International Perspectives

June 2017 | Volume 23, Number 1

By PETER ASHLEY

Wilderness can be a place for human transformation, with the wilderness experience increasingly recognized as being restorative and a positive contributor to psychological well-being (Talbot and Kaplan 1986; Kaplan and Kaplan 1989; Scherl 1989; Harper 1995; Mace et al. 2004; Garg et al. 2010; Hinds 2011; Ewert et al. 2011; DPIPWE 2014; European Wilderness Society 2014).

Restorative benefits from the wilderness experience include tranquility and inner peace (Kaplan and Kaplan 1989; Cumes 1998); calmness, relaxation, refreshment, revitalization (White et al. 2013), and mental and physical renewal (Talbot and Kaplan 1986); changes in perception, enjoyment, fascination, and sensory awareness (Kaplan and Talbot 1983); a sense of wholeness (Kaplan and Kaplan 1989); self-discovery, confidence, and well-being (Hinds 2011); self-insight and expansion of the “self ” (Kaplan and Talbot 1983; Greenway 1995); and personal and interpersonal (social) development (Hine et al. 2011).

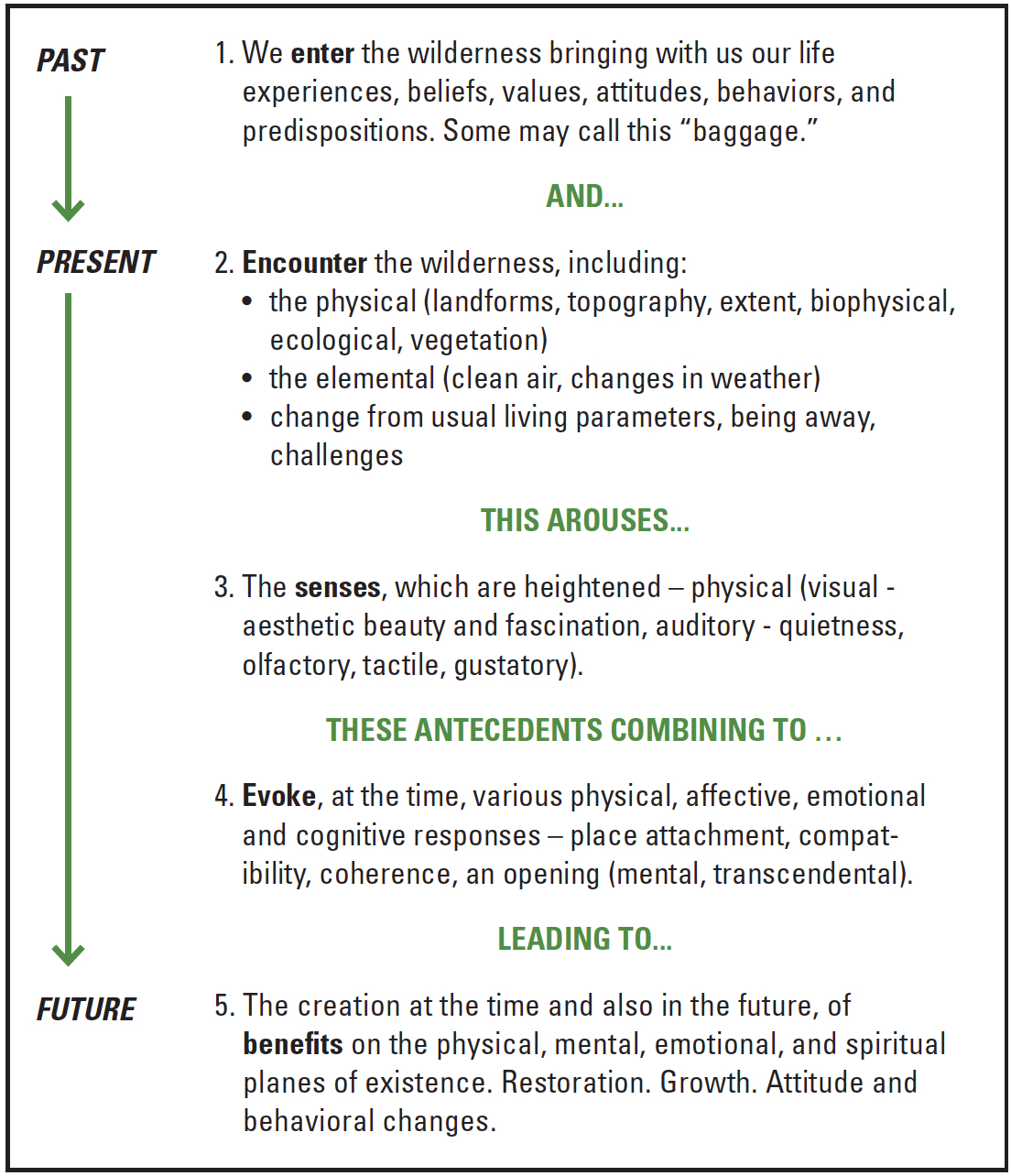

While past research confirming the restorative and psychological benefits attributable to wilderness experiences is persuasive, little work has been done on plotting the mechanisms responsible. A coherent and integrated approach is needed to advance the field. Identification of possible factors would increase our knowledge of the restorative value of wilderness and contributes to what Watson (2004) described as a new era of public land stewardship – stewarding the relationship between people and wilderness. Understanding those relationships and their influences allows managers to manage for their protection. In this article, a multidimen- sional conceptual framework is proposed – the wilderness experience pathway schema (WEPS) (Figure 1) – potentially causal to explaining the “psychological wilderness response.”

The Wilderness Experience Pathway Schema (WEPS)

While models have been developed to explain the relationship between natural areas such as wilderness and health, restorative, transformational, and spiritual benefits (see for example, Ulrich 1983; Fox 1999; Heintzman 2009a, 2011; Fredrickson and Anderson 1999; Ewert et al. 2011; Scannell and Gifford 2010), no one model fully encapsulates the complex nature of the human-environment relationship nor fully illustrates the linkages between the parts and the whole within a wilderness context. A more inclusive and integrated model is called for, such as that offered by the WEPS.

