Following the route of the Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail

Understanding the Role of Social Interactions During Different Phases of the Thru-Hiker Experience

Science & Research

August 2020 | Volume 26, Number 2

PEER REVIEWED

ABSTRACT

Thru-hiking has been on a dramatic rise, spurring hikers to venture onto increasingly remote and challenging trails over extended periods of time. Despite the recent popularity of thru-hiking, there is little known about how social interactions across the different phases of the recreational experience. This study addressed these gaps by investigating the thru-hiker experience of the Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail (PNNST), a trail best known for its remoteness, rugged features, and solitude. Multi-phase semi-structured interviews were conducted with 42 of the 2017 PNNST thru-hikers before their hike (anticipation phase), directly after completion (on-site phase), and two months after completion (recollection phase). The results illuminate that while the PNNST is a relatively low-usage trail, the feeling and desire for community was prevalent during different stages of the thru-hike and social relationships contributed to hikers’ ability to cope with challenges during the hike. Additionally, the research suggests that social media platforms contribute to the preparation prior to the hike and maintaining relationships during the transition back to everyday life after the thru-hike. This study’s findings contribute to the conceptual understanding of how the social experience is integral and diverse to various phases of the thru-hiking experience.

Thru-hiking has grown rapidly over the past decades (Berg 2015) and can be defined as an individual hiking the entire length of an extended trail in a continuous journey, departing from one terminus of the trail, and hiking unaided to the other terminus (Mills & Butler 2005; Bruce 1995). In the United States, there are eleven National Scenic Trails including the popular Appalachian Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail. These trails were established through the National Trails System Act [NTSA] (2009) with the aim to provide the greatest opportunity for outdoor recreation and conservation of scenic, natural, historical, or cultural qualities along the trails. The variety of geographic locations and other experiential characteristics contribute to diverse opportunities and challenges for thru-hikers and managers on these trails. There has been research addressing the experience of popular long-distance trails (Peterson, Brownlee, and Marion 2018; Hitchner, Schelhas, Brosius, and Nibbelink 2019; Robertson and Goetz 2017); however, there has been limited research exploring how the social interactions within the thru-hiking community impact the preparation and response to challenges before and during the thru-hike and how these social interactions can support transition of hikers back to everyday life after this immersive experience. To address this gap, our study investigated the social aspects of the thru-hiker experience before the hike, reflections on during the hike, and after the hike on the Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail (PNNST).

The Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail

The PNNST became a National Scenic Trail in 2009 and stretches 1,200 miles from western Montana on the eastern border of Glacier National Park to the Olympic Peninsula of Washington. The PNNST passes through six designated wilderness areas, three national parks, seven national forests, and through over twenty towns along the route (PNTA 2020). Traversing through diverse ecosystems, including high alpine, high desert, and rainforest, PNNST thru-hikers often have opportunities to encounter grizzly and black bears, wolves, moose, mountain goats, and other wildlife species unique to the region (Figure 1).

The overall management of the PNNST is overseen by the U.S. Forest Service and is also supported by the Pacific Northwest Trail Association (PNTA) that defines their mission as “to protect and promote the Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail, and to enhance recreation and educational opportunities for the enjoyment of present and future generations” (PNTA 2020). Thru-hiking has been increasing in popularity each year and the number of thru-hikers on the PNNST is also estimated to increase in usage in the coming years. The majority of hikers who attempt the trail start from Chief Mountain, Montana in late June or early July and take 60-75 days to arrive at Cape Alava, Washington (PNTA 2020). Based on visitor use monitoring during the 2018 field season, there have been slight increases in thru-hikers, but not to the level of growth experienced by the Appalachian Trail or the Pacific Crest Trail, two of the most popular thru-hiking trails in the United States.

Social Aspects across Phases of the Recreational Experience

Outdoor recreation encompasses multiple phases (Clawson and Knetch 1966; Hammitt 1980) and involves dynamic interactions through a lived, personal experience (Stewart 1998; Borrie and Roggenbuck 2001). The phases include anticipation phase, travel to phase, the actual on-site experience phase, the travel-back phase, and the recollection phase (Clawson and Knetch 1966). Social interactions occur at various phases and can influence the short and long-term impacts of recreation. In the anticipation phase, individuals need to prepare for a safe and enjoyable experience. This phase is particularly important for individuals who do not have prior experience with the recreation activity and for recreational activities that require in-depth preparation and specialization. The level of specialization is influenced by required equipment, skillset, and amount of previous experience (Bryan 1977; Tsaur and Liang 2008). Thru-hiking requires adequate preparation as an immersive and specialized recreation activity. The anticipation stage can support interactions between experienced and non-experienced recreationists to prepare for the on-site phase and support the successful completion of the thru-hike.

In the actual on-site experience, the social component can be a central part of the overall experience (Peters, Elands, and Buijs 2010; Lu and Schuett 2014). Individuals can recreate with others (e.g. hiking with a friend) or meet new recreationists during the activity (e.g. meeting an individual on the trail). Some recreationists seek limited social interactions; while social exchanges can be a motivator for others to participate in the recreation activity (Whiting, Larson, Green, and Kralowec 2017; Chang, Wray, and Lin 2014). For thru-hiking, many individuals set out on the trail without other hikers or a hiking group; yet, there is an underlying supportive and welcoming community aspect to thru-hiking that contributes to social interactions (Littlefield and Siudzinski 2012). There has been more recent research exploring the social worlds of thru-hikers with particular emphasis on the segmentation of different types of hikers on the trail based on their motivations and social interactions (Lum, Keith, and Scott 2020). In addition to the social interactions with other recreationists, thru-hikers frequently visit trail towns and engage with local communities, other hikers, or trail angels (Rush 2002). Many of these non-hikers provide support and a sense of community to thru-hikers as they travel through the area (Bratton 2012; Lum et al. 2020).

