Military Aircraft Wilderness Overflights: Mitigating Their Impact

Stewardship

April 2018 | Volume 24, Number 1

Military aircraft overflights of wilderness areas is a complicated issue with no easy answers. Overflights can cause negative impacts to wilderness areas and users, however the military has a requirement to maintain aviation readiness. While the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has given a recommendation for civilian aircraft to fly at least 2,000 ft. above National Parks, Wildlife Refuges, and Wilderness/Primitive areas, there is no such official Department of Defense (DoD) wide recommendation or ruling that exists for military aircraft (USDOT 2014). Additionally, recent legislation designating many wilderness areas throughout the Western U.S. have included a special provision specifically allowing low altitude military flights, and the four wilderness management agencies have no authority over the airspace above protected areas (Gorte 2011). This paper will examine law, DoD regulations, and agency policies pertaining to military overflights in wilderness, as well as the impacts of low-level flights. It will also examine how coordination between the DoD and wilderness land management agencies can help mitigate overflight impacts and suggest further steps that are needed.

Laws and Regulations Addressing Military Overflights

Although dealing with military overflights of wilderness areas remains challenging and complex, there are a surprising amount of laws and regulations that deal with this issue. While aircraft overflights of wilderness are not addressed in the Wilderness Act, the Act does provide a baseline for management that is applicable to this subject. Section 2(a) discusses the intent of wilderness areas: “administered for the use and enjoyment of the American people…to provide for the protection of these areas, the preservation of their wilderness character” (U.S. Public Law 88-577). Section 4(b) then describes administrative responsibility: “each agency administering any area designated as wilderness shall be responsible for preserving the wilderness character of the area” (U.S. Public Law 88-577). The overarching goal of wilderness management is to protect and preserve wilderness character, and just as non-conforming but allowed uses such as grazing should be closely monitored to be minimally impactful, so should military aircraft overflights.

Subsequent legislation has made it clear that wilderness designation will not restrict this practice. The Nevada Wilderness Protection Act of 1989 was the first to address this issue by stating: “Nothing in this Act shall preclude low level overflights of military aircraft, the designation of new units of special airspace, or the use or establishment of military training routes over [named] Wilderness areas” (U.S. Public Law 101-195, p. 6). The Arizona Desert Wilderness Act of 1990 used similar language a year later. This special provision was then expanded even further with the California Desert Protection Act of 1994: “Nothing in this Act, the Wilderness Act, or other land management laws…shall restrict or preclude low-level overflights of military aircraft over such units, including military overflights that can be seen or heard within such units” (U.S. Public Law 103-433, p. 31). The California Desert Protection Act is also noteworthy because it concludes that “continuation of these military activities under appropriate terms and conditions [emphasis added], is not incompatible with the protection and proper management…” (U.S. Public Law 103-433). Many wilderness managers and users would disagree with this statement and would instead argue that military overflights are actually incompatible with the preservation of wilderness characteristics because of the potential disruption they can cause to both users and wildlife. However, the terminology “appropriate terms and conditions” implies that military and land management agencies should be working cooperatively to facilitate both proper training opportunities as well as preservation of protected areas.