The multidimensional framework proposed here structures possible causal mechanisms for the wilderness psychological response and consequent restorative and associated benefits via a five-phase sequence of events (Figure 1). However, some qualifying comments may be useful here before proceeding. Spiritual values and benefits, sometimes considered analogous to psychological values and benefits (e.g., Kaplan and Talbot 1983; Bennett 1994; Johnson 2002; Ewert et al. 2011; European Wilderness Society 2014), are not dismissed, but the focus of the WEPS is on psychologically restorative outcomes in the wilderness setting. Likewise, conceptual aspects of other fields of research such as leisure studies and outdoor and recreation experience may be present, but they are beyond the scope of this article. Consequently, there may be some cross-pollination between fields in the schema. This is almost impossible to avoid (as is the case in most models) when overlapping concepts and potential variables are squeezed into a diagrammatic representation of the human: environment relationship with all its complexities.

Returning to the five phases (Figure 1), the first phase involves people’s entry into wilderness: What cognitions, expectations, and predispositions do we bring with us when we arrive? The second phase covers the encounter with the wilderness setting: How are the wilderness characteristics perceived? These two phases, collectively, give rise to the third phase, arousal of the senses: What is stimulated and what are the triggers? Acting in concert, the preceding three phases produce the fourth phase: What is evoked? The fifth and final phase represents the products of the wilderness experience: What outcomes and benefits may be expected and when?

Entry Phase

In the beginning, we come to wilderness. While we may leave behind our routines and the stresses associated with contemporary living (Brady 2006) and cultural overstimu- lation (Greenway 1996), we are far from inert. What we bring – our states and traits, fears and phobias, predispositions, values, value orientations, attitudes, and motivations for being there – may well influence how we perceive wilderness and what we expect or want from the trip.