The social aspects of recreation can persist in the recollection phase after the activity is completed. Recreationists share their experience with others who were directly involved with the activity (e.g. other recreationists) or with others in their life who were not involved in the recreation activity (e.g. friends and family). For thru-hiking and other types of recreation that are immersive and take place over extended periods of time, there can be difficulty when transitioning back to everyday life. Turley (2011) found that thru-hikers experience a sense of loss of the intimate sense of community on the trail. This period of reflection after the completion of the recreational activity is important to the overall experience and can inspire deeper and long-term impacts from recreation (Duerden, Witt, and Taniguchi 2012). However, there are very few studies that explore the role of long-term social connections in the thru-hiking community.

Solitude, Social Cohesion, and Thru-Hiking

Wilderness areas are managed for a solitude experience and many recreationists seek these areas specifically for solitude (Hall 2001; Dawson 2004). Long distance trails often encompass wilderness areas; thus, solitude is a key aspect of the thru-hiking experience. Thru-hiking is often portrayed as a personal journey (Zealand 2007; Robertson and Goetz 2017; Robinson 2013) and has been compared to a spiritual “pilgrimage that is done alone, but also communally” (Hitchner et al. 2019 p. 88). However, solitude does not equate to an absence of all social interactions (Dawson 2004).

Recent studies indicate the emergence of hiking subcultures and a unique social element for long-distance trails (Fondren and Brinkman 2019). This subculture is often associated with the specific long-distance trail and hikers have a shared language, behaviors, and attitudes towards their activities on and off the trail (Fondren and Brinkman 2019). Relatedness, “the need to feel belongingness and connectedness with others” (Ryan and Deci 2000 p. 73), has overlap with subculture characteristics; however, it is important to note that hikers can be autonomous while also having a social community. The general emphasis on independence and solitude in the thru-hiking experience may underestimate the role of social interactions, relatedness , and social cohesion to the phases of the thru-hiking experience.

Social cohesion refers to how individuals in a social system identify with values, norms, and beliefs (Durkheim 1972). Positive relationships, acceptance, and belonging are key aspects of social cohesion (Forrest and Kearns 2001; Jennings and Bamkole 2019) in addition to place attachment and empowerment (Jennings and Bamkole 2019). Social cohesion exists when individuals are experiencing positive outcomes from group membership and there are interpersonal interactions that support these conditions (Friedkin 2004). The level of social cohesion within a group is influenced by the attractiveness of group membership, the structural conditions among the group, and the extent to which individuals’ identity is associated with a particular group (Friedkin 2004).

The sociological concepts of social cohesion can occur during recreational experiences (Peters et al. 2010; Jostad, Paisley, Sibthorp, and Gookin 2013). Social cohesion has been examined in outdoor recreation; however, findings have been mixed. For example, some studies have found a positive relationship between social cohesion and mental health in recreational settings (Maas, Van Dillen, Verheij, and Groenewegen 2009; de Vries, Van Dillen, Groenwegen, and Spreeuwenberg 2013); while other studies found no relationship between social interaction and emotional wellbeing (Korpela, Borodulin, Neuvonen, Paronen, and Tyrvainen 2014). In the context of urban parks, most social interactions were considered cursory, but that may be attributed to the characteristics of an urban park experience (Peters et al. 2010). To expand the understanding of social interactions of thru-hiking on a long-distance trail, this study interviewed thru-hikers on the Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail during different phases of their recreational experience.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were used to collect data from thru-hikers on their social experience during the anticipation, on-site, and recollection phases (Siedman 2006). The three phases of interviews included: 1) before individuals begin their thru-hike (anticipation), 2) after thru-hikers finished their hike (on-site), and 3) two months after the hiker finished their time on the trail (recollection).

The anticipation interview phase took place prior to thru-hikers beginning their journey. This interview focused on demographic information and previous hiking experience, attractive qualities of the trail, motivations for thru-hiking, social expectations of the trail experience, preparation for the thru-hike, and information about plans to hike solo or in a group. The second on-site phase of interviews took place directly after participants finished the thru-hike. Researchers asked hikers about the most rewarding and challenging parts of the experience, overcoming challenges during the hike, and the social experience on the trail and in the trail towns. The third and final recollection interview took place two months following the second interview. This timing was chosen to represent a time that allowed for some reflection and readjustment to off-trail life, but also was within a feasible time to retain participation. The third interview asked about the challenges and ease of adjustment back into everyday life, skills gained from the experience, most memorable portions of their PNNST experience, sustained contact with others they met on-trail, and trail-related social media and online communication. It is important to note that are often differences between how individuals actually experience leisure compared to a reflection on the experience (Zajchowski, Schwab, and Dustin 2017).

