Science & Stewardship

June 2017 | Volume 23, Number 1

by C. B. GRIFFIN

Once a US wilderness is congressionally designated, land management agencies must manage it to preserve its wilderness character. Wilderness character is defined by five qualities: untrammeled, natural, undeveloped, solitude or primitive and unconfined recreation, and other features of value (Landres et al. 2015). The first priority in the 2020 Vision: Interagency Stewardship Priorities for America’s National Wilderness Preservation System (BLM et al. 2014), is that by 2020 all four land management agencies will have completed their wilderness character inventories to document the wilderness character in each wilderness.

Even though solitude or primitive and unconfined recreation is one quality of wilderness character, the latest interagency guidance on how to measure it uses two indicators to measure solitude, one indicator to measure primitive recreation, and one indicator to measure unconfined recreation (Landres et al. 2015). This research project focuses on unconfined recreation. Unconfined recreation was selected because management restrictions or rules on recreational activities are very visible to users; they are commonly posted on signs and kiosks at trailheads and they are listed in various locations on agency websites.

Unconfined recreation occurs when there are minimal or no restrictions on visitor behavior. Federal agencies manage for unconfined recreation by attempting to have a rule-free recreation experience for visitors. However, agencies are allowed to make rules that restrict visitor freedom – either to protect the wilderness itself or to protect visitor experience (for example, visitors should experience solitude in wilderness, which an agency may try to protect by limiting group size). Managers must balance providing unconfined recreation with preserving the other qualities that define wilderness character.

The goal of the project is to describe the state of unconfined recreation in the wildernesses that make up the US National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Specifically, it will describe the state of unconfined recreation managed by two of the four agencies – the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Forest Service (FS). These two agencies manage most of the wilderness units in the United States (669 of the 801 wildernesses). While this research does not reflect all of the wildernesses in the NWPS or all of the qualities of wilderness character, it serves as an important first step in quantifying one of the qualities of wilderness character.

Unconfined Recreation in Wilderness

Managers try to use indirect techniques such as education (e.g., Leave No Trace principles) before resorting to direct techniques such as rules to influence user behavior (Dawson and Hendee 2009) in part because it allows users to make choices. Both indirect and direct techniques are designed to protect nature and the user experience. Although increasing rules can help preserve ecological health and user experiences, it is the antithesis of unconfined recreation (Manning 2011). In a comprehensive review of the literature, Manning found that users support some rules (e.g., group size limits) but oppose others such as prohibiting campfires.

An interagency group met to develop a document to help agencies develop ways to measure and monitor wilderness character. The document, Technical Guide for Monitoring Selected Conditions Related to Wilderness Character (Landres et al. 2009), has been widely used by agencies as they develop their wilderness character studies. The Technical Guide provides a list of the main types of potential rules that a manager can use to regulate recreation in wilderness. The 11 broad categories of rules are:

- campfire restriction

- camping restrictions

- fees

- permits

- human waste

- length of stay

- stock use

- swimming/bathing

- area closure

- group size limits

- dogs/domesticated animals

Virtually every wilderness character report written for the BLM, FS, FWS (Fish and Wildlife Service), and NPS (National Park Service) contains the listing of recreation-related rules that are described in the Technical Guide. These rules exist on a continuum from no restrictions (weighting=0) to intensive restrictions (weighting=3). The weighting of each rule can be modified by the geographic extent of the rules: less if it only affects a portion of the wilderness or more if it affects the entire wilderness. All of the rules applicable to a wilderness are added together to form a composite score known as the index of management (or visitor) restrictions.

Methods

There are various sources of data that could be used to describe the level of unconfined recreation that exists in wilderness areas: information posted at the trailhead for each wilderness, agency websites, wilderness character reports, and the database of all agency rules affecting recreation housed at www.wilderness.net. Trailheads are an impractical method for collecting information on the scale of the entire country. Agency websites, while potentially the most current of the sources, lack consistency in terms of where the rules are located for each wilderness. Because fewer than half of the wilderness character reports are completed, it isn’t a complete dataset. Thus, the interagency, publicly accessible, centralized database from www.wilderness.net was used to obtain recreation-related rules in wilderness (hereafter referred to as “the database”). The database is housed by the interagency Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center and the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute in collaboration with the University of Montana.