Thus the characteristics of our persona upon arrival “set the scene” emotionally and cognitively, even behaviorally, and may determine the form, strength, and duration of any subsequent restorative outcomes by either encouraging or inhibiting them. What we bring to the wilderness (above) as psychometric variables can be overlooked in wilderness studies tending toward recreation and experiential preferences related to setting characteristics, but need to be taken into account in order to provide a more grounded explanatory framework for the psychological response. This is an important foundational differentiation of the WEPS approach.

Encounter Phase

We now transition into, or encounter, wilderness, this second phase covering the biophysical environment – the natural setting characteristics including the weather. General wilderness conditions thought likely to foster the psycho-spiritual response include conditions of sound and quiet deemed essential to maintain the solitude and primitive character of wilderness (Briggs et al. 2011) and naturalness (Dawson and Hendee 2009; Ryan et al. 2010). Specific natural setting characteristics or interactions with them believed to trigger psycho- spiritual experiences in wilderness include physical challenge, wildlife, water bodies, geology, vegetation, high places, open and expansive or closed-in and protected natural areas, and environmental quality and integrity or naturalness (Fredrickson and Anderson 1999; McDonald et al. 1989).

A fundamental issue is the uncertainties and even fears relative to the weather (Kaplan and Talbot 1983) potentially playing a significant role in wilderness areas by being an ally or antagonist mediating one’s experience depending on circumstances (Ashley 2009). Although wilderness weather has been recognized as a contributing factor to a spiritual experience, for example (Stringer and McAvoy 1992), this contribution is more likely to apply if the weather is kind, I think. But wild country does have an “aura of danger,” enough to approach it with “humble caution” Graber (1976, p. 12). Wilderness may not always be a carpet of flowers, it confronts us with “gray rainy days, animal-fouled water, perilous forests, and deathly dangers” requiring attention to all that surrounds us (Harper 1995, p. 187) – such confrontations and challenges being offered up spontaneously and sometimes in great number (Cumes 1998). Thus traveling in wilderness areas, particularly if backpacking on foot, carries a risk that one may be presented with significant mental and physical challenges (McDonald et al. 2009; Kaplan and Kaplan 1989), including “moments of serious emotional stress” (Harper 1995, p. 193). It is not to be forgotten that well-known Tasmanian wilderness photographer Peter Dombrovskis (see front cover photograph IJW, April 2006; Mittermeier 2005) died in the rugged Tasmanian southwest wilderness alone, as did his mentor Olegas Truchanas, in separate incidents.

Senses Phase

This third WEPS phase involves the role of the five senses in the wilderness experience. Kaplan and Talbot (1983, p. 177) for example, reported that participants in the Outdoor Challenge program became more aware of their surroundings after a few days, noticing clouds, birds, and animals and the “smells, sights and sounds” of the landscape. Greenway (1996, p. 26) has also confirmed that in wilderness, “ears, eyes, nose, and skin open in wonder, wider and wider, colors, smells, and shapes becoming more vivid”. Experienced through sensation, the effect of the wilderness landscape is aptly described by Johnson (2002, p. 30):

We enter wilderness with all our senses and all our being: feeling the rain or breeze; smelling its pine and sage; hearing the water, the crack of lightning; seeing the world anew with each shift of light or perspective; not least, we know in our elemental core how our journey has entwined us – our comfort and our fate – with this landscape.

To experience the full restorative potential of wilderness, Cumes (1998, p. 93) has suggested that we need to become one with the wilderness encounter, to “feel, touch, smell, and taste as well as see and hear it,” this letting the wilderness in via enlivening the senses being a subtly powerful and underrated perceptual experience (Harper 1995).

The multifaceted beauty of wilderness areas (Cumes 1998) offers opportunities for aesthetic pleasure (Fox 1999). Aesthetic natural settings are not only pleasing to the eye but also foster mental-fatigue recovery and effective human functioning (Kaplan and Kaplan 1989). The aesthetic response is triggered by landscapes with moderate to high complexity, structural properties displaying patterns and a focal point, moderate to high level of visual depth or openness, homogenous and mobility-attracting surfaces, water features, and those that appear to be unthreatening (Ulrich 1983). More specifically, the study of McDonald et al. (2009) found that the aesthetic quality of the wilderness landscape was the most important of seven themes in triggering peak experiences for participants, notably sunlight, late afternoon sunsets, forests, mountains, wildlife, and valleys. These visual cues, along with watching clouds and the movement of leaves in the wind and other sensory stimuli such as sounds and smells (Cumes 1998), may account for restorative and transcendent experiences in natural settings (Williams and Harvey 2001).

