Haze shrouds the Oquirrh Mountains and the Salt Lake Valley, which borders popular urban-proximate wilderness and nonwilderness areas. photo credit © Chris Zajchowski

Second Class Wilderness: Separate but Unequal Air Resources in American Wilderness

Stewardship

December 2019 | Volume 25, Number 3

The United States has a long history throughout which equitable access to resources has been denied to segments of the population along racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic distinctions through informal, legal, and sometimes violent means. For instance, in 1954, the landmark US Supreme Court case, Brown vs. Board of Education, ended 58 years of federally supported racial segregation within our nation’s public school system based on the “separate but equal” doctrine. The arc of American park and protected area management has followed a similar pattern. The first US parks and protected areas established late in the 19th and early in the 20th century were accessible largely to affluent, white, and predominantly male visitors. Barriers to access existed for those lacking economic means, adequate leisure time, and those of minority racial and ethnic status. Perhaps most egregious were the legal restrictions on American Indians, many of whom were legally prohibited during the latter half of the 19th century from leaving reservations and utilizing parks and protected areas established on lands from which they were forcibly removed (Keller and Turek 1998; Marks 1999; Prucha 2000; Spence 1996).

As the automobile provided greater mobility across socioeconomic status, parks diversified, leading to greater mixing across groups (Young 2009). However, barriers to equitable outdoor recreation resources remained. In the 1930s, managers in the emerging Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountain National Parks deferred to the regulations and laws of the southern states of Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee by developing “separate but equal facilities” at picnic areas and campgrounds, which effectively barred African American visitors from most park amenities (Young 2009, p. 652). Moreover, while National Park Service (NPS) Director Newton Drury ordered the end of segregation in the NPS in 1942, 21st-century scholars have continued to argue that the wilderness ethos developed and imbued in many federal land management agency policies continues to reflect and reinforce white and affluent stakeholders’ values and interests (e.g., Davis 2019; Smith 2005; Weber and Sultana 2013).

In this article, we explore how the US legal landscape governing air resource management leads to a similar separate and unequal provision of wilderness opportunities for a diverse American public. Specifically, while we recognize the many benefits of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 for air resources nationwide, here we review the adverse implications of the creation of Class I and Class II wilderness areas for visitors and wilderness-proximate communities. We acknowledge that drawing a parallel between wilderness management and the “separate but equal” legal doctrine may raise eyebrows, as the latter is certainly a more explicit and egregious injustice forced upon minority groups, specifically communities of color. Yet, with air pollution considered one of the greatest environmental health risks worldwide (e.g., Ebenstein, Fan, Greenstone, He, and Zhou 2017; Tessum et al. 2019), we believe it is appropriate for our field to discuss how the tiered protections of air resources may expose visitors, unbeknownst to them, to increased health risks (i.e., cardiac, reproductive, respiratory) and unequal visitor experiences (e.g., Zajchowski, Brownlee, and Rose 2018). Using the example of the urban-proximate wilderness areas of Utah’s Wasatch Front – Lone Peak, Mount Olympus, Timpanogos, and Twin Peaks Wilderness Areas – we suggest that these health risks related to air pollution may be disproportionately borne by wilderness visitors from nearby urban areas, many of whom bear a similar burden of air pollution at home (e.g., Collins and Grineski 2019; Zajchowski and Rose 2018). Furthermore, we suggest that these urban-proximate wilderness visitors may be more diverse than visitors to more remote, Class I wilderness areas, begging the question of whether equitable access to air resources across wilderness designations is prevented as a result of current air resource policy. In closing, we present research and policy-relevant suggestions to explore the provision of equal air quality protections across all wilderness areas in the United States.

Air Resource Classification

Legal protections for wilderness areas have historically been a contentious subject. From the signing of the US National Wilderness Preservation Act of 1964 onward (16 U.S.C. 1131-1136, 78 Stat. 890), defining and managing for “untrammeled” and “primeval” wilderness experiences has involved constant review, negotiation, litigation, and legislation (e.g., Dustin, Beck, and Rose 2018; Mace, Bell, and Loomis 2004). With regards to air quality, guiding directives for air resource management in wilderness areas has evolved from the Air Quality Act of 1967 through multiple amendments to the Clean Air Act (1970, 1977, 1990) and the implementation of the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Regional Haze Program (EPA 2019c).