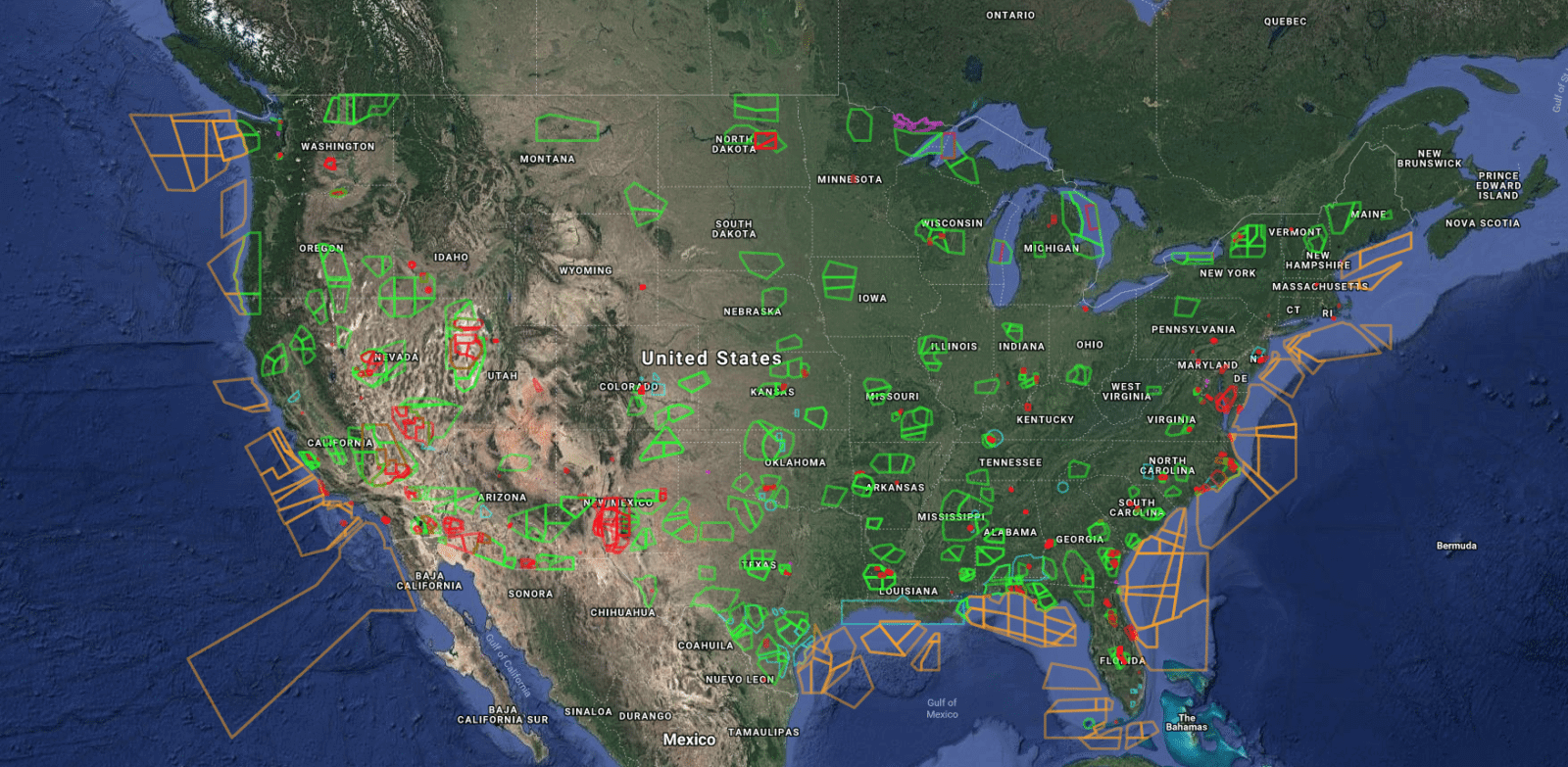

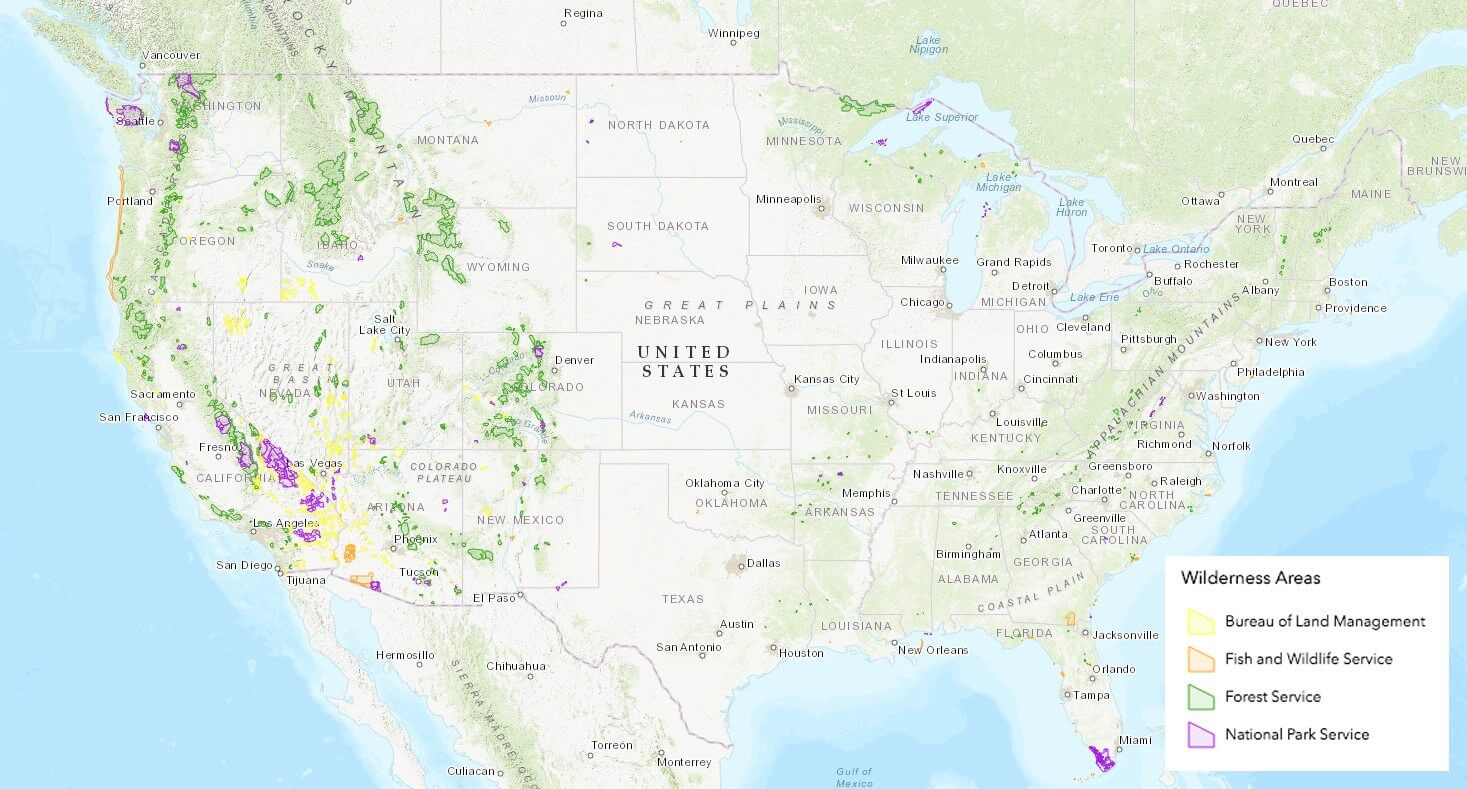

Using special provision language to specifically allow for military overflights continued in eight more wilderness statutes centered primarily on areas in Nevada, southern California, Arizona, Idaho, and Utah (Gorte 2011). However, many other wilderness bills passed during this time did not include this provision. This inconsistency suggests that military overflights are not a universal issue in designated wilderness areas, but instead are primarily site-specific and existing where military overflights were a prior use (University of Colorado Boulder, 2004a). Most of these areas are in the Western United States where a great deal of flight training and testing is conducted. Figure 1 depicts the Military Operations Areas (MOAs) or airspace that the United States Air Force (USAF) uses. The colored boxes are designated airspace blocks with the green boxes being those that are most often used for training. Figure 2 depicts wilderness area locations. Most of the largest green airspace blocks from Figure 1 are in the Western United States in the same regions that have most wilderness areas. Understandably, these regions were those with legislation that included the special provision language for military overflights, and these are the regions in which wilderness management will most likely encounter disturbances from military overflights.

One final piece of legislation that has been highly influential in addressing military overflights of wilderness is The National Parks Overflights Act of 1987 (U.S. Public Law 100-91). This law directed the National Park Service (NPS) and US Forest Service (USFS) to conduct studies of wilderness areas under their management to determine the impacts of aircraft overflights (both military and civilian) on wilderness users and resources. The resulting reports thoroughly outline the nature of impacts resulting from aircraft overflights and some suggested measures for mitigating these impacts.