Evocation Phase

This fourth phase accounts for the physical, affective, and cognitive reactions to the previous two trigger phases.

After spending some time in wilderness, a feeling may arise, a sense that we are not strangers or outsiders but instead belong there, a feeling that we are “at home” (Harper 1995, p. 187), Greenway (1996, p. 27) confirming that such an articulation by his study participants was an indication they were transitioning or “crossing into wilderness psychologically as well as physically.” Our perception of time and space may also radically shift, people reporting a sense of timelessness as they become more attuned to natural rhythms, creating an opening for new experiences through “the natural dynamics of wilderness” (Greenway 1995, p. 130). In their study, Williams and Harvey (2001) found that a sense of timelessness was one of the characteristics of a transcendent experience in forests, for example. Dreams may also change. A Greenway (1995) finding was that after three or four days in wilderness, 82% of respondents reported that the content of their dreams changed from urban or busy scenarios at the beginning of the trip to those about wilderness or their group.

With feelings of connection and oneness being recognized as part of a wilderness spiritual experience (Fox 1999; Stringer and McAvoy 1992), McDonald et al. (2009) also found that feelings of connection or belonging to wilderness, of being at one with wilderness, helped trigger peak experiences. But it can be about connection with other people too, through the sharing of leisure pursuits (Heintzman 2009b). Where there is a good fit between an individual and whatever (recreational) pursuits are being undertaken in wilderness – whether high-risk adventure such as climbing (Figure 2) or more sedate pursuits such as photography – and if one feels at ease doing them, this “state of mind” becomes an important aspect of reflection (Kaplan and Kaplan 1989, p. 200).

Figure 2 – A happy soul – compatibility exemplified. The author’s son climbing in the Andes. Photo by James Ashley.

Benefits Phase

The simple act of going into wilderness “can have profound healing consequences” (Cumes 1998, p. 34), wilderness being a physically and mentally different place away from the usual pressures and concerns of everyday existence (Schmidt and Little 2007; McDonald et al. 2009). This awayness can contribute to spiritual experiences in wilderness (Heintzman 2009b), and along with aesthetics (senses phase), was found by McDonald et al. (2009) to be the most influential of seven themes in triggering peak or transcendent experiences in wilderness. The Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service (1999, p. 25) confirms that the (Tasmanian) wilderness experience can be “therapeutic and character–building,” with the results of a Canadian wilderness river rafting study supporting the psychologically restorative potential of wilderness (Garg et al. 2010).

Following analysis of the trip journals of participants in the Outdoor Challenge program, Kaplan and Talbot (1983, p. 192) found a progression of responses to wilderness or “temporal landmarks,” indicating that beneficial effects tend to accumulate over the duration of a wilderness trip of around seven days. Based on fascination, coherence, and compatibility as primary factors, participants felt invigorated and refreshed, more self-confident and tranquil, better able to contemplate their future goals and priorities, had experiences of awe and wonder leading to “thoughts about spiritual meanings and eternal processes” (Kaplan and Talbot 1983, p.178), and took “a more proactive stance toward the environment at least personally” (p. 195). Similarly, where events in wilderness may be adjudged as spiritually inspirational and thus temporally immediate, subsequent benefits off-site could lead to “a more psychologically-balanced state of being and environmentally-sound way of being in the world” (Fredrickson and Anderson 1999, p. 23).

Significantly, the testing nature of the wilderness landscape (encounter phase) can offer infinite rewards, as facing and overcoming the physical and mental challenges it often presents can stimulate or trigger positive and profound feelings contributing to spiritual experiences (Stringer and McAvoy1992) and otherwise improving one’s psychological well-being (Kaplan 1995; Fredrickson and Anderson 1999; Williams and Harvey 2001; Ulrich et al. 1991; Schmidt and Little 2007; Kirchhoff and Vicenzotti 2014; Cumes 1998; Hine et al. 2011; McDonald et al. 2009).