Perhaps the most substantial air resource protections for wilderness areas are codified in the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 (Zajchowski, Lackey, and McNay 2019). This act established three tiers of air quality control across lands managed by federal agencies, specifically the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), Forest Service (USFS), and National Park Service (NPS). That said, the amendments primarily focused on wilderness areas and national parks. Class I areas were given the most stringent protections, available under 42 U.S.C. 7473. All areas designated as wilderness larger than 5,000 acres (2023 ha) and national parks larger than 6,000 acres (2,428 ha) that existed prior to 1977 were automatically given Class I protections (NPS 2019) due to their “natural, scenic, recreational, or historic” worth (EPA 2019b). These protections were designed to prevent significant deterioration (PSD) of existing clean air resources through limitations on nearby stationary sources (e.g., power plants) using the best available control technology (BACT)(Branagan 1977). Any wilderness areas designated after August 7, 1977, were given a Class II designation, allowing for controlled growth. Class III designations were reserved for areas of high industrial output that would be severely impacted by restrictions on air quality (Adams et al. 1991). There are currently no Class III areas in the United States.

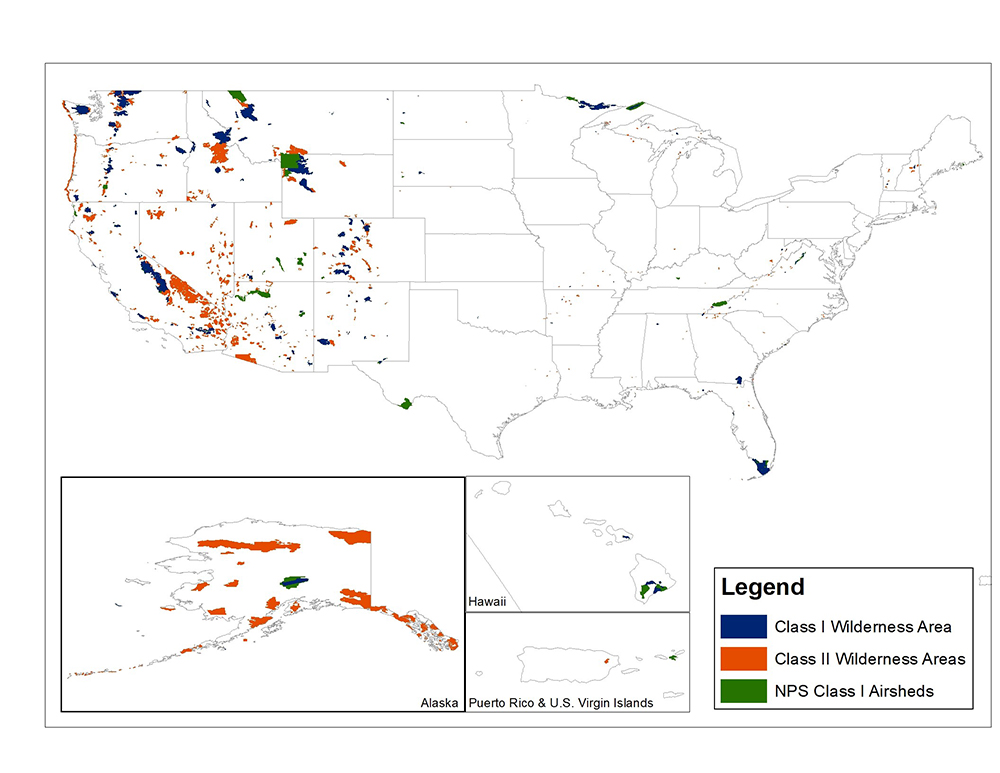

As of 2019, 803 wilderness areas, comprising more that 111 million acres (44,920,106 ha) of US federal land, represent the National Wilderness Preservation System (Wilderness Connect 2019). Of these, 108 designated wilderness areas and 48 national parks have a Class I designation (EPA 2019a). These 108 areas comprise 14% of all designated wilderness areas, meaning that the vast majority of all US wilderness areas (86%) are designated as Class II (Figure 1). On the surface, this distinction would seem primarily semantic; however, the implications for monitoring and management of air quality between different classifications is striking.

