Hiker on the Tonto Trail. Photo credit © Will Rice.

“On the Staff of the Grand Canyon”: Assessing Manager and Stakeholder Perspectives on Sustainable Wilderness Visitor Use Management

Science & Research

April 2021 | Volume 27, Number 1

PEER REVIEWED

ABSTRACT

Overall visitation to Grand Canyon National Park (GRCA) grew 36%, and backcountry overnight visits increased 8% from 2010 to 2019. This research examines how park managers and other key stakeholders, such as park-partner staff, are managing increasing visitation levels. In total, 36 semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted with park managers and other key stakeholders during the summer of 2019. This study aims to inform sustainable visitor use management at GRCA and other wildland protected areas by examining the social, physical, and managerial considerations described by respondents. Results demonstrate both immediate and long-term operational issues and constraints for park management stemming from increasing frontcountry and backcountry recreational use.

Standing on the rim of the Grand Canyon in 1937, British author J. B. Priestley mused, “If I were an American, I should make my remembrance of it the final test of men, art, and policies. I should ask myself: Is this good enough to exist in the same country as the Canyon?” (p. 285). Priestley concludes that “every member or officer of the Federal Government ought to remind [themselves], with triumphant pride, that [they are] on the staff of the Grand Canyon” (1937, p. 285). The Grand Canyon is a geologic marvel that has long-standing indigenous importance and has drawn considerable global interest over the last century. Following its designation as a national park in 1919, with seldom exception, Grand Canyon National Park (GRCA) annual visitation has persistently grown, with a markedly frenetic increase in the past decade. Between 2010 and 2019, visitation increased by 36%, rising to nearly 6 million visits annually (National Park Service 2020). Therefore, to be on the “staff of the Grand Canyon” is not quite as romantic as Priestley might presume. As illustrated in research at other national parks undergoing similar visitation surges, managers must ensure the preservation of visitor experiences in concert with the resources through which they are facilitated (Manning 2007).

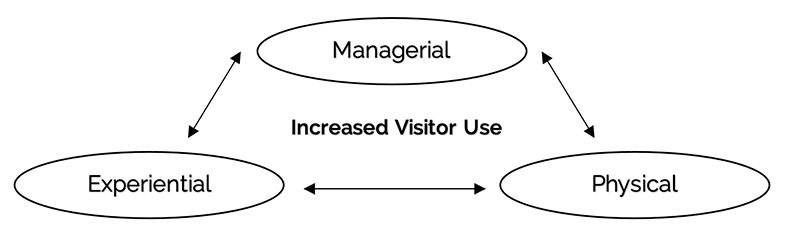

As visitation continues to increase at GRCA, further managerial attention is needed to appropriately balance recreation use and preservation – considering both ecological and experiential issues when making management decisions (Driver and Brown 1978). Manning (2007) presents a conceptual framework for managing visitor capacity in protected areas composed of three dimensions: physical, experiential, and managerial (Figure 1). The intent of this framework is to strike a balance between physical, experiential, and managerial sustainability. In this way, the recreation experience, park resources, and managerial services can be “maintained or even enhanced in the face of increasing use” (Manning 2007, p. 21).

Figure 1 -A conceptual framework with the three dimensions of sustainable management of increased wildland visitor use management (adapted from Manning 2007).

The three dimensions (physical, experiential, and managerial) that comprise the conceptual basis for protected area management were first established by Driver and Brown (1978). The physical dimension includes the natural and cultural resources that facilitate recreation and is limited only to those resources that managers can control (Cole 2004). The experiential dimension encompasses all aspects of the visitor experience including motivations, experiences, and outcomes – both positive and negative (Driver 2008). The managerial dimension includes all legal mandates, facilities, staff, and financial resources that govern and support a protected area (Manning 2007).

