Leave No Trace: How It Came to Be

Communication & Education

December 2018 | Volume 24, Number 3

Despite being unable to identify the precise origin of Leave No Trace, we can identify by whom, when, and how the Leave No Trace message came to be made consistent and coherent and the dissemination of Leave No Trace messages came to be institutionalized.

Top image by Bob Dvorak: Leave No Trace practices promote conservation in backcountry settings. Nelson Lakes National Park, New Zealand.

Where did the Leave No Trace program come from? Even in the far past, when population levels were lower, outdoor recreation was less popular, and resultant impacts were less problematic, some people undoubtedly recognized the ecological damage recreation can cause. The effects of trampling on vegetation were noted as early as the 18th century, and concern about recreation impacts on redwoods led to studies as early as the 1920s (Liddle 1997). Some who noticed impact would have recognized the link between impact and their recreational behaviors, altered their behaviors accordingly, and encouraged others to do the same. This awakening awareness was the ultimate origin of the Leave No Trace (LNT) movement.

Backcountry Recreation Booms in the 1960s and 1970s

Unfortunately, awakening awareness and resultant behavioral change were insufficient to offset increasing population and interest in backcountry recreation. By the 1960s, wildland recreation was exploding. Papers were written about wildlands being “loved to death,” about problems with overcrowding and ecological damage, and need for management (e.g., Snyder 1966). Since the problem stemmed from increasing recreational use, the solution most often suggested was to identify a carrying capacity and to limit use so the number of recreationists never exceeded this capacity. In the early 1970s, parks, rivers, and wilderness areas started limiting the number of recreationists through permit systems. Increasingly, they adopted rules and regulations – from limits on group size to designating where camping would and would not be allowed. By the late 1970s, voices began expressing concern that managers were regulating the joy and spontaneity out of wilderness recreation – that education was a better approach to management than regulation (Bradley 1979; Lucas 1982). In hindsight, clearly the question was never one of education as opposed to regulation. Both are necessary and both have been employed since the beginnings of recreation management.

Figure 1 – Burying it in dumps was originally considered the low-impact way to deal with trash in the backcountry. However, as backcountry travel increased in popularity, trash in the backcountry became a huge problem requiring changes in behavior.

By the late 1970s, efforts to educate recreationists about how to minimize the impacts of their use – what came to be called Leave No Trace – were increasingly common. Rangers talked to people they met on patrol about recommended behaviors on the trail and in camp. Messages were posted on trailhead bulletin boards and distributed in brochures and pamphlets – Wilderness Manners, Low Impact Camping, and Without a Trace: The Wilderness Challenge. Articles were written, providing tips about low-impact recreational use (Harlow 1977; Berger 1979). Books about backpacking often included suggestions about how to minimize one’s impact (Petzoldt 1974; Hart 1977; Waterman and Waterman 1979). Educational programs were developed by the land management agencies and other groups, including the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) and Boy Scouts. Outdoor retailers – such as REI and North Face – put out low-impact messages.

Most messages were developed independently, based on the observations and experience of rangers and other concerned individuals. Sometimes messages were inconsistent. Should all fire rings be broken up or should one be left to encourage repeat use? Guidelines were inconsistent. Should you camp 100 feet from lakes or 200 feet? Terminology was inconsistent. Are we talking about minimum impact or low-impact camping, no trace, or leave no trace? Unfortunately it is impossible to credit all the individuals who developed the behavioral suggestions that provide the foundation for the Leave No Trace program. There were many.

The difficulty of precisely identifying the origin of Leave No Trace is not unique. We cannot trace the precise origin of efforts to educate people about the risks of starting wildfires. But we do know that the Smokey Bear campaign began on August 9, 1944, when the Forest Service and the Ad Council agreed that a fictional bear named Smokey would be their symbol for forest fire prevention, and artist Albert Staehle was asked to paint the first poster of Smokey Bear. Similarly, despite being unable to identify the precise origin of Leave No Trace, we can identify by whom, when, and how the Leave No Trace message came to be made consistent and coherent and the dissemination of Leave No Trace messages came to be institutionalized.

Figure 2 – At first, attempts to educate visitors about how to lessen their impact were spread word of mouth. Here, a wilderness ranger talks to backpackers in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, Washington.