All four agencies are asked annually to update the rules for each of the wildernesses they manage using a standard template, thus ensuring a measure of uniformity in the database. The database for the wildernesses managed by the BLM and FS is comprehensive, whereas the database for the FWS and NPS wildernesses is incomplete based on comparing agency websites with the information at www.wilderness.net. For example, there are no rules listed for Rocky Mountain National Park’s wilderness on the site, yet the agency website has many rules associated with it. On the www.wilderness.net site, Big Lake Wilderness, managed by the FWS, states that there are many rules that must be followed, but no rules are explicitly stated on the www.wilderness.net database. As such, the FWS and NPS wildernesses were excluded from this research.

Every wilderness has its own home page on www.wilderness.net. The tabs common to each page include a general overview, maps, contacts, area management, and wilderness laws. Only the area management page was evaluated (wilderness laws contains a listing of the congressional laws that affect the wilderness). The only rules that were excluded from this analysis were general prohibitions found in the Wilderness Act itself (e.g., banning mechanized or motorized travel unless the enabling legislation for a wilderness allows an exception).

An initial spreadsheet was created using the broad categories of rules described in the Technical Guide (Landres et al. 2009). While the Technical Guide has 11 categories of rules, during this research project the categories were expanded to 19 to more fully account for all of the types of rules that were present (see Figure 3 for the 19 categories). Each of the general categories of rules was subdivided into unique rules (e.g., no fires within X distance of a lake, no fires within Y distance of a trail). Some categories of rules have more types of possible rules than other categories (e.g., stock has 49 individual rules whereas hunting has only 3). There were more than 350 unique rules in the dataset.

One of the methodological challenges of using the database was determining if the rule really has the force of law or whether it was a suggestion. Unless the information for a wilderness was very clearly a suggestion it was recorded as a rule, as the www.wilderness.net site’s header is “wilderness-specific regulations.” One rare case where the language in the database was not treated as a rule was the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness in Idaho. The verbiage on www.wilderness.net – before the listing of the “rules” – said “Suggested activities for visitors”; thus, it was treated as a suggestion, much like the Leave No Trace (LNT) principles.

Another challenge was determining whether a rule was confining recreational activities. The Technical Guide expressly acknowledged that it didn’t list all rules, especially rules that “do not present significant confinement of the visitor (such as anti-littering regulations).” For this project, there was no attempt made to determine if the rule represented a significant confinement of the visitor, thus, anti-littering regulations appear in this dataset. Coding rules could be developed – and consistently applied – for what constitutes a rule that confines recreational activities, but that should be done with extensive consultation with agency personnel and other wilderness researchers.