Evaluation of the wildland visitor experience has enhanced our understanding of the interconnectedness of these three dimensions (e.g., Manning 2011; Monz 2009). However, there remains a dearth of understanding regarding how those individuals that are charged with carrying out sustainable management – namely, park managers, concessionaires, tour operators, and nonprofit park partners – conceptualize the interplay of these dimensions and the role each plays in wilderness management. It is thus the purpose of this study to examine how those that manage GRCA address increased wildland visitation. Principally, this includes an investigation to identify key stakeholders’ perspectives on issues, constraints, and possible solutions to sustainably manage visitor use across the three dimensions of sustainable wildland management at GRCA, and examine the interactions between dimensions in both frontcountry and backcountry settings.

Methods

Study Area

Grand Canyon National Park encompasses most of the 446-kilometer (277-mile) Grand Canyon of the Colorado River – a UNESCO World Heritage site—in northern Arizona, USA. Ninety percent of the park is proposed as federally designated wilderness and is managed as such (Moore and Witt 2018). Backcountry visitation to GRCA is primarily concentrated in a relatively small area – the Colorado River and the Bright Angel-Kaibab Trail Corridor. During the past decade, backcountry overnights within GRCA increased 8% to 320,032 in 2019 (National Park Service 2020). A long-term study on a sample of backcountry camping areas found that the number of visitor-made backcountry campsites more than doubled between 1984 and 2005, resulting in vegetation impacts (Cole et al. 2008). Additionally, Pettengill (2016) notes that an overall increase in park visitation and backcountry day use has resulted in increases in unprepared hikers and search-and-rescue responses. While permitting and zoning of backpacking and river trips in the park allows for overnight capacity management, day use management in backcountry and frontcountry areas currently lacks such levers for controlling volume and distributing use.

Semistructured Interviews

To address potential issues, constraints, and solutions regarding sustainable visitor use management at GRCA, onsite semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted with National Park Service (NPS) employees and other key stakeholders throughout July 2019. Interviews were conducted in-person and by telephone with individuals identified by GRCA’s Visitor Use Management Team. Additional respondents were identified via snowball sampling, following the methods of Garcia et al. (2018). Interview respondents were sought from all organizational divisions of GRCA (administration, interpretation, law enforcement and visitor protection, maintenance, planning and special projects, and resource management) and key park stakeholder groups (e.g., tour guides, concessionaire operators, and nonprofit park partners).

Only two researchers conducted interviews to maintain consistency. Interviews ranged from approximately 9 to 50 minutes, and all were digitally recorded. The interview consisted of 10 primary questions related to visitor use issues, managerial constraints, and possible solutions. All interviews began by asking respondents about the overarching visitor use management issues facing GRCA and then transitioned into asking about specific visitor use trends and management approaches to address these trends in both frontcountry and backcountry settings. As the interviews progressed, respondents were asked to discuss operational constraints and potential solutions.

Analysis

The recorded interviews were transcribed and inductively coded following the guidance of Rubin and Rubin (2012). While general thematic categories of social, physical, and managerial considerations were pre-established, underlying codes and categories were derived inductively through interaction with the data (Charmaz 1996; Rubin & Rubin 2012). Coding of themes was completed individually by members of the research team, and then collaborative sessions were held to establish intercoder reliability.

Results

In total, 36 interviews were conducted with NPS staff (29 interviewees) and key park operations stakeholders (7 interviewees). Average length of employment as a member of the NPS staff at GRCA or a partnering organization was 12 years, with tenures ranging from less than 1 year to a maximum of 38 years. Given the goal of this study, analysis and intercoder consultation yielded themes of issues, associated constraints, and possible solutions related to each of the three components of sustainable visitor use management – managerial, physical, and experiential dimensions (Driver and Brown 1978; Manning 2007). The identified recurring themes illuminate issues and solutions related to staffing, infrastructure, resource degradation, wildlife habituation, crowding, and displacement. The results that follow are presented for each of the three dimensions of sustainable visitor use management in the sequence of potential issues and constraints, and solutions, highlighted through key quotes from the respondents.

Managerial Dimension

Within the managerial dimension, themes emerged concerning the need for both improved policy and communication of existing policy. Additionally, concerns about sustainable levels of staffing were prominent.

