View of the Great Gulf Wilderness, New Hampshire with Mt. Washington in the background.

Smarter Long-Distance Hike: How Smartphones Shape Information Use and Spatial Decisions on the Appalachian Trail

Communication & Education

August 2020 | Volume 26, Number 2

PEER REVIEWED

ABSTRACT

Smartphones create new opportunities and challenges for managers and recreationists by facilitating novel communications. Through semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 20 Appalachian Trail (AT) long-distance hikers, we explored hikers’ use of information sources, including smartphone-based sources, and spatial decisions. While GPS seemed to be a reassurance tool, user-generated content appeared to play a greater role in decisions related to camping, points of interest, and water sources. Results provide insights on AT long-distance hikers’ experiences and perceptions about smartphones. Findings may also aid mangers and researchers in evaluating the appropriateness of smartphones in protected areas.

Participation in overnight backpacking has been steadily growing in the United States (Outdoor Foundation 2018), and national scenic trails have seen recent surges in popularity. Since the Appalachian Trail’s (AT) completion in the 1930s, nearly 20,000 people have reported hiking at least 2,000 miles (or 3,219 km) of it, but nearly 14,000 of these hikes have been reported since the year 2000 (Appalachian Trail Conservancy [ATC] 2019a). While some of these 2,000-milers are section hikers (i.e., they hiked the whole trail in sections over multiple years), a majority are thru-hikers (i.e., they hiked the entire trail in one year). This growth in long-distance hiking has prompted Fondren and Brinkman (2019) to suggest that “long-distance hiking has captured the zeitgeist or cultural climate of the time” (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Long-distance and day hikers overlooking the Blood Mountain Wilderness, Appalachian Trail, Georgia, USA.

As recreation on national scenic trails increases, impacts on environmental and social conditions require more attention. Recreational use causes biophysical impacts, which can have substantial consequences on ecological integrity and the visitor experience in natural areas and wilderness (Hammit, Cole, & Monz 2015; Manning, Ballinger, Marion, & Roggenbuck 1996). Long-distance hiking is no exception, especially when one considers the amount of time spent in wilderness and protected areas over the course of a long hike. Long-distance hikers may camp 100 or more times on the AT in a single journey. Even when practicing low-impact techniques, camping can be a very impactful activity (Cole & Monz 2004). Different strategies can aid managers in concentrating or dispersing impacts associated with camping (Marion, Arredondo, Wimpey, & Meadema 2018), but their success typically hinges on recreationists following management guidance and locating appropriate campsites.

Managing the areas through which these trails pass involves balancing social and environmental objectives (Daniels & Marion 2006). Land management is complicated on long-distance trails, which often traverse multiple distinct protected areas while also connecting towns or developed rural areas. In the case of the AT, the route traverses 24 wilderness areas in addition to numerous other federal, state, and local protected areas (National Park Service [NPS] 2014). Management of the trail corridor is shared among the various land owners and managers, the ATC, and a federation of 31 volunteer-led trail maintenance organizations (NPS 2014). Managers are faced with the classic conundrum of providing recreational opportunities for today’s visitors while also protecting the natural resources for generations to come, and emerging technologies change the management landscape.

More than two decades ago our colleagues wondered, “Will we be able to feel assured that the next person coming down the trail won’t have a cell phone stashed away in their pack and be able to contact the outside world if an emergency arises? Will people still elect not to bring their cell phones along?” (Freimund & Borrie 1997). The reality is that handheld information and communication technologies are almost ubiquitous now. Emerging technologies create new opportunities but also new challenges for managers of protected areas, especially wilderness (Martin 2017; Valenzuela 2020).

While GPS has been available through certain devices (e.g., personal locator beacons, recreation-grade GPS units) for decades, the system is now easily accessed through smartphones, which are owned by a majority of U.S. adults (Vogels 2019). Smartphones also grant users access to the internet through an increasingly robust mobile network, and mobile applications (apps) allow smartphone users to focus their devices on specific tasks or activities. Websites and apps often create space for user-generated content (UGC), such as through comment sections, reviews, or media uploads; it is content generated by users instead of publishers or site managers. UGC “disrupts” established communication channels and is “fast becoming the most important and widely used source of travel information” (Salem & Twining-Ward 2018, p. 3). While the use of information has long been considered an appropriate management strategy in the outdoor recreation and protected area management contexts (Roggenbuck & Watson 1985), UGC may undermine traditional approaches to applying this strategy. There are also smartphone-based information sources that are not interactive, such as PDF documents. These are static information sources, like paper books or maps, in that they are not GPS-enabled and they do not facilitate UGC. However, when mobile service is available, they may be updated more readily than paper sources.