DoD Regulations

The U.S. Air Force (USAF) and U.S. Navy (USN) are the most active and prolific users of jet propulsion aircraft in the DoD. The USN has dealt with aircraft overflights in much the same manner as the FAA by simply issuing a minimum altitude for aircraft, although in this case the altitude is mandatory. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OpNav) Instruction 3770.2K has a specific section on noise sensitive areas which states: “noise sensitive areas (e.g., wilderness areas, wildlife refuges) shall be avoided to the maximum extent possible; this applies for altitudes less than 3,000 feet AGL” (US DoD 2007). Going below this 3,000-ft. threshold requires specific approval, and aircraft are permitted to fly over these kinds of areas when above 3,000 ft. While not eliminating overflights completely, this instruction succinctly provides a reasonable compromise.

The USAF has several Air Force Instructions (AFIs) addressing the subject. Although overflights of protected areas are not specifically included, AFI13-201 outlines the importance of national and regional Airspace and Range Council meetings that provide for a dialogue between the DoD and other organizations such as the NPS, BLM, USFWS, and USFS (US DoD 2013). These meetings provide the optimum forum for wilderness management agencies to discuss airspace management issues or concerns such as overflight impacts. One notable result of these gatherings has been the creation of The USAF and NPS Western Pacific Regional Handbook which is a reference guide designed to improve communication between the two agencies. 9 (US DoD & NPS 2002). In it not only are foundational operating procedures covered for both agencies, but explicit instructions are also given for how to reach out to coordinate with each other.

Besides guidance given in the above operating instructions, a method of measuring natural resources impacts has been developed for the DoD called the Military Ecological Risk Assessment Framework (MERAF). It is based on the EPA’s ecological risk assessment framework and is modified to be more useful to the training and testing organizations within the DoD (which encompasses many flying units) (Suter et al., 2002). An offshoot of this framework was developed specifically to address military overflights, and it is called the Ecological Risk Assessment Framework for Low-Altitude Overflights by Fixed-Wing and Rotary-Wing Military Aircraft. Conducting an environmental assessment is required by NEPA before activities such as flying training or testing operations, and using this framework fulfills that requirement.

Wilderness Management Agency Policies

USFS direction in Chapter 2320 – Wilderness Management of the USFS Manual is to discourage flights over wilderness that are below 2,000 ft. except for emergencies or essential military missions. What qualifies a military mission as essential is not provided, however the USFS does advocate cooperating with the FAA, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and military authorities to ensure compliance with this altitude suggestion (USDA Forest Service 2007). The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) gives almost identical guidance in the Management of Designated Wilderness Areas section of the BLM Manual. Low flights are to be discouraged except in the cases of emergencies, essential military missions, or wildlife operations. Again, cooperation with military authorities, FAA, state agencies, and pilots in the general area is encouraged if low overflights are a problem (USDI BLM, 2012). The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) policy is much the same in its direction, and like the FS and BLM, the standard FAA minimum altitude of 2,000 ft. is promoted. Military aircraft are not specifically mentioned; however, the USFWS does make a specific point to instruct wilderness administrators to “monitor and document low-level aircraft activity” (USDI FWS 2008).

In contrast, the NPS has the most abundant and clear guidance on overflights, with a specific section of their NPS Management Policies devoted to military aviation. While the other agencies advocate cooperation in general terms, the NPS specifically states: “Superintendents are responsible for opening lines of communication with base commanders controlling military training routes or military operations areas that may affect their parks, and for developing formal agreements that mitigate identified impacts” (USDI NPS 2006 p. 110). This is significant because it gives park management a clear starting point and pinpoints who exactly is responsible for this coordination. In addition, the USAF and NPS Western Pacific Regional Handbook provides thorough guidance on how to handle the issue of military overflights. Understanding the directives and legislation guiding the practice of military overflights of wilderness areas is vital in minimizing impacts. However, an equally essential step is to analyze precisely what kind of impacts overflights can cause.

