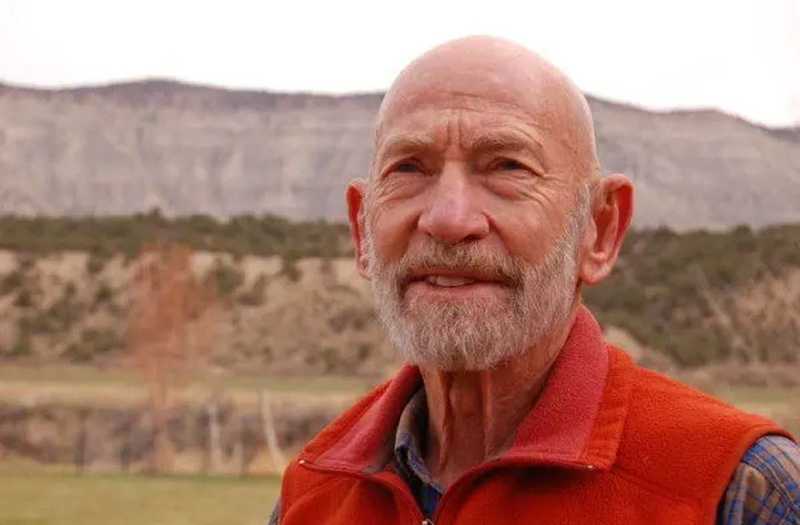

Michael Soulé and the Project Coyote membership

A Tribute to Michael Soulé

Soul of the Wilderness

December 2020 | Volume 26, Number 3

Michael Soulé passed away on June 17th, 2020 in Grand Junction, Colorado at the age of 84. He leaves a lasting legacy of conservation, paving the way and showing us all how to be better stewards of this planet. Photo credit © Rewilding Institute

Editor’s note: The following is a tribute to the life and contributions of Michael Soulé from several colleagues and friends. The Editorial Board of the International Journal of Wilderness would like to sincerely thank the authors for their contributions. We would also like to thank Project Coyote and The Rewilding Institute for granting permission to republish their tributes to Dr. Soulé.

In Memory of Michael Soulé:

Project Coyote Science Advisory Board, 2008–2020

It is with a heavy heart that we share that Project Coyote Science Advisory Board member Michael Soulé passed away on June 17 at the age of 84.

Considered the “father of conservation biology,” Michael cofounded the Society for Conservation Biology in 1985, also serving as its first president, and went on to cofound The Wildlands Project and serve as its president. He wrote and edited nine books on biology, conservation biology, and the social and policy context of conservation, and published more than 170 articles on population and evolutionary biology, fluctuating asymmetry, population genetics, island biogeography, environmental studies, biodiversity policy, nature conservation, and ethics.

I first met Michael in 2004 at a Society for Conservation Biology conference. A colleague introduced us, and I remember feeling a mixture of awe and excitement to meet this man I had long admired in the wildlife conservation sphere. I shared with Michael some of the work I was doing regarding carnivore conservation and predator management reform, and he encouraged me to publish and expose some of my findings.

Michael mentored countless conservationists – many of whom went on to have their own significant careers in wildlife conservation and environmental protection. Among his many noteworthy students was Kevin Crooks, whose seminal research with Michael in San Diego contributed to the mesopredator release theory. This ecological theory (developed by Michael to describe the interrelated population dynamics between apex predators and mesopredators within an ecosystem, such that a collapsing population of the former results in dramatically increased populations of the latter). Crooks, who was studying at the University of California at Santa Cruz, and Michael surveyed enclaves of land around San Diego. They found areas visited by coyotes had fewer small predators such as raccoons, skunks, and cats, but more native birds. Elsewhere, in areas devoid of coyotes, midsize predators like skunks and cats were common and birds were rarer. Describing the importance of this study and the theory behind it, Michael stated:

When we studied coyotes in the canyons of San Diego in the 1980s, we discovered that the canyons the coyotes still visited were healthier. There were more species of native birds than in those canyons that coyotes couldn’t access because they were isolated from the surrounding rural areas. That pattern has been seen around the world many times, where the large predators are removed and the populations of small predators, including raccoons, foxes and birds like ravens, jays, and robins explode. We call these smaller carnivores meso-sized predators. Their populations explode because there is no cap on predation or behavioral inhibition of their hunting. The smaller animals begin to go extinct in the area, as we saw in San Diego. When coyotes are present, housecats and other predators are much less active and don’t hunt as much. In this sense, it turns out that coyotes are good for native birds and ground nesting birds. These processes are called trophic cascades. You remove one part of the ecosystem, and it causes a ripple effect through other parts of the ecosystem that depended on the absent part. This can affect both flora and fauna. (Soulé 2020)

I was very fortunate that Dr. Soulé served on my graduate school thesis committee. It was during this time that I came to better understand Michael’s thinking around the need for protecting wildlife corridors and rewilding the continent with large carnivores – and for integrating compassion and consideration of animal welfare into the field of conservation.

After I completed my graduate studies in 2008, Michael became one of the founding Science Advisory Board members of Project Coyote (PC) when I founded the organization that same year. He joined a gathering of our Science Advisory Board in Yellowstone in 2014 where we discussed such issues as how we shift the paradigm of predator management in the United States toward carnivore conservation and stewardship and how we define coexistence with large carnivores (Figure 1). We broke out into small groups to discuss these issues, surrounded and buoyed by the beauty and magic of Yellowstone. In this short video, Michael is joined by fellow PC science advisors Dr. Paul Paquet and Dave Parsons in a discussion about how best to define coexistence.

To have been in the presence of these three giants in the field of carnivore conservation discussing what it really means to coexist with wildlife (when we were literally surrounded by wildlife!) is a cherished memory that will remain with me forever (Figure 2).

Before compassionate conservation became a movement and a field unto itself, Michael Soulé was advocating for the need to recognize and protect the interests and welfare of individual animals while also preserving biodiversity and species’ populations. A prescient visionary, Michael helped develop Project Coyote’s mission and vision, incorporating the concepts of coexistence and compassionate conservation into our work for wildlife and wildlands.

Those who knew Michael recognized that he struggled with grief and deep despair over the state of the world and our treatment of the planet and other sentient beings. He was a hyper-empath who felt the pain and suffering of others acutely – as well as the beauty and awe of wild nature. He shared that his Buddhist practice kept him mindful, aware, and centered in a world that he described to me as “unmoored” and “collapsing in despair.” I always wished I could have spent more time with Michael to absorb his knowledge, wisdom, and mentoring.

Going through old photos, videos, and e-mail exchanges with Michael since his passing has brought tears and laughter – and has served as a constant reminder of how fragile and precious this life is. One of my last exchanges with Michael included a sharing of Mary Oliver‘s poem, “The Summer Day,” where she asks: “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” Michael certainly had a plan with his one wild and precious life, and he executed it with gusto.

RIP Michael. You are missed by many and appreciated and loved by even more.

For you and the wild ones and wild spaces to whom you dedicated your life.

CAMILLA FOX is founder and executive director of Project Coyote; e-mail: cfox@projectcoyote.org.

Memories of Michael Soulé

I feel quite blessed to have been one of Michael’s friends. I’m not quite sure exactly how and when our friendship began, but I suspect it came about through my hanging out with Dave Foreman over the past 20 years or so and being invited on river trips. I know I was on the river trip where Michael met his wife, June, then known as Joli, whom I already knew through contra dancing. Many of you might not know that Michael was once an avid contra dancer himself. Michael was an immensely intellectual and humble man; he made friends with people from all walks of life. Yet he commanded the stage for decades as a world-class scientist in an equally humble manner. In my view, one of Michael’s most important contributions was the wedding of conservation science to conservation activism. This was his vision and the mission of the Society of Conservation Biology, which he founded. He believed that ecological science should serve a broader purpose than intellectual curiosity – it should serve the goal of saving nature from ravaging humans. Michael practiced what he preached. I have written many comment letters to the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) over the years, especially on issues of wolf recovery. I often asked scientists to endorse these comments, and Michael was always eager to sign on and add his world-renowned credibility to my recommendations, for which I will be forever grateful. Even in his final days on Earth, Michael was the first scientist to endorse comments submitted less than a week ago to guide the USFWS’s heretofore-misguided efforts to recover the critically endangered Mexican gray wolf. His name tops the list of over 100 scientists who endorsed those recommendations, which were submitted on behalf of Project Coyote and The Rewilding Institute. Thank you, Michael! Would you mind if I continue to add your signature to my future comments?