The ubiquity of smartphones also extends to long-distance trail corridors. Recent work on the Pacific Crest Trail showed that 97% of long-distance hikers carried smartphones and used them daily (Amerson, Rose, Lepp, & Dustin 2020), and this work has fueled important discourse surrounding the “cognitive costs” of smartphones in wild places (Dustin, Amerson, Rose, & Lepp 2019). Martin (2017) provided a comprehensive overview of the influences of information technology on outdoor recreation and wilderness experiences and management, noting several potential benefits and issues associated with technology. More recently, Valenzuela (2020) argued for researchers to embrace and leverage technology to achieve management objectives. Smartphones and other technologies (e.g., virtual reality and social media platforms) are either already ingrained in society or on the verge of integration such that a paradigm shift among managers is necessary to achieve management goals, and this is especially true for managers of wilderness or natural areas that emphasize primitive experiences (Valenzuela 2020). An understanding of recreationists’ use of smartphones and associated tools can aid managers in responding to them or even leveraging them to achieve management objectives.

Long-distance hiking may represent a valuable activity to explore recreational smartphone use since long-distance hikers rely heavily on external information sources to guide their journeys along the way. Also, when one considers the surge in long-distance hikers and the number of nights spent on trail, the increase in recreational impacts could be significant. This study explored long-distance hikers’ use of information sources with attention to smartphone-based information. One focus was on avenues of communication: how do hikers receive information and from who? The other focus was on what the authors have termed spatial decisions, such as selecting a campsite or deciding where to stop for water, as they have immediate and tangible ramifications for the natural resources. Long-distance trail managers who stay abreast of emerging trends and understand hikers’ use of information sources will have a better understanding of the causes and distribution of recreation impacts, which strengthens their ability to promote low-impact behaviors and sustain the natural resources for future generations. Understanding long-distance hikers’ smartphone use and spatial decisions may also inform future research on long-distance trails, recreational smartphone use, or spatial decisions.

Long-distance hiking may represent a valuable activity to explore recreational smartphone use since long-distance hikers rely heavily on external information sources to guide their journeys along the way. Also, when one considers the surge in long-distance hikers and the number of nights spent on trail, the increase in recreational impacts could be significant. This study explored long-distance hikers’ use of information sources with attention to smartphone-based information. One focus was on avenues of communication: how do hikers receive information and from who? The other focus was on what the authors have termed spatial decisions, such as selecting a campsite or deciding where to stop for water, as they have immediate and tangible ramifications for the natural resources. Long-distance trail managers who stay abreast of emerging trends and understand hikers’ use of information sources will have a better understanding of the causes and distribution of recreation impacts, which strengthens their ability to promote low-impact behaviors and sustain the natural resources for future generations. Understanding long-distance hikers’ smartphone use and spatial decisions may also inform future research on long-distance trails, recreational smartphone use, or spatial decisions.

Methods

On-site semi-structured interviews were employed to generate data related to decision-making and the use of information sources by long-distance hikers. This method was chosen for its ability to focus on pre-determined topics while avoiding a fixed set of responses (Given 2008). Open-ended questions and probing questions allow researchers to explore phenomena with participants and uncover new insights. The first author acted as a participant-researcher to facilitate interviews in a “natural” setting (Lincoln & Guba 1985). Conducting interviews on-site as a participant-researcher allowed for quick rapport between the researcher and the other participants, minimized issues of recall, and allowed the phenomena to be discussed in their context.

The semi-structured interview protocol followed an extensive review of literature and was developed to capture hiker characteristics and demographics (e.g., how many miles have you come so far, how experienced would you describe yourself as a backpacker before this hike), information use (e.g., what information sources are you using, how do you use each source, how does GPS impact your hiking experience ), and spatial decisions while on trail (e.g., how do you decide where to camp, how do you decide where to stop for water). The interviews were conducted with hikers encountered on the AT in New Hampshire, USA in the last week of July and the first week of August 2019, which allowed for interaction with northbound and southbound thru-hikers as well as with section hikers.