Origins of a National Leave No Trace Program

Something like the Leave No Trace program would eventually have developed if it had not developed in the manner in which it did. However, the program we know today can be traced to a particular event – much the way the Smokey Bear program can be traced to August 1944. In the summer of 1985, Jim Ratz – executive director of the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) – invited a small group of Forest Service (FS) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) managers, researchers, and academics to join him and a few NOLS employees on a three-day backpack into the Popo Agie Wilderness, Wyoming. This was shortly after most of these invitees had attended the first wilderness research conference in Fort Collins, Colorado. On that trip, Ratz shared his interest in having NOLS fund wilderness research and partner with the land management agencies, particularly to improve low-impact messaging and share what NOLS called its Conservation Practices. Ratz’s message was enthusiastically received by trip participants amid discussions about the importance of wilderness education and how it was time to move beyond its disparate and uncoordinated state. All agreed it was time to systematize the message and institutionalize the delivery of that message.

Figure 3 – This pamphlet, distributed by the Northern Region of the Forest Service starting in 1972, was another early attempt to educate visitors.

Work began shortly thereafter on developing a more coherent and science-based set of low-impact messages. Funding for this was provided by both NOLS and Forest Service Research to David Cole – at that time a private researcher with Systems for Environmental Management and an affiliate of the Forest Service’s Wilderness Management Research Unit in Missoula. His task was to collect a diverse array of low-impact messages from different agencies and sources around the country. The sources that were collected – close to a hundred – are listed in Cole (1989). These were sorted into a single coherent set of recommendations, after confirming their basis in science and resolving any conflict between recommendations. The first product of this work was a revision, completed in 1986, of the NOLS Conservation Practices – a 10-page booklet with sections on backcountry travel, campsite selection and use, fires and stoves, sanitation, and waste disposal. Recognizing the need to adapt messages to the different environments where NOLS led courses, the next product was a set of regional guidelines, with conservation practices specific to travel in deserts, in areas at high altitude or latitude, on snow and ice, and along coastlines. Both the general practices and the environment-specific practices are reproduced in Cole (1989).

The final product of this initial work, eventually published in 1989, was a reference handbook on 75 practices that could generally be recommended (Cole 1989). Each practice was described, along with sample messages and a discussion of the problem the practice seeks to avoid and the rationale for its use. Other sections discussed the practice’s importance, controversial elements, knowledge needs, how frequently it is recommended, and costs to visitors. Four frequently recommended practices judged to be counterproductive were identified, as were eight practices that are only appropriate in certain situations. Thousands of copies of this handbook were distributed.

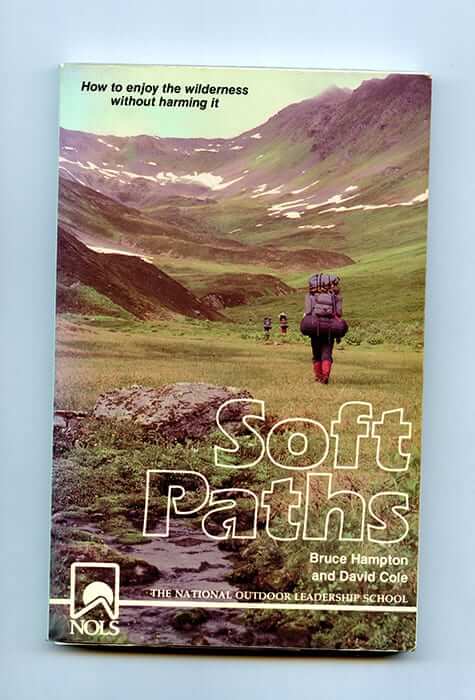

Figure 4 – Soft Paths, the first book-length treatment of Leave No Trace, was one of the early products of cooperation between NOLS and Forest Service Research.

With the wealth of information this effort produced, a logical next step was to develop a book on low-impact practices. Although a few camping and backpacking books included low-impact suggestions (e.g., Hart 1977), no authoritative book-length treatment of the subject had been attempted. Bruce Hampton, an author and former NOLS instructor, convinced Ratz to commission such a book. The book, published in 1988, was entitled Soft Paths, clearly borrowing from the title of John Hart’s Sierra Club guide to backpacking, Walking Softly in the Wilderness. It was subtitled How to Use the Wilderness without Harming It. Like the NOLS Conservation Practices, there was a section on general practices, followed by sections specific to deserts, rivers and lakes, coasts, arctic and alpine tundra, snow and ice, and bear country (Hampton and Cole 1988).