Federal Land Managers (FLMs) assigned to Class I wilderness areas are responsible for protecting Air Quality Related Values (AQRVs), such as vegetation, soils, water, fish, wildlife, and visibility, within the lands in their purview (NPS 2002). FLMs establish criteria to determine impacts to AQVRs and can ultimately recommend that permitting agencies deny permits to new stationary sources of air pollution or modifications to exiting sources due to forecasted impacts (EPA 2019a). Analysis occurs regularly to determine the impacts on AQRVs within Class I wilderness areas. Any facility located within 50 kilometers (31 miles) of a Class I area will be required to submit to analysis of emissions; outside 50 kilometers, an emissions-to-distance ratio based on proximity to the Class I area determines whether an analysis is required (Missouri Department of Natural Resources 2013). In addition to more localized reductions of air pollution, the EPA has attempted to limit the effect of interstate pollution by requiring states to address facilities that contribute to air pollution in other states (Malm 2016). The Clean Air Interstate Rule uses a “cap and trade” system to reduce target emissions that impact adjacent states’ air quality standards. Any state or tribal organization that manages a Class I area may invoke interstate dispute resolution under the EPA to protect the air quality of that Class I area (EPA 2013). In sum, Class I areas enjoy the protections from the EPA under the PSD permit program, where permit applicants must prove that the proposed construction or modification of an emissions source will not cause or contribute to the degradation of air quality (EPA 2013).

The remaining three-quarters of wilderness area acreage in the United States is classified as Class II. As Branagan (1977) describes, this second tier of air quality control allows for “reasonable” growth where decisions regarding land use are not dictated primarily by air quality concerns. In other words, the air resources of Class II wilderness areas may be influenced by the social or economic priorities of neighboring communities or those decided at the state level. PSD and AQRV-related legal mandates for analysis and review are lacking for these Class II areas, which, in turn, provides a disincentive for other parties, such as states, to curb the impacts of new or existing sources of air degradation on wilderness air resources. In turn, this Class II status often leaves managers without the proper legal mandates to address degradation of wilderness resources (Zajchowski et al. 2019). In a recent policy analysis of the impact of federal air quality policy on the work of US park and protected area professionals, one participant commented:

When we would try to fight the big fight against the State for a particular thing, we were always shot down because we weren’t a Class I park or a Class I preserve. So, if you fall under the protection that the CAA gives you or that we get by being Class I park—that’s great—it makes my job easy because the law gives me that ability to engage. If I’m in a location that has no air quality station, and I’m using data from far away or I’m relying on the [permit] applicant to provide the data, or I’m begging and borrowing for information that they are never going to give me. It’s a world of difference (Zajchowski, Lackey, and McNay 2019, p. 1013).

This sentiment was shared by other park professionals, who illuminated that the Class II designation did not allow them to manage wilderness areas and protect wilderness resources in an equivalent manner as Class I areas.

The State of Air

Under the provisions of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977, states are able to change the designation of Class II areas to Class I (Adams et al. 1991). That said, as states balance many legal and social mandates, they regularly default to standards codified with the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS; EPA 2019a). The NAAQS dictate national thresholds for criteria pollutants – carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, particle pollution, sulfur dioxide – that can affect public health and welfare. When specific pollutants regularly exceed these thresholds (e.g., 70 ppb ozone), states are required to create a State Implementation Plan (EPA 2019a), in which they outline how they plan to improve ambient air pollutants to regain compliance with the NAAQS. Importantly, these standards allow for higher thresholds for pollutants than in Class I wilderness areas. In other words, while wilderness managers attempt to retain or achieve “pristine” conditions far below the NAAQS, states without Class I areas can allow for pollutant dispersion up to the NAAQS thresholds (Branagan 1977). And, some states, such as Utah, are in nonattainment with NAAQS surrounding specific criteria pollutants (i.e., ozone [UDEQ 2018], particulate matter [UDEQ 2019]), which creates cascading effects for air resources in their Class II wilderness areas.