Out of the twenty-three hikers contacted and informed of the project, one individual rejected the offer to participate citing a lack of desire to participate, and two individuals rejected due to time constraints. In total, seventeen interviews were conducted with twenty long-distance hikers participating. Interviews ranged from 26 to 121 minutes, averaging 57 minutes. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim on a smartphone. Transcripts were analyzed and coded following Tracy’s (2013) guidance on iterative analysis while keeping in mind the goal of understanding long-distance hiker avenues of communication and spatial decision-making on long-distance trails. Primary- and second-cycle coding led to the identification and description of salient themes, which are summarized and represented through key invivo quotes. Trustworthiness of themes was checked through a process like Birt et al.’s (2016) synthesized member-checking process. A list of preliminary themes was sent to thirteen participants who provided email addresses, and nine responded with comments. Most feedback was affirmative, but some wording was adjusted according to member-check input to reflect the range of responses more accurately.

Results

Description of the Participants

Participants ranged in age from 22 to 56 years old. Participants had been on-trail between 28 and 150 days and had hiked between 295 to 1,880 miles (475 to 3,025 km) at the time of the interview. Hikers traveling northbound (n=14) and southbound (n=6) were interviewed. While most were attempting thru-hikes (n=17), three participants were undertaking section hikes. Four of the thru-hikers were flip-flopping the trail, a practice where the entire trail is hiked in non-consecutive segments within one year.

One participant was on the final leg of a three-year section hike of the AT, one participant had never backpacked overnight before this journey, and the rest had backpacked between two and ten days. Two participants had formal experience leading backpacking trips but considered themselves inexperienced before this trip. As one explained, “I knew like textbook the way you’re supposed to do things. But that’s a lot different when you’re on a thru-hike.” When asked to describe their level of experience at the time of the interview, participants offered a range of responses from expert to novice. However, the majority indicated they were experienced but still learning.

Avenues of Communication

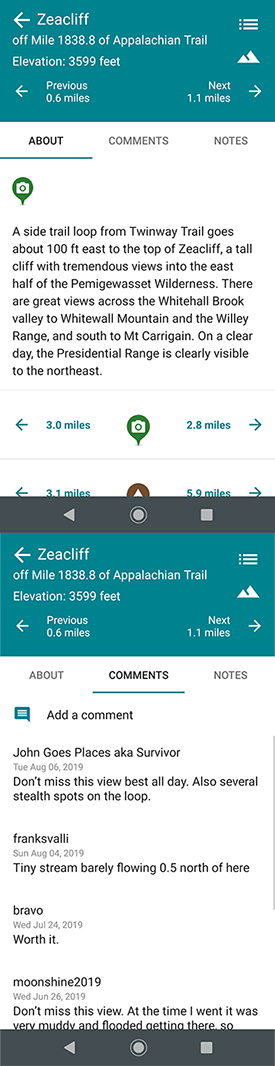

All participants carried a smartphone with them, and all used at least one of three AT-specific guides: The A.T. Guide (better known as “AWOL’s guide,” theatguide.com), Guthook’s Guide to the A.T. (an offline smartphone application known as “Guthook,” https://atlasguides.com/appalachian-trail/ ), and the Appalachian Trail Thru-Hikers Companion (the “official guide” according to the ATC, https://aldha.org/companion)(Figure 2a-b). A PDF version of AWOL’s guide was used by six participants. As mentioned earlier, although PDFs are smartphone-based, they are static sources of information in that they are not GPS-enabled and they do not facilitate user-generated content. While thirteen participants used Guthook, twelve of them also had a supplementary static source of information. Only one participant used Guthook alone. All participants used their phones for taking photos (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Thru-hiker taking photo with smartphone from Zeacliff Overlook, Pemigewasset Wilderness, Appalachian Trail, New Hampshire, USA.

GPS

Many participants valued their smartphones’ ability to verify their location and help them stay on trail. The majority of GPS use was through the Guthook application, but hikers also used Google maps and other apps to check their location.

“Guthooks is also, like kind of gratifying. Like you can… hit your location and see how close you are like exactly on-trail.” (7)

But many hikers also mentioned reservations about GPS effect on the experience.

“Sometimes it makes it just seem like you’re trying to get something over with.” (6)

Of the seven hikers who carried only static sources, four reported accessing GPS through other means.

“There is an application called iHealth, and you can see how many miles you hike during the day.” (8)

“I use Google quite a bit, Google Maps all the time, to try and– sometimes I’m like, ‘am I on the trail?’ Haven’t seen any blazes in a while. Sometimes I’ll be able to pull it up, and like it has little green dashes” (12)

Only three participants, each of whom carried paper guides, did not use GPS for navigating on the trail, although one of them did carry a personal locator beacon.

