of this study was to develop an operational model of wilderness solitude that incorporates the humanistic indicators of the psychological detachment perspective, with the more objective measures of the physical isolation perspective while also highlighting the conditions of contemporary digital culture that have emerged since those research frameworks were developed.

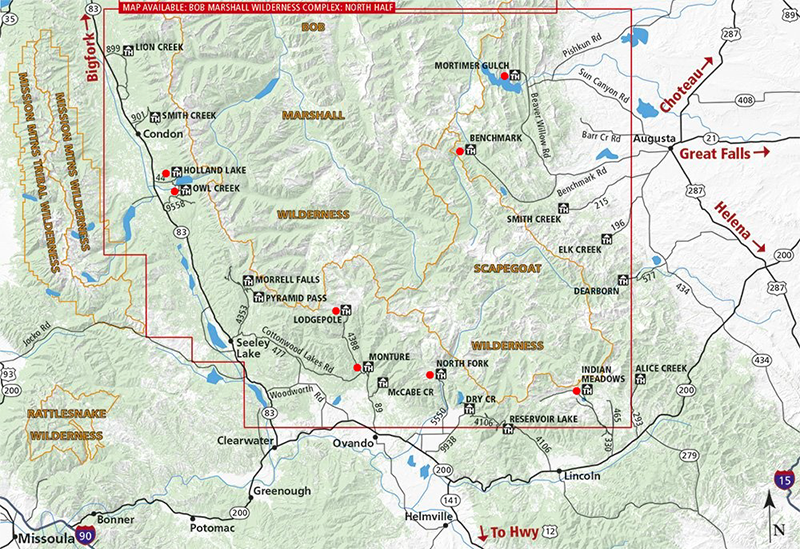

During the summer and fall of 2017, survey data was collected in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex (BMWC) in northwestern Montana. The BMWC comprises three contiguous wilderness areas: Bob Marshall, Great Bear, and the Scapegoat Wilderness, and covers over 1.5 million acres (607,028 ha) of rugged and remote designated wilderness. Field research was extended across three US Forest Service Ranger Districts within the southern half of the BMWC: Seeley Lake, Lincoln, and the Rocky Mountain Ranger District. Visitors were sampled at a total of nine trailheads, shown in red on Figure 1.

The population of interest for this study was wilderness users of the southern half of the BMWC. The sampling method used is considered convenience sampling, with a distinct limitation in its ability to accurately describe a specific population because some, rather than all, of the elements in the population are sampled (Vaske 2008). Therefore, the resulting data from this study is not a representative sample of wilderness users across the BMWC; however, a comparison with past social-science research in the BMWC conducted in 2004 by Whitmore et al. (2017) suggests little sampling bias exists. That is, while the analysis and results of this study do not make generalized claims about the sample population, the sample does allow for consideration of the content and reliability of a four-dimensional model of wilderness solitude.

Figure 1 – The high alpine ecosystem of the Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail

Most survey items assembled for this research were selected from statements that had been previously tested within the physical isolation and psychological detachment perspectives. Of the 22 items, two-thirds were taken from Driver’s (1983) Master List of Items for Recreational Experience Preference Scales and Domains and Hammitt’s 1982 study titled, “Cognitive Dimensions of Wilderness Solitude.” This helped ensure content validity with survey items that have already been shown to perform in a consistent and predictable manner and build on past findings within the wilderness solitude research tradition. New items focusing on digital connectivity and accessibility were derived from the themes and findings of recent scholarship on the affects and conditions of contemporary digital culture (Turkle 2008, 2012; Wajcman 2014). These new items have a particular emphasis on the importance of being away from the technologies and devices that demand attention and diminish private time. By synthesizing the two perspectives and incorporating ideas on digital connectivity and accessibility, an updated and comprehensive assessment of visitor preferences for conditions related to the experience of wilderness solitude has been achieved. The resulting scale, the 21st Century Solitude Scale, heeds the themes of self-reflection, isolation potential, and temporary avoidance of societal norms.