Interview participants were recruited through the support of the Pacific Northwest Trail Association (PNTA). The Facebook group “PNT Class of 2017” included 79 members of thru-hikers for the 2017 hiking season, However, there was no ability for the researchers to confirm that these members all completed the hike. According to the PNTA, approximately 65-75 hikers attempted to complete the entirety of the trail in 2019 (PNTA 2020). The PNTA manages the Facebook page and included multiple posts on the Facebook page encouraging voluntary participation in the study with the researcher’s contact information to setup an initial interview. A second recruiting strategy for the study included the voluntary registration of thru-hikers through the PNTA’s webpage. Once hikers were registered, they were presented with a message to voluntarily participate in the study through an email message. USFS and PNTA publicly endorsed and supported participation in the interviews. In addition to recruitment via Facebook and PNTA webpage, interview participants were recruited during trail-related encounters with thru-hikers during the thru-hiking season when the research was conducting monitoring on the trail. If hikers agreed to participate in the study, they were asked to provide an email to be contacted at a later time by the researcher to setup an interview.

Interviews from 42 participants are included in this study. Interviews were conducted primarily by phone although some in-person interviews took place if the participants lived in close proximity. All interviews were recorded and transcribed and all responses remained anonymous in the analysis (Siedman 2006). Interviews were transcribed and coded using NVivo. Six researchers independently coded three interview transcriptions and developed their own list of codes (Berg 1989). Independent coding was synthesized to create a standard code list with strong intercoder reliability (Siedman 2006). This standard code list was applied by a single coder to the remainder of the interviews. Coded data from across the three phases of interviews were pooled and thematically analyzed. Themes were arrayed along the same temporal experience spectrum as the interviews.

Results

Table 1 presents the interview respondents by gender, age, and where they traveled from to hike the PNNST. Half of the respondents had previous thru-hiking experience, 43% were from the west, 64% were male, and 60% were ages 18-35.

Results below are discussed in order of their appearance in the anticipation, on-site, and recollection phases of the thru-hike experience. In each section, the relative frequency of themes and ideas being expressed by respondents is reported.

Anticipation Phase (pre-hike)

Motivations and social connections

Before hikers began the trek, they shared motivations for why they chose to thru-hike many of which were connected to individual goals and desires for escape from society. The PNNST has a reputation as rugged, remote, and relatively untraveled compared to other long distance trails. One hiker shared, “I’ve been told it’s more of a wild feeling. It’s really remote.” Self-drive (i.e. self-determination, the desire to live life to the fullest, always wanting to do a thru-hike) was prevalent among thru-hikers (56%) and this was particularly a popular motivator for respondents 18-35 years old. One thru-hiker said: “overall I kind of want to do this for myself.”

Many other hikers (40%) were motivated by the aspect of escape (i.e. escape from consumerism, daily life, society, technology). This idea of escape was particularly prevalent in thru-hikers over 56 years old. One of the thru- hikers expresses their motivation to thru-hike as: “I’m hoping this will kind of shake me up a little bit, and help me to put one foot forward in that aspect too. One foot in front of the other as far looking for what’s next.” A third theme focused on how participants were motivated by personal connections with others to the PNNST (25%). This theme included personal connections with people who had previously hiked the trail. For example, a hiker shared: “I’ve known about it [the PNNST] my entire life … so I took that book that my grandpa had 11 years ago of the trail and decided that that’s what I wanted to do to kind of honor him…”

Preparation and social connections

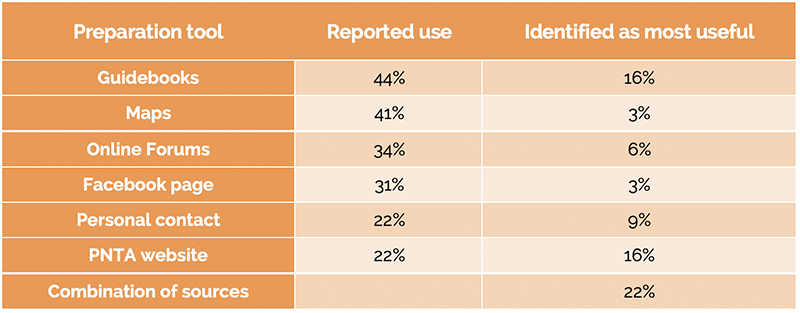

Preparing for a 1,200 mile expedition entails many aspects and requires a multitude of sources to gather that information (Table 2). While guidebooks and maps are commonly thought of as the most useful for planning a thru-hike, social platforms such as online forums (34%) and Facebook (31%) are being utilized in the planning process as well. For the PNNST, there are Facebook pages where hikers, potential hikers, and PNTA members can share ideas and ask questions. One hiker described the Facebook page as an opportunity to get information from knowledgeable hikers: “just talking to those trail experts and people who’ve done it before doing their advisement bit. It’s probably been the single most helpful thing.” Personal contact with former thru-hikers and the use of the PNTA webpage was also recognized as a resource prior to the hike. While these were the most commonly used resources by hikers, guidebook and the PNTA website were the most useful sources with recognition that most hikers use a combination of these resources. One hiker explains “I don’t think I can point to any one thing just because everything is kind of spread out, so you can get little bits of information from all over in different places.”

Anticipation Phase (pre-hike) expectations vs. On-Site Phase (post-hike) experience

The PNNST has a reputation as a low-use trail with very little known about social interactions before, during, and after the thru-hike. Fifty-three percent of pre-hike interviewees were planning to hike the trail alone. Many hikers (65%) cited that that they could not find anyone to join them. One hiker shared, “I figured if I waited to try to find somebody to do it [hike the trail] with, then I might never get around to it, so I just decided to do it myself.” Other hikers (35%) found that they are comfortable or prefer to hike by themselves, described as: “I enjoy going solo. It [hiking alone] kind of opens up your experiences when you’re solo.” Twenty-three percent of those hiking alone also noted that they prefer their own hiking style to those of a group. A hiker described the choice as: “I don’t like to have to be tied down to someone else’s plans, so if I hike and I find people who are compatible, then I’ll hike with them, but I never want to go into a hike with the expectation that I’ll stay with someone for the whole thing.”