User-Generated Content

Mobile application users had overwhelmingly positive statements regarding the user-generated content, which they referred to as “comments.”

“Guthooks is nice. You can find like little secret gems along the trail… because of a random Guthook comment that somebody finds” (2)

“Seeing some people’s comments lets you know that you should really make the trip off-trail to go see this vista or campsite or whatever it is. I think that the comments enhance my experience by sharing other people’s experiences and letting me know if it’s something worthwhile or something that I want to skip.” (3)

Although participants pointed out that the comments were not entirely reliable, the solution seemed to be more comments.

“You can’t take just one comment, because those are just people like you or I just commenting, sometimes in a bad mood. I try to read a few of the comments and get the gist.” (9)

“The more they’re completely crowdsourcing everything, and the more people that use it, eventually, you get a critical mass and the cream would rise to the top.” (13)

Hikers who did not download Guthook still reported benefitting from the comments.

“Although we don’t have Guthook, we definitely have the advantage of information from Guthook through other hikers. That’s been nice on occasion.” (17)

Communication with Managers

The ATC encourages thru-hikers to register their hikes “so they can plan their itinerary in order to avoid the social and ecological impacts of overcrowding” (ATC 2019b). Fifteen participants (all but two of the thru-hikers) registered, citing desires to help the ATC, to be recognized and documented, or to receive a hang tag (a commemorative tag with Leave No Trace information designed to hang on a pack).

“I thought it was the proper thing to do. And also it could help keep track of people coming in and out. And also I would like to have my name on the database so that you know that I hiked the AT! ” (1)

“I just thought it’d be fun to register. Get a tag. That was maybe the main thing. I wanted a tag.” (19)

However, these motivations did not resonate to the same extent with section hikers or the thru-hikers who did not start at one of the ATC’s Visitor Centers.

“Since I’m only out here for like a month, just doing two states, pretty much, I was like, ‘Ah, it’s not a big deal. They don’t need to know I’m out here.’ And it’d be weird having the badge and people would ask me about it, and I’d be like, ‘Oh well I’m just section hiking.’” (10)

Many of those who registered were set on a particular date, but some thru-hikers decided to shift their start date after visiting the ATC website. They also benefitted from the education provided at the visitor center at the southern terminus.

“I did look on the site… I was going to start on [a particular day but] it was super full. I backed it up a day and went [the day before].” (19)

“They give you some tips, and they show you how to hang your bear bag as well, and they ask you to be really careful with your trash and with your food.” (8)

Spatial Decisions

Acknowledging that trails intend to concentrate recreation impacts to a narrow linear corridor, the semi-structured interview protocol sought to elucidate participants’ decisions to step off the trail and the role that their information sources play in those decisions. Camping, visiting points of interest, and stopping for water appeared to be strongly influenced by information sources while the other spatial decisions examined (where to break and where to dispose of human waste) were less clearly linked to trail guide information, user-generated or otherwise.

Camping

Although campsite distribution strategies have been described in the literature (Marion, Arredondo, Wimpey, & Meadema 2018), participants tended to simply view campsites as either “official” or “stealth.” Official sites are those published in guidebooks. Stealth sites are not formally mentioned in guidebooks, although they may be noted by other hikers via mobile app comment feature (Figure 4). Guthook comments were valuable for some hikers to locate “stealth” sites that aligned with their preferred distance for the day. However, participants who used only static sources still knew where to look for existing stealth sites.

Figure 4 – Heavily trampled unofficial camping area where the AT crosses Mink Brook, White Mountain National Forest, New Hampshire, USA. A mobile app had an entry for the stream, and many user-generated comments mentioned camping (e.g., “Great place for lunch or camping” and “Tent island, fit 7 tents on the island by the fire ring. Great spot.”).

“A lot of the Guthook– it’s mostly official campsites. But with comments, a lot of hikers can tell you where to go, how far, and then give you more information about it.” (1)

“I’ll only look for a stealth site if there isn’t a campsite or a shelter within the miles, plus or minus a couple of miles of what I plan on doing. Then I’ll start clicking on other icons in the Guthook’s app where I do want to stay and see if anyone is mentioning a stealth site.” (13)

“It’s a good guess, when there’s a stream or whatever, there’s usually a stealth site somewhere close by within 0.2.” (20)

Only one participant reported true dispersed campsite selection.

