Science & Research

BY RAMESH GHIMIRE, GARY T. GREEN, H. KEN CORDELL, ALAN WATSON, and CHAD P. DAWSON

April 2015 | Volume 21, Number 1

Introduction

In 1995, directors of the four federal land management agencies (Forest Service, National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Fish and Wildlife Service) charged with managing the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS) signed an Interagency Wilderness Strategic Plan (Bureau of Land Management et al. 1995). That plan has guided stewardship and management of the NWPS over the last 20 years. However, since that signing, much has changed in the United States, such as diminishing natural landscapes, more invasive plant and animal species, and a rapid change in global climate. The agencies decided it was time to revisit the 1995 strategic plan and to update the NWPS management goals and objectives.

Updating goals and objectives for the next 20 years requires identifying both today’s and tomorrow’s stewardship issues. The year 2014 marked the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act and presented an opportunity to refocus stewardship and science on the most relevant and pressing issues now and in the future. In support of NWPS planning, a Wilderness Manager Survey (WMS) was developed and administered to managers in all four federal agencies that manage the NWPS. The emphasis of the survey was to have managers think about the threats, the research and training needs, and the most pressing challenges facing wilderness stewardship over the next 20 years.

Survey Methods

The WMS was administered online and included job characteristics of the responding managers, science information needed for stewardship, and education and training needs for staff. Descriptive questions asked about management duties, tenure in wilderness management, years with their agency, and name of state and the wilderness area(s) where respondents spent the most of their work time (both office and on-site). A series of open-ended and ordinal-level categorical questions were asked about threats to the NWPS, major stewardship and management challenges, training needs for staff, research needs for decision making, and the two most important problems likely to face managers in the future. The listed categorical questions asked managers to rate the level of threat or challenge to stewardship and level of need for training and research. Separate modules at the end of the survey were completed at the discretion of the respondent on: (1) the importance of 13 listed wilderness values (Cordell et al. 2008) on a five-point scale, from not at all important to extremely important; and (2) level of accomplishment of the 1995 Interagency Wilderness Strategic Plan (Bureau of Land Management et al. 1995).

The survey instrument was developed by a team of seven scientists and went through many rounds of team reviews and revisions. Both the instrument and its administration through SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com) were pilot-tested by a panel of 17 retired wilderness managers who had worked at a variety of levels in one or more of the managing agencies. They took the survey, indicated time to complete it, commented on design improvements, and indicated their opinions on contents such as most significant issues.

Survey administration of the final revised WMS included the entire NWPS; however, implementation was hampered by not knowing the actual number of wilderness managers (survey population) or having up-to-date identification of specific employees assigned wilderness management duties. Requests to NWPS managers to participate in the survey were sent to field, regional, and national offices by a national representative of each agency. Wilderness management was broadly defined to include law enforcement, public information, resource and visitor management, planning, and policy.

Completed surveys were forwarded by SurveyMonkey to team members at the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia, for analysis. Data were analyzed and reported by the USDA Forest Service and University of Georgia team members to both the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute and the Arthur Carhart Wilderness Training Center in Missoula, Montana (Ghimire et al. 2014). The staff at the institute and center were charged with developing drafts of the 2020 Vision documents to guide management of the NWPS for the next 20 years (Bureau of Land Management et al. 2014).

National Wilderness Manager Survey Results

Responses to the main survey were received from 368 managers of the NWPS between February 24 and May 19, 2014. In addition, 156 respondents completed the perceived accomplishment of the 1995 Interagency Wilderness Strategic Plan objectives module, and 157 respondents completed the Wilderness Values module.

Accomplishment of 1995 NWPS Strategic Plan Goals and Objectives

Managers were asked to evaluate the degree to which they believed the five goals and objectives of the 1995 Interagency Wilderness Strategic Plan had been accomplished between 1995 and 2014 by their agencies. Managers responded using a scale from no achievement to very high achievement. Managers indicated a slight to moderate accomplishment of these goals and objectives. As one approach for evaluating accomplishments, we focus herein on percentages of respondents indicating no to only slight accomplishment. There is significant variation in scoring among the four agencies.