DAVID PARSONS is a Project Coyote science advisor and carnivore conservation biologist with The Rewilding Institute.

Memories of Michael Soulé

My last conversations with Michael were serenely revealing and left no doubt why Michaels’s legacy will be long-lasting and entirely admirable. He pondered on several occasions that among the few compensations of old age is the acuity of hindsight and how the awareness of limited time can paradoxically expand time. He spoke of being pleasantly overtaken by a feeling of the rightness and beauty and uniqueness of those he loved while in amazement of the curious ecstasy of simply feeling fine, feeling good.

He frequently reminded me that empathy naturally arises when the sense of oneness (nonseparation) is allowed to break through the ego’s defenses, having a constant and daily effect on our relationship with the world we live in. An ethical circle begins with a knowledge or feeling of relationship and the compassion that arises from that. Michael said all such “openings” offer a glimpse of the “truth” of nonseparation or the nondual. Although some people are deeply alarmed or frightened by the insights, others are joyous. Both can happen to the same person. He understood, however, that in an anthropocentric world, anyone who loves nature as much or more than they love people is going to be avoided or distrusted. Not surprisingly, he helped to get the field of conservation biology started, in large part, due to insight from such an experience.

Michael, you are thanked from the bottom of my heart for your always thoughtful counsel and all that you have so generously shared. In paraphrase of your own words, if nature had a voice (and any influence, besides “batting last”) I am sure that “she” would thank you too.

PAUL PAQUET is a Project Coyote science advisor and the Raincoast Conservation Foundation senior scientist.

The Conservation Movement’s True North

Conservationists and scientists around the world are mourning the death of Michael Soulé. Michael was 84. He was a dear friend, a great scientist, and a great warrior in the fight to save wild nature.

In Australia, Michael helped broaden and deepen our understanding of what “Nature needs to survive and thrive” on the Australian continent. His contribution to nature conservation in Australia is important now and will remain so far into the future. Our collaboration and friendship began in 2001 when, inspired by the US Wildlands project, The Wilderness Society (TWS) in Australia decided it needed a new strategic framework for its conservation efforts – a truly continental-scale approach, which would give nature the opportunity to continue its evolutionary path. As one of the founders of the Wildlands Project and a key advocate for its science-driven approach, Michael was a key player in continental conservation thinking globally. As then director of TWS, I pondered how we might involve Michael in the journey we had begun.

We were seeking an Australian adaption of the concepts pioneered by the US Wildlands Project in which Michael Soulé played such a seminal and visionary role. The 7th World Wilderness Congress in South Africa in 2001 to which we had both been invited provided the opportunity I had been looking for. My decision as director of The Wilderness Society in Australia to attend the World Wilderness Congress was driven by the opportunity to encourage Michael to help build and lead a group of high-level scientists to provide unfettered advice on “what nature needs” to strengthen the underpinnings of nature conservation efforts in Australia. We wanted to set up a team of the best environmental scientists in Australia to work with Michael and a continental-scale conservation program based on the best science available.

I managed to meet Michael and start talking to him about our ambitions, which we called the Wildcountry program, trying to persuade him to become involved. I think the main thing I persuaded him of was that I was totally passionate about protecting nature. This was a good start, but not enough. If Michael was going to work with us, we needed some heavyweight scientists involved. So, the fact that Brendan Mackey was also at the World Wilderness Congress in Port Elizabeth was indeed fortuitous. In the conversations that followed, Michael could see that the ecological processes that underpin the survival of nature in Australia needed to be elaborated and better understood by us all and that many of Australia’s top natural scientists were likely to be interested in contributing and could be encouraged to do so by his presence.