Issues and Constraints

When asked to identify visitor use management issues facing GRCA, many respondents reported concerns with visitor capacities:

“Ultimately, all of this ties back to the capacity and managing towards the desired conditions and the associated visitor capacity of the park. And that’s something that is an unknown right now.” – Respondent 2

To this end, others mentioned the lack of conceptualized and quantifiable day-use carrying capacity indicators and standards (Manning 2011):

“From a broad perspective, there’s just no concept of capacity. We don’t have anything quantifying that, so what can we sustain here long-term?” – Respondent 26

Unlike NPS staff, concessionaire operators are not directly bound by a mandate of preservation. Respondents noted the conflicting missions of the NPS and concessionaires:

“The concessionaires want more people, they never want fewer people, they always want more people … they don’t have a visitation cap.” – Respondent 3

Aging backcountry infrastructure (e.g., the transcanyon water distribution pipeline, hiking and stock bridges, etc.) was also explicitly mentioned as being problematic, as was the ability to manage the volume of waste associated with increased visitor use:

“Some utility infrastructure issues that are developing and I don’t even know necessarily if it is the visitor use creating that problem or if it’s just age of infrastructure … there’s a tremendous maintenance backlog in the park.” – Respondent 28

“The compost toilets in the inner canyon, we have this discussion internally, they’re not technically compost toilets because they get hit so hard and so aggressively … they can’t actually compost because of the volume they’re receiving.” – Respondent 30

When asked about present operational constraints, many respondents cited staffing. Other respondents connected the issues of aging infrastructure to the shortage of staff:

“Even though we have 6 million people coming here, it seems like there’s about 12 people trying to keep this park together, because we have no staff and no money. And the pipeline [that carries drinking water through the canyon along the Bright Angel and North Kaibab trails] is always breaking. And we’re always like, on the verge of not having any water, and there’s no one to fix it.” – Respondent 3

While mentioning operational constraints, one respondent highlighted the relationship between the physical, managerial, and experiential dimensions by citing elements related to the mission of the park:

“We’ve got to be able to make that case [for any future visitation policies] in terms of the mission of the park, we’ve got to present it from both a resource stewardship perspective, but also visitor experience…. How is what we’re going to do going to improve the visitor experience, even if it has some impacts that might be seen otherwise?” – Respondent 5

Solutions

Respondents referenced several potential contributions of the managerial dimension toward more sustainable wildland visitor use management, namely by way of potential policy changes and increasing staffing. The theme for more backcountry regulation and the communication of regulations through education was highly salient:

“There is a community that know the rules and regs and they do it [packraft] by the books and they’re pretty bad ass people. So it’s the regulations and it’s still kind of getting worked out with the superintendent’s compendium…. It is really kind of [to] help put it in more black and white.” – Respondent 6

Additionally, respondents voiced the need for more staffing to handle increased use in both the frontcountry and backcountry:

“If you have more staff out there to help direct visitors, maybe it would reduce the impact to resources.” – Respondent 2

Other solutions were directly related to concessionaire operators and tour companies (e.g., operators of the backcountry lodging at Phantom Ranch, backpacking outfitters, frontcountry hoteliers, etc.), and emphasized the importance of partnerships and communication:

“I think it’s important that we work closer with tour companies to help them understand why we do the things we do and help get them on board with the park mission.” – Respondent 5

“I think a lot of it is education [of concessionaires].” – Respondent 13

Physical Dimension

The physical impacts of increased wilderness recreation within GRCA are well-documented (see Cole et al. 2008). Therefore, unsurprisingly, respondents’ perspectives within the physical dimension were centered around recreation’s impacts on natural and cultural resources in the backcountry of GRCA, predominantly proposed as wilderness (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Ecological degradation from recreation use on Cedar Ridge along the South Kaibab Trail. Photo by Will Rice.