Framework Testing

The WEPS assumes that there may be some overlap in the five phases, but they may also be separate. Furthermore, progress “through” the phases may not necessarily be unidirectional, although the first phase (wilderness entry states and traits) is expected to have universal applicability and be the first order phase regardless. It is also possible that some people may not necessarily experience each of the four remaining phases, while others may experience them all and simultaneously (Ashley 2009), or in a different order, with pathways being less a reductionist linear progression and more cyclic in practice due to the complexity (Fredrickson and Anderson 1999; Heintzman 2009a) and multidimensionality of the wilderness experience. It is also acknowledged that different types of wildernesses, setting characteristics, activities, and such like may also influence experiences. Consequently, the WEPS as proposed will need to be validated.

Implications for Wilderness Management

The WEPS has the potential to inform wilderness management processes. However, we cannot foster people’s immanent experiences of wilderness directly – that is in their hands – but we can foster the conditions conducive to those experiences, or at least thought likely to do so, by creating opportunities for experiences such as for solitude (Cole 2011). It might also be more about the choices that visitors make when in wilderness than management actions together with the knowledge and understanding managers have of the possibility of or potential for psycho- spiritual outcomes (Heintzman 2011). The WEPS may help increase such knowledge and understanding.

Practically, managers need to know “what they are managing for” (Cole 2011, p. 69). By focusing on the encounter, sensory awareness, and evocations phases in this section, the WEPS could provide this direction, although it really gets down to what managers can control or not (Cole 2004).

In the encounter phase, then, wilderness conditions thought likely to foster psycho-spiritual experiences include the relative absence of development (Heintzman 2011) and naturalness (Dawson and Hendee 2009; Ryan et al. 2010). This is achievable by reducing management infrastructure such as roads (Ashley 2009) and maintaining and restoring ecosystems, for example. Tracks could be routed to take advantage of particular landscape features such as wildlife, water bodies, geology, vegetation, and high places (Fredrickson and Anderson 1999; McDonald et al. 1989). And with Cole (2004) counting the social setting as a setting attribute, managers can control the extent, amount, and type of use – although visitor behavior less so, this social aspect having the potential to influence the restorative potential of wilderness in one way or another.

As to sensory aspects, conditions subject to management actions include sound and quiet deemed essential to maintain the solitude and primitive character of wilderness (Briggs et al. 2011). Contraindicators include human-sourced noise and ambient stressors such as air pollution causing haze and visibility problems. Scenic vistas obscured by air pollution may have consequences that are “heavily psychological,” indicating annoyance, stress, and depression (Mace et al. 2004, p. 7). Experiences can also be compromised by noise from overflying aircraft, motorized snow vehicles and watercraft, and off-road vehicles in wilderness areas (Mace et al. 2004). Managers can protect viewsheds by controlling fire (as much as possible), and therefore smoke, and in terms of sound, by limiting the noise signatures of motorized conveyances, including overflying aircraft. Development of a soundscape management plan for some areas based on acoustical data would improve the visitor experience and general ecosystem health (Briggs et al. 2011).

Finally, the evoke phase is less subject to direct management control. The creation of place attachment meanings (e.g., love of place, feeling at home, being in place), respect for nature and wilderness, and development of an environmental/wilderness ethic expected in the evoke phase, are largely in the hands of visitors. However, it is not beyond the realm of possibility that managers might influence these sorts of expressions, which, by the way, may well accord with their own values anyway. A helpful and caring attitude toward place, people, and wildlife by managers; the manner in which their duties are undertaken; teamwork; and their passion, for example, may help shape visitors’ evocations should they be noticed by visitors at the time or subsequently.