Once Michael committed to coming to Australia, he became a magnet that helped attract other scientists, and his involvement gave our continental-scale conservation ambitions a major boost. The Wildcountry Science Council was formed, cochaired by Michael and Henry Nix. The work done by the Science Council set a new level of ambition and scale for nature conservation in Australia.

Thus began a friendship that would last the rest of our lives. Between 2001 and 2010 Michael came to Australia at least once and often twice a year for extended periods. He would cochair the two-day Science Council meetings with Henry Nix, and then we would have a full work program for him ranging from meeting ministers and their advisors, meeting donors, spending time with grassroots groups discussing how to implement some of the connectivity principles on the ground, and meeting other experts and scientists involved in large-scale and particularly in connectivity conservation.

Michael had a particular interest in top-down regulation of ecosystems by predators, so in Australia Michael helped kick off an intensified discussion and new field research into the dingo and its role in suppressing cat and fox numbers. We also traveled extensively together in wild and remote places all over Australia. Michael was never happier than in a wilderness camp somewhere, discussing philosophy under the stars, with a glass of red wine or tequila. Even people who never met Michael will recognize his brilliant intellect through his many science papers, but I was fortunate enough to be able to hear his ideas firsthand and share his companionship and generosity of spirit.

I was fortunate enough to be able to attend Michaels 80th birthday in his hometown of Paonia, Colorado, with a great mix of friendly locals and various conservation luminaries. I spent a few days with June and Michael, either side of the party and I came away from the visit knowing that Michael was surrounded by people who loved and appreciated him and that he was content.

Many will speak of Michael’s uncompromising clarity of thought and advocacy for nature and the inspiration he gave people all over the world, but for me Michael Soulé was the “True North” of conservation. Michael’s vision for nature made it easy to navigate through a dark sea of mediocrity and false compromise. Michael’s intellect and clarity of purpose was like a giant compass needle that never failed to point us in the direction of what nature needed to survive. As a biologist Michael understood better than most both the inevitability and the necessity of death; he was at peace with its role in the universe.

The First Law of Thermodynamics states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed, and I like to think that the energy that manifested in Michael Soulé is now elsewhere in the universe, doing something interesting. Go well my friend, see you on the other side, don’t forget to chill the martini glasses!

ALEC MARR led The Wilderness Society in Australia from 1997–2010; e-mail: alec@strategicinterventions.net.

Soulé at the 7th World Wilderness Congress

Michael had an unshakable commitment to wilderness, and over many decades his was a seminal voice in reorienting nature conservation and defining a new, ecologically based human relationship with wild nature. In 2001 we had a global alert, a wake-up call that shook the world and especially the United States like nothing else before it. The terrorist contribution to globalization, 9/11 galvanized us in a way never previously imagined in the post–World War II era. On that day in early September, we were just seven weeks away from convening the 7th World Wilderness Congress (WWC) in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, with almost 1,000 delegates from some 50 nations committed to advancing the global agenda for wilderness protection from Africa, where humankind had evolved in wild nature and from whence the modern human species began its migrations some 300,000 years ago that eventually began to subdue wild nature around the world.

Our planning was thrown asunder as we faced a new, seemingly existential threat – should we postpone … cancel … or continue? We needed to act quickly. With colleague and friend Andrew Muir (Wilderness Foundation Africa and executive director, 7th WWC), we made the decision to continue, thereby becoming the first major global gathering to convene post 9/11. We lost hundreds of delegates who were unwilling or not allowed to travel, but we eventually convened 700 who were committed to the role of wilderness as a visionary answer of hope for a united and positive future. Michael Soulé was one of them, and he said to me when I asked him if we could count on him being at the Congress, “Of course we will be there. We need to counter the real terrorism, that which we are inflicting on wilderness.”

Figure 2 – Michael Soulé speaking at the 7th World Wilderness Congress in Port Elizabeth, South Africa.

And so, we gathered at this most unusual time, as stated in the opening lines of the Port Elizabeth Accord that framed the 7th WWC:

At this time in our history, when the shadow of uncertainty pervades our thoughts and the presence of peril dictates our actions, all our aspirations and initiatives must, by necessity, be positive, determined, visionary, and collaborative.