Issues and Constraints

In addition to citing broad recreation impacts to park resources, many respondents mentioned specific sources and impacts of ecological degradation including social trails, wildlife habituation, and waste:

“We have social trails, you know, where people just kind of create like the quickest way to get to [a desired location].… And I feel like once those social trails are created, it’s really hard to get people to stop using those as areas.” – Respondent 23

“Elk, in particular, are very habituated and they let themselves get pet sometimes. And, you know, that creates problems, particularly around calving and rutting season…. We’ve had people gored. Squirrels are a big problem too, obviously.” – Respondent 24

“We see impact areas to resources. And in a lot of, it happens here at the South Rim for sure. You know, they’re gathering firewood, they’re trotting in areas where they shouldn’t be – down trail I’m thinking specifically – not utilizing the bathrooms, and pooping in places they shouldn’t be, going off trail, leaving trash behind.” – Respondent 4

Another emergent theme concerning the physical dimension was wilderness recreation’s impacts on cultural resources:

“There’s also a ton of cultural resources, too, that are in danger with so many people in the park –especially when they get into the backcountry areas…. [We must] try to be realistic about matching access with available areas for people, so that they’re not having to camp outside of boundaries or do damage to resources that we’re trying to protect.” – Respondent 27

“The biggest issues for us are adverse effects to cultural resources. And those can be archeological sites, historic buildings, cultural landscapes, ethnographic resources, plants, animals, insects, minerals, geological features, a whole range of things…. There’s an entitlement that they can go where they want to go and do what they want to do without that awareness that their actions have consequences.” – Respondent 36

Tied closely to recreation’s impacts on the physical dimension was the acknowledgment that the NPS has experienced a number of constraints toward their monitoring efforts:

“What we’re seeing is resource impacts that we don’t have systems in place to monitor effectively because we don’t have the money or the staff to do that.” – Respondent 27

Solutions

Respondents offered several potential solutions to both preserve resources and restore degraded resources. The most salient management strategy included developing a parkwide, systems approach to carrying capacity, which does not currently exist:

“Reduce the visitation to the park on a daily and yearly basis. You wouldn’t have to necessarily have a cost associated with getting a reservation to come visit the Grand Canyon, but it has a carrying capacity and we have exceeded that carrying capacity and we need to deal with that.” – Respondent 36

“One of the best solutions that we could look at is carrying capacity of the park and if we needed to shift demand management or timed entry … to make sure that people are visiting areas of the park in numbers that can sustain those visitors.” – Respondent 27

For the issues of social trailing and wildlife habituation, respondents advocated for more indirect solutions (Figure 4):

“[Concerning social trailing] we have the ability to plant prickly pear or cactus in areas that we don’t really want people to walk in. That actually does work really well.” – Respondent 23

“For me, the biggest issue is really that we have a very uneducated visitor as far as wildlife goes. Who then thinks they’re at a petting zoo… A lot of it is trying to educate.” – Respondent 24

Figure 4 – A squirrel gets a food reward from a hiker along the North Kaibab Trail. Photo by Clay Larsen.

Experiential

Respondents’ perspectives concerning the experiential dimension centered on the impacts of dense visitor use in popular areas, primarily in the South Rim area of GRCA. Themes of crowding and displacement were salient across interviews.

Issues and Constraints

Respondents perceived crowding to be a significant experiential issue arising from increased visitor use. This theme of crowding was tied to the findings suggesting potential perceived failure to provide visitors with the “national park experience” in both frontcountry and backcountry settings, from some respondent perspectives:

“To some degree even things like viewpoints, you know, some of the sites – and Mather, Yaki, Hopi – they get so crowded with people, I worry that we’re not offering them the experience that they should get in a national park.” – Respondent 33

“I mean, places are busier. It’s harder to find a place where you can get away from it all.”– Respondent 24

“[The visitor] is not receiving that National Park Service experience that you would hope for when you come to a park, and that’s really hard.”– Respondent 1

Displacement was another salient theme that arose in this dimension. Respondents perceive that increased use on popular trails (Bright Angel and South Kaibab) are pushing visitors into more remote areas and less traveled trails to find solitude:

“So the demand is so much higher. And it probably forces a lot of people not to do the popular hikes and just try to get away. And then that expands into other areas that don’t normally see that amount of people.”– Respondent 13