Conclusion

When we are in wilderness we embark on two journeys – the outer and the inner. While both are entwined, this article is essentially about the latter. The context is the demystification and clarification of the human response considered causal to restorative and other beneficial well-being outcomes. This article identifies the underlying precepts of the human psychological response to wilderness and organizes them into a multidimensional framework and schema. As such, it takes steps toward filling a gap in the environmental psychology and wilderness literature. Further research and framework testing in practical domains would be expected to provide additional support (or not) for the WEPS structure and nuance the elements within each phase and their role. As the pace of the world becomes progressively speedier and as rates of mental distress and dis-ease increase, wilderness offers a place of refuge from the vicissitudes of modern life. A powerful “catalyst for change” (Ashley 2012, p. 8), if you wanted to stop the world and get off, you would probably want to alight into wilderness.

PETER ASHLEY is a university associate, Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Tasmania; email: plashley@ utas.edu.au.

VIEW MORE CONTENT FROM THIS ISSUE

References

Ashley, P. 2009. The spiritual values of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area and implications for wilderness management. Unpublished PhD thesis, School of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart. 2012. Confirming the spiritual value of wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 18(1): 4–8.

Bennett, D. 1994. The unique contribution of wilderness to values of nature. Natural Areas Journal 14(3): 203–208.

Brady, E. 2006. Aesthetics in practice: Valuing the natural world. Environmental Values 15(3): 277–291.

Briggs, J., J. Rinella, and L. Marin. 2011. Using acoustical data to manage for solitude in wilderness areas. Park Science 28(3): 81–83.

Cole, D. N. 2004. Wilderness experiences: What should we be managing for? International Journal of Wilderness 10(3): 25-27. 2011. Wilderness visitor experiences: A selective review of 50 years of research. Park Science 28(3): 66–70.

Cumes, D. 1998. Inner Passages, Outer Journeys: Wilderness, Healing, and the Discovery of Self. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications.

Dawson, C. P., and J. C. Hendee. 2009. Wilderness Management: Stewardship and Protection of Resources and Values, 4th ed. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

DPIPWE (Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment). 2014. Draft Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Management Plan. Hobart, Tasmania: DPIPWE.

European Wilderness Society. 2014. European Wilderness Quality Standard and Audit System: Working Draft, Version 1.4. Retrieved September 22, 2016, from http://wilderness-society.org/wp-content/ uploads/2014/02/EWQA_working- definition-Final.pdf.

Ewert, A., J. Overholt, A. Voight, and C. C. Wang. 2011. Understanding the transformative aspects of the wilderness and protected lands experience upon human health. In Science and Stewardship to Protect and Sustain Wilderness Values: Ninth World Wilderness Congress Symposium, 2009, 6–13 November, Meridá, Yucatán, Mexico, comp. A. Watson, J. Murrieta-Saldivar, and B. McBride (pp. 140–146). Proceedings RMRS-P-64. Fort Collins, CO: USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Fox, R. 1999. Enhancing spiritual experience in adventure programs. In Adventure Programming, ed. J. C. Miles and S. Priest (pp. 455–461). State College, PA: Venture Publishing.

Fredrickson, L. M., and D. H. Anderson. 1999. A qualitative exploration of the wilderness experience as a source of spiritual inspiration. Journal of Environmental Psychology 19(1): 21–39.

Garg, R., R. T. Couture, T. Ogryzlo, and R. Schinke. 2010. Perceived psychosocial benefits associated with perceived restorative potential of wilderness river-rafting trips. Psychological Reports, 107(1): 213–226.

Graber, L. H. 1976. Wilderness as Sacred Space. Washington, DC: The Association of American Geographers.

Greenway, R. 1995. The wilderness effect and ecopsychology. In Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind, ed. Roszak, M. E. Gomes, and A. D. Kanner (pp. 122–135). San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.1996. Wilderness experience and ecopsychology. International Journal of Wilderness 2(1): 26–30.

Harper, S. 1995. The way of wilderness. In Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind, ed. T. Roszak, M. E. Gomes, and A. D. Kanner (pp. 183–200). San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

Heintzman, P. 2009a. Nature-based recreation and spirituality: A complex relationship. Leisure Sciences 32(1): 72–89. 2009b. The spiritual benefits of leisure. Leisure/Loisir 33(1): 419–445. 2011. Spiritual outcomes of wilderness experience: A synthesis of recent social science research. Park Science 28(3): 89–92, 102.