“When… it’s really late, and I haven’t found a spot, sometimes I just start wandering in the woods to find a spot. Cause you’re like, ‘Something’s gonna be flat somewhere around here.’… I don’t think anyone will ever find some of those spots that I do.” (12)

Points of Interest

Participants wanted to enrich their hikes by exploring points of interest, but they were also conscientious of doing “sideways miles.” Word of mouth, Guthook comments, and distance often determined if a hiker chose to go to a point of interest or not (Figure 5).

“It’s usually about word of mouth that I’m like ‘I’m going to go through a blue blaze.’ Not much else takes me off.” (2)

“Is it worth going up there? Well, the last comment was that the trees have grown up. ‘You can’t see anything.’ Well, I’m not going there. Thanks to Guthooks, I was able to learn not to waste an hour going half a mile out of the way.” (9)

“Something that’s not too far off the path– a lake or a pond that I might go swimming in or an exceptional view that everyone is raving about… Unless it’s one of those two things, I’m not really getting off the trail. I try not to do too many sideways miles.” (13)

Water

Some participants closely managed water stops based on the quality and reliability of sources, while others simply tried to carry as little as possible. Comments provided enough information that Guthook users could be very selective except in the driest times. Hikers who carried only static information sources used word of mouth to learn about unreliable sources, but sometimes they ended up with suboptimal water.

Figure 5 – Some points of interest, like the summit of Mount Lafayette in White Mountain National Forest and adjacent to the Pemigewasset Wilderness, New Hampshire, USA, are more popular than others.

“There was a really bad water source that we had a couple days ago, and we were just like ‘Nah, like let’s push on to get a little bit better water,’… I don’t really prefer to dig it out of a bog.” (5)

“I try to stop where there is a good spring, but sometimes, yeah you don’t really have the choice, so yeah. Many times I had to stop and like use some frog water.” (8)

“We’ll try and look for something three to five miles from where we’re at… And then using Guthook’s too just to figure out what are good water sources. If it’s like three miles out and it says ‘This water’s shitty,’ and there’s another one five miles out, we’ll go to the five mile one.” (15)

“I ask other hikers a lot. Like now especially with water sources, especially as it gets later into the season, like the sources AWOL is listing as unreliable, asking other hikers ‘Hey, did you see water here?” (18)

Discussion and Implications

This inquiry further substantiates a phenomenon recently documented by Amerson et al. (2020)—smartphones are part of the long-distance hiking world. In this small sample, all hikers carried smartphones, but they engaged with them to different degrees. The mobile app essentially adds GPS and user-generated content to the same base information as the static guides. For hikers with access to GPS, the primary use was simply to confirm one’s location. While increasing use of GPS in backcountry or protected natural areas certainly warrants investigation into potential experiential and biophysical impacts (Martin & Blackwell 2016), it appears that GPS did not guide spatial decision-making for the participants in this research. As GPS has become more accessible and mobile networks become more robust, future research should explore the impacts of this connectedness on the wilderness experience.

On the other hand, user-generated content does appear to influence spatial decision-making, at least for some decisions. Even those hikers who made a point to “disconnect” reported that they received crowd-sourced information via word of mouth. User-generated content allowed hikers to plan around stealth sites with certainty and told hikers which points of interest and springs to visit and which to hike past. While water sources are critical to survival on the trail, the motivations that underpin visiting points of interest are less clear. While these stops could be entirely hedonistic, a better understanding of what motivates hikers to stop or venture off-trail could be valuable information for managers seeking to steer use or for researchers seeking to understand leisure behavior. Future research should also account for the reality that accessing technology can be convoluted. Participants who initially indicated that they do not use GPS, following probing questions, revealed that they did access GPS but through less apparent means, such as a smart watch or health app. Similarly, participants without Guthook revealed through discussion that they still received information from Guthook comments via word of mouth. Thus, research instruments that attempt to capture technology use among recreationists must consider alternative means of using technology or accessing information and communication networks.