Results

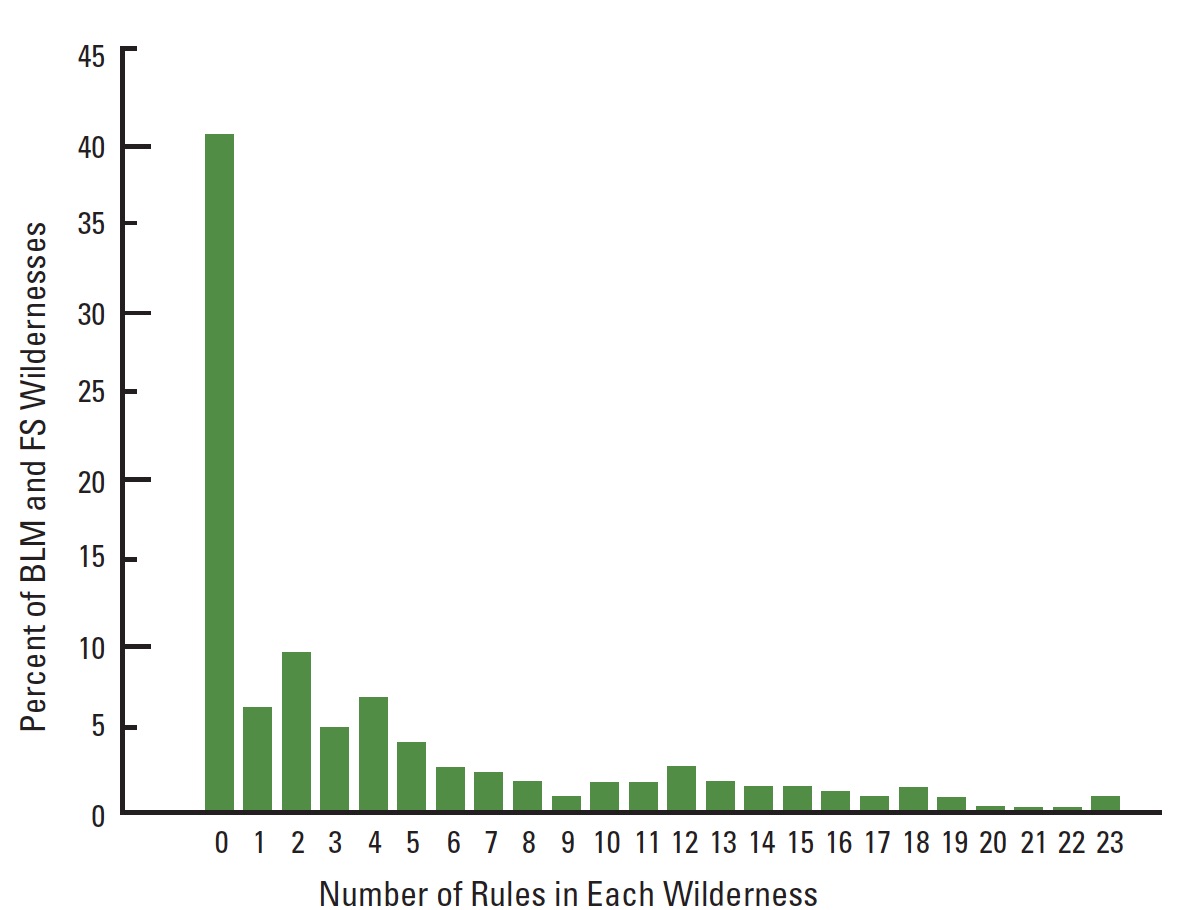

Every BLM (n=224) and FS (n=445) wilderness in the database was examined for this research. Forty-one percent of BLM and FS wildernesses had no recreation-related rules. Thirty-two percent of the wildernesses had one to five rules (Figure 1). The Sawtooth Wilderness in Idaho had the most rules (29) followed by the John Muir Wilderness in California (28) and Maroon Bells Wilderness in Colorado (26). All three wildernesses are managed by the FS.