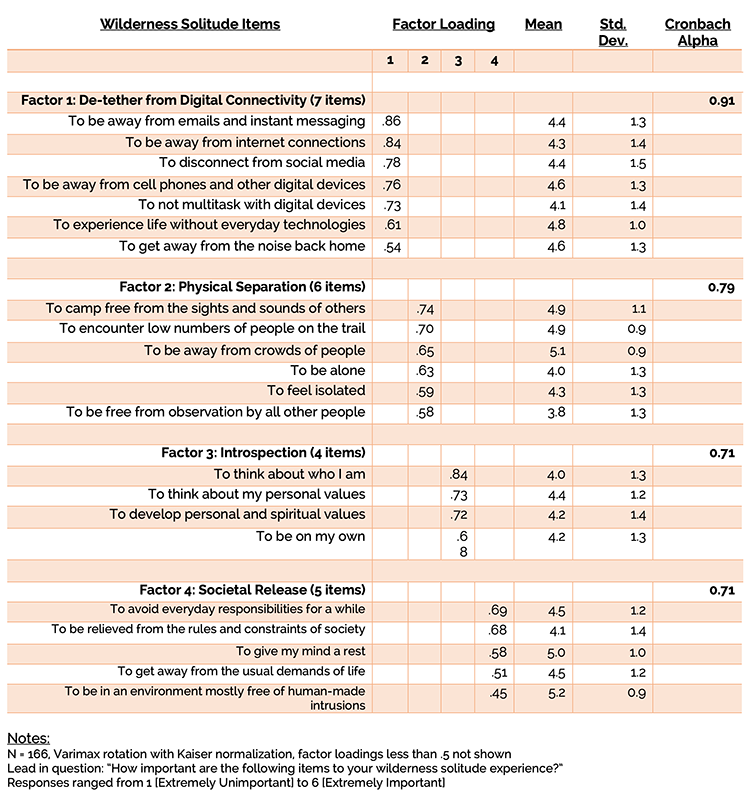

The survey was separated into three sections: (1) social demographics, (2) visitor motivations, and (3) preference for components of wilderness solitude. For the 22 questions on wilderness solitude, participants were asked, “How important are the following items to your wilderness solitude experience?” and they responded on a six-point (1–6) scale: Extremely Unimportant / Unimportant / Somewhat Unimportant / Somewhat Important / Important / Extremely Important.

A total of 32 sample days throughout late July to mid-October resulted in a sample of 166 respondents who were either entering or exiting the BMWC. The survey was conducted on-site and was both voluntary and anonymous. Due to extensive wildfire activity across western and central Montana during the 2017 season, visitation levels to the BMWC were lower than usual. However, the respondents were found to mirror the characteristics found in a comprehensive 2004 BMWC visitor study conducted by Whitmore et al. (2017): 77% were male, 78% had visited the BMWC previously (possibly indicating a continued increase in previous experience across the decades), about the same proportion traveled in groups of two to four people (67%), and the average age was very similar at 42 years old. The current sample had higher proportions of day visitors (42%), of anglers (46%), and of those who reported staying overnight in the wilderness, the average length of stay (2.8 nights) was slightly lower than reported in 2004 when it was 3.3 nights.

Analyzing the 21st Century Solitude Scale

One of the primary goals of this study was to determine the underlying structure of the wilderness solitude scale. For this reason, exploratory factor analysis, through the technique of principal components analysis (PCA), was performed on the dataset. PCA works to statistically identify communalities among certain scale items so that a large number of variables can be reduced and explained through grouped items: components (Kyle et al. 2020).

A Kaiser-Meyer Olkin (KMO) value of 0.856 suggests that the sample was a suitable candidate for PCA (Kyle et al. 2020). A Bartlett’s test of sphericity with an approximate Chi-square of 1931.417 with 231 degrees of freedom is significant beyond a 0.05 level, also signaling sufficient association to proceed with PCA. To determine the optimal number of components (or factors), the most used approach is the latent root criterion where only those components with eigenvalues greater than one are retained (Hair et al. 2018). This produced a four-factor solution that, combined, explained a satisfactory 60.9% of the variability within the 22-item wilderness solitude scale. A scree test criterion is used to confirm the selection of four components, where plotting the eigenvalues of each component shows a steep downward slope toward an inflexion point between the fourth and a fifth component. Beyond the fourth component, the scree plots flattens out (the “scree”) with each subsequent component contributing little additional explanation. Examination of an orthogonal rotation of the component matrix showed conceptual distinction between, and consistency within, four components. As a result, the analyses identifies four core dimensions within the 21st Century Solitude Scale, which we have interpreted as:

1. De-tethered from Digital Connectivity

2. Physical Separation

3. Introspection

4. Societal Release

Each of these four components have Cronbach’s alpha levels above 0.7, suggesting each grouping of questions is internally consistent and reliable (Kyle et al. 2020). The results of the factor analysis (component structure), as well as the mean and standard deviation for each of the 22 items, is shown in Table 1.