Given that resource impacts are inextricably linked to recreationists’ physical presence, an information source that determines the spatial distribution of hikers must, to some extent, determine the spatial distribution of impacts (Cole 2009). This is true for any trail guide, but the UGC of mobile apps sets them apart from more traditional guides. The lack of land manager input, the ease of contributing content, and the complacence with which some users post increases the likelihood that sensitive or problematic information could be shared. For example, a well-intentioned comment may indicate the existence of a campsite that managers have attempted to inconspicuously close. While the speed with which UGC is shared has some benefits for recreationists (e.g., up-to-date information on water sources), it could also be problematic. For example, app users who share the location of trail magic (well-intentioned offerings of food or other displays of care for hikers) could contribute to crowding at those locations. Thus, managers should be aware of the influence of UGC on protected area visitors and respond where necessary. For example, managers should check “stealth” sites indicated by UGC for proximity to sensitive resources and potential for expansion. When better sites exist nearby, managers could close the site and request that the comments be removed, and the appropriate site indicated in the app. In longer stretches of trail without sustainable campsite options, UGC could aid managers in identifying where new campsites should be located to minimize unconfined camping and concentrate resource impacts (Marion et al. 2018). Researchers could use content analysis of comments or leverage geographic information systems to better understand the establishment of stealth sites or to inform where managers should designate new sites or close redundant ones.

If managers intend to guide long-distance hikers toward preferred behaviors, they must work proactively with app developers and users. Based on conversations about registering their hikes, participants in this research appeared willing to follow the guidance of trail managers to minimize their impacts, such as hanging their food to protect wildlife or shifting their start dates to minimize crowding. The ATC’s web-based registration system paired with education sessions at the southern terminus helped many hikers make “good” decisions. More interventions acknowledging the prevalence of user-generated content should be developed as the scene continues to unfold, and researchers should evaluate the efficacy of these interventions and connect their findings to similar research (e.g., Hockett, Marion, & Leung 2017; Marion & Reid 2007) to aid in a greater collective understanding of recreation behavior and low impact ethics.

If managers intend to foster specific behaviors, norm activation (Heberlein 2012; Schwartz 1977) may offer valuable guidance. Since AT hikers “are relatively well-informed about a variety of minimum impact skills” (Newman, Manning, Bacon, Graefe, & Gerard 2003, p. 37), and since thru-hiker culture prioritizes pro-environmental behaviors (at least in face value) (Redpath 2016; Siudzinksi 2007), activating this norm to promote recently developed minimum impact practices could yield positive behavior change, as it has with distributing thru-hike starts at the southern terminus. Researchers should continue to evaluate the effectiveness of impact-reducing communications as information and communication technologies further permeate the outdoor recreation realm. Technology-related recommendations should be actively associated with other low-impact practices education and communication efforts, which have begun to reflect the prevalence of mobile devices (e.g., wear headphones to listen to music (Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics 2020)). Similar guidelines could be developed to guide long-distance hikers’ use of information in the digital age. Hikers could be encouraged to use only “official” campsites. App users could be discouraged from posting new camping locations. Manager validation or approval of sustainable campsites could be added to apps to clarify for hikers which sites are appropriate for use. Marion et al. (2018) suggested that GPS could be used to help connect recreationists to appropriate sites, but UGC in GPS-enabled apps helped participants in this research to find and plan their days around inappropriate “stealth” sites. Given the potential impacts associated with camping, future research should help to clarify the “official” versus “stealth” site dichotomy that was prevalent among the participants in this research and increase the likelihood that recreationists choose appropriate sites for overnight use.

While not reported here, each participant in this research discussed the appropriateness of technology on the trail in depth. Some embraced technology fully while others tried to minimize its intrusion into their hikes, but many fell in the middle. They relied on their phones and viewed them as valuable tools, but they also echoed the sentiments articulated by Dustin et al. (2019) that information and communication technologies detract from the trail experience. Despite these concerns, participants found smartphones too convenient and too practical to leave at home. For the participants who were on the two ends of the spectrum, neither group appears likely to be swayed, but both respect the other group’s point of view. All the participants shared many key characteristics. They chose to take long walks in nature. They respect other hikers’ autonomy, and they want the freedom to choose their own style of adventure. Mirroring Dustin, Beck, and Rose’s (2018) charge, managers and planners must find the underlying wilderness values of various user groups and develop palatable policies on the common ground.

While it is a matter of opinion whether these types of technology are inherently incompatible with the wilderness experience, it is clear that connectivity is increasing, and recreationists (including long-distance hikers) are using information and communication technologies to inform their pursuits.

The shift that is occurring boils down to this: previously, people had to actively choose to bring information and communication technologies on the trail. They were clunky, unreliable, and often inconvenient. Now, paper guidebooks are beginning to be considered clunky, unreliable, and often inconvenient. Hikers must now be proactive if they want to avoid information and communication technologies on the trail. While it is a matter of opinion whether these types of technology are inherently incompatible with the wilderness experience, it is clear that connectivity is increasing, and recreationists (including long-distance hikers) are using information and communication technologies to inform their pursuits. Managers and researchers must evaluate the experiential and biophysical impacts of these emerging technologies. While a recent research agenda-setting document asserts that information and communication technologies are here to stay (Valenzuela 2020), wilderness managers are still charged with providing “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation” (Wilderness Act, 1964). It is our hope that a better understanding of recreationists’ use of smartphones can help managers and researchers as wildland recreation moves into the digital age.