Solutions

To mitigate the experiential issues arising from increased visitor use, respondents again referenced establishing systematic day-use carrying capacities, but also underscored the importance of managing visitor expectations to meet present conditions. Two themes emerged in this area. First, proactive management was seen as a means of managing expectations of use levels before visitors’ arrival:

“Just educating folks before they get here about what to expect. Whether they come the week of 4th of July or the week of February 2nd or sometime when there’s some of our lowest visitation. So I think there’s an education component that can really manage visitation a little bit.” – Respondent 10

Second, reactive management was seen as a means of managing expectations in situ:

“We have this army of volunteers supported by a small cadre of summer seasonal employees led by a permanent position that goes out and teaches people how not to be miserable in their national park. So, in certain pieces, we can educate our way out of crowding.” – Respondent 9

Discussion and Implications for Management

In addition to addressing the managerial, physical, and experiential dimensions individually, it is important to discuss how they interact. The relation and required balance between these three aspects of the setting is necessary to fulfill the fundamental three-dimension sustainability framework (Manning 2007). The importance of considering the interconnectedness of the three dimensions was evident through a response given by one respondent:

“When we were first implementing shuttle systems in the Park Service, we just implemented them and didn’t really think about the associated impact to the trails and the visitor experience and crowding. That’s what is happening when you have these large shuttle buses that are dropping off people at very defined spaces. And what happens to the resources that they experience after that?.. .What happens on pavement translates to what happens off-pavement.” – Respondent 2

This form of systems thinking was an emergent theme within our study. Sustained increases in visitor use are forcing key stakeholders at GRCA to consider systematic linkages, as further highlighted through the three dimensions of protected area management. Due to this perspective, respondents largely felt that they could identify solutions to the complex problems they are facing, but in some instances, park units do not have the resources to fully implement these solutions.

Sustained increases in visitor use are forcing key stakeholders at GRCA to consider systematic linkages, as further highlighted through the three dimensions of protected area management.

Broader Impacts

The management of national parks has grown more and more complex in the context of a global economy where we are all intertwined with one another. This article shows the importance of systems thinking and that managers acknowledge that sustainable solutions exist in a social-ecological context. However, as park issues have become more complex, and science more advanced, how has the NPS institutional structure changed over the past 100 years? Solutions today demand integrated systems thinking and teamwork, and yet most park managers work in teams called “divisions.” Future work should explore how the architecture of the NPS organization may hinder a systems approach to sustainable solutions (Figure 5).

Respondents’ wide support for carrying capacity-related actions largely follows McCool and Lime’s (2001) position that this tactic is a popular solution among managers. Setting wildland recreation capacities can be a rather straightforward process including measurements of all three dimensions of the recreation setting. Therein lies its appeal. The authors posit that carrying capacity’s continued popularity among managers “may be because of its apparent scientific objectivity and simplicity” (McCool & Lime 2001, p. 380). Yet, a host of critiques have been made against the concept in recent decades—chiefly that it represents a simplistic view of reality that fails to sufficiently account for recreationists’ behaviors (McCool and Lime 2001). Additionally, from the visitor perspective, carrying capacities are often less favorably viewed as they tend to restrict freedom (McCool and Lime 1989). However, as noted by Ponting and O’Brien (2015), establishing recreational carrying capacities that fully integrate the physical and managerial dimensions – not solely the experiential dimension – can be effective as one component of a larger strategy to manage increased use. Our findings show that park-level managers at GRCA understand the role of carrying capacities as exactly that – one part of the larger visitor use management equation.

Figure 5 – Backcountry day users wait to find shade and fill water bottles at Indian Gardens along the Bright Angel Trail in October 2020. Photo courtesy of NPS/K. Pitts.