The first component (De-tethering from Digital Connectivity) explained 35% of the overall variation in response to the 22 items, indicating its foremost importance to the wilderness solitude experience. The remaining components (Physical Separation, Introspection, Societal Release) each explained a further 11%, 9% and 7% of overall variation. Factor loadings are high and all inter-item Pearson correlations within each factor were statistically significant above a .01 level. There were relatively few items (5) with cross-loadings across two factors (all of which were below a .50 cutoff, as appropriate for a sample size of 144 (Hair et al. 2018)). This suggests a conceptual distinctiveness and occasional intersection of the orthogonal components. For example, the item “To be alone” loaded strongly on Factor 2: Physical Separation (0.63) but also on Factor 3: Introspection (0.45). The item “To experience life without everyday technologies” loaded heavily on Factor 1: De-tether from Digital Connectivity (0.61) but also on Factor 4: Societal Release (0.45). We now turn to interpreting each of the four components.

Component Interpretations and Implications

De-tethered from Digital Connectivity

The De-tether component suggests that a lack of digital connectivity is an important experiential condition for wilderness visitors seeking solitude. The opportunity to exist without everyday technologies (particularly cell networks), to be away from emails, instant messaging, and social media is of great significance to both overnight and day visitors. By spending time away from the influences of digital culture, wilderness users have the chance to be more fully immersed in their immediate environment and less distracted by digital devices and the networks within them. Given the conditions of hyperconnectivity that encompass contemporary society, individuals who find it important to spend time away from internet and cell service value that wilderness areas allow a temporary release from the sensory overload and social pressures of modern digital life.

The implications for management within this component are complex. First, future pursuit of the installation of cell phone towers into wilderness, perhaps arguably justified based on visitor and administrative safety, could be counter to the definition of wilderness as areas of “undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvements or human habitation” (Wilderness Act of 1964). Wilderness is further defined to be in contrast to areas where humans and their works dominate the landscape, and we suggest the ubiquity of network service would render wilderness less distinct, and certainly less primitive. Further, as Howard Zahniser, the original architect of the act, reminded us in 1953, “We must remember always that the essential quality of the wilderness is its wildness” (1992, 52). Thus, what cell service would take from wilderness is not only an important part of the opportunity to experience wilderness solitude but also potentially its primeval character and influence – its wildness.

The importance of de-tethering has only just begun to be explored, and we encourage further examination in the context of wilderness experiences. The ideas of Sherry Turkle and Judy Wajcman provide one such foundation through their exploration of the shrinking of time and space in the face of modern technology and its impacts upon our sense of self and interpersonal relationships. The development of further indicators for the degree of de-tethering is suggested, as well as an investigation of their relationship to overall wilderness character. Lastly, a comprehensive research agenda focused on the relationship between digital connectivity and the use of mobile devices in wilderness areas is warranted (Dustin et al. 2019).

Physical Separation

The Physical Separation component of wilderness solitude suggests that avoiding crowds and having the opportunity to “camp free from the sights and sounds of others,” to “encounter low numbers of people on the trail” and to “be away from crowds” are significant experiential conditions for wilderness visitors seeking the experience of solitude. The items within Physical Separation also indicate the importance of feeling isolation and of being alone. Nevertheless, we note that the findings of this study demonstrate that Physical Separation is only one element within the phenomenon of wilderness solitude and that a relatively equal importance ought to be given to the other three components.

It is common practice to tally the numbers of encounters that visitors or wilderness rangers experience while in a wilderness area, or to count the number of occupied campsites in a particular location – as these are conditions that may threaten opportunities for wilderness solitude. However, these measures may not indicate opportunities for feelings of aloneness and isolation. Hall and Shelby (1996), for example, found that more than 50% of respondents contacted in the Eagle Cap wilderness either reported being unaffected by encounters or could not report a particular threshold beyond which encounters became detrimental to their wilderness experience. The question of how, when, with whom, and where encounters affect solitude deserves more attention, as does the development of indicators that are proxies for the experience of physical separation rather than threats to that experience.