Limitations

This research is based on data generated by a participant-researcher and a small sample of Appalachian Trail long-distance hikers in a natural setting. While the participant-researcher carried a variety of information sources (maps, a paper databook, smartphone-based guide), the use of the smartphone to record the interviews may have influenced the participants’ perceptions of the researcher’s views and their responses. Although the interview protocol attempted to use neutral language and the semi-structured nature of the interview attempts to allow a broad range of responses, the questions asked still limit the range of possible responses to some extent. While member-checking helps to increase trustworthiness, coding and synthesizing of data were interpretive processes performed exclusively by the first author. Interpretation of the results was shared by the two authors, but other peers (both long-distance hikers and researchers unassociated with this project) aided in the development of these ideas.

While the results reported here reflect the experiences of these participants, more extensive sampling is needed to generalize beyond this group. Continuing this line of research with more hikers, with different levels of experience and at different portions of the AT or on other trails, would likely yield new findings and a better understanding of smartphone use in the outdoor recreation realm.

Acknowledgements

The utmost gratitude is owed to the participants of this research. We greatly appreciate Dr. KangJae “Jerry” Lee, Dr. Erin Seekamp, and two anonymous reviewers for providing constructive comments. We would also like to thank NC State University Department of Parks, Recreation & Tourism Management and Recreation Resources Service for their support of this project.

About the Authors

ANDREW ROGERS recently received his M.S. in Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management from the College of Natural Resources at North Carolina State University. Andrew’s research interests fall in the realms of visitor use management and recreation ecology, and they are inspired by his personal endeavors and interactions with recreationists; email: arogers@ncsu.edu

DR. YU-FAI LEUNG is a professor in the Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management, College of Natural Resources at North Carolina State University (USA). Yu-Fai’s research aims to advance the science and practice of sustainable visitor management in parks, protected and wilderness areas globally; email: leung@ncsu.edu

References

Amerson, K., J. Rose, A. Lepp, & D. Dustin. 2020. Time on the trail, smartphone use, and place attachment among Pacific Crest Trail thru-hikers. Journal of Leisure Research 51(3): 308-324.

Appalachian Trail Conservancy 2019a. 2000 milers. Retrieved from http://www.appalachiantrail.org/home/community/2000-milers. Last visited January 30, 2020.

Appalachian Trail Conservancy 2019b. Thru-hiker registration. Retrieved from http://appalachiantrail.org/home/explore-the-trail/thru-hiking/voluntary-thru-hiker-registration. Last visited January 30, 2020.

Birt, L., S. Scott, D. Cavers, C. Campbell, & F. Walter. 2016. Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research 26(13): 1802-1811.

Cole, D. N. 2009. Ecological impacts of wilderness recreation and their management. In C. P. Dawson & J. C. Hendee (Eds.), Wilderness management: Stewardship and protection of resources and values (4th ed., pp. 395-438). Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Cole, D. N., & C. A. Monz. 2004. Spatial patterns of recreation impact on experimental campsites. Journal of Environmental Management 70: 73-84.

Daniels, M. L., & J. L. Marion. 2006. Visitor evaluations of management actions at a highly impacted Appalachian Trail camping area. Environmental Management 38(6): 1006-1019.

Dustin, D., K. Amerson, J. Rose, & A. Lepp. 2019. The cognitive costs of distracted hiking. International Journal of Wilderness 25(3): 12-21.

Dustin, D., L. Beck, & J. Rose. 2018. Interpreting the wilderness act: A question for fidelity. International Journal of Wilderness 24(1): 58-67.

Fondren, K. M., & R. Brinkman. 2019. A comparison of hiking communities on the Appalachian and Pacific Crest Trails. Advance online publication. Leisure Sciences DOI: 10.1080/01490400.2019.1597789.

Freimund, W., & B. Borrie. 1997. Wilderness @ internet: Wilderness in the 21st century—Are there technical solutions to our technical problems? International Journal of Wilderness 3(4): 21-23.