1. Preservation of Natural and Biological Values – Restoring fire to its natural role in the ecosystem, inventory and monitoring wilderness ecosystems and establishing long-term research, restoring wilderness ecosystems damaged by humans, identifying the processes needed to mitigate human-induced change, implementing exotics management, and retiring uses adversely affecting wilderness values were the top five objectives in this category rated as underachieved.

2. Management of Social Values – Minimizing low-level overflights, assessing and mitigating impacts of emerging technologies, coordinating with neighboring agencies on use restrictions, evolving and using recreation management tools, and minimizing the impact of structures are the top objectives in this category rated as underachieved.

3. Administrative Policy and Interagency Coordination – The top five underachieved administrative and policy objectives as rated by managers include participation in local government planning, fiscal accountability, seeking new partnerships, expanding research, and ensuring flexible spending of fire funding.

4. Training of Agency Personnel – Integrating wilderness manager and employee orientation training, expanding university partnerships, and developing a common understanding of wilderness management principles were the top three objectives seen by managers as underachieved.

5. Public Awareness and Understanding – The top three public awareness objectives evaluated by managers as underachieved were wilderness education, communication with diverse social groups, and a wilderness curriculum for K–12.

It appears that more work will be needed toward achievement of a number of the 1995 NWPS objectives. In particular, these include the areas of research, partnerships, education, communications, ecosystem protection, leadership, interagency coordination, professional development, and control of inconsistent uses and access.

Profiles, Values, Threats, and Challenges

On average, respondent managers had worked about 12 years with some type of wilderness management assignment. However, this varies across agencies. For instance, the percentage of the Forest Service managers with five or fewer years working in wilderness was much smaller than that of managers of the other agencies. The Fish and Wildlife Service had the largest percentage of respondents with five or fewer years of wilderness assignment.

Respondents worked at different management levels in their respective agencies. The majority of the respondents in the Bureau of Land Management, as well as from the other agencies were from field offices. The number of survey respondents varied across states with the largest percentage of respondents (17%) from California, followed by Arizona (8%), Alaska and Oregon (7%), Colorado and Montana (6%), Florida and New Mexico (5%), and Idaho, Nevada, and Utah (each with 4%).

Managers were asked to rate the importance of 13 values for wilderness. The five values most often reported as very or extremely important by respondent managers were: (1) knowing that future generations will have wilderness (97%), followed by (2) preserving unique wild plants and animals (94%), (3) protecting water quality (85%), (4) protecting wildlife habitat (84%), and (5) protecting rare and endangered species (79%).

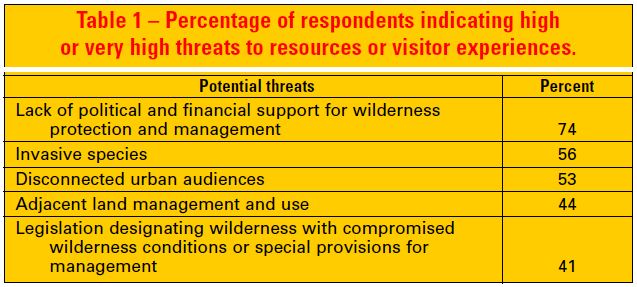

Managers were presented with a list of 24 potential threats most likely to affect wilderness character, specific resources, or visitor experiences over the next 20 years. Respondents were provided a five-point scale (none to very high potential threat) and a “not sure” option to rate the level of potential threat over the next 20 years at the wilderness area or areas in which they work. The top five that pose a high or very high threat are summarized in Table 1. Nearly three out of four managers reported that lack of political and financial support for wilderness protection and management was a serious threat to wilderness stewardship.

Table 1 – Percentage of respondents indicating high or very high threats to resources or visitor experiences.

Table 2 – Percentage of respondents indicating major challenges in wilderness stewardship or planning in next 20 years.