Michael was very on-target and uncompromising, of course. He called for an overhaul of the global conservation agenda in his plenary presentation, Wildlands Network Design. He posited that larger reserves and better connectivity constitute the foundation for any meaningful program of wilderness protection or nature conservation on a regional or continental scale, and the needed transformation is still possible in many parts of the world. The major elements of this new view of nature protection include (1) recognition of top-down regulation in ecosystems and the need for large core areas and regional wildlife linkages, (2) the need for ecological restoration on unprecedented scales, and (3) a critique of “fashionable alternatives” such as sustainable development.

His critique of sustainable development was as precise and charming as it was scathing, yet calmly delivered as was his style, ending in:

In fact, the ascendance of the notion of sustainable development has slowed efforts to increase the size and number of strictly protected areas worldwide, and sustainable development projects do more harm than good for nature and wildness.

In keeping with the 7th WWC’s call to action for positive solutions, Michael’s presentation ended with a summary of the value of the New Conservation Program presented in his plenary paper that he had developed in collaboration with the recognized and resolute conservation biologist John Terborgh:

A central concept of the new program for conservation is that large, interconnected, core protected areas are critical elements in regional wildland networks and, in these areas, the needs of large carnivores, other keystone species, and large-scale natural processes such as fire must be given priority over capital-intensive economic activity. Fortunately, it appears that nature protection benefits local communities materially and spiritually more, in the long run, than most economic development schemes that ultimately destroy environmental values and erode the communal bonds that bind people to the land and to each other.

Fast forward to 2020, and Michael passes from this planet in the year that the threat of pandemic is added to the list of escalating, existential environmental threats, joining climate breakdown and mass species extinction as a triad of systemic issues seriously obscuring humanity’s future. In the greater scheme of things and despite our own actions to the contrary, humans are not special and are, after all, just another species disregarding at its own peril the niche it occupies and polluting the promise it should not squander.

We can and must act on Michael’s words. His vision and “new conservation program” two decades ago are even more relevant and urgent today than they were then, because protecting intact wilderness and implementing large-scale ecological restoration is still the best, most rational, economically minded, and sustainable solution we have to the ever-increasing, radically present threats that we face today.

VANCE G. MARTIN is an associate editor of IJW, president of the WILD Foundation, and director of Wilderness Foundation Global; e-mail:. vance@wild.org.

Immortalizing Michael

The first time I met Michael Soulé, he was the dean of conservation biology. The second time, he was a frog.

That first meeting was the founding of North American Wilderness Recovery, which is now, almost 30 years later, Wildlands Network. Michael was a giant among giants at that inaugural meeting, and I (as the junior founding member, both intellectually and chronologically) listened in awe as he and Dave Foreman, Reed Noss, and other wilderness leaders explained to our host and sponsor, Doug Tompkins, how North American wildlife could be saved and restored. They outlined the “3 Cs” approach of designating large Core wild areas, reconnecting them via wildlife Corridors, and restoring keystone species, particularly the large Carnivores who keep ecosystems healthy – the basic approach of North American rewilding. Doug and his wife, Kris McDivitt Tompkins, then took the approach to South America; Michael and Reed soon explained it scientifically in their classic Wild Earth article, “Rewilding and Biodiversity: Complementary Goals for Continental Conservation”; and Dave soon expanded it into his landmark book Rewilding North America.

A year or so after that founding Wildlands meeting, our little Wild Earth editorial team drove cross-country in a talking station wagon that Kathleen Fitzgerald dubbed Norbert, to rendezvous in the Sonoran Desert with the Wildlands board and staff, our sibling group. Around the campfire one songful desert night – coyotes ululating, owls hooting nearby – the stories grew wilder and wilder. Wildlands Network always had more than its share of silverbacks, and this night several were in top form. Also, in attendance, though quieter, were some intellectually, spiritually, and physically attractive women, suspected of being potential or actual financial supporters; and psychologists could explain better than I whether their pulchritudinous presence might have influenced the showmanship of the campfire storytelling. In any case, my clearest memory from that distant campfire is everyone rolling in laughter as Michael, with his elven features, hopped around, imitating and telling us of some rare frog he’d found on a research trip years prior. I’ll never forget the twinkle in his eyes and the mischievously warm smile as he hopped past.