Impacts of Military Overflights of Wilderness

Multiple studies have been conducted to analyze the threat that military overflights pose to preservation of wilderness areas. The types of impacts resulting from military overflights can generally be broken down into two categories: noise and visual disturbance to wilderness users and noise disturbance to wildlife. Both categories relate to the concept of natural quiet – a wilderness resource just like clean air or water, and as such, in need of protection. The decline of natural quiet contributes to sound disturbances to visitors and wildlife, and both seem to be becoming more accustomed to disturbances. However, the fact that visitors and wildlife may be more accustomed to noise interference should not be a reason to ignore preserving natural quiet.

Noise and Visual Disturbance

Measuring noise and sight disturbance to wilderness visitors is quite complex due to the many variables that contribute to whether a visitor feels disturbed. Many visitors go to wilderness to have a recreational experience in a natural setting away from the sights and sounds of civilization, and often an aircraft overflight is going to intrude on that experience. While studies have shown that the sound and sight of aircraft overflights do act as a disturbing factor for wilderness visitors, the percentage of visitors who rated this disturbance as only slightly annoying was much greater (averaging at about 85%) compared to visitors who rated aircraft disturbance as moderately, very, or extremely annoying (USDA Forest Service 1992). This study additionally found that about 65% of visitors rated aircraft as having no effect on their visit, and about 92% of visitors intended to visit the same wilderness areas in the future.

Noise Disturbance to Wildlife

Impacts to wildlife can include but are not limited to: physiological responses, behavioral responses, indirect effects such as energy loss, and accidental injury (USDI NPS 1995). Overflights can cause a physiological response in wildlife such as increased heart rates; however, there is not much understanding or consensus on whether this is harmful (USDI NPS 1995). Behavioral responses vary wildly depending on species, age, sex, etc., with some species showing massive responses while others show no response. Some observed responses to aircraft overflights include interference in feeding and nesting of some bird species potentially leading to abandonment of the area, energy losses, and possible reproductive losses (Dewey & Mead 1994). There have also been management perceptions of raised stress levels in some mammals which combined with environmental stressors such as winter or fawning season, could potentially cause mortality (Dewey & Mead 1994). Some studies have found that many species seem to habituate to the noise intrusion over time (Larkin et al., 1996). This information shows that there is somewhat of a lack of agreement on how significant overflight impacts really are. Nevertheless, it is still important to mitigate any impacts as much as possible.

Just Fly Higher?

Often the assumption is that simply moving aircraft to a higher altitude will be enough to remove the adverse effects of aircraft overflights. However, in a 1992 report to Congress the FS found that unless aircraft are flying very low (1,000 ft. or below), increasing altitude will not seriously affect the impact of sound to wilderness visitors or resources (USDA Forest Service 1992). This finding can be still important today when trying to mitigate overflight impacts – not flying at very low altitudes over wilderness will help, but complete avoidance of these areas is ideal.

Cooperation to Mitigate Impacts

In a 2004 Management Survey conducted by the University of Colorado School of Law looking at special uses in 60 wilderness areas located in the Western United States, it was found that military overflights occurred over 34% of the areas surveyed. 47% of these flights occurred monthly or more frequently, and 43% occurred only several times a year (University of Colorado Boulder 2004b). The areas with the highest rates of overflights were those located in the Great Basin and Mojave/Sonoran/Chihuahuan areas which correlates with areas in which wilderness designation legislation was passed that included a special provision for military overflights. Ten years later, the 2014 Wilderness Managers Survey Report found that minimizing low-level overflights remains one of the top five underachieved objectives for managers in all four wilderness management agencies. When asked does your agency “Coordinate with DoD agencies and the FAA to develop procedures and guidelines to avoid or mitigate low-level overflights,” 55% of managers responded, “not at all or only slight accomplishment” and only 13% responded “high or very high accomplishment” (Ghimire et al. 2015). Wilderness agencies should know whether the wilderness areas under their jurisdiction have military overflights as a pre-existing use or will encounter the issue of military overflights. Yet 55% of managers in this survey have not effectively dealt with military overflights. Where is the breakdown occurring?