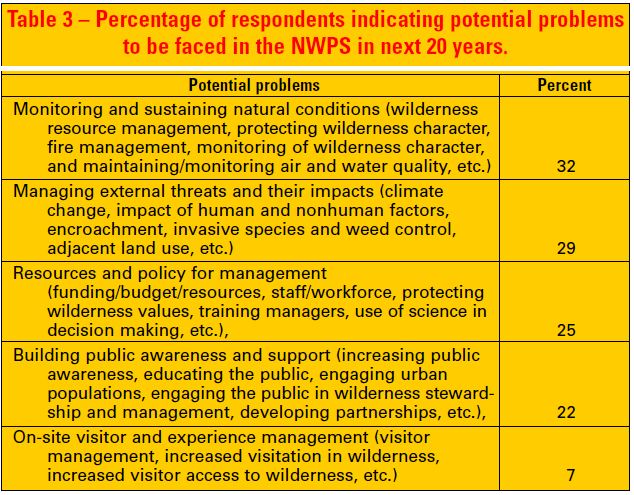

Table 3 – Percentage of respondents indicating potential problems to be faced in the NWPS in next 20 years.

Managers were asked to indicate up to five major challenges they or their successors will likely face over the next 20 years in wilderness stewardship or planning. The challenges identified by managers fall into six broad categories (Table 2). Management of external threats was listed most frequently as the major challenge, followed by resources and policy to support management.

As an open-ended question, managers were asked to describe the two most important problems that will need to be collectively addressed in the coming 20 years to steward and manage wilderness areas. The most important problems as identified by the managers fall into five broad categories (Table 3), with monitoring and sustaining natural conditions (wilderness resource management, protecting wilderness character, fire management, monitoring of wilderness character, and maintaining/ monitoring air and water quality, etc.) identified by managers as the most significant problem that need to be addressed in the coming 20 years.

Training and Research Needs

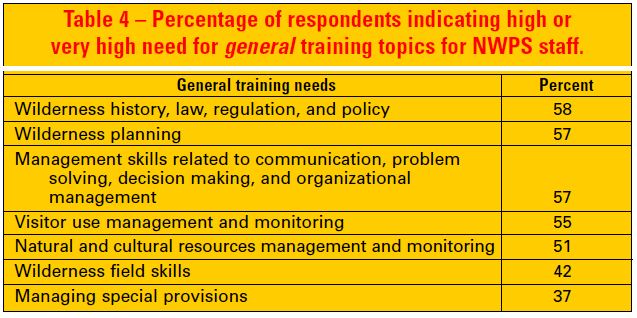

Managers were asked to indicate the level of need for general training during the next 20 years for building greater competencies within their agency. They were provided seven different general training topics and asked to evaluate (using a five-point scale) the level of need for training in each of these topics. The most often reported topic of high or very high need for training was identified as wilderness history, law, regulation, and policy (Table 4).

Table 4 – Percentage of respondents indicating high or very high need for general training topics for NWPS staff.

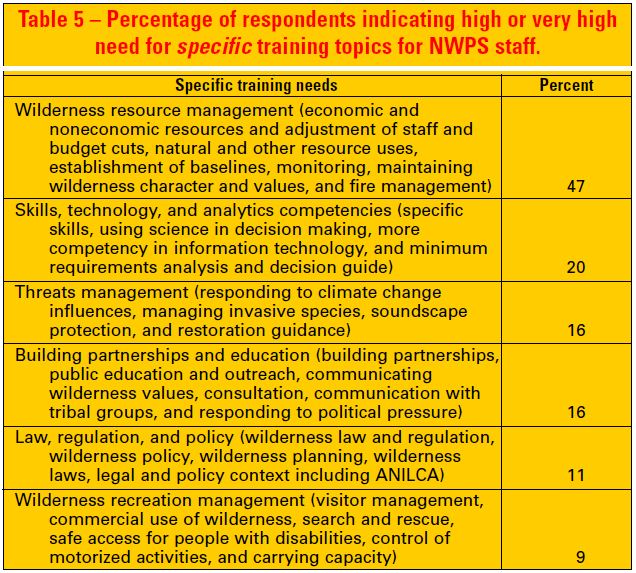

The WMS asked managers to indicate their top five specific training needs. The responses were categorized into six groups to better understand the specific training needs reported by managers. The top category of specific training needs identified by the managers was wilderness resource management (economic and non-economic resources and adjustment of staff and budget cuts, natural and other resource uses, establishment of baselines, monitoring, maintaining wilderness character and values, and fire management) and followed by five other categories of specific training needs (Table 5).