One more small reminiscence, of the many I’ll share with friends by campfires in coming months: Michael and I are driving together to a Wilderness Workshop event in White River National Forest, western Colorado. I’m quizzing Michael, who has begun a huge research and writing project on human nature and how we must understand it to address the extinction crisis. We agree that properly promoted, a book boldly titled SIN: 10,000 Years of Indolence, Sloth, and Debauchery might just sell, and might help scientists and activists build compassion for our wild neighbors. (With Michael’s family’s permission, we hope to soon share with Rewilding Earth readers some of the introduction from that unfinished work.) As Michael is explaining to me the biological basis for various human tendencies, I ask him to explain a few apparent anomalies. The one that he admits is hard to explain in evolutionary terms is this: Why do some people, me included, seem to have stronger nurturing instincts toward the young of other animals, particularly cats and dogs, than we have toward human children. (I admit to Michael, I never wanted kids, but I make an avuncular fool of myself cooing over kittens and puppies.) Maybe, Michael offered, we should simply celebrate that broader compassion as part of biophilia, part of humans’ affinity for other creatures, too.

Anyway, enough of my rambling. These stories I tell mainly to make the point that Michael should be celebrated and his legacy carried on not only for his brilliant scientific mind but also for his deep and broad compassion for others, his love for nature, his wonderful sense of humor, and his hard work to save the wild world.

Immortality is best achieved, I trust Michael would agree, through permanent protection of wildlands and their wild denizens. I propose we honor and immortalize Michael Soulé by finishing the Spine of the Continent Wildway – which he proposed as the flagship for a National Conservation Corridors campaign (see his article in Rewilding Earth entitled “A National Corridors Campaign for Restoring America the Beautiful”) – along the Rocky Mountains and restore the top predators, including gray wolf, grizzly bear, and puma, throughout. This we should be able to accomplish by 2030, in keeping with the popular Half Earth goal of protecting at least 30% of Earth’s lands and waters by 2030 and at least 50% by 2050. Two big steps this direction will be voting in Colorado this autumn to restore the wolf and electing a president and Congress who will begin protecting all public wildlands for their highest and best uses: as wildlife habitat, climate stabilizers, and quiet recreation grounds.

Like Frodo and Hayduke, Michael lives. The Spine of the Continent Wildway will embody Michael’s goodness forever.

JOHN DAVIS is the executive director of The Rewilding Institute; e-mail: hemlockrockconservation@gmail.com.

Michael Soulé’s Unpublished Thoughts on Sin and the Human Condition

Shared by Brian Miller

(BRIAN MILLER is a member of the Rewilding Leadership Council for Rewilding Earth.)

These thoughts are a brief summary of what Michael was thinking on sin and conservation. They also include some thoughts from private conversations we had over the recent years. His many, and influential, publications are well known. We want to keep alive these thoughts from his last writings – which he hoped would become a book that would help inform efforts to end the extinction crisis.

Scale is one of the most difficult concepts in ecology. Two people can be arguing a point, and sometimes both are right because they are thinking at different scales. Another misunderstanding comes when someone extrapolates the effect at one scale to a different scale. This can lead to false dualisms, and nearly all dualisms are false. Fire can keep you warm and cook your food. At a different scale fire can destroy large areas and take human lives. Good and bad can be situational.

So can sin. Historically, people have recognized “seven deadly sins,”, which are also called Horace’s Heptad. Horace laid them out in about the first century BC, and the Desert Fathers (early communities of Christian theorists) adopted them. Those sins are inclinations that can be good or bad, depending on the situation. At least five of those “sins” are firmly based in evolution. Greed, anger, lust, gluttony, and sloth were key parts of sexual selection going all the way back to the earliest forms of life. Those five are embedded in the shared DNA of all species. Pride and envy are more recent and perhaps cultural. We can add denial and despair to the cultural part of the Heptad.

