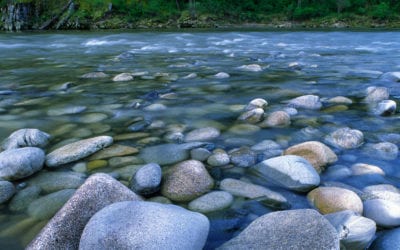

The Wild and Scenic Feather River, CA © Tim Palmer

#TheRiverisMyOffice

Communication & Education

April 2019 | Volume 25, Number 1

Millions of people visit rivers to wade in the water, skip a stone, fish, float, or simply walk alongside them, enjoying the view. However, how do visitors think about the role of their hosts – the river managers or park rangers from town, county, state, or federal agencies who know the river well and provide facilities and information, who make their visit easy and perhaps nearly effortless? These professionals welcome all guests, understanding that they include the enthusiasts who prepare for unanticipated weather and water levels, and the groups of friends who decide to float the river on a hot sunny day with their beverage coolers, and without life vests.

River professionals uphold ideals and values. They greet the challenge of a new or high-water stage river run with grins. They tolerate the tedium of managing regulations, counting people, monitoring invertebrates, or collecting water samples. They are knowledgeable planners whose commitment to rivers is grounded in their expertise and care necessary to manage rivers wisely. They also find joy when helping a nine-year-old cast for her first fish or take out after his first kayaking trip. They know the experience of adventure is personal and that a half-day float may inspire lifelong passion.

Telling the Story

The River Management Society (RMS) is the nation’s only organization dedicated to “support professionals who study, protect, and manage North America’s rivers.” It is rooted in the 1970s when the Interagency Whitewater Committee, river planners, and rangers from US federal river administering agencies collaborated to address the high impact on river campsites and access areas emerging from the growing popularity of river running. Since those early days, river use has continued to grow and diversify, and agency managers have continued to provide a critical interface for the public by welcoming visitors, encouraging them to learn how to run rivers safely, and providing information that teaches them how to care for the rivers they enjoy. Agencies cannot support visitation alone or identically as their missions differ in how they value recreation and river protection. It therefore “takes a village” to manage our rivers and streams, and RMS’s membership and programs reflect this need for collaboration among river outfitters and guides, rangers, planners and landscape architects, environmental lawyers, geologists and fluvial geomorphologists, professors, students, researchers, and authors.

In 2017, the River Management Society decided to recognize the unheralded and, arguably, increasingly undervalued experience of river professionals. As advocates, professionals, and recreationalists ourselves, we were concerned that the role of technical river experts, entrusted with the public’s safety and enjoyment on the nation’s rivers, was being overlooked. To shine a light on their energy and expertise, we quite simply sought to ask river managers and stewards to share a bit about what they do to document glimpses into their day-to-day activities and to help establish how river managers, along with partners in the nonprofit sector and among stewardship-minded businesses make the positive public experience of rivers’ wonders possible.

Anniversaries are markers of important events and can be superb reminders about circumstances that have evolved during ensuing years. The advent of the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act stirred interest in the historic system among both river advocates whose efforts drove its legislative pursuit, and agencies responsible for managing the special values for which the rivers are designated. Commemoration of the act also created an opportunity to define the work of the people whose work makes rivers accessible and to help the public understand the commitment they have made to their profession, their river, and those who visit to work, study, or play.