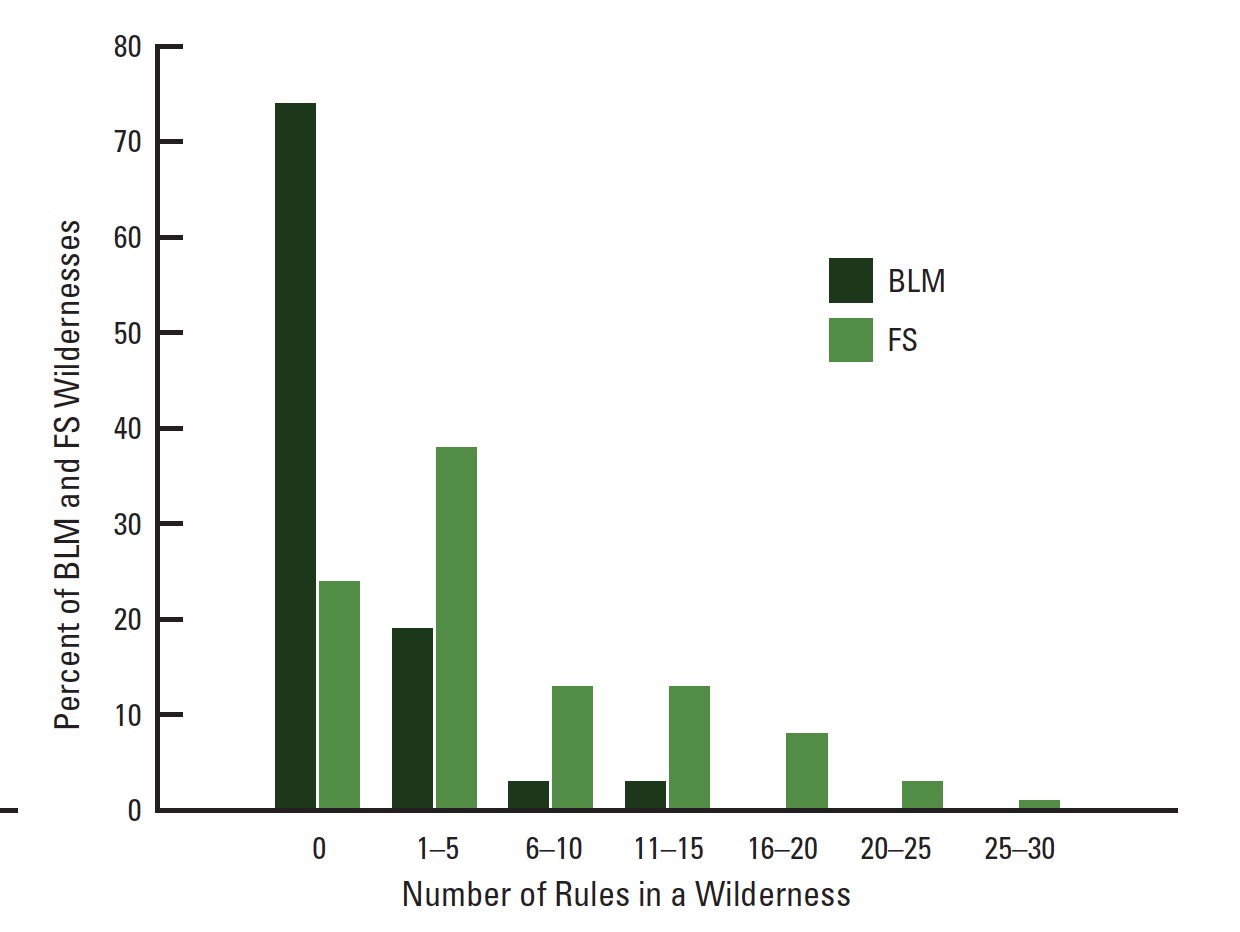

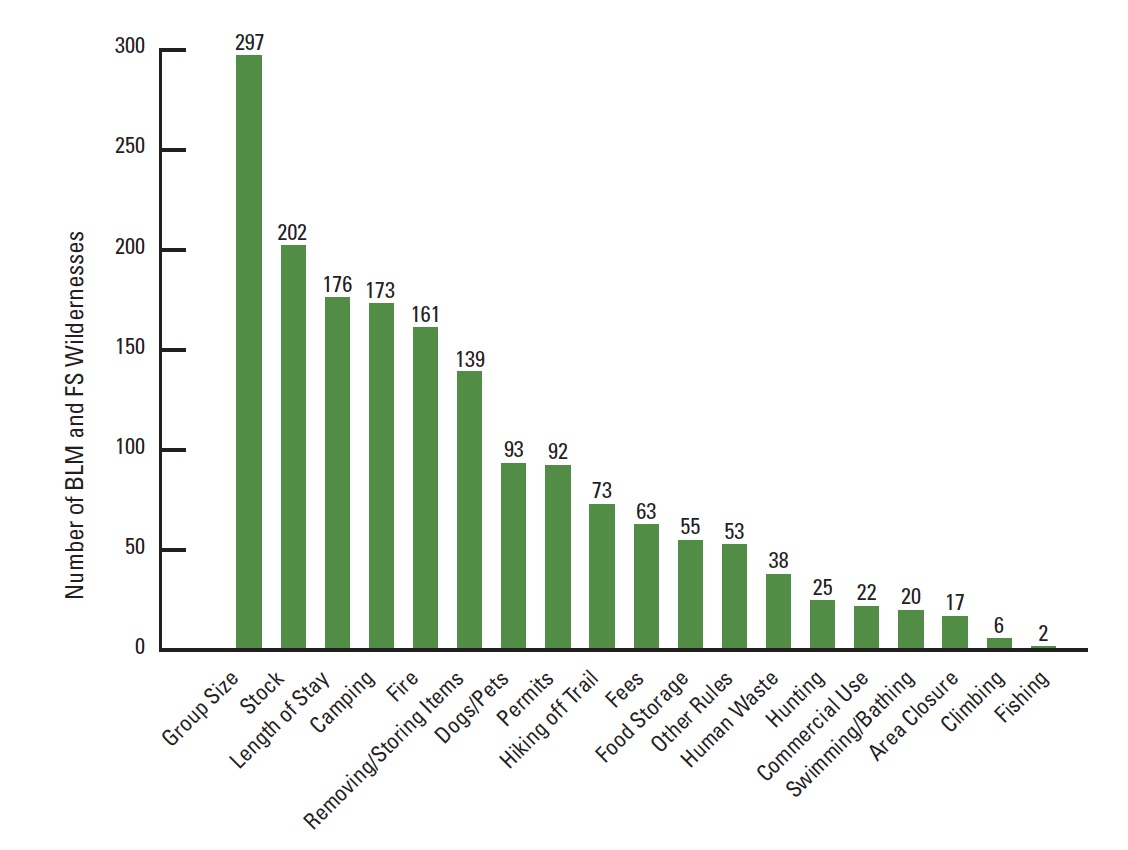

Most (74%) of the BLM wildernesses had no recreation-related rules (166 of the 224 wildernesses) (Figure 2). In contrast, 76% of the FS wildernesses did have rules (334 of the 445 wildernesses). The FS also had twice as many wildernesses with one to five rules as the BLM. The most frequent category of rule was group size limits (44% of wilder- nesses) and stock rules (30%) (Figure 3). Few wildernesses have rules about fishing (n=2) or climbing (n=6).