Despite the large amount of pre-hike interviewees that planned on hiking alone, 46% of pre-hike interviewees planned on hiking with a group. Many of these group hikers (33%) had a fear of being alone or hiked in groups for safety reason. In particular, one PNNST hiker described their apprehension of hiking alone in grizzly habitat: “I’m really afraid of grizzly bears, really afraid. Yeah, so I wouldn’t even consider hiking through grizzly country by myself. It just wouldn’t be enjoyable for me.” Other notable reasons for choosing to hike with others were that they enjoy hiking with their partner (13%) and that their friends wanted to join them (20%). Within pre-hike interviewees, 7% more men were choosing to hike alone than women.

Since the PNNST is significantly less travelled than other National Scenic Trails like the AT and the PCT, thru-hikers have a variety of expectations about the social experience during the hike. During pre-hike interviews, 44% of individuals thought that they would not see many other people on the trail. However, 53% of interviewees reported that they also wanted to meet people or form hiking groups during the hike. Many interviewees (21%) also stated that they thought the PNNST would be a different social experience than other thru-hikes: “I don’t feel like in my head it’s going to be the same as the PCT where you’re walking with groups of people that you meet along the way.” There was a small percentage (9%) who expressed their desire to not have a social experience: “We’re hoping to minimize social experience…mostly we’re wanting to enjoy nature on our own.” Because of its reputation as a low-use trail, 28% of thru-hikers expected to experience solitude: “I’m definitely expecting it to be more solitary than the past couple [thru] hikes.” Another 19% of participants expected to have a reflective experience on the PNNST. One hiker shared their desire for: “…that really deep inner reflection. I’m definitely expecting to get that and more from this hike”.

Despite many hikers planning to hike alone, 73% of post-interview respondents stated that they joined with others during the hike. Reflecting back on the hike, many hikers found their expectations were surpassed when it came to social interactions with people. For example, one hiker shared, “I didn’t have expectation for the people that we would meet or like the trail angels, but they were all phenomenal. We met some really amazing people and that was really cool”. When asked about the most rewarding aspects of the thru-hike, 32% of hikers identified the social experience: “I think the friends that I made along the trail. That was hugely rewarding. I just had a fantastic time with other hikers”. The rewarding social experience for PNNST thru-hikers not only includes other hikers, but also the interactions within trail towns and with trail angels: “the community support was much more extensive in breadth and depth than I expected.”

On-Site Phase (post-hike): Coping with challenges

Thru-hikers on the PNNST faced a myriad of challenges during their time on the trail and hikers identified a variety of coping strategies. Loneliness emerged as a challenge in 8% of post-hike interviews. One hiker described their struggles during the thru-hike as: “There was a lot of feeling of loneliness on the trail for me personally and it’s something new for me coming from the PCT last year where there’s a lot of people on the trail.” Fifty-one percent of post-hike interviewees stated social aspects as one of their mechanisms to cope with challenges on the trail. One thru-hiker describes utilizing social tools to succeed: “When things were hard, it was never like I was thinking, ‘Uh, I quit.’ I think it’s good having a partner.” Reliance on hiking partners was one of the most frequently referenced (39%) coping strategies during the hike. According to many hikers, their hiking partner made it easier to tackle the challenges that they encountered:

I think having people with me was a big deal this time around going through. If I didn’t have somebody else hiking with me on some of these bushwhacks, I would have just lost it you know? I’d have been so pissed off, but you go with somebody and it’s not as bad. You can laugh about it a little bit more. For me, that’s big.

The social component of the thru-hike was mentioned by 51% of hikers during the interviews two-month after completion of the hike. One hiker stated “it’s always so much easier to suffer with other people.” Additionally, support from the PNTA and locals in trail towns were cited by 14% of hikers as a strategy to cope with challenges, with one hiker noting that they were “super helpful” in dealing with struggles on the trail. Trail towns were noted by several thru-hikers in their two-month post-hike interviews as an aspect that was especially memorable about their PNNST experience: “I talk a lot about the small little towns and the great people that I’ve met along the way.” While thru-hiking the PNNST includes many beautiful landscapes, the social aspect of trail life appears to also leave a lasting impact on those who undertake this journey.

Recollection Phase: Social relationships

In the interviews with hikers two months after completion of the trail, thru-hikers were asked about their transition back to everyday life. Individuals who had prior experience with thru-hikes reported an easier transition back to routines of daily life than those who had not previously completed a thru-hike. Thru-hikers with previous experience had 56% reporting challenges in readjustment compared to 83% of hikers with no previous thru-hike experiencing challenges in readjustment. One hiker reflected on the difficulty in transitioning from the way of life on the trail as “when you’re in the wilderness a lot, you appreciate people on their individual basis, you know each person. But when I’m in the city around big groups of people, I have noticed it’s almost like a post-traumatic syndrome.”