In 1990, NOLS and the Forest Service began work on a video version of Soft Paths. NOLS hired Paula McCormick to work with David Cole and senior NOLS instructors on the video. One of the major challenges was condensing 75 practices and 173 book pages into a 30-minute video. In a phone conversation with McCormick, Cole suggested organizing the video around a short set of principles. The first set of six principles he proposed were:

- In popular places, concentrate use and impact.

- In pristine places, disperse use and impact.

- Stay off places that are lightly impacted or just beginning to show effects.

- Pack out everything brought into the wilderness.

- Properly dispose of anything that can’t be packed out.

- Leave things as they were or in better condition.

A seventh principle was added shortly thereafter:

- Minimize noise and intrusion.

The video was filmed in the Popo Agie Wilderness in 1990 and completed in the summer of 1991.

Compared to the disparate and often inconsistent nature of earlier educational messages, by 1991 substantial progress had been made in systematizing the Leave No Trace message. Building on the foundation provided by early proponents of low-impact education – including Wayne Anderson , Tom Alt, Jim Bradley, John Hart, and the Watermans – NOLS and the Forest Service had produced a report on practices, a booklet on general practices, regional guidelines to supplement the general practices, a full-length book, a video, and a set of LNT principles.

During this same period, steps were taken to institutionalize the dissemination of this information. Jim Currivan, wilderness program leader for the BLM’s Arizona Office, had been on the 1985 backpacking trip organized by Ratz, as well as the Third Annual NOLS Wilderness Research Colloquium, also held in the Popo Agie Wilderness. At that colloquium, Currivan and NOLS’s Drew Leemon discussed the possibility of having NOLS instructors lead a field course for BLM employees to practice arid land camping, traveling, and LNT techniques. With the support of Keith Corrigal, national director of the BLM’s wilderness program, the first course was held in the Eagletail Mountains Wilderness, Arizona, in May 1988. Five more five-day courses were conducted in BLM wilderness areas over the next three years. These courses became the prototype for the LNT Masters courses that began in 1991. The BLM also partnered with NOLS to produce a desert version of the Soft Paths video.

In 1990, the FS invited NOLS to participate and instruct in the first National Wilderness Training for Line Officers – the first time the FS devoted any significant attention to training their top level staff in wilderness management. In particular, NOLS was to take participants on a two-day camping trip, at which LNT practices could be demonstrated. NOLS instructors participated in this annual training session for many years.

The Collaborative Nature of the LNT Program Is Formalized

In 1991, efforts to bring collaboration, cooperation, and consistency to both the Leave No Trace message and how it is disseminated came together. In January, the FS decided they needed a national program to promote wilderness ethics and appointed Bill Thompson as the agency’s first national coordinator. Thompson envisioned a three-pronged approach to education – public awareness, research, and user education. In May, Thompson approached NOLS about partnering in this effort. In June, a formal Memo of Understanding (MOU) between the FS and NOLS was signed, with NOLS agreeing to pilot test one of Thompson’s proposals – a Masters of Leave No Trace course. This course would train a cadre of agency LNT Masters in skills, ethics, and training methods so they, in turn, could train more agency staff and the general public. In the fall of 1991, 10 FS and BLM managers joined with NOLS instructors to pilot test a five-day LNT Master Educators course in the Wind Rivers Mountains of Wyoming (Swain 1996).