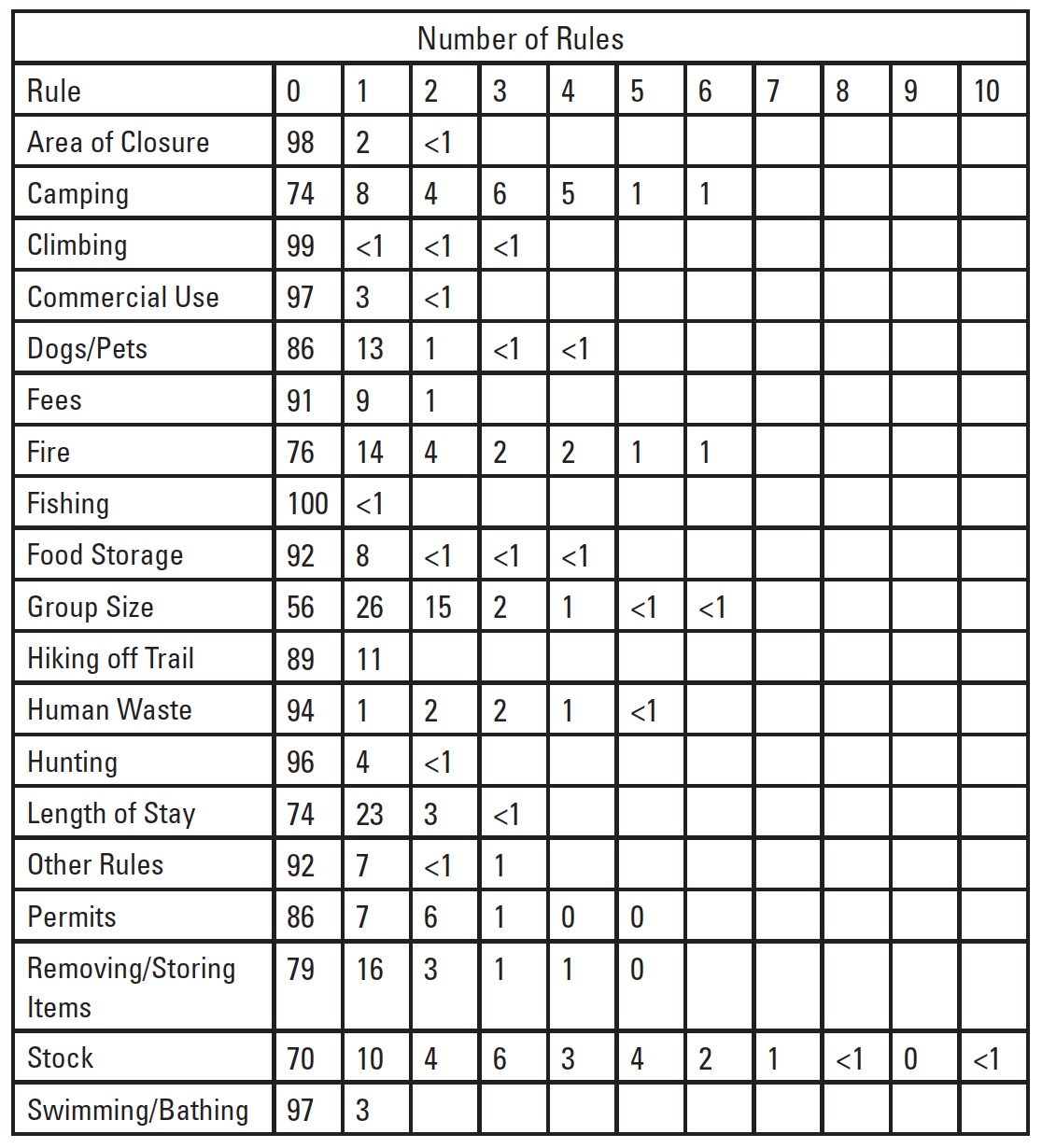

Table 1 shows the 19 categories of rules as well as the percentage of BLM and FS wildernesses that have rules. For example, 74% of the 669 wildernesses have no rules limiting length of stay, and 23% have one rule about length of stay.

Some of the more common rules are related to group size limits, stock rules, and length of stay. Group size limits were reported as limits on the number of people, the number of stock, or a combination of people and stock. More rarely, group size was limited by day use or overnight use, or rules more restrictive in some areas or during certain times of the year. Of the 297 wildernesses with group size limits, the most common rule was limiting the group size of people (n=255). The most common group size limit was 12 people (n=73) or 10 people (n=72). The most common stock size limit was 8, 12, and 25 stock, with 15 wildernesses having each of the size limits.

There were more kinds of stock rules than any other category. Stock rules were most often reported as limiting the proximity of stock to water, trails, and campsites; rules about hitching horses; and whether stock were allowed on trails. Of the 202 wildernesses with stock rules, the most common rule was a requirement for weed-free feed (n=117).

Length of stay rules were most often limits on the number of days at one location, one visit, or various other time periods. Of the 178 wildernesses with length of stay rules, the most common rule was limits on the length for a single visit (n=67). The most common limit was 14 days (n=58).

Camping and campfire rules were also common. Camping rules were most often limits on the proximity of campers to water bodies, trails, campsites, and other features, or much less commonly as rules about camping only in designated campsites or zones. Of the 173 wildernesses with camping rules, the most common rule was a setback from trails (n=83). Setbacks from water were also common. Campfire rules were most often setbacks (from water, trails, campsites, elevation). Of the 161 wildernesses with fire rules, the most common rule was that fires were prohibited in some areas (n=59) (this does not include above a certain elevation or distance from water or any other features). It is typically a specific area such as a high-use area. Setbacks from trails are also common (n=45), as are setbacks from water. Fire was prohibited in 28 wildernesses.

Discussion

Unconfined recreation is a complete absence of recreation-related rules in wilderness. In high-use areas, rules are necessary if educational efforts don’t work because managers must preserve other elements of wilderness character, such as naturalness or solitude. Based on the rules that are listed in the www.wilderness. net database, 75% of the BLM and 25% of the wildernesses managed by the FS have no rules. Rules are more prevalent in wildernesses managed by the FS than those managed by BLM for several possible reasons. First, there may be fewer rules in BLM wildernesses. Second, the BLM may not report all the rules that affect their wildernesses in the database. Griffin (2016) found this to be the case with FWS wildernesses where there are many more rules on the agency website then are captured in the database. These reasons may need to be tested by using another source to confirm that the information in the database is comprehensive – most likely against agency websites.