In the two-month post-hike interviews, 93% of respondents indicated that they were still in contact with people that they met on the PNNST. Eighteen percent of hikers only maintained contact with the individuals with whom they hiked with on the PNNST while 14% of hikers also maintained contact with trail angels two months after the trail. Thru-hikers varied in their modes of communication. Facebook was the most popular contact method with 46% of respondents noting that they used the site to keep in touch and when combined with Instagram (10%), the majority of respondents used social media for post-hike communication. For example, a hiker explained “so far it’s mainly with Facebook. I have called and checked in on a couple of people just to see how they were doing. The PNT hikers Facebook page has been a good place for all of us to stay connected.” Texting (39%), phone calls (21%), and email (11%) were also common methods of communication.

Social media usage related to the PNNST was also asked about in post-hike interviews. Fourteen percent of participants reported using social media strictly for sharing photos of their experience: “I kind of blogged throughout the trip, used my Facebook to promote it . . . I think I pretty much have wrapped everything up with that. I don’t think I’ll really be posting anything more going forward.” Many thru-hikers (24%) used social media to reach a broader audience and to keep in touch with other hikers and trail angels (14%). Finally, there were 24% of interviewees who reported that they were not engaging on social media about their experience on the PNNST. One hiker stated: “I don’t know, I may post another photo or two. But I don’t think I’ll keep talking about it for my whole life”.

Discussion

Importance of social cohesion on low-use trails

This study explored the social aspects of the thru-hiker experience before (anticipation phase), during (on-site phase), and after the completion (recollection phase) of the PNNST hike. While PNNST hikers were drawn to the trail for its reputation of low use and the opportunity for solitude in a unique and dynamic landscape, the social aspect of thru-hiking was identified as the most rewarding part of their experience. Compared to popular, high-use trails like the Appalachian Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail, the PNNST offers a distinctly different type of long-distance trail experience for thru-hikers (Figure 2). Although the majority of interviewees had expectations or desires of hiking alone, most of these solo hikers joined other hikers on the trail. This study emphasized the importance of social components to helping hikers overcome challenges and have a positive, transformative experience.

Figure 2 – The PNNST offers a distinctly different type of long-distance trail experience for thru-hikers

The findings demonstrated the robust and tight-knit nature of the PNNST hiking community. Many aspects of social cohesion such as positive relationships, belonging and identity with a group, and place attachment (Forrest and Kearns 2001; Jennings and Bamkole 2019; Friedkin 2004) were present for PNNST hikers. Additionally, the findings showed a relationship between social connections and the ability to cope with challenges and transitions back to everyday life. Thus, mental wellbeing was enhanced through social cohesion which has been found in other recreational settings (Maas et al. 2009; de Vries et al. 2013).

This study revealed that social cohesion and social interactions are not just part of high-use long distance trails like the Appalachian and Pacific Crest Trails, but are also integral to the thru-hiking experience on low-use long distance trails.

Shared experiences create bonds and aspects of community (Arnold 2007) which was evident by how many PNNST hikers reported extended stays in trail towns specifically to socialize with other hikers, trail angels, or others in the community. The subculture of the PNNST thru-hikers illustrated the importance of relatedness (Ryan and Deci 2000) and the unique connections that form in association with the recreational activity and the trail (Fondren and Brinkman 2019). This study revealed that social cohesion and social interactions are not just part of high-use long distance trails like the Appalachian and Pacific Crest Trails, but are also integral to the thru-hiking experience on low-use long distance trails.

Social interactions across recreational phases

Outdoor recreation encompasses multiple phases (Clawson and Knetch 1966; Hammitt 1980) and this study focused on the anticipation, on-site, and recollection phases of the PNNST thru-hiking experience. The findings suggested distinct roles for social interactions across recreational phases. In the anticipation phase, interviewees reported using a combination of sources including online forums, social media, and personal contact with potential or experienced hikers. This pre-hike engagement was largely focused on information exchange and logistical planning which is common for experiences such as RV trips (Fjelstul and Severt 2011) and tourism (Xiang, Wang, O’Leary, and Fesenmaier 2015; Amaro, Duarte, and Henriques 2016). PNNST hikers required ample time for planning especially for inexperienced hikers that are not familiar with the geographic area; thus, the distinct equipment and skills required of thru-hiking highlighted the role of previous experience and external support for this specialized recreation activity (Bryan 1977; Tsaur and Liang 2008).

Thru-hikers also stated how their social relationships provided support to cope and overcome physical and mental challenges experienced during the hike or on-site phase of the thru-hiking experience. While social groups are identified as a coping mechanism (Coble, Selin, and Erickson 2003), there has been limited application to the specific challenges of thru-hikes. Immersive outdoor wilderness courses, such as Outward Bound and the National Outdoor Leadership School, have emphasized the role of group dynamics in knowledge transfer and coping with challenges in a wilderness setting (Sibthorp, Furman, Paisley, Gookin, and Schumann 2011; Goldenberg and Pronsolino 2008). The core concepts from these programs may be applicable to the thru-hiking experience especially to navigate the plethora of mental and physical challenges during the hike.