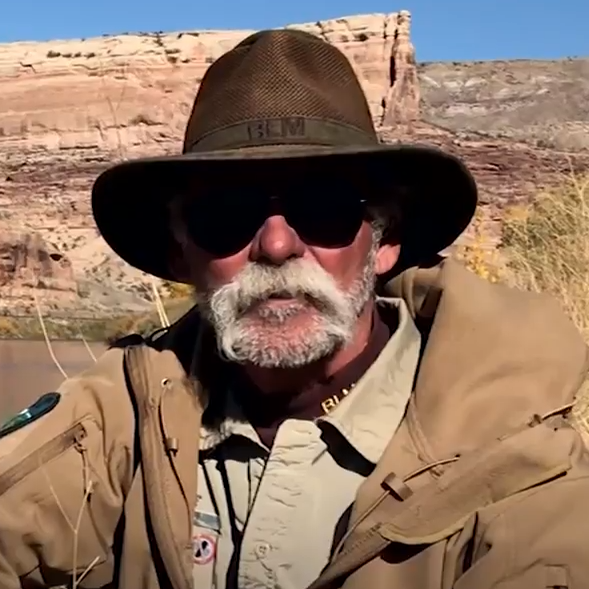

We invited river professionals, colleagues, and friends to “hold up their phone” and record a video of themselves at work sharing what they do, why it is important, and how they would advise others considering a professional position or career in river management and protection. Participants were asked to share their “typical” day, how their efforts benefit and impact the public, and to address issues and challenges faced while managing river resources. Participants were also asked to share a more personal and intimate side of their profession. They were encouraged to describe the moment they knew they wanted to dedicate their careers to stewardship and protection, and what they wished they had known before beginning their professional journey.

Staff from the RMS assisted potential participants by providing guidance for creating videos and uploading content. We could not predict the type and quality of responses we would receive and did not seek to limit or constrain their responses. We had hopes for the messaging we would see and hear and have been thrilled to have collected stories, which have exceeded our expectations! The RMS continues to gather, post, and share river professionals’ stories to raise awareness of the people responsible for river management and the pride they have in their work. They cannot be effective if faceless, so although videos of them all cannot be collected, our efforts are to best represent them all with stories and thoughts that represent both their successes and challenges.

Early in the process, Troy Schnurr and Kathy Zerkle, river rangers for the Bureau of Land Management on the Colorado River and New River, respectively, provided strong examples of how video “selfies” could highlight the efforts and passions of river professionals. Chris Brown, the longtime face for rivers at American Rivers, the National Park Service, and USDA Forest Service, also provided an example of how river stewards and advocates can impact the public. Brown led campaigns to protect more than 1,000 river miles (1,609 km), secure US$25 million in appropriations, and break the congressional logjam on wild and scenic river designations for American rivers in the mid- 1980s.

Many important stories needed to be told, so we proceeded to record profiles during river and paddling events. The result thus far is a compilation of more than 30 short videos featuring a diversity of themes and locations, including

- Rebecca Urbanczyk, David Michaels, and Bob Stanley addressing the protection and management of rivers such as the Clearwater River (ID) and Tuolumne River (CA).

- Kelsey Bracewell, American Canoe Association, discussing the importance and value of teaching and training paddlesport instructors.

- Lil Colby, co-owner of MIT Watergear, and Phil Walczynski, owner of Down River Equipment, highlighting the role and partnerships with manufacturers, businesses, and managers.

- Tabitha Chlubicki and Will Jarvis, Sheri Griffith River Expeditions, sharing their experiences guiding the public through river canyons such as on the Yampa River; and

- Corita Waters, National Park Service, expressing the need to coordinate partnerships among river groups to expand opportunities to experience, and hopefully learn to love, rivers.

We also produced a short compilation video so of select interviews that tells the story of partnerships, efforts, and experience of river advocates, professionals, and county, state, and federal river managers better than anyone could ever script. The #TheRiverismyOffice project playlist can be found online at #TheRiverismyOffice project playlist.

River ranger on the Ruby Horsethief section of the Colorado River

BLM river ranger Rebecca and the Clearwater River cleanup crew in the field on National Public Lands Day, 2018.

Learn from this veteran guide why showing people places is vital to their protection.

Why Shine This Light on Professionals?

The demand to visit outdoor spaces such as rivers and other managed public resources is growing. According to the Outdoor Foundation, whose annual outdoor participation report identifies usage trends for manufacturers of outdoor gear and the public, has shared that outdoor participation continues to grow. In their most recent report, outdoor participation increased from 48.8% of the US population in 2016 to 49.0% in 2017. Participation in human-powered watersports including canoeing, kayaking, and rafting have grown steadily for more than a decade from 7.8% of the population in 2007 to 10.5% in 2017 (Outdoor Foundation 2018). A total of US$887 billion is spent annually to experience the outdoors, supporting 7.6 million jobs. States including Colorado, Utah, and Washington have created high-level positions charged with both supporting the outdoor industry and improving outdoor recreation opportunities.