The example of Utah helps to further illustrate the results of the bifurcation of wilderness designations into Class I and Class II. Many exceedances of the NAAQS within Utah occur at the doorsteps of designated Class II wilderness areas (Figure 2). Each of the four wilderness areas managed by the USFS – Lone Peak, Mount Olympus, Timpanogos, and Twin Peaks – sit adjacent to Utah’s main population center, the Wasatch Front. As a result, the emissions from cars, homes, businesses, and factories all contribute to local air pollution challenges and degrade air quality near and within urban-proximate wilderness areas. As Horel and colleagues (2016) observed, ozone values can exceed the NAAQS proximal to Twin Peaks and Lone Peak Wilderness Areas of the Wasatch Front. Additionally, particulate matter deposition from anthropogenic emissions has been documented in the snowpack in the Wasatch Mountains (Hall, Maurer, Hoch, Taylor, and Bowling 2014), making it logical to infer similar impacts from particulate matter in Wasatch wilderness areas. So, while impacts to AQRVs are present (e.g., vegetation [Wager and Baker 2006], visibility [Zajchowski et al. 2019]), the Class II status for each of these wilderness areas prevents the same level of monitoring, modeling, and management that is afforded to their Class I peers.

Interestingly, these Class II areas of the Wasatch Front were established between 1978 and 1984. The timing of the designation of these areas, after the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977, forced them to join the National Wilderness Preservation System without the air resource protections afforded to Class I areas in southern Utah (e.g., Zion Wilderness; Figure 3). In short, the state of Utah remains largely in control of the fate of air resources within these Class II wilderness areas, which calls into question the “pristine” and “untrammeled” air resources wilderness areas are established to afford.

Air Resources for Whom?

The unequal protection for air resources across Class I and Class II wilderness areas has a variety of implications for wilderness management, ranging from the accumulation of critical loads of criteria pollutants that impact fragile ecosystems to the philosophical challenge to idea of wilderness itself. In this final section, however, we focus on the implications of tiered protections on wilderness visitors. While previous park and protected area research has explored attitudes, values, and behaviors related to clean air and scenic views in various federal land management agency contexts (e.g., Keiser, Lade, and Rudik 2018; Kulesza, Le, Littlejohn, and Hollenhorst 2013; Zajchowski, Brownlee, and Rose 2018), there is currently no empirical research that documents visitor perceptions surrounding differential air resource policies across wilderness distinctions. In other words, we do not know if visitors are aware of the tiered protections afforded to wilderness, if these distinctions matter to them, or if visitor awareness (or lack thereof) leads to different behaviors. For example, would visitors be less likely to visit a Class II wilderness, once they are informed of its “second class” status? Would they engage in different recreation behaviors due to health risks related to exposure to specific pollutants (e.g., particulate matter)? Would they value Class II wilderness resources differently or engage in fewer sustainability practices (e.g., Leave No Trace) in these spaces due to their knowledge of lower federal and state protections? In sum, there are a variety of questions that can be asked by managers and researchers to ascertain the multiple impacts of air resource distinctions on visitor populations.

Additionally, we suggest that it is also prudent to evaluate which types of wilderness air resources are readily available to whom. To revisit the case of Utah, the Class II wilderness areas of the Wasatch Front are relatively accessible to over 80% of Utahns living nearby (e.g., Lindley, Blevins, and William 2018). More specifically, these Class II wilderness areas are perhaps the most accessible wilderness areas for a substantial portion of Utah’s low-income residents and minority communities. Approximately one of every three Utah residents who live below the poverty line reside in Salt Lake County (US Census Bureau 2018). Additionally, Salt Lake County is home to about half (approximately 49%) of individuals who identify as a member of a racial and/or ethnic minority groups living in the state (Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute 2017). Furthermore, the LGBTQIA+ community is another minority community that continues to experience additional barriers to outdoor recreation participation (e.g., Barnfield and Humberstone 2008; Dignan 2002; Parris 2017), and Salt Lake City has the seventh highest percentage of individuals identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender in a list of the largest US metropolitan areas (Newport and Gates 2015). In sum, for members of all these marginalized groups, their closest and most affordable access to wilderness is offered with “second class” air quality protections. For those willing and able to travel across Utah to access first class air resources, this may be less of the concern; however, we imagine the spatial distance between Class I resources and the Wasatch Front is a barrier for many visitors, particularly those of low socioeconomic status. Spatial analysis of visitation patterns across demographic indicators may help to illustrate who is accessing Utah’s Class I and Class II wilderness resources and if disparities between demographics exist that can be attributed the location of Class I wilderness resources.