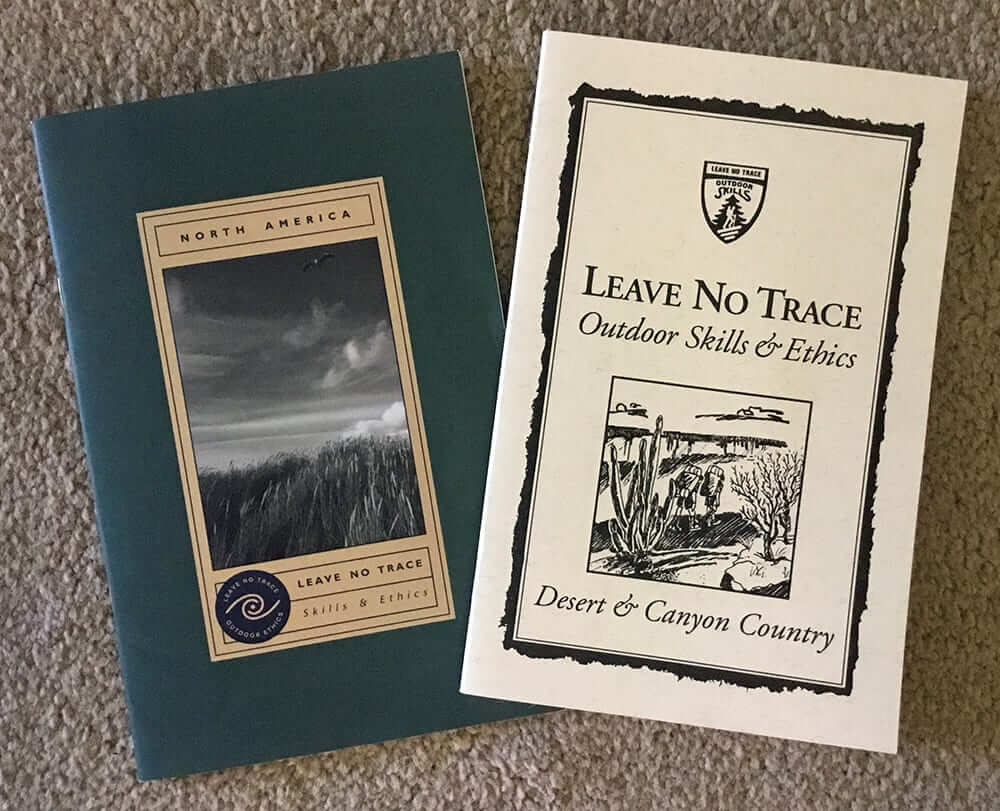

For NOLS, course logistics were simply an extension of the five-day Low Impact Arid Lands courses they had been running since 1988. They also had a wealth of material readily available for curriculum development. Their Conservation Practices booklet was the basis for a 14-page booklet on general LNT practices, published in 1991, organized according to the LNT principles first outlined in the Soft Paths video. For those interested in more detail on practices, their rationale, and their scientific basis, the Soft Paths book was available. For visual learners, there was the Soft Paths video. This general treatment was supplemented by booklets tailored to specific environments and activity types – something that was easily done given that NOLS regional guidelines had already been developed and Soft Paths had chapters specific to different environments. By 1993, five additional volumes in the LNT Skills and Ethics series were produced: Rocky Mountains, Southeastern States, Backcountry Horse Use, Western River Corridors, and Temperate Coastal Zones. Each was built around Soft Paths and the LNT principles, supplemented by research findings, local expertise, and consultation with land managers. Perhaps the greatest challenge was to develop the ethics and experiential training aspects of the LNT program, although as an outdoor leadership school, NOLS had ideas about this part of the program.

A Forest Service committee decided to name the program “Leave No Trace” – over the objections of some who felt the phrase was misleading since it is impossible to truly leave no trace. The phrase can be traced to Wayne Anderson, a resource coordinator for the Forest Service’s Pinedale Ranger District in Wyoming. Anderson was concerned about increasing impact in the Bridger Wilderness, particularly by Boy Scouts and outfitters. He developed educational materials aimed at these groups and, by 1979, had produced a slide-tape program called “Leave No Trace.” After he was transferred to the Wasatch-Cache National Forest, he made 30 copies of the slide-tape program, which he distributed to Boy Scout councils throughout the greater Salt Lake City area. By 1982, “Leave No Trace” was the phrase used to describe the wilderness skills program of the Intermountain Region of the Forest Service (Cole 1989).

Enthusiasm for national Leave No Trace programs and the train-the-trainers approach grew exponentially. Ralph Swain replaced Bill Thompson as FS national coordinator in 1991, and Stew Jacobson was appointed the first BLM national coordinator in 1992. In 1993, Roger Semler was appointed national coordinator for the National Park Service (NPS), although as was the case with Ralph Swain, this was a collateral duty. Agency coordinators met at least once annually, often at the Outdoor Recreation Retail show in Salt Lake City. They also co-instructed some Master Educators courses.