The US Forest Service, in its long-term monitoring of recreation trends, projected in 2014 continued growth of outdoor participation through 2030. For most outdoor pursuits (excluding hunting, motorized off-road use, and motorized snow use), adult participation days of outdoor activities are projected to grow 21–34% between 2009 and 2030 (White et al. 2014). Despite these trends, available sources and designated responsibility for river management are failing within organizations. Public resource organizations have dismantled the systems that once generously invited, trained, and mentored today’s staff and tomorrow’s leaders. For example, the National Park Service has seen visitation increase 21% from 2013 to 2017, but at the same time, their staffing has been reduced from 27,000 to 22,000, including nearly 40% of seasonal staff who are critical for hosting surges of visitation on busy summer days (Headwater Economics 2019). The result can have dismal consequences, such as

- Visitors greeted by deteriorating buildings, or not enough staff to answer questions, process requests, or provide services.

- Managed spaces suffering without staff to keep toilets and facilities serviced, campgrounds clean and supervised, or with safety and law enforcement services in place and present.

- Visitors rarely seeing a ranger or interpreter to ask questions about the unit or river they are visiting.

Unlike in past years, field staff are called upon to attend to increased administrative duties and take on different roles, many of which were formerly assigned to administrative support staff and additional resources. Whereas generalists could address a diversity of issues and concerns in the past, staff now must attend training two to three weeks per year to certify in specialty and niche areas. Some of these areas, such as security and risk management, represent emerging and new concerns for river professionals.

The “Entry” End of Staffing

Federal agencies have been trimming staff as a percentage of the population for decades, and significant state attrition shows the trimming is not slowing. River management positions continue to decrease as a changed valuation of technical, entrepreneurial, and resourceful attributes in staff appears to be occurring across agencies. Thus, entry-level staffing exists in very few locations and has been replaced largely by collaborations with external groups and partners. These partnerships include enthusiastic young people recruited and managed by robust youth work programs. In the past, youth would be led by seasoned professionals. Too often now, these volunteers are on their own, with minimal supervision and no one to mentor them. Recruits are appreciated by agencies for providing excellent sources of low-cost labor, but few are able to remain in the agency through developed programs that allow direct hiring.

Despite these challenges, several programs continue to have a positive impact on river conservation and stewardship. The Corps Network is the National Association of Service and Conservation Corps. A total of 130 Corps operate across the country and participate in projects on public lands and in rural and urban communities. Other national organizational partners include the Student Conservation Association and AmeriCorps. Each of these partners provides opportunities for internships, field experience, and exposure to agency management and activities. In addition, the Pathways Program is a federal service program that enables managers to hire students and interns, including Presidential Management Fellows, and hire them directly for positions thereafter.

Challenges also exist with skilled seasonal staff. Seasonal employees who return each year continue to fill agency ranks, but their days are arguably numbered. For many years, individuals and partners have worked as “double seasonals,” spending summers in one park, winters in another. Working as a double seasonal has allowed them to maintain a unique professional lifestyle and enable the federal agency to staff reliable returnees. However, Rule 1039 (National Park Service 2018) implemented in 2018 deemed such employees ineligible to be rehired. Positions once staffed for six months are now eight months long. One person may not be able to work that entire time, supervisors are not going to hire two people, and the unit may be short-staffed during a period of peak visitation. Mass retirement of individuals in the baby boomer generation is leaving tremendous experience gaps. There are capacity issues related to programmed mentoring by experienced veterans, leaving glaring gaps in their representation in processes that cannot be picked up easily or learned quickly by young professionals and new practitioners. Making matters worse, retirees are being hired as consultants to plug the experience gaps created by their departure instead of being asked to train, acclimate, and mentor colleagues before their retirement from the agencies.

Each of these situations can place pressure upon up-and-coming river professionals. Many well-regarded individuals who have gathered experience are on track to grow, lead, and create success for their organizations. They are keen to shoulder responsibility, but they are asked to (1) fill positions emptied by retirees, (2) cover for underperforming or understaffed programs, (3) attend training sessions for further professional development, and (4) request to address river management responsibilities once held as high priorities but now viewed as collateral duties. For example, field offices can severely reduce seasonal positions, and can be extremely slow to replace permanent staff. One example involves a seasoned manager who was responsible for 21 seasonal staff and volunteers on one of the largest river programs in the country and decided to relocate to another organization. Following the person’s departure and nearly three years later, the current program lead has similar responsibilities but is supported by only five seasonal employees. Funds freed up by the vacancy and river position reclassifications were redeployed to support other programs.