Given, L. M. 2008. The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (Vols. 1-0). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. DOI: 10.4135/9781412963909

Hammitt, W. E., D. N. Cole, & C. A. Monz. Eds. 2015. Wildland recreation: Ecology and management (3rd edition). Wiley Blackwell.

Heberlein, T. A. 2012. Navigating environmental attitudes. New York, NY: Oxford.

Hockett, K. S., J. L. Marion, and Y.F. Leung. 2017. The efficacy of combined educational and site management actions in reducing off-trail hiking in an urban-proximate protected area. Journal of Environmental Management 203: 17-28.

Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics 2020. Principle 7: Be considerate of other visitors. Retrieved from https://lnt.org/why/7-principles/be-considerate-of-other-visitors/. Last visited January 30, 2020.

Lincoln, Y. S., & E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Manning, R. E., N. L. Ballinger, J. Marion, & J. Roggenbuck. 1996. Recreation management in natural areas: Problems and practices, status and trends. Natural Areas Journal 16(2): 142-146.

Marion, J., J. Arredondo, J. Wimpey, & F. Meadema. 2018. Applying recreation ecology science to sustainably manage camping impacts: A classification of camping management strategies. International Journal of Wilderness 14(2): 84-100.

Marion, J. L., & S. E. Reid. 2007. Minimising visitor impacts to protected areas: The efficacy of low impact education programmes. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 15(1): 5-27.

Martin, S. 2017. Real and potential influences of information technology on outdoor recreation and wilderness experiences and management. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 35(1): 98-101.

Martin, S. R., & J. L. Blackwell. 2016. Personal locator beacons: Influences on wilderness visitor behavior. International Journal of Wilderness 22(1): 25-31.

National Park Service. 2014. Foundation document: Appalachian National Scenic Trail. https://www.nps.gov/appa/getinvolved/upload/APPA_Foundation-Document_December_2014.pdf

Newman, P., R. Manning, J. Bacon, A. Graefe, & K. Gerard. 2003. An evaluation of Appalachian Trail hikers’ knowledge of minimum impact skills and practices. International Journal of Wilderness 9(2): 34-38.

Outdoor Foundation 2018. Outdoor participation report 2018. Retrieved from https://outdoorindustry.org/resource/2018-outdoor-participation-report/. Last visited January 30, 2020.

Redpath, A. 2016. For the love of long walks: Impact of long-distance trail thru-hikes in the United States on environmental attitudes in relation to sustainability. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Roggenbuck, J. W., & A. E. Watson. 1985. Providing information for management purposes. In Kulhavy, D. L. and Conner, R. N. (Eds.), Wilderness and Natural Areas in the Eastern United States: A Management Challenge (pp. 236-242). Nacogdoches, TX: Stephen F. Austin State University, School of Forestry.

Salem, T. M., & L. D. Twining-Ward. 2018. The voice of travelers: Leveraging user-generated content for tourism development. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/656581537536830430/The-Voice-of-Travelers-Leveraging-User-Generated-Content-for-Tourism-Development-2018. Last visited February 17, 2020.

Schwartz, S. H. 1977) Normative influences on altruism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 10: 221-279.

Siudzinski, R. A. 2007. Not all who wander are lost: An ethnographic study of individual knowledge construction within a community of practice (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Blacksburg, VA: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Tracy, S. J. 2013. Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Valenzuela, F. 2020. Technology and outdoor recreation in the dawning of the age of constant and instant digital connectivity. In S. Selin, L. K. Cerveny, D. J. Blahna, & A. B. Miller (Eds.), Igniting research for outdoor recreation: Linking science, policy, and action (pp. 101–113). Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-987. Portland, OR: USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station.

Vogels, E. A. 2019, September 9. Millennials stand out for their technology use, but older generations also embrace digital life. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/09/09/us-generations-technology-use/

Wilderness Act, 16 U.S.C. § 1131 (1964).

Read Next

Foundation and Future of Long Distance Trails

We begin this special edition of the International Journal of Wilderness with references to the U.S. Wilderness and National Trails System Acts to illustrate the significance and interconnectedness of wilderness areas and long-distance trails.

With Collaboration We Can Overcome Challenges Together

The concepts of “shared stewardship” or “collaborative management” can be challenging. They require shared vision, definition of clear roles and responsibilities, and commitment to the collaborative process.

Shared Stewardship and National Scenic Trails: Building on a Legacy of Partnerships

National Scenic Trails connect people with the natural and cultural heritage of the United States. Theses trails also provide important opportunities for agencies to engage partners in trail stewardship and sponsorship.