The BLM formally joined the FS-NOLS partnership in developing, promoting, and distributing LNT materials in 1993, followed by the NPS and Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) in 1994. A new Memorandum of Understanding between NOLS and the four federal agencies committed the agencies to oversight of an interagency program, with NOLS responsible for development and distribution of LNT information. For this purpose, they produced and sold booklets, videos, posters, and other materials through a website and toll-free telephone number (Marion and Reed 2001). NOLS also committed to the development and teaching of LNT Master Educators courses – many of them unique to specific environments and activity types.

Figure 6 – Two generations of region-specific Leave No Trace booklets, with the current LNT logo on the left and the earlier logo – used before Leave No Trace, Inc. was created – on the right.

The LNT principles evolved over time. Quickly added to the original six were “Plan ahead and prepare” and “Use fire responsibly.” The principle focused on impacts to other visitors suggested by Cole, “Minimize noise and visual intrusion” (McGivney 1998) was never formally adopted, presumably to limit the number of principles. By 1993, the temperate coastal zones booklet included a “Respect wildlife” principle, but this principle was not widely adopted. In 1994, the number of principles returned to six, by combining the three principles on where to travel and camp into a single principle, “Travel and camp on durable surfaces.” With the creation of Leave No Trace, Inc., that organization’s Education Review Committee assumed responsibility for making changes to the principles. Interest in principles related to wildlife and social impacts eventually led, in 1999, to the addition of the principles “Respect wildlife” and “Be considerate of other visitors” (Marion 2014). The principles related to litter and waste were collapsed into a single principle and others were rewritten slightly. Since 1999, the seven LNT principles have remained:

- Plan ahead and prepare

- Travel and camp on durable surfaces

- Dispose of waste properly

- Leave what you find

- Minimize campfire impacts

- Respect wildlife

- Be considerate to other visitors

By 1996, 300 people had graduated from LNT Masters courses (Swain 1996). By 2000, the number of trained masters was 1,122 individuals, including staff from the FS (254), BLM (121), NPS (107), FWS (4), and such organizations as the Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, Backcountry Horsemen, Outward Bound, YMCA, university educators, and people from other countries (Marion and Reed 2001). By 1996, 11 region- or activity-specific booklets and curricula had been produced, and 12 different Master Educators courses were being taught across the United States, addressing region-appropriate practices for hiking and backpacking, canoeing and rafting, sea kayaking, and backcountry horse use (Swain 1996).

Creation of the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics

One of the LNT principles, “Respect Wildlife,” can be furthered by not feeding wildlife. Photo by Jeffrey Marion.

The success and popularity of the LNT program inevitably led to tensions within and among partners. As interest in materials and courses grew, more resources had to be devoted to the program. Tensions between NOLS and the agencies surfaced, particularly as program costs rose. Other outfitting organizations – Boy Scouts, Outward Bound, and others – wanted a more active participatory role in LNT programs and trainings. As early as 1991, Jim Ratz recognized that the next step in the maturation of the LNT program would be spinning it off into its own organization. At a 1993 outdoor recreation summit, various outdoor industry and sporting trade associations, NOLS, nonprofit organizations, outdoor manufacturers, and federal land management agencies decided to create an independent nonprofit organization. This model was working successfully for motorized recreation, with the private nonprofit Tread Lightly, Inc. administering the Tread Lightly program in a manner that reduced the cost and administration of the program. Tread Lightly, Inc. had been successful in getting private motorized company partners to support the program and provide funding for materials and rehabilitation projects. It was on this premise that Stew Jacobson from BLM and Jim Miller from the FS worked with federal lawyers in Denver, Colorado, to prepare the documents for creating a 501 C3 private nonprofit, and in 1994 Leave No Trace, Inc. was born.

Headquartered in Boulder, Colorado, and now known as the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics (the Center), LNT Inc. was incorporated to develop and expand Leave No Trace training and educational resources, spread the general program components, and engage a diverse range of partners from the federal land management agencies and outdoor industry corporations to nonprofit environmental and outdoor organizations and youth-serving groups. In 1994, the Center entered into the first of a series of MOUs with the four primary federal land management agencies.

As reported by Marion and Reid (2001), the organization rapidly gained momentum with the support of 24 agency, commercial, and nonprofit partners. The organization grew from two full-time staff and a budget of $108,000 in 1996 to nine staff and $630,000 in 2000. By 2016, the Center had a budget of $1.5 million and more than 60 partners. It had 17 paid staff, a 14-member volunteer board of directors, 5 advisors from its federal land management agency partners, 48 volunteer state advocates, and more than 25,000 volunteers (Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics 2017). The Army Corps of Engineers joined the original four federal land management agencies under the MOU, and, in 2007, the National Association of State Parks Directors, the governing organization for state parks in the United States, and the Center developed a formal affiliate partnership to expand the possible use of the Leave No Trace program on state park lands.