Introspection

The Introspection component of wilderness solitude suggests that wilderness visitors who are seeking to experience solitude value opportunities to examine their personal values and a stronger sense of self. The establishment of this component helps expand the bank of potential indicators for monitoring wilderness solitude and supports past research as to its relevancy to the wilderness solitude experience. That is, a visitor’s internal conditions must be considered when determining if “opportunities for solitude” exist.

It is unclear what conditions most favor such opportunities for introspection (and was beyond the scope of this study), but we would expect that management decisions, particularly regarding rules and regulations, might directly impact these opportunities. Additionally, the implications of a lack of human intrusions (visual, olfactory, and auditory) upon the multisensory enjoyment of wilderness may be one theme that deserves further investigation. Again, potential indicators of introspection should serve as proxies for this experiential quality and be sensitive to potential threats to these opportunities. Part of the challenge presented by the Introspection component is the difficulty of measuring an individual’s subjective experience; therefore, qualitative research could be used to identify major themes and build a stronger understanding of the conditions relating to Introspection.

Societal Release

The Societal Release component suggests that wilderness visitors who are seeking to experience solitude find opportunities to spend time away from the usual demands of life to be important. To be relieved of the rules and constraints of society is also associated with this component, thus suggesting it is important wilderness continues to function as a contrast to mainstream society. Wilderness areas not only provide visitors with an opportunity to immerse themselves within a natural environment but also to have the chance to experience life without the norms, limitations, and social expectations of the built environment – one that is free of commercial influence and exploitation. That is, wilderness solitude is more than aloneness, it is a release from the expectations, demands, and pace of modern life. We think of this as somewhat akin to “stepping off stage” and taking a break from the gaze and influence of the physical or digital crowds. Engebretson and Hall (2019) similarly point out that within the crafting of the Wilderness Act, solitude was defined in contrast to the confusing sensory overload and pressure of modern civilization and mechanized culture.

Reminders of the built environment should be substantially unnoticeable such as the use of only very basic signs, limited manager presence, use of primitive tools and organic materials, and few restrictions on travel once inside wilderness. These conditions would not only provide the opportunity for Societal Release, but also signal deliberate restraint by managers. We believe these to be both important to the wilderness solitude sought by visitors but also to the untrammeled, primitive, and unconfined character of wilderness.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest wilderness solitude to be more than avoidance of other people. The four components of wilderness solitude indicate the importance of temporarily freeing oneself from the opinions, requests, and commercial interests that pervade daily life in the 21st century. In wilderness, there are opportunities for refuge, rest, and autonomy. Additionally, the sanctuary that can be discovered by visitors who turn their attention away from mass culture and reflect on the memories and experiences that define their lives is a major social benefit embedded within the original vision for wilderness. The chance to unplug is more important than ever, and this study supports the increasing relevance of wilderness solitude within the 21st century.

It is our belief that the measurement and monitoring of solitude should extend to the inward focus of the experience, which visitors reported to be important to their opportunity to experience solitude in wilderness. The emergence of the De-tethering component suggests that wilderness visitors are motivated toward unscripted and unmediated experiences that allow for self-discovery and reflective thought. Wilderness provides visitors with conditions that allow their personal time to remain personal, largely away from the algorithms, manipulations, and demands of modern, digital life. This study illustrates that solitude is a physical, psychological, and societal phenomenon, and for managers to protect this vital opportunity, the need to update our understanding of wilderness solitude grows more significant throughout each passing moment.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge the support and assistance provided by the W.A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation at the University of Montana, the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, and the Lolo National Forest.

About the Authors

THOMAS LANG is the founder of Stewardship Research & Consulting, LLC and lives in Helena, Montana; email: thomas.cavanaugh.lang@gmail.com.

WILLIAM T. BORRIE is with the School of Life and Environmental Sciences at Deakin University in Melbourne, Australia: email: b.borrie@deakin.edu.au.

References

Alter, A. 2017. Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked. London: Penguin Press.

Buchholz, E. S. 1997. The Call of Solitude: Alonetime in a World of Attachment. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Deresiewicz, W. 2009. The end of solitude. The Chronicle of Higher Education 55(21): 6.