The study findings indicated that the social experience for PNNST thru-hikers extended into the recollection phase. The continuity of group membership has been noted as an important aspect of social cohesion research (Friedkin 2004). Nearly all hikers reported that they maintained thru-hike contacts and relationships several months after they completed the trail. Many PNNST thru-hikers shared the challenges of transitioning back to everyday life off the trail, similar to Turley’s (2011) study, and how their connections with the trail community helped to cope with these challenges particularly for novice hikers. Findings suggest a unique subculture of PNNST nested within the broader thru-hiking sub-culture. This idea of nested subcultures connected to geographic landscapes underlined the unique aspects of thru-hiking that occur in diverse long-distance trail settings (Fondren and Brinkman 2019). Unfortunately, many thru-hikers are distanced geographically and have limited in-person contact after completion of the hike. Online forums play a critical role in engaging recreation communities (Cong et al., 2008; Ziegler et al., 2014) and may be particularly important to the thru-hiking community for maintaining relationships in months and years beyond the hike’s completion.

Social media as a tool for social interactions

Many hikers want to escape the use of technology when on the trail due to its proliferation in modern society (Ptasnik 2015). However, technology is changing the relationship between recreationists and the landscape (Martin 2017; Dustin, Beck, and Rose 2017; Dustin, Amerson, Rose, and Lepp 2019). Social media has become an avenue for creating and maintaining community during the different phases of thru-hiking. Millions of individuals engage in social media and the numbers continue to rise (Correa, Hinsley, and De Zuniga 2010). Thru-hikers travel from all over the country and world and often do not have opportunities to meet another hiker in-person before they start the hike. Online forums and sharing networks are helpful for sharing in-depth information including recreation groups like thru-hikers (Cong, Wang, Lin, Song, and Sun 2008).

Thru-hiking has many social media sites that are being used regularly by potential, current, or former thru-hikers. For example, “WhiteBlaze.net”, is a site focused on Appalachian Trail hiking, and has thousands of members with millions of posts from both thru-hikers and people interested in the trail (Ziegler, Paulus, and Woodside 2013). Additionally, there are Facebook pages dedicated to the specific years of a thru-hike (e.g. PNNST Class of 2019). As social media and the internet become more prolific, they increase access of information to individuals exploring new recreational opportunities (Jacoby-Garrett 2019). Hikers typically utilize social media for planning purposes (i.e. gear, scheduling, finances) in the anticipation phase, in the on-site phase for updates in the on-site phase, and for memories of the trail and anecdotes about the experience in the recollection phase (Kotut, Horning, Steltard, and McCrickard 2020). Additional studies demonstrated hikers’ use of cell phones and other forms of technology when on the trail (Dustin et al. 2017; Dustin et al. 2019). Although this PNNST study did not specifically focus on the use of technology on and off the trail, PNNST thru-hikers did share their use of social media before and after the hike. However, there is a need for future research on the social media use for PNNST thru-hikers across the phases of the recreational experience.

Managers and other supporting organizations of long-distance trails can utilize social media and internet forums to provide information, engage with potential and current hikers, and promote stewardship of trails and other key issues beyond the hike. The PNTA currently uses their online forums and social media sites to provide updates and information (e.g. trail closures, wildfires, etc.), but there could be additional opportunities for stewardship and continued engagement with the trail community. This strategy has been utilized by other types of recreation (Landon, Kyle, Van Riper, Schuett, and Park 2018; Larson, Cooper, Stedman, Decker, and Gagnon 2018a; Larson, Usher, and Chapmon 2018b) and can be applied to stewardship of long-distance trails. The transboundary nature of long-distance trails may require a variety of pro-environmental behaviors that can promote stewardship ranging from local trail maintenance, support of trail associations, advocacy for establishment of trails, to spreading awareness on various ecological issues associated with the trail and respective region; however, there is a need for further research to better understand this relationship (Thapa, 2010).

Conclusions

The purpose of this research was to better understand the role of social interactions through various phases of the thru-hiking experience. First, the study’s findings illuminate that thru-hiking is a community, even on the PNNST where the usage is relatively low and hikers expected minimal social interactions. Second, the social experiences are integral to different phases of the recreational experience including planning, coping with physical and mental challenges during the hike, and transition back to everyday life after the hike. Third, social media is a useful tool to support social interactions across the phases of the thru-hike.

As with all research studies, there are limitations and recommendations for future research. The recruitment process of this study may have limited some of the hiker participation as it was largely targeted to online forums and websites. A number of individuals did not respond to requests for a post-hike interview due to email complications, possibly not finishing the trail, or deciding that they no longer wished to participate in the study. Additionally, hikers were asked to reflect on their experience on the trail which may influence the findings (Zajchowski, et al. 2017). A final limitation is the study’s primary focus on the PNNST as other extended trails have differing characteristics that may limit the generalizability of the findings. This study offers the potential for development of a survey and scale focused on social aspects of the thru-hiking experience, which can provide insight to broader trends if applied to diverse thru-hiking audiences and contexts.

This research contributes valuable information to understanding the social aspects of thru-hiking. While there is ample research looking at social aspects of other types of recreation, there is limited application to the thru-hiking context which is unique from many other types of experiences due to the immersive and longitudinal qualities of the experience and the transboundary geographic context. The study’s findings provide a foundation for future research to expand various lines of inquiry and provide insight for long-distance trail managers and trail associations to utilize the thru-hiking social community to (1) strengthen hiker preparation in the anticipation phase; (2) help hikers cope with challenges on-site during the hike and supporting social cohesion; and (3) maintain relationships with the hiking subculture in the recollection phase to facilitate future stewardship behavior and long-term connections to the trail and the trail community.