Table 5 – Percentage of respondents indicating high or very high need for specific training topics for NWPS staff.

Responding managers were presented with 19 different aspects of wilderness management and planning and asked to indicate how adequate and available science-based information was for each of those aspects. The five aspects with the highest percentage of managers rating them inadequate or somewhat adequate (thus indicating a need for research in those areas) included public attitudes toward intervention to adapt to climate change influences, public attitudes toward ecological restoration activities (involving fire, vegetation, and wildlife), relative value of wilderness benefits to stakeholder groups, stewardship of spiritual values and uses, and approaches for better management of field staff (Table 6).

Table 6 – Percentages of managers indicating science-based information not adequate or only somewhat adequate for managing the NWPS.

Respondent managers were asked to identify their top five specific research needs for resource and visitor management in wilderness areas. The top research needs for resource and visitor management, as identified by managers, are categorized into four subject areas in Table 7. The top research information need was categorized as threats and impacts management (impact on wilderness resources and on opportunities for solitude due to human and natural factors, invasive species, climate change impact on wilderness character, monitoring/preserving soundscapes, ecosystem integrity, and nearby land uses).

Table 7 – Percentages of managers indicating specific research information needs for managing the NWPS.

Discussion

The emphasis of the survey was to have managers think about the threats, research and training needs, and most pressing challenges facing wilderness stewardship over the next 20 years. The intent was to reflect on what had been accomplished since 1995 on the Interagency Wilderness Strategic Plan (Bureau of Land Management et al. 1995) and to look forward to what was needed over the next 20 years for stewardship and management of the NWPS. One additional outcome was to provide some input to the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute and the Arthur Carhart Wilderness Training Center as they developed drafts of the 2020 Vision documents to guide management of the NWPS for the next 20 years (Bureau of Land Management et al. 2014).

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank our other two science team members, Rudy Schuster, scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey, and Troy Hall, professor at Oregon State University, as well as Alexandra Fulmer, graduate student in Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, for her help in qualitative data analysis.

References

Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and U.S. Forest Service. 1995. Interagency Wilderness Strategic Plan 1995. Retrieved November 15, 2014, from http://wilderness.nps.gov/document/I-21.pdf.

Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service, and U.S. Geological Survey. 2014. 2020 Vision: Interagency Stewardship Priorities for America’s National Wilderness Preservation System. Retrieved November 15, 2014, from www.wilderness.net/toolboxes/documents/50th/2020_Vision.pdf.

Cordell, H. Ken, Carter J. Betz, J. Mark Fly, Shela Mou, and Gary T. Green. 2008. How do Americans view wilderness. Retrieved November 15, 2014, from http://warnell.forestry.uga.edu/nrrt/nsre/IRISWild/IrisWild1rptR.pdf.

Ghimire, R., H. K. Cordell, G. T. Green, and S. Mou. 2014. National Wilderness Manager Survey 2014. Report submitted to Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute and Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center, Missoula, MT.

RAMESH GHIMIRE is a post-doctoral research associate at the University of Georgia, Athens, GA; email: ghimire@uga.edu.

GARY T. GREEN is an associate professor at the University of Georgia, Athens, GA; email: gtgreen@uga.edu.

H. KEN CORDELL is a scientist emeritus at the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute and the Southern Research Station, Athens, GA; email: kencordell@gmail.com.

ALAN WATSON is a social scientist with the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, USDA Forest Service, Missoula, MT; email: awatson@fs.fed.us.

CHAD P. DAWSON is a professor emeritus at the College of Environmental Science and Forestry, State University of New York, Syracuse, NY; IJW editor-in-chief; and board member for the Society of Wilderness Stewardship; email: chad@wild.org.