Agencies such as the National Park Service (NPS) and other river management agencies are also being asked to respond to Secretarial Order 3366 (US Department of the Interior 2018), which pushes the agencies to increase recreation opportunities on public lands and waters managed by the US Department of the Interior. In seeking feedback to identify priority issues and their capacity to meet their needs, the NPS identified human resources, staffing, ability to address maintenance needs, and the capacity to engage administrative partners as key issues. They cite having to take on significant responsibility as collateral to their primary duties and the increased reliance on volunteers as issues needing attention.

We cannot forget that those who work on the river understand their program and resource needs. As a river campground or access launch site experiences higher use levels or needs attention due to disrepair, it is the river management professionals who are best prepared to address concerns. You have met #theriverismyoffice river managers and others who work in river-related professions. Their stories paint a picture of a richly committed, enthusiastic group of people responsible for many aspects of the rivers on or in which we rely. This awareness alone is a significant achievement. In the midst of today’s movement to “support public lands,” keep in mind that rivers belong to the public too and are not always included in the discussion. A river running through a county park or a national monument relies on river managers and planners working with scientists, outfitters, or community partners to serve you when you visit. Rivers provide our priceless resource. People determine whether they maintain their value and health.

This is the beginning of a discussion, and RMS seeks input on the importance of the support for professional river staff, their expertise, and their leadership as critical to the future stewardship of our rivers and their public access. We feel it is important to speak on behalf of river managers to those who are in a position to hire, mentor, and develop leadership among their currently dwindling ranks. We welcome suggestions about how best to build upon these stories, crafting of an argument supporting the protection of this profession.

Acknowledgments

Many people contributed their time, professional experience, and love for rivers to this conversation in addition to our video selfie contributors. Thank you to our documentary producer Nina Ignaczak and the RMS board members who have allowed me to pursue this initiative. I especially thank Ben Alexander, Herm Hoops, Patti Klein, Martin Hudson, Molly MacGregor, Gary Marsh, Bob Ratcliffe, Lynette Ripley, and Krista Sherwood, Bob Dvorak, and Patagonia for your support as we begin a journey.

RISA SHIMODA is a problem solver, marketer, and advocate for the programs, staff, members, and board of the River Management Society, for which she serves as the executive director. An avid whitewater paddler, Risa cofounded the Outdoor Alliance and has served on the boards of the Conservation Alliance, North American Paddlesports Association, International Whitewater Hall of Fame, and Nantahala Outdoor Center; email: executivedirector@river-management.org.

The RMS is a nonprofit 501(c)3 organization that provides technical assistance and support on a variety of topics for river professionals – water trails, hydropower relicensing, the only national river recreation database in North America, interface between students and river professionals through selected colleges and universities, professional training, and management symposiums.

References

Headwaters Economics. 2019. Economic impact of national parks. Retrieved January 2019 from https://headwaterseconomics.org/public-lands/protected-lands/economic-impact-of-national-parks/.

National Park Service. 2018. Changes to temporary seasonal hiring. Retrieved January 2019 from https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/temporary-appointment-changes.htm.

Outdoor Foundation. 2018. Outdoor participation report for 2018. Retrieved January 2019 from https://outdoorindustry.org/resource/2018-outdoor-participation-report/.

US Department of the Interior. 2018. Secretarial Order 3366. Increasing recreational opportunities on lands and waters managed by the U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved January 2019 from https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/so_recreation_opps.pdf.

White, E. M., J. M. Bowker, A. E. Askew, L. L. Langner, J. R. Arnold, and D. B. K. English. 2014. Federal outdoor recreation trends: Effects on economic opportunities. National Center for Natural Resources Economic Research (NCNRER). NCNRER Working Paper Number 1, October. Retrieved from https://www.fs.fed.us/research/docs/outdoor-recreation/ficor_2014_rec_trends_economic_opportunities.pdf.

Read Next

Personal Restraint and Responsibility for Protected Areas in Crisis

“How can a society champion the public good in one instance, and yet willfully damage and undermine that same good in another?”

Wilderness Was Not America’s New Idea: Exploring a New Wilderness Stewardship Ideal at the 2018 National Wilderness Workshop

As tribes across the United States seek to regain their sovereignty and access to ancestral lands and ecosystems, we as managers can be visionary and create a management model that extends beyond a seat at the table.

Did #MakeYourSplash Make a Splash?

In 2018, we celebrated the 50th anniversary of the birth of our Wild and Scenic River System. Created in 1968 with only eight rivers, the system has grown to include more than 12,000 miles (19, 312 km) and over 200 protected rivers.