About the Authors

TAYLOR COLE is an outdoor recreation coordinator at Idaho State University, Program of Outdoor Education; email: coletay2@isu.edu

JENNIFER THOMSEN is an Assistant Professor at University of Montana, Parks, Tourism, and Recreation Management Program; email: Jennifer.thomsen@umontana.edu

References

Amaro, S., P. Duarte, and C. Henriques. 2016. Travelers’ use of social media: A clustering approach. Annals of Tourism Research 59: 1-15.

Arnold, K. D. 2007. Education on the Appalachian trail: What 2,000 miles can teach us about learning. About Campus 12(5): 2-9.

Berg, A. 2015. “To conquer myself”: The new strenuosity and the emergence of “Thru-hiking” on the Appalachian Trail in the 1970s. Journal of Sport History 42(1): 1-19.

Borrie, W. T. and J. W. Roggenbuck. 2001. The dynamic, emergent, and multi-phasic nature of on-site wilderness experiences. Journal of Leisure Research 33(2): 202-228.

Bratton, S. P. 2012. The spirit of the Appalachian Trail: Community, environment, and belief.

Knoxvilee: Univ. of Tennessee Press.

Bruce, D. 1995. The Thru-hiker’s Handbook. Center for Appalachian Trail Studies.

Bryan, H. 1977. Leisure value system and recreational specialization: The case of trout fishermen. Journal of Leisure Research 9(3): 174–187.

Chang, P. J., L. Wray, and Y. Lin. 2014. Social relationships, leisure activity, and health in older adults. Health Psychology 33(6): 516.

Clawson, M. and J. L. Knetsch. 2011. Economics of Outdoor Recreation. New York: RFF Press.

Coble, T. G., S. W. Selin, and B. B. Erickson. 2003. Hiking alone: Understanding fear, negotiation strategies and leisure experience. Journal of Leisure Research 35(1): 1-22.

Cong, G., L. Wang, C. Y. Lin, Y. I. Song, and Y. Sun. 2008. Finding question-answer pairs from online forums. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. 467-474.

Correa, T., A.W. Hinsley, and H. G. De Zuniga. 2010. Who interacts on the Web?: The intersection of users’ personality and social media use. Computers in Human Behavior 26(2): 247-253.

Dawson, C. P. 2004. Monitoring outstanding opportunities for solitude. International Journal of Wilderness 10(3): 12-14.

De Vries, S., S. M. Van Dillen, P.P. Groenewegen, and P. Spreeuwenberg. 2013. Streetscape greenery and health: stress, social cohesion and physical activity as mediators. Social Science & Medicine 94: 26-33.

Duerden, M. D., P. A. Witt, and S. Taniguchi. 2012. The impact of postprogram reflection on recreation program outcomes. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 30(1): 36-50.

Durkheim, E. 1972. Emile Durkheim: Selected Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dustin, D., K. Amerson, J. Rose, and A. Lepp. 2019. The cognitive costs of distracted hiking.

International Journal of Wilderness 25(3): 12-23.

Dustin, D., L. Beck, and J. Rose. 2017. Landscape to techscape: Metamorphosis along the

Pacific Crest Trail. International Journal of Wilderness 23(1): 25-30.

Fjelstul, J. and K. Severt. 2011. Examining the use of RV travel forums for campground searches. Journal of Tourism Insights 2(2): Article 4.

Fondren, K. M. and R. Brinkman. 2019. A Comparison of Hiking Communities on the Appalachian and Pacific Crest Trails. Leisure Sciences, 1-18.

Forrest, R. and A. Kearns. 2001. Social cohesion, social capital and the neighbourhood. Urban Studies 38(12): 2125-2143.

Friedkin, N. E. 2004. Social cohesion. Annual Review of Sociology 30: 409-425.

Goldenberg, M. and D. Pronsolino. 2008. A means-end investigation of outcomes associated with Outward Bound and NOLS programs. Journal of Experiential Education 30(3): 271-276.

Hall, T. E. 2001. Hikers’ perspectives on solitude and wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 7(2): 20-24.

Hammitt, W. E. 1980. Outdoor recreation: Is it a multi-phase experience? Journal of Leisure Research 12(2): 107-115.

Hitchner, S., J. Schelhas, J.P. Brosius, and N.P. Nibbelink. 2019. Zen and the art of the selfie stick: Blogging the John Muir Trail thru-hiking experience. Environmental Communication 13(3): 353-365.

Jacoby-Garrett, P. 2019. Social media enhances inclusivity. National Recreation and Park

Association. Retrieved on November 10, 2019, from https://www.nrpa.org/parks-recreation-magazine/2019/october/social-media-enhances-inclusivity-outdoors/.

Jennings, V. and O. Bamkole. 2019. The relationship between social cohesion and urban green space. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16(3): 452.

Jostad, J., K. Paisley, J. Sibthorp, and J. Gookin. 2013. The multidimensionality of group cohesion: A social network analysis of NOLS courses. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership 5(2): 131-135.

Korpela, K., K. Borodulin, M. Neuvonen, O. Paronen, and L. Tyrväinen. 2014. Analyzing the mediators between nature-based outdoor recreation and emotional well-being. Journal of Environmental Psychology 37: 1-7.

Kotut, L., M. Horning, T. L. Stelter, and D. S. McCrickard. 2020. Preparing for the

Unexpected: Community Framework for Social Media Use and Social Support by Trail Thru-Hikers. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Landon, A. C., G. T. Kyle, C. J. Van Riper, M. A. Schuett, and J. Park. 2018. Exploring the psychological dimensions of stewardship in recreational fisheries. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 38(3): 579-591.