Implementing Coordination Resources

With many extensive and thorough coordination efforts and resources available, one would think that efforts to mitigate overflight impacts would be more effective. The problem may simply be that wilderness managers do not know where to start, where to find information, or who to coordinate with to mitigate military overflights. Guidelines and operating procedures lay the groundwork for great cooperation, but more guidance like the USAF and NPS Western Pacific Regional Sourcebook that facilitates cooperation may be needed. Additional needs may include:

- Holding pilots more accountable for maintaining area/altitude restrictions

- Better effort by flying squadrons to assess environmental impacts and involve outside agencies in training planning

- Greater effort by land management agencies to reach out to DoD when problems arise

- More diligent completion of tools like the Ecological Risk Assessment Framework

- Increased public involvement and notification in decisions about airspace actions and proposals

- The bottom line is that to be successful, both sides of this issue must actively involve each other.

A Successful Example of Active Cooperation

A perfect example of active cooperation can be seen in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (SKCNPs) near the R-2508 Military Aviation Training Complex. Conflict has existed in this area since jet aircraft began operating there in the 1950s. To help overcome these challenges, NPS managers started a wilderness pack trip in 1996 to facilitate communication and understanding between the military and NPS. Later, NPS managers started being invited to contribute to R-2508 planning, and both parties developed a cooperative system of determining when pilots flew below the 3,000-foot (914 m) mandatory minimum altitude that the military instituted (Fauth 2009). SKCNPs also contributed to the USAF and NPS Western Pacific Regional Sourcebook. The outcome of this continuous communication and cooperation is better education and understanding by both the NPS and the military as well as the achievement of each organization’s goals (Fauth 2009).

Conclusion

Despite bureaucratic and legislative challenges, there has been incredible progress towards cooperation that can help mitigate overflight impacts. Managers need to take this foundation and build upon it to facilitate communication and cooperation in their individual wilderness areas. The goals of the military and NWPS do not need to be locked in a constant state of conflict. There is proof that simply reaching out to understand each other can result in the kind of partnership needed to achieve both agencies’ missions.

CHRISTINA CARLTON is a captain in the United States Air Force and works as an intelligence officer supporting Tactical Air Control Party; email: christina.carlton.1@us.af.mil

References

Dewey, R., and D. Mead. (994. Unfriendly Skies: The Threat of Military Overflights to National Wildlife Refuges. Defenders of Wildlife. Retrieved October 12, 2016 from: file:///C:/Users/miste_000/Downloads/DefendersWild_Unfriendly_Skies,_Threat_of_Military_Overflight_to_NWRs,Jan_1994_073.pdf

Fauth, G. 2009. Military Overflight Management and Education Program – Immersion and Communication. George Wright Society Rethinking Protected Areas in a Changing World Conference Proceedings. Retrieved September 16, 2016 from: http://www.georgewright.org/0905fauth.pdf

Ghimire, R., K. Cordell, A. Watson, C. Dawson, and G. Green. 2015. Results from the 2014 National Wilderness Manager Survey. Gen. Tech Rep RMRS-GTR-336. USDA, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO.

Gorte, R. 2011. Wilderness Laws: Statutory Provisions and Prohibited and Permitted Uses. Rep. R41649. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved September 14, 2016 from: http://www.wilderness.net/NWPS/documents/Wilderness%20Laws-Statutory%20Provisions%20and%20Prohibited%20and%20Permitted%20Uses.pdf

Hawg-View. n.d. Map depicting United States Air Force Military Operations Areas (MOAs). Retrieved October 12, 2016 from: http://www.hawg-view.com/

Larkin, R., L. Pater, and D. Tazik. 1996. Effects of Military Noise on Wildlife: A Literature Review. U.S. Army Construction Engineering Research Laboratories (USACERL) TR- 96/21. Retrieved September 20, 2016 from: http://oai.dtic.mil/oai/oai?verb=getRecord&metadataPrefix=html&identifier=ADA305234

Suter, G., K. Reinbold, W. Rose, and M. Chawla. 2002. Military Ecological Risk Assessment Framework (MERAF) For Assessment of Risks of Military Training and Testing to Natural Resources. Environmental Sciences Division Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Retrieved September 16, 2016 from: http://www.esd.ornl.gov/programs/ecorisk/documents/MERAF_final.pdf

University of Colorado Boulder. 2004a. Special Use Provisions in Wilderness Legislation. Natural Resources Law Center. Retrieved September 14, 2016 from: http://www.wilderness.net/toolboxes/documents/MSP/Spec.%20Use%20Provisions%20in%20Legislation.pdf