In a nutshell, the five were key to survival and reproduction. Fitness in any species is defined by the contribution of genes you can leave in the next generation. For example, gluttony was adaptive because food sources for many species are scattered and irregular. The survival strategy is to consume as much as you can when you have the opportunity because the next meal may not present itself for a while. Some reptiles and amphibians can eat up to 70% of their body weight in one sitting. Physical sloth helped an individual recuperate energy expended by gathering food. Greed collected what one needed to survive. Anger spurred one into action, and together with greed, anger protected what one needed to survive. So, the five are adaptive in the natural world going back to the earliest forms of life. They help an individual to survive and reproduce. Reproducing increases fitness.

The key for humans and nature is that 10,000 years ago greed, lust, gluttony, sloth, and anger increased our individual fitness. The question now is: Can the planet survive the deadly sins at present human population levels, economic affluence, and technological level of sophistication? Planetary change is happening fast, perhaps 100 times as fast as just a century ago.

It took humans 200,000 years to reach a population of 1 billion. It took 200 more years to reach 7 billion. We are now at 7.8 billion, with predictions of reaching 10 billion by 2050. The rate of increase has been clearly exponential. Unfortunately, the rate of increase for resources humans use has been largely linear, and in relation to increasing the amount of area necessary to produce our needs. Right now, humans use over 70% of the ice-free land for food, fabric, building materials, and so forth. (Baillie et al. 2010). Slightly more than 40% of ice-free land goes directly to food production (Baillie et al. 2010; Crist et al. 2017). We use about 50% of the planetary fresh water, and about 80% of our water use is for agriculture (Crist et al. 2017). In some places, humans are withdrawing 4 to 6 feet a year from the Ogallala Aquifer, while nature is putting back half an inch (Little 2009). The aquifer is already dry in some parts of Texas and Kansas (Little 2009).

By 2050, we may reach 10 billion people, with a predicted per capita increase in buying power of 150% (Tilman 2012). The amount of land needed to feed us will double, and freshwater use will increase by 55% (Crist et al. 2017). Our food production causes 20% of the annual contribution of carbon to the atmosphere (Crist et al. 2017). The irony is that humans rely on a stable interglacial climate for food production, but our carbon contribution makes weather more and more erratic, potentially diminishing future food production.

Ninety-six percent of the global biomass of mammals is human and our domesticated animals (Yinon et al. 2018). The amount of agriculture to feed us has created 400 dead zones in the ocean (Crist et al. 2017). The rate of tropical deforestation is accelerating. Ocean life is already badly depleted. If we reach 10 billion in 2050, what will be left for other forms of life?

Added to growing human numbers is consumption. More people mean more consumption, but per capita consumption also increased by a factor of 40 from 1900 to 2006. The assumption of constant growth is false (Czech 2013). We cannot constantly grow with our limited resources. The Laws of Thermodynamics cannot be violated. Up to now we have been able to switch to a different resource when the one we had used expired. But we live on a globe, and if we keep gobbling up whatever is in front of us, eventually we come to our back door.

Right now, it takes about one year and seven months to replenish what humans use in a year (Crist et al. 2017). That is not a good strategy for long-term sustainability. All energy comes to Earth in the form of sunlight. We have been able to extend our growth by using past sunlight in the form of fossil fuels (Czech 2013). It takes millions of years to convert organic matter to oil fuels. They are not renewable.

So back to scale, I could swat at a mosquito that was biting me (only females draw blood – males eat nectar and pollen and thus pollinate). This is very different from trying to genetically alter mosquitos out of existence. Bats would be very unhappy if we did so. Another example is that jellyfish were clogging a nuclear power facility to the point that the facility had to temporarily close. The anthropocentric answer was to create robo-choppers that could chop jellyfish into pulp to the tune of 900 kilograms per hour (Crist 2014). That is different from swatting away a jellyfish while swimming. Sea turtles would not happy about the robo-choppers. The paradigm of constant growth is killing nature. We cannot continue to use 1.7 planets’ worth of resources. The only way we can grow our numbers and consumption is to take more from nature and other species. Eventually we will reach a ceiling, and the harmful effects of constant growth will fall on us. We are clever but not very smart.