Hinds, J. 2011. Exploring the psychological rewards of a wilderness experience: An interpretive phenomenological analysis. The Humanistic Psychologist 39(3): 189–205.

Hine, R., C. Wood, J. Barton, and J. Pretty. 2011. The Mental Health and Wellbeing Effects of a Walking and Outdoor Activity Based Therapy Project. Essex, UK: University of Essex Department of Biological Sciences and Interdisciplinary Centre for Environment and Society.

Johnson, B. 2002. On the spiritual benefits of wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 8(3): 28–32.

Kaplan, R., and S. Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kaplan, S. 1995. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 15(3): 169–182.

Kaplan, S., and J. F. Talbot. 1983. Psychological benefits of a wilderness experience. In Behavior and the Natural Environment, ed.I. Altman and J. F. Wohlwill (pp. 163–203). New York: Plenum.

Kirchhoff, T., and V. Vicenzotti. 2014. A historical and systematic survey of European perceptions of wilderness. Environmental Values 23: 443–464.

Mace, B. L., P. A. Bell, and R. J. Loomis. 2004. Visibility and natural quiet in national parks and wilderness areas: Psychological considerations. Environment and Behavior 36(1 ): 5–31.

McDonald, B., R. Guldin, and G. R. Wetherhill. 1989. The spirit in the wilderness: The use and opportunity of wilderness experience for spiritual growth. In Wilderness Benchmark 1988: Proceedings of the National Wilderness Colloquium: January 13–14, 1988, Tampa, FL, comp. H. R. Freilich (pp. 193–207). Gen. Tech. Rep. SE-51. Asheville, NC: USDA Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station.

McDonald, M. G., S. Wearing, and J. Ponting. 2009. The nature of peak experience in wilderness. The Humanistic Psychologist 37(4): 370–385.

Mittermeier, C. 2005. Conservation photography: Art, ethics, and action. International Journal of Wilderness 11(1): 8–13.

Ryan, R. M., N. Weinstein, J. Bernstein, K. W. Brown, L. Mistretta, and M. Gagné. 2010. Vitalizing effects of being outdoors and in nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology 30: 159–168.

Scannell, L., and R. Gifford. 2010. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 30: 1–10.

Scherl, L. M. 1989. Self in wilderness: Understanding the psychological benefits of individual-wilderness interaction through self-control. Leisure Sciences 11(2): 123–135.

Schmidt, C., and D. E. Little. 2007. Qualitative insights into leisure as a spiritual experience. Journal of Leisure Research 39(2): 222–247.

Stringer, L. A., and L. H. McAvoy. 1992. The need for something different: Spirituality and the wilderness adventure. The Journal of Experiential Education 15(1): 13–21.

Talbot, J. F., and S. Kaplan. 1986. Perspectives on wilderness: Re-examining the value of extended wilderness experiences. Journal of Environmental Psychology 6(3): 177–188.

Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service. 1999. Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Management Plan. Hobart: Parks and Wildlife Service.

Ulrich, R. S. 1983. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment, ed. I. Altman and J. Wohlwill (pp. 85–125). New York: Plenum.

Ulrich, R. S., U. Dimberg, and B. L. Driver. 1991. Psychophysiological indicators of leisure benefits. In Benefits of Leisure, ed. B. L. Driver, P. J. Brown, and G. L. Peterson (pp. 73–89). State College, PA: Venture Publishing.

Watson, A. E. 2004. Human relationships with wilderness: The fundamental definition of wilderness character. International Journal of Wilderness 10(3): 4–7.

White, M. P., S. Pahl, K. Ashbullby, S. Herbert, and M. H. Depledge. 2013. Feelings of restoration from recent nature visits. Journal of Environmental Psychology 35: 40–51.

Williams, K., and D. Harvey. 2001. Transcendent experience in forest environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology 21(3): 249–260.