This campsite is on the verge of becoming well-established and highly-impacted. Leave-No-Trace suggests that such sites be avoided by recreationists, who might choose either a site that is already well-impacted or a site without evidence of previous use. Missouri Lakes Basin, Holy Cross Wilderness, Colorado. Photo by USDA Forest Service.

Since 2004, the Center has developed a comprehensive, three-tiered training system, encompassing field courses such as the five-day Master Educator course and workshops that range from one hour to two days. The Center expanded Leave No Trace teaching tools adding educational activity guides, reference cards for various types of outdoor use, and expanding the number of Leave No Trace Skills & Ethics booklets for distinct activities and ecosystems to 16. A Traveling Trainer Program consisting of teams of mobile educators travels throughout the continental United States teaching Leave No Trace and providing grassroots support to build Leave No Trace education and outreach programs at the local level. Research and citizen science programs have been developed. Programs increasingly target frontcountry areas, as well as the backcountry, and an increasingly diverse array of communities and the young. By 2016, LNT programs were engaging 15 million people annually – in the United States and around the world (Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics 2017).

LNT: From Past to Future

One can think of the Leave No Trace program as having developed in three distinct stages, each with different main players. The period of initial creation lasted an indeterminate number of decades, ending about 1985. Numerous independent people, mostly field rangers, came up with the original LNT practices, largely in an independent and uncoordinated manner. Unfortunately, who these players were and what they produced will remain largely unknown, although some examples of early low-impact brochures and other printed materials remain. Nevertheless, their work provided the foundation for today’s LNT practices. The second period – one of formation, coordination, and institutionalization – lasted from 1985 through 1994. This is the period documented for the first time in this article. The main players were the land management agencies, particularly FS and BLM, FS Research, and NOLS. At the end of this period, the LNT curriculum was well established, with videos, a book, principles, and booklets for different ecosystem and activity types. Outreach and training programs were established, funded and guided by interagency LNT program managers.

The final period, one of expansion, began in 1994 with the creation of LNT, Inc. The expansion of LNT programs during this period, well-documented by Marion and Reid (2001) and at www.lnt.org, continues today. Many more players – from LNT staff to corporate sponsors, the land management agencies, academic partners, and citizens – are involved and working together in a coordinated fashion. The initial focus on backcountry and wilderness has broadened to include frontcountry areas – developed campgrounds and outdoor areas accessible by vehicle and predominately visited by day users. The Center launched two long-term initiatives in 2016: Leave No Trace in Every Park and Leave No Trace for Every Kid. Both initiatives are aimed at better reaching current and future generations with comprehensive information on enjoying the outdoors responsibly.

Some of the ecological impacts of recreation result more from inadequate management than from poor behaviors that might be changed through Leave-No-Trace education. An eroded trail in Banff National Park, Alberta. Photo by Jeffrey Marion.

As for the future, message content is likely to evolve to some degree. For some emerging issues, it will not be possible to prescribe best LNT practices until society clarifies the relative importance of different values. The burgeoning use of an ever-increasing diversity of technological devices – cell phones, GPS, and the like – is a great example (Carlson et al. 2016). How appropriate are they and how does appropriateness vary across the landscape? Smart phones with GPS capability are a great way to convey place-specific information regarding durable places to travel and camp and places to avoid, thereby reducing potential impact. They can also encourage inappropriate risk-taking and encourage more people to venture off-trail where this increased use causes unwanted trail development and impact. In Soft Paths and other early LNT materials, when there was a choice between possible behaviors – for example regarding if, where, and how to build a campfire – the alternatives were arrayed, along with their consequences, from least to most impactful, leaving people to choose how diligent to be about minimizing that particular impact. Perhaps this is how emerging issues such as technology should be dealt with.