What is an acceptable number of humans that can live well and still allow a significant portion of the planet to exist as nature? Many figures say around 2 to 4 billion (Crist et al. 2017). The key to reducing human numbers is empowering women, family planning, and readily available contraception. When women are educated, and have a place in society, birth rates and poverty are reduced. In Africa, a woman who didn’t go to school averages 5.4 children (Crist et al. 2017). With a high school diploma, the number of children per woman is 2.7. With a college degree the rate is 2.2. A replacement rate of 2.1 (or lower) with a longer generation time will lower population numbers over time. Available contraception will reduce unwanted pregnancies. Unfortunately, there is heavy political and religious opposition to empowering women. Some societies want to keep women barefoot and pregnant.

We conservation biologists are not optimistic, particularly in the short-term. Optimism and pessimism are rational responses to data analysis. But we have hope. Hope is irrational. You see a trend and try to change it. Hope has to be combined with passionate action.

We conservation biologists are not optimistic, particularly in the short-term. Optimism and pessimism are rational responses to data analysis. But we have hope. Hope is irrational. You see a trend and try to change it. Hope has to be combined with passionate action. Nelson Mandela thought he might be in prison for life, yet he never abandoned hope. If hope is combined with mental sloth it leads to inaction. Inaction implicitly supports the status quo.

For example, someone on Easter Island cut down the last tree, knowing that it was the last tree. They did it with the faith that their gods would take care of them. That is how we can add denial to Horace’s Heptad. Many have faith that we can persist no matter what (mental sloth) and deny that our actions can be harmful (climate change, extinction, COVID-19). Those imbued with feelings of human exceptionalism (anthropocentrism) put blind faith in technology. If fresh water is gone, then turn to desalinization. Global warming can be countered by shooting sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere. The list goes on. We must counter denial and delusion, and it will take a diverse group of people and skills. Students often ask, “What can I do?” Michael says, “Do what you do best.” Maybe you wanted to be a biologist, but you didn’t like organic chemistry or statistics. You can become a passionate lawyer defending nature against its enemies. Maybe you are an artist bringing a message for nature to the public. Maybe you study the political process and know how to get legislation passed. Maybe you are an activist and interlocutor for nature. Conservation is an interdisciplinary effort.

Michael was one of the best minds of this generation. He set the stage for the conservation movement of today. Never give up on the dream.

References

Baillie, J. E. M., J. Griffiths, S. T. Turvey, J. Loh, and B. Collen. 2010. Evolution Lost: Status and Trends of the World’s Vertebrates. London: Zoological Society of London.

Crist, E. 2014. Confronting Anthropocentrism. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZkFj9uPKXo&t=89s.

Crist, E., C. Mora, and R. Engleman. 2017. The interaction of human population, food production, and biodiversity protection, Science 356: 260–264.

Czech, B. 2013. Supply Shock: Economic Growth at the Crossroads and the Steady State Solution. Gabriola Island, British Columbia: New Society Publishers.

Little, J. B. 2009. The Ogallala Aquifer: Saving a vital U.S. water source. Scientific American Special Edition 19: 32–39. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-ogallala-aquifer/.

Soulé, M. 2020. Voices for Biodiversity: Michael Soule, Grandfather of Conservation Biology. https://voicesforbiodiversity.org/articles/interview-with-michael-soule, accessed September 9, 2020.

Tilman, D. 2012. Biodiversity and environmental sustainability amid human domination of global ecosystems. Daedalus, Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 141: 108–120.

Yinon, Bar-On, R. Philips, and R. Milo. 2018. The biomass distribution on Earth. PNAS 115: 6506–6511.

Read Next

What We Have and What We Need

As we reach the end of the 26th volume of the International Journal of Wilderness, it is worthwhile to reflect on this year that was 2020.

The Preservation Paradox: How to Manage Cultural Resources in Wilderness? An Example from the National Park Service

At the same time that federal agencies must comply with protection measures of the Wilderness Act, federal cultural resource laws require agencies to take into account the effects of federal undertakings on cultural resources.

Good News: Wilderness Is Not a Victim of Our Current Intense Political Partisanship

As for intense political partisanships, it is a fact of life in our politics and will always be. But it need not high-center progress for wilderness.