Nationally, the placement of Class I and Class II wilderness areas begs for a similar analysis. Weber and Sultana’s (2013) work addressing the future of the NPS in a racially diverse America highlighted a 2010 Park Studies Institute survey, which showed low visitation from racial minorities throughout the NPS system. The authors, in part, attribute this to the location of many iconic park units outside of the southeast, where the largest concentration of African Americans reside. We hypothesize that future spatial analysis that evaluates the proximity of Class I and Class II wilderness areas across the United States to different racial groups will illustrate similar findings. In other words, this begs the question of who Class I air resources benefit, and, conversely, who misses out on “pristine” and “untrammeled” air quality. As a case and point, Davis (2019) highlights the limitations placed on black anglers, who visit and reside near Congaree National Park, which gained a Class II wilderness designation in 1988. The author documents that the wilderness designation prevents anglers from engaging in their traditional fishing practices, while allowing for commercial use by predominantly white concessionaires and patrons. Equally problematic is that these anglers, who live near the park, do not benefit from the same air quality protections as visitors to Class I wilderness areas. In other words, not only are they disenfranchised from their traditional fishing practices due to wilderness designation, but they are doubly harmed by not receiving any of air resource benefits that come with a Class I wilderness designation. This case of Congaree highlights the paradoxical results of wilderness designation for local visitors and wilderness-proximate communities.

Figure 5 – Wildfire smoke blankets river rafters on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River at Indian Creek in the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness. Photo by Bethany Craig.

Conclusion

Federal policy creating Class I and Class II wilderness areas pragmatically sought to provide additional resources, protection, and oversight to flagship wilderness areas and national parks across the United States (e.g., Grand Canyon, Shenandoah, Great Smoky Mountains National Parks). However, the separation of Class I and Class II wilderness areas in existing policies deprives Class II wilderness areas of the equivalent resources, protections, and oversight as Class I wilderness. In addition, this two-tiered distinction benefits those able to access clean air resources but may prevent certain populations from similar access. We suggested that second class wilderness areas may be disproportionately situated nearest to urban and minority populations, who bear a greater burden for the health costs of air pollution (Collins and Grineski, 2019). In turn, a change in policy that allows for equal access to Class I resources or affords Class I status to all wilderness areas, regardless of size or date of creation, is worthy of debate.

Finally, we would be remiss to say that, although we call for more research and policy solutions to address these issues, we emphasize the need for critical, action-oriented, and collaborative work on the topic of unequal provisioning of wilderness air resources across lines of class, race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality. Scholarship should not only aim to understand inequities but also to examine realistic and applicable solutions, especially policy solutions, to rectify these inequities. Additionally, we acknowledge that our multiple identities and geographies as authors afford us with various privileges, including white privilege and the economic means to visit and recreate in both Class I and II wilderness areas. Our lack of authors from multiple identities who may be more adversely affected by tiered air resource policies is a limitation in our argument. In sum, we suggest future scholarship in this area will be most beneficial if it is done in collaboration with individuals and communities that are adversely affected by the policies guiding the management of second-class wilderness areas.

CHRIS ZAJCHOWSKI is an assistant professor at Old Dominion University, Program of Park, Recreation, and Tourism Studies; email: czajchow@odu.edu.

ANTHONY DESOCIO is an undergraduate student at Old Dominion University, majoring in park, recreation, and tourism studies and minoring in conservation leadership; email: adeso003@odu.edu.

N. QWYNNE LACKEY is a doctoral student at the University of Utah, Program of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism; email: n.q.lackey@utah.edu.

References

16 U.S.C. 1131-1136, 78 Stat. 890.

42 U.S.C. 7473.

Adams, M. B., D. S. Nichols, C. A. Federer, K. F. Jensen, and H. Parrott. 1991. Screening Procedures to Evaluate Effects of Air Pollution on Eastern Wilderness Cited as Class I Air Quality Areas. Randor, PA: USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. NE-151, 1–33.