Although carrying capacity was the most universally proposed solution to manage increased wilderness recreation at GRCA, education was also a highly salient theme. Education is the most widely applied form of indirect visitor use management (Manning and Lime 2000). Looking across the three dimensions, we find that education was proposed to (1) manage behavior, (2) manage expectations in situ, and (3) manage expectations prior to visiting GRCA. All three approaches are perceived as plausible means of facilitating backcountry visitor use in a manner that adheres to management objectives. These tactics are very much in line with the strategies recommended by previous research to manage visitor expectations in high-use backcountry areas that are managed as wilderness (e.g., Rice et al. 2020; Taff et al. 2015, 2019). For example, Armstrong and Kern (2011) recommend communication with visitors prior to and during visitation to change perceptions of what to expect at densely used areas of a park and how visitors should react to crowded conditions. These types of approaches have been applied in GRCA through a number of strategies, including encouraging visitor behaviors that align with park management objectives through social media and onsite signs (Pettengill 2016), and should continue to be implemented and tested for effectiveness in GRCA.

Figure 6 – AJ Lapre, branch chief of interpretation, stands at a memorial service for a deceased ranger on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon in February 2020. Photo courtesy of NPS/M. Quinn

The broader results of this research underscore the importance of understanding managers’ perspectives of visitor use trends – in concert with collecting data on visitor perceptions and resource conditions. In a theoretical sense, adding managerial perspectives completes the conceptual framework of sustainable visitor use management (Figure 1). However, our data revealed a more “practical” finding: managers and park partner organizations not only maintain and steward park resources, but they too, are park resources. Not only do they provide the face and voice of parks and protected areas, but they also endure very real impacts from increased visitor use and shifting recreation trends – as evidenced in our interviews:

“Things are fine, adequate, moving up. [The] Park Service, I think, is extremely limited in capacity and trying to support a lot of the operations. We’re really holding things together with duct tape and bubble gum sometimes.” – Respondent 34

“And getting paid in sunsets only lasts for so long.” – Respondent 3

As Stephen Mather – the first director of the NPS – professed, “No picture of the national parks is complete unless it includes the rangers” (1928, p. vii). In this spirit, it is imperative that managers themselves are considered in future wildland protected area research and as part of the managerial dimension of sustainable wildland management – along with the services they provide (Figure 6). Additionally, the well-being of wildland managers merits future research, as much is still unknown concerning what is required of those who serve “on the staff of the Grand Canyon” (Priestley 1937, p. 285).

Author Note

Funding for this research was provided through a Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit Agreement with Grand Canyon National Park.

WILLIAM RICE is an assistant professor at University of Montana, Parks, Tourism, and Recreation Management Program; email: will.rice@mso.umt.edu.

OAKES SPIVEY is a recent graduate of the Pennsylvania State University Department of Recreation, Park and Tourism Management; email; ors5029@psu.edu

PETER NEWMAN is department head and professor in the Pennsylvania State University Department of Recreation, Park and Tourism Management; email; pbn3@psu.edu.

B. DERRICK TAFF is an assistant professor in the Pennsylvania State University Department of Recreation, Park and Tourism Management; Email; bdt3@psu.edu.

References

Armstrong, K. E., and C. L. Kern. 2011. Demarketing manages visitor demand in the Blue Mountains National Park. Journal of Ecotourism 10(1): 21–37.

Charmaz, K. 1996. The search for meanings: Grounded theory. In Rethinking Methods in Psychology, ed. J. A. Smith, R. Harré, and L. Van Langenhove (pp. 27–49). London: Sage Publications.

Cole, D. N. 2004. Wilderness experiences: What should we be managing for? International Journal of Wilderness 10(3): 25–27.

Cole, D. N., P. Foti, and M. Brown. 2008. Twenty years of change on campsites in the backcountry of Grand Canyon National Park. Environmental Management 41(6): 959–970.

Driver, B. L. 2008. What is outcomes-focused management? In Managing to Optimize the Beneficial Outcomes of Recreation, ed. B. L. Driver (pp. 19–37). State College, PA: Venture Publishing.

Driver, B. L., and P. J. Brown. 1978. The opportunity spectrum concept and behavioural information in outdoor recreation resource supply inventories: A rationale. In Integrated Inventories of Renewable Natural Resources: Proceedings of the Workshop, January 1978, Tucson, Arizona, ed. H. G. Lund, V. J. LaBau, P. F. Ffolilott, and D. W. Robinson (pp. 24–31). Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Ranger Experiment Station.