Larson, L. R., C. B. Cooper, R. C. Stedman, D. J. Decker, and R .J. Gagnon. 2018a. Place-based pathways to proenvironmental behavior: Empirical evidence for a conservation–recreation model. Society & Natural Resources 31(8): 871-891.

Larson, L. R., L. E. Usher, and T. Chapmon. 2018b. Surfers as environmental stewards: Understanding place-protecting behavior at Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Leisure Sciences 40(5): 442-465.

Littlefield, J. and R. A. Siudzinski. 2012. ‘Hike your own hike’: equipment and serious leisure along the Appalachian Trail. Leisure Studies 31(4): 465-486.

Lu, J. and M. A. Schuett. 2014. Examining the relationship between motivation, enduring involvement and volunteer experience: The case of outdoor recreation voluntary associations. Leisure Sciences 36(1): 68-87.

Lum, C. S., S. J. Keith, and D. Scott. 2020. The long-distance hiking social world along the Pacific Crest Trail. Journal of Leisure Research 51(2): 165-182.

Maas, J., S. M. E. Van Dillen, R. A. Verheij, and P. P. Groenewegen. 2009. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health: a multilevel analysis. Health & Place 15: 586e592.

Martin, S. 2017. Real and Potential Influences of Information Technology on Outdoor Recreation and Wilderness Experiences and Management. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 35(1): 98-101.

Mills, A. S. and T. S. Butler. 2005. Flow experience among Appalachian Trail thru hikers.

Proceedings of the 2005 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium. 366-370.

National Trail System Act [NTSA] 2009. Retrieved on April 30, 2020, from https://www.nps.gov/nts/legislation.html.

Pacific Northwest Trail Association [PNTA]. 2020. Retrieved on April 30, 2020, from https://www.pnt.org.

Peters, K., B. Elands, and A. Buijs. 2010. Social interactions in urban parks: stimulating social cohesion? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 9(2): 93-100.

Peterson, B. A., M. T. Brownlee, and J. L. Marion. 2018. Mapping the relationships between trail conditions and experiential elements of long-distance hiking. Landscape and Urban Planning 180: 60-75.

Ptasznik, A. 2015. Thru-hiking as Pilgrimage: Transformation, Nature, and Religion in

Contemporary American Hiking Novels.(unpublished master’s thesis). University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado.

Rush, L. S. 2002. Multiliteracies and design: Multimodiality in the Appalachian Trail thru hiking community. (unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia.).

Robertson, M. and S. Goetz. 2017. Lived experiences of 1996 Appalachian Trail thru-hikers. Journal of Unconventional Parks, Tourism & Recreation Research 7(1): 16-21.

Robinson, R. A. 2013. Described experiences of long-distance thru-hiking: A Qualitative content analysis (unpublished doctoral dissertation). Capella University, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Ryan, R. M. and E. L. Deci. 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist 55(1): 68-78.

Seidman, I. 2006. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences. New York: Teachers College Press.

Sibthorp, J., N. Furman, K. Paisley, J. Gookin, and S. Schumann. 2011. Mechanisms of learning transfer in adventure education: Qualitative results from the NOLS transfer survey. Journal of Experiential Education 34(2): 109-126.

Stewart, W. P. 1998. Leisure as multiphase experiences: Challenging traditions. Journal of Leisure Research 30(4): 391-400.

Thapa, B. 2010. The mediation effect of outdoor recreation participation on environmental attitude-behavior correspondence. The Journal of Environmental Education 41(3): 133-150.

Tsaur, S. H. and Y. W. Liang. 2008. Serious leisure and recreation specialization. Leisure Sciences 30(4): 325-341.

Turley, B. 2011. Assessment of readjusting to life after completing a thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail. (unpublished senior project). California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, California.

Whiting, J. W., L. R. Larson, G. T. Green, and C. Kralowec. 2017. Outdoor recreation motivation and site preferences across diverse racial/ethnic groups: A case study of Georgia state parks. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 18: 10-21.

Xiang, Z., D. Wang, J. T. O’Leary, and D. R. Fesenmaier. 2015. Adapting to the internet: Trends in travelers’ use of the web for trip planning. Journal of Travel Research 54(4): 511-527.

Zajchowski, C. A., K. A. Schwab, and D. L. Dustin. 2017. The experiencing self and the remembering self: Implications for leisure science. Leisure Sciences 39(6): 561-568.

Zealand, C. 2007. Decolonizing experiences: an ecophenomenological investigation of the lived-experience of Appalachian Trail thru-hikers. (unpublished master’s thesis). University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario.

Ziegler, M. F., T. Paulus, and M. Woodside. 2014. Understanding informal group learning in online communities through discourse analysis. Adult Education Quarterly 64(1): 60-78.

Read Next

Foundation and Future of Long Distance Trails

We begin this special edition of the International Journal of Wilderness with references to the U.S. Wilderness and National Trails System Acts to illustrate the significance and interconnectedness of wilderness areas and long-distance trails.

With Collaboration We Can Overcome Challenges Together

The concepts of “shared stewardship” or “collaborative management” can be challenging. They require shared vision, definition of clear roles and responsibilities, and commitment to the collaborative process.

Shared Stewardship and National Scenic Trails: Building on a Legacy of Partnerships

National Scenic Trails connect people with the natural and cultural heritage of the United States. Theses trails also provide important opportunities for agencies to engage partners in trail stewardship and sponsorship.