Barnfield, D., and B. Humberstone. 2008. Speaking out: Perspectives of gay and lesbian practitioners in outdoor education in the UK. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning 8(1): 31–42.

Branagan, J. 1977. Nondegradation and the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977: Preventing

the graying of America. Urban Law Annual 14: 203–232.

Collins, T. W., and S. E. Grineski. 2019. Environmental injustice and religion: Outdoor air pollution disparities in metropolitan Salt Lake City, Utah. Annals of the American Association of Geographers. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1546568.

Davis, J. 2019. Black faces, black spaces: Rethinking African American underrepresentation in wildland spaces and outdoor recreation. Nature and Space 1–21.

Dignan, A. 2002. Outdoor education and the reinforcement of heterosexuality. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education 6(2): 77–80.

Dustin, D. L., L. Beck, and J. Rose. 2018. Interpreting the Wilderness Act: A question of fidelity. International Journal of Wilderness 24(1): 58–67.

Ebenstein, A., M. Fan, M. Greenstone, G. Hee, and M. Zhouh. 2017. New evidence on the impact of sustained exposure to air pollution on life expectancy from China’s Huai River Policy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(39): 10384–10389.

Environmental Protection Agency 2019a. NAAQS table. Retrieved on May 29, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/criteria-air-pollutants/naaqs-table.

———. 2019b. New source review (NSR) permitting. Retrieved on May 29, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/nsr/prevention-significant-deterioration-basic-information#BACT.

———. 2019c. List of areas protected by the Regional Haze Program: Code of

federal regulations. Retrieved on May 29, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/visibility/list-areas-protected-regional-haze-program.

———. 2013. Guidance for Indian Tribes seeking Class I redesignation of Indian Country pursuant to Section 164(c) of the Clean Air Act. Retrieved March 6, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-09/documents/guidancetribesclassiredesignationcaa082913.pdf.

Hall, S. J., G. Maurer, S. W. Hoch, R. Taylor, and D. R. Bowling. 2014. Impacts of anthropogenic emissions and cold air pools on urban to montane gradients of snowpack ion concentrations in the Wasatch Mountains, Utah. Atmospheric Environment 98: 231–241.

Horel, J., E. Crosman, A. Jacques, B. Blaylock, S. Arens, A. Long… R. Martin. 2016.Summer ozone concentrations in the vicinity of the Great Salt Lake. Atmospheric Science Letters 17: 480–486. Retrieved from doi:10.1002/asl.680.

Keiser, D., G. Lade, and I. Rudik. 2018. Air pollution and visitation at U.S. national parks. Science Advances 4(1613). Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aat1613.

Keller, R. H., and M. F. Turek. 1998. American Indians and National Parks. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute. 2017. Fact sheet: Race and ethnicity in Utah: 2016. Retrieved from https://gardner.utah.edu/wpcontent/uploads/RaceandEthnicityFactSheet2017082 5.pdf.

Kulesza, C., Y. Le, M. Littlejohn, and S. J. Hollenhorst. 2013. National Park Service Visitor Values and Perceptions of Clean Air, Scenic View and Dark Night Skies. Natural Resource Report. Moscow, ID: Park Sciences Unit.

Lindley, B. R., M. D. Blevins, and S. D. Williams. 2018. Cultural meanings and management challenges: High use in urban-proximate wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 24(3): 16–27. Retrieved from https://ijw.org/cultural-meanings-and-management-challenges/.

Mace, B. L., P. A. Bell, and R. J. Loomis. 2004. Visibility and natural quiet in national parks and wilderness areas: Psychological considerations. Environment & Behavior 36(1): 5–31.

Machlis, G. E., and J. B. Jarvis. 2017. The Future of Conservation in America: A Chart for Rough Water. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Malm, W. C. 2016. Visibility: The Seeing of Near and Distant Landscape Features. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier.

Marks, P. M. 1999. In a Barren Land: The American Indian Quest for Cultural Survival, 1607 to the Present. New York: HarperCollins.

Missouri Department of Natural Resources. 2013. Class I, Class II, and Class III Areas. Retrieved on May 30, 2019, from https://dnr.mo.gov/env/apcp/docs/classarea.pdf.

National Park Service. 2002. Air Quality in the National Parks, 2nd ed. Lakewood, CO: AirResources Division.