Garcia, X., M. Benages-Albert, and P. Vall-Casas. 2018. Landscape conflict assessment based on a mixed methods analysis of qualitative PPGIS data. Ecosystem Services 32: 112–124.

Manning, R. E. 2007. Parks and Carrying Capacity: Commons without Tragedy. Washington, DC: Island Press.

———. 2011. Indicators and standards in parks and outdoor recreation. In Quality-of-Life Community Indicators for Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management, ed. M. Budruk, and R. Phillips. Dordrecht, NL: Springer.

Manning, R. E., and D. W. Lime. 2000. Defining and managing the quality of wilderness recreation experiences. In Wilderness Science in a Time of Change Conference – Volume 4: Wilderness Visitors, Experiences, and Visitor Management; 1999 May 23–27; Missoula, Montana, ed. D. N. Cole, S. F. McCool, W. T. Borrie, and J. O’Loughlin (Vol. 4, pp. 13–52). Ogden, UT: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Mather, S. T. 1928. A word of introduction. In “Oh, Ranger!” A Book about the National Parks, ed. H. M. Albright and F. J. Taylor (pp. vii–viii). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

McCool, S. F., and D. W. Lime. 1989. Attitudes of visitors toward outdoor recreation management policy. In Outdoor Recreation Benchmark 1988: Proceedings of the National Outdoor Recreation Forum, Tampa, Florida, January 13–14, 1988, ed. A. E. Watson (pp. 401–411). Asheville, NC: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station.

————. 2001. Tourism carrying capacity: Tempting fantasy or useful reality? Journal of Sustainable Tourism 9(5): 372–388.

Monz, C. A. 2009. Climbers’ attitudes toward recreation resource impacts in the Adirondack Park’s Giant Mountain Wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 15(1): 26–33.

Moore, R., and K. F. Witt. 2018. The Grand Canyon: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

National Park Service. 2020. National Park Service Visitor Use Statistics. Park Reports: Grand Canyon NP.

Pettengill, P. 2016. Understanding extended day use of corridor trails. Park Science 33(1): 84–90.

Ponting, J., and D. O’Brien. 2015. Regulating “Nirvana”: Sustainable surf tourism in a climate of increasing regulation. Sport Management Review 18(1): 99–110.

Priestley, J. B. 1937. Midnight on the Desert: An Excursion into Autobiography During a Winter in America, 1935–36. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Rice, W. L., B. D. Taff, Z. D. Miller, P. Newman, K. Y. Zipp, B. Pan, … A. D’Antonio. 2020. Connecting motivations to outcomes: A study of park visitors’ outcome attainment. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 29: 100272.

Rubin, H. J., and I. S. Rubin. 2012. The first phase of analysis: preparing transcripts and coding data. In Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 2nd ed. (pp. 201–223). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Taff, B. D., D. Weinzimmer, and P. Newman. 2015. Mountaineers’ wilderness experience in Denali National Park and Preserve. International Journal of Wilderness 21(2): 7–15.

Taff, B. D., J. Wimpey, J. Marion, J. Arredondo, F. Meadema, F. Schwartz, B. Lawhon, and C. Dems. 2019. Informing planning and management through visitor experiences in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. International Journal of Wilderness 25(1): 44-56.

Read Next

Protected Areas in a Post-Pandemic World

I am excited that 2021 brings us the 27th volume of the International Journal of Wilderness, and with is comes new beginnings.

Interpreting John Muir’s Legacy

In judging Muir’s legacy, we should be compelled to look inward, admit our own shortcomings, and acknowledge that we, too, have been participants in a system that oppresses Black Americans, Indigenous peoples, and other people of color.

The Curse of the Wild Horses: Deromanticizing Feral Horses to Save Australia’s Kosciuszko National Park

This article documents two walks in the Byadbo Wilderness Area of Australia’s Kosciuszko National Park that revealed inordinate numbers of feral horses, whose population has increased rapidly despite ongoing drought and consequent environmental damage