One of the challenges of looking only at the number of rules is that it ignores the severity of the rules, which is more important than just knowing the number a wilderness has. For example, a wilderness may ban camping and campfires, which are only two rules, but the severity of prohibiting a recreational activity is very high, and arguably has a bigger impact on visitors than a wilderness with four rules that each have a very low level of severity. Future research will examine the weighting of the rules, which would take into account the spatial or temporal extent of a rule as well as the intensity of the rule.

Some of the most common rules tend to affect few visitors. For example, group size limits of 10 and 12 are much bigger than the typical group size in wilderness (Dawson and Hendee 2009). Similarly, length of stay limits of 14 days affect few users as the average length of stay is several days (Dawson and Hendee 2009). Rules about camping and campfires are often setback distances from water. In and of itself, this does pose an undue hardship on recreational users, but unlike the length of stay and group size rules, camping and campfire rules affect many users, as many people like views of water and want to camp – and have fires – close to it. Stock rules, although common, affect only stock users as opposed to all visitors.

There were some areas where managers might want to revisit the rules for their wilderness. For example, given the problems associated with exotic species and horse manure as a major cause of their spread, some wildernesses do not require certified weed-free feed, although they have other rules affecting stock. Some rules seem challenging to enforce, such as no camping, fires, or grazing within a certain distance of a riparian area or a meadow. Other rules conflict with Leave No Trace recommendations, which are indirect means of influencing user behavior, whereas BLM and FS rules are a direct means of managing recreation. For example, LNT principles (2016) recommend camping 200 feet (61 m) from water, yet most camping regulations for the BLM and FS wilderness use 100 (30.5 m) feet as the distance.

Conclusions

This research was designed to investigate unconfined recreation in the 669 wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service. The www.wilderness.net database is an imperfect source of information, but it does at least provide a window into unconfined recreation in wilderness. Although there are rules that confine visitors recreating in wilderness, 41% of the wildernesses have no rules according to the information in the database. Assuming the database is a compre- hensive listing of rules, this research has shown that visitors seeking an unconfined recreational experience in wilderness are more likely to experience it in wildernesses managed by the BLM than the FS. However, the database does not capture all the rules that limit recreational activities in wilderness.

Table 1 – Percent of BLM and FS wilderness with recreation-related rules by category (n=669 wildernesses)

Managers should ensure that the rules in www.wilderness.net database are complete and accurate for each wilderness for several reasons. First, this central repository of rules makes it possible for researchers to gauge the state of unconfined recreation in the entire National Wilderness Preservation System. Second, some agency websites refer prospective wilderness visitors to the www.wilderness.net site to learn about the rules that may affect their recreational use of wilderness.

While knowing the number of rules a recreational visitor will encounter in wilderness is important, it is only the first step in this research. Future research will explore the weighing attached to the rules as well as developing an alternate weighting scheme to more fully capture the extent of unconfined recreation in wilderness

Acknowledgments

This research project benefited from some initial exploration of categorizing the rules from Misty Brooks, Angela Michael, and rest of the students in the fall 2015 wildland recreation management class in Grand Valley State University’s Biology Department.

C. “GRIFF” GRIFFIN is a professor of natural resources management at Grand Valley State University in Michigan; email: griffinc@gvsu.edu.

VIEW MORE CONTENT FROM THIS ISSUE

References

Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, USDA Forest Service, and US Geological Survey. 2014. 2020 Vision: Interagency Stewardship Priorities for America’s National Wilderness Preservation System. Washington, DC: Wilderness Policy Council.

Dawson, C. P., and J. C. Hendee. 2009. Wilderness Management: Stewardship and Protection of Resources and Values, 4th ed. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Griffin, C. B. 2016. Review of Wilderness Character Studies for Fish and Wildlife Service Wildernesses. Report to the Arthur Carhart Wilderness Training Center, Missoula, MT.