The nature of the efforts to persuasively communicate these messages is even more likely to evolve, expand, and diversify. The Center is developing a robust human dimensions research program that will allow it to identify, explore, and implement more effective strategies for helping all who spend time outdoors reduce the adverse effects of their recreation activities. Certainly, in this era of the internet, it is much easier to get messages to potential visitors before their trips. Getting information to recreationists in the planning stages of their trip was shown early on to be one of the most effective ways to increase the efficacy of communication. It is also much easier to reinforce the same messages if people encounter them over and over in different situations. There is little reason to think that programs, outcomes, and positive results will not increase in the future. Although it is impossible to precisely quantify the positive outcome of LNT programs, in terms of less adverse impact on the environment and recreation experiences, there can be no doubt these benefits are both substantial and increasing. This is the legacy of the LNT program that slowly developed over the decades before coalescing into a prominent and successful program in the late 1980s.

Acknowledgments

The accuracy of this account was enhanced by helpful input from Rich Brame, Stew Jacobson, Ben Lawhon, Drew Leemon, Jeff Marion, Roger Semler, Skip Shoutis, and Ralph Swain. In this article, historical materials related to the origins of Leave No Trace include the 1987 revision of NOLS Conservation Practices and regional guidelines included in the 1989 report titled “Low-Impact Recreation Practices for Wilderness and Backcountry” by David Cole.

DAVID N. COLE is emeritus scientist with the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute. He retired in 2013 after a 35-year career as a wilderness scientist. Since his retirement he has been developing a History of Wilderness Science section on the Leopold Institute website, with interviews of pioneering wilderness scientists and papers documenting the history of wilderness science.

For more information on the history of wilderness science, visit the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute.

References

Berger, B. 1979. Should campfires come in a can? Sierra 65(1): 69–70.

Bradley, J. 1979. A human approach to reducing wildland impacts. In Recreational Impact on Wildlands, ed. R. Ittner et al. (pp. 222–226). Portland, OR: USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region.

Carlson, T., J. Shultis, and J. Van Horn. 2016. Technology in wilderness: Emerging issues and directions for research, policy, and management. International Journal of Wilderness 22(3): 11–17.

Cole, D. N. 1989. Low-Impact Recreational Practices for Wilderness and Backcountry. General Technical Report INT-265. Ogden, UT: USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station.

Hampton, B., and D. Cole. 1988. Soft Paths. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

Harlow, W. M. 1977. Stop walking away the wilderness. Backpacker 5(4): 33–36.

Hart, J. 1977. Walking Softly in the Wilderness: The Sierra Club Guide to Backpacking. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics. 2017. 2016 in review: Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics. Retrieved May 18, 2018 from https://issuu.com/leavenotracecenterforoutdoorethics/docs/leavenotrace_2016annualreport__1_.

Liddle, M. 1997. Recreation Ecology. London: Chapman & Hall.

Lucas, R. C. 1982. Recreation regulations – when are they needed? Journal of Forestry 80(3): 148–151.

Marion, J. 2014. Leave No Trace in the Outdoors. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

Marion, J. L., and S. Reid. 2001. Development of the United States ‘Leave No Trace’ programme: A historical perspective. In Enjoyment and Understanding of the Natural Heritage, ed. M. B. Usher. Scottish National Heritage, Edinburgh. The Stationery Office Ltd., Scotland.

McGivney, A. 1998. Leave No Trace: A Guide to the New Wilderness Etiquette. Seattle: The Mountaineers.

Petzoldt, P. 1974. The Wilderness Handbook. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

Snyder, A. P. 1966. Wilderness management – A growing challenge. Journal of Forestry 64: 441–446.

Swain, R. 1996. Leave No Trace (LNT) – Outdoor skills and ethics program. International Journal of Wilderness 2(3): 24–26.

Waterman, L., and Guy Waterman. 1979. Backwood Ethics: Environmental Concerns for Hikers and Campers. Boston: Stone Wall Press.

Read Next

Apologizing for Science-Based Decision Making in Protected Area Management

Apologizing for science promotes autocratic management that can easily be commandeered by sociopolitical agendas and bureaucratic systems.

Wilderness Giant: Stewart “Brandy” Brandborg Moves on at 93

Steward Brandborg was a phenomenal wilderness champion, the last wilderness advocate with ties to most of the founders of the modern wilderness movement.

Cultural Meanings and Management Challenges: High Use in Urban-Proximate Wildernesses

As outdoor recreation increases in popularity and metropolises grow larger, the issues facing urban-proximate wilderness and protected lands will continue to come to the forefront.