———. 2019. April 12. Class I Areas. Retrieved on May 29, 2019, from https://www.nps.gov/subjects/air/class1.htm.

Newport, F., and G. J. Gates. 2015. March 20. San Francisco metro area ranks highest in LGBT percentage. Gallup. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/182051/san-francisco-metro-area-ranks-highest-lgbt-percentage.aspx.

Parris, A. 2017. October 18. The first LGBT Outdoor Summit. REI Co-op Journal. Retrieved

from https://www.rei.com/blog/stewardship/the-first-lgbtq-outdoor-summit.

Prucha, F. P., ed. 2000. Documents of United States Indian Policy. Lincoln: University

of Nebraska Press.

Smith, K. K. 2005. What is Africa to me? Wilderness in black thought, 1860–1930.

Environmental Ethics 27(3): 279–297.

Spence, M. 1996. Dispossessing the wilderness: Yosemite Indians and the national park ideal, 1864–1930. Pacific Historical Review 65(1): 2759.

Tessum, C. W., J. S. Apte, A. L. Goodkind, N. Z. Muller, K. A. Mullins, D. A. Paolella, S. Polasky, N. P. Springer, S. K. Thakrar, J. D. Marshall, and J. D. Hill. 2019. Inequity in consumption of goods and services adds to racial-ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved from www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1818859116.

Utah Department of Environmental Quality. 2018. March 1. Ozone: EPA designates marginal nonattainment areas in Utah. Retrieved on May 30, 2019, from https://deq.utah.gov/communication/news/ozone-marginal-nonattainment-areas-utah.

———. 2019. January 8. PM 2.5 State Implementation Plan (SIPs). Retrieved on May 30, 2019, from https://deq.utah.gov/communication/state-of-the-environment-report/pm2-5-state-implementation-plans-sips-2018-state-of-the-environment-report-aq.

United States Census Bureau. 2018. Utah Census Data Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/.

Wager, D. J., and F. A. Baker. 2006. Ozone concentrations in the Central Wasatch Mountains. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 56: 1381–1390.

Weber, J., and S. Sultana. 2013. The civil rights movement and the future of the National Park System in a racially diverse America. Tourism Geographies 15(3): 444–469.

Wilderness Connect. 2019. April 1. Summary fact sheet. Retrieved on May 29, 2019, from https://www.wilderness.net/factsheet.cfm.

Young, T. 2009. “A contradiction in democratic government”: W. J. Trent, Jr. and the struggle to desegregate national park campgrounds. Environmental History 14(4): 651–682.

Zajchowski, C. A. B., and J. Rose. 2018. Sensitive leisure: Writing the lived experience of air pollution. Leisure Sciences. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2018.1448026.

Zajchowski, C. A. B., M. T. J. Brownlee, and J. Rose. 2018. Air quality and the visitor experience in parks and protected areas. Tourism Geographies. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2018.1522546.

Zajchowski, C. A. B., N. Q. Lackey, and G. D. McNay. 2019. “Now is not the time to take a breather”: U.S. public land manager perceptions at the 40th anniversary of the 1977 Clean Air Act Amendments. Society & Natural Resources 32(9): 10003–1020. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2019.1605436.

Zajchowski, C.A.B., M. T. J. Brownlee, M. J. Blacketer, J. Rose, D. L. Rumore, J. M. Watson, and D. L. Dustin. 2019. “Can you take me higher?”: Normative thresholds for air quality in the Salt Lake City Metropolitan Area. Journal of Leisure Research 50(2): 157–180. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2018.1560238.

Read Next

Young Activists: Influencing the Climate Change Movement

As 2019 closes, it is noteworthy to recognize the influence and impact of Greta Thunberg, the Swedish climate activist.

The Cognitive Costs of Distracted Hiking

What do smartphones, global positioning systems, Spot Locator Beacons, navigation apps, and other technological innovations mean for the future of outdoor recreation, and, especially, the future of wilderness?

Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks: A Case Study of Mining Claim History in Four Adjacent National Forest Wilderness Areas

The area of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), more recently called Greater Yellowstone Area, was first delineated by Craighead (1977) as representing the continuous essential habitat for the grizzly bear