Driver, B. L. 1983. Master list of items for recreation experience preference scales and domains. USDA Forest Service. Fort Collins, CO: Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

Dustin, D., K. Amerson, J. Rose, and A. Lepp. 2019. The cognitive costs of distracted hiking. International Journal of Wilderness 25(3): 12–21.

Engebretson, J. M., and T. E. Hall. 2019. The historical meaning of “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation” in the Wilderness Act of 1964. International Journal of Wilderness 25(2): 10–31.

Gao, T., J. Li, H. Zhang, J. Gao, Y. Kong, Y. Hu, and S. Mei. 2018. The influence of alexithymia on mobile phone addiction: The role of depression, anxiety, and stress. Journal of Affective Disorders 225: 761–766.

Hair, J. F., B. J. Babin, R. Anderson, and W. C. Black. 2018. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Hall, T. E. 2001. Hikers’ perspectives on solitude and wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 7(2):20–24.

Hall, T., and B. Shelby. 1996. Who cares about encounters? Differences between those with and without norms. Leisure Sciences 18(1): 7–22.

Hammitt, W. E., and M. A. Madden. 1989. Cognitive dimensions of wilderness privacy: A field test and further explanation. Leisure Sciences 11(4): 293–301.

Hollenhorst, S., E. Frank III, and A. Watson. 1994. The capacity to be alone: Wilderness solitude and growth of the self. International wilderness allocation, management, and research, 234–239.

Hollenhorst, S. J., and C. D. Jones. 2001. Wilderness solitude: Beyond the social-spatial perspective. Visitor Use Density and Wilderness Experience: Proceedings; 2000 June 13; Missoula, MT. Proc. RMRS-P-20. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Kyle, G., A. Landon, J. Vaske, and K. Wallen. 2020. Tools for assessing the psychometric adequacy of latent variables in conservation research. Conservation Biology 34(6): 1353–1363.

Larson, R. W. 1990. The solitary side of life: An examination of the time people spend alone from childhood to old age. Developmental Review 10(2): 155–183.

Lee, R. G. 1977. Alone with others: The paradox of privacy in wilderness. Leisure Sciences 1(1): 3–19.

Long, C., T. A. More, and J. R. Averill. 2007. The subjective experience of solitude. Proceedings of the 2006

Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium. GTR-NRS-P-14. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station.

Sutter, P. S. 2002. Driven Wild: How the Fight against Automobiles Launched the Modern Wilderness Movement. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Turkle, S. 2008. Always-On/Always-On-You: The Tethered Self. Handbook of MobileCommunication Studies: 121.

Turkle, S. 2012. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Ourselves. New York: Basic Books.

Vaske, J. J. 2008. Survey Research and Analysis: Applications in Parks, Recreation, and Human Dimensions. State College, PA: Venture Publications.

Wajcman, J. 2014. Pressed for Time: The Acceleration of Life in Digital Capitalism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Whitmore, J. G., W. T. Borrie, A. E. Watson, and K. Knotek. 2017. Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex (BMWC) 2004 visitor preference and usage data along with characteristics and attitudes towards fire management. Forest Service Research Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.2737/RDS-2017-0016.

Young, R. A., and R. Crandall. 1984. Wilderness use and self-actualization. Journal of LeisureResearch 16(2): 149.

Zahniser, H., and E. Zahniser. 1992. Where Wilderness Preservation Began: Adirondack Writings of Howard

Zahniser. Utica, NY: North Country Books Incorporated.

Read Next

December 2021

In this issue of IJW, we remember George Stankey and his contributions to wilderness research and stewardship. Mark Anderson provides a synthesis of recent findings on carbon storage in old growth forests. Rosemary Evans examines prescribed burning in Britain’s moorlands. And Tobias Nickel presents a call for a standard definition of “Natural” in wilderness stewardship.

Crises of Use

As we transition to a post-pandemic society, demand for transformational, restorative, and education experiences in nature will not recede. Nature has demonstrated its diverse benefits to a greater constituency these past months, and we as advocates, scientists, and managers need to embrace the challenge that comes with a larger audience.

George Stankey: Mentor, Colleague, Friend

George Stankey was a critical thinker who saw the big picture and could work across disciplinary boundaries.