University of Colorado Boulder. 2004b. Special Uses in Wilderness Areas: Management Survey. Natural Resources Law Center. Retrieved September 14, 2016 from: http://www.wilderness.net/toolboxes/documents/MSP/Spec.%20Uses%20Survey.pdf

US Department of Defense (US DoD), Air Force. 2013. Air Force Instruction 13-201 Airspace Management. Air Education and Training Command Supplement, Space, Missile, Command and Control. Retrieved October 14, 2016 from: http://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/aetc/publication/afi13-201_aetcsup_i/afi13-201_aetcsup_i.pdf

US Department of Defense (US DoD), Navy. 2007. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OpNav) Instruction 3770.2K Airspace Procedures and Planning Manual. Chief of Naval Operations. Retrieved October 14, 2016 from: https://doni.documentservices.dla.mil/Directives/03000%20Naval%20Operations%20and%20Readiness/03-700%20Flight%20and%20Air%20Space%20Support%20Services/3770.2K.pdf

US Department of Defense (US DoD), Air Force & USDI, National Park Service. 2002. Western Pacific Regional Sourcebook. Retrieved September 18, 2016 from: http://www.nature.nps.gov/naturalsounds/PDF_docs/USAFNPSWesternPacificRegionalSourcebook.htm

USDA, Forest Service. 1992. Report to Congress: Potential Impacts of Aircraft Overflights of National Forest System Wildernesses. Retrieved September 22, 2016 from: http://www.fs.fed.us/eng/pubs/pdfimage/92231208.pdf

USDA, Forest Service. 2007. Forest Service Manual 2300 – Recreation, Wilderness, and Related Resource Management Chapter 2320 – Wilderness Management. Retrieved October 12, 2016 from: http://www.fs.fed.us/im/directives/dughtml/fsm_2000.html

USDI, Bureau of Land Management. 2012. Management of Designated Wilderness Areas. BLM Manual Section 6340. Retrieved October 12, 2016 from: http://www.blm.gov/wo/st/en/info/regulations/Instruction_Memos_and_Bulletins/blm_manual.html

USDI, National Park Service. 1995. Report to Congress: Report on Effects of Aircraft Overflights on the National Park System. Retrieved September 20, 2016 from: http://www.nonoise.org/library/npreport/intro.htm

USDI, National Park Service. 2006. Management Policies. Retrieved September 20, 2016 from:http://www.nps.gov/policy/mp2006.pdf

USDI, Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Natural and Cultural Resources Management – Wilderness Stewardship. Service Manual, Land Use and Management Series 610. Retrieved October 12, 2016 from: https://www.fws.gov/policy/manuals/part.cfm?series=600&seriestitle=LAND%20USE%20AND%20MANAGEMENT%20SERIES

US Department of Transportation (USDOT), Federal Aviation Administration. 2014. Aeronautical Information Manual: Official Guide to Basic Flight Information and ATC Procedures. Retrieved September 23, 2016 from: https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/media/aim_basic_4-03-14.pdf

U.S. Public Law 88-577. Wilderness Act of September 3, 1964. 78 Stat. 890.

U.S. Public Law 100-91. National Park Overflights Act of 1987, 16 USC §1a-1 note

U.S. Public Law 101-195. Nevada Wilderness Protection Act of 1989, 103 STAT. 1785

U.S. Public Law 103-433. California Desert Protection Act of 1994, 16 USC §410aaa-410aaa-83

Read Next

Examining Satisfaction and Crowding in a Remote, Low Use Wilderness Setting: The Wenaha Wild and Scenic River Case Study

The purpose of this case study was to collect data about summer recreational use of the Wenaha WSR to help managers better understand visitor use and attitudes related to use capacity.

Leave No Trace: How It Came to Be

Despite being unable to identify the precise origin of Leave No Trace, we can identify by whom, when, and how the Leave No Trace message came to be made consistent and coherent and the dissemination of Leave No Trace messages came to be institutionalized.

CoalitionWILD

A generation of new ambition is staring at their future and are grappling with what to do next and where to start.