Soul of the Wilderness

December 2016 | Volume 22, Number 3

by CHAD P. DAWSON and VANCE G. MARTIN

Wilderness Leader

Dr. John C. Hendee, cofounder of the International Journal of Wilderness (IJW) in 1995 and longtime IJW editor and wilderness champion, died on June 16, 2016, in San Rafael, California, after a brief illness. John Hendee was a nationally known researcher, author, educator, and administrator related to forestry, human dimensions of natural resources, wilderness stewardship, visitor experiences in wilderness, and wildlife management in wilderness. Dr. Hendee was internationally known for the integration of science-based information with wilderness management and decision making, his books and articles on wilderness management and stewardship, and his efforts to establish IJW as a journal and forum to keep wilderness professionals informed, sharing best-practices and strengthening the importance of them worldwide.

The following brief narrative about John’s life cannot begin to illustrate the complexity of his many and diverse accomplishments in a very full life in public service, research, education, and activism.

Forest Harvesting to Wilderness Experiences

John Hendee was born in 1938 in Duluth, Minnesota, nearby to where his father worked with the US Forest Service (USFS). Clare Hendee, John’s father, had a long and distinguished career with the USFS culminating as deputy chief, and was the person that John often mentioned as his professional model. After John had served 25 years with the USFS himself, and with one of his daughters and son also working in their early careers in the USFS, he would jokingly refer to the USFS as “the family business.”

John earned his BS degree in forestry from Michigan State University (1960) and began his career in 1961 in reforestation, timber sale management, and road construction on the Siuslaw National Forest in Oregon. John continued work with the USFS as he did his graduate work, completing a master’s degree from Oregon State University (1962) and later a PhD degree from the University of Washington (1967). During those years he was involved with backcountry activities with his family and with Boy Scout groups in places such as in Oregon, where he would take boys into backcountry areas that would later be part of the National Wilderness Preservation System. During his doctoral program and as a USFS employee, he spent a year in Washington, D.C., working as a legislative affairs intern for Senator Frank Church and Congressman Jim Weaver, focusing on wilderness legislation and designations.

John worked for the US Forest Service for 25 years (1961–85) in field forestry, research, legislative affairs, and administration. He received numerous awards during his career, and the one that he said meant the most to him was a Lifetime Leadership Award given to him at the 9th World Wilderness Congress in Merida, Mexico (2009) by the US Forest Service for his educational work in wilderness management and stewardship.

In those 25 years with the USFS, John came to see the values and benefits of all the national forest outputs, from timber to wilderness experiences. Some of those insights came from trips as a young man with his father to backcountry areas such as the High Sierras in California. During an interview on May 6, 2014, John mentioned that another important turning point later in his life was attending a wilderness gather-ing where he learned how “to take people on a wilderness vision quest, [as] a time in the wilderness alone … that introduced me to the healing and personal growth side of wilderness.” Through his early research about wilderness experiences, and in his later support of his wife Marilyn’s guiding business that took people into wilderness on vision quests, John would explore the positive and personally transformational impacts of wilderness experiences on visitors to wilderness and wild places.

Wilderness Researcher and Educator

In 1985, John left the USFS and joined academic colleagues in a different career as an administrator, researcher, and educator related to forestry, recreation, and wilderness management. He served in various positions at the University of Idaho as Dean of the College of Forestry, Wildlife and Range Sciences (1985–1994), Professor of Resource Recreation and Tourism, and Director of the Wilderness Research Center (1994–2002).

His academic career extended his writing efforts in research and educational materials that had begun with numerous research reports during his USFS career. During his life he authored or coauthored more than 150 professional publications, including contributing chapters to 18 books and coauthoring three textbooks – two of which are still in print. His most well-known publication, used extensively nationally and internationally as the standard text, is Wilderness Management: Stewardship and Protection of Resources and Values. Now in its fourth edition (Dawson and Hendee 2009), it was first published in 1978 as a result of USFS collaboration and an interest in federal interagency training for wilderness managers. To assure timely, cost-effective updates, John engineered the donation of publishing rights of this textbook to The WILD Foundation, which has been responsible for three subsequent editions.

Contributing to the fifth edition of Introduction to Forests and Renewable Resources was a special achievement for John, as his father, Clare Hendee, was previously a co-author of this book. John would go on to contribute to and then lead the subsequent editions of that textbook through the current eighth edition (Hendee, Dawson, and Sharpe 2012).

One of the most ambitious projects John contributed to was his work as cofounder of the International Journal of Wilderness in 1995 and serving as its managing editor and later editor in chief for 16 years. IJW is one of the longest ongoing outreach projects of The WILD Foundation, and the only international journal dedicated to wilderness with an unparalleled online archive.

The WILD Foundation and the World Wilderness Congress (WWC)

John served on numerous boards of directors over his career, including nearly 30 years with The WILD Foundation, working for the protection of wildlands and natural areas worldwide. His contribution and leadership focused on promoting wilderness research and science-based stewardship and management of wild lands to support The WILD Foundation’s global commitment to wildland and wildlife protection, as well as their World Wilderness Congresses (WWC), which convenes periodically around the world.

He first became acquainted with The WILD Foundation via discussions with Vance Martin regarding John’s potential presentation in 1983 at the 3rd WWC in Scotland. The USFS would first reject and later approve John’s request to travel to WWC3 to make a presentation, where he then personally met Ian Player and Vance Martin. The friendship with Vance and Ian would lead John into an international wilderness movement – through WILD and the WWC – that would become one of John’s most committed wilderness organization relationships.

Hendee the Mentor

I often credit John Hendee as my very first source of knowledge about the National Wilderness Preservation System and igniting a career-long craving to contribute to the science of wilderness. Fresh out of the military, studying parks and recreation administration at a community college in 1974, the instructor assigned an article for us to read by John Hendee and Bob Lucas, published in 1973 in the Journal of Forestry, entitled “Mandatory Wilderness Permits: A Necessary Management Tool.” As I’ve repeated so many times in my life, that article and the rejoinder by Behan in 1974 got this college student’s attention and has never let go. Behan’s suggestion that mandatory permits represented a “police state wilderness” resonated just as strongly with this reader as Hendee and Lucas’s plea for use of permits as a way to educate visitors, understand visitor use and users better, and potentially control impacts through limits on use. The complexity of protecting the wilderness character of these places, assuring wilderness experiences for visitors, and meeting the purpose of wilderness for all people and future generations was a dilemma in trade-offs we still struggle with; these pioneer wilderness scientists educated us so well.

I didn’t know it then, but that youthful image of John Hendee published along with that article represented my greatest mentor down the road for many years, first as a graduate student at Virginia Tech, later as a university faculty member in Georgia, and eventually as a Forest Service wilderness scientist in Montana. John was the calm hand that gave me a nudge in the right direction when I questioned the right way to go, the calming voice when I struggled with bureaucracy or criticism, the strength in resolve when I needed a critical analysis of a decision, and, most of all, a mentor in integrity and open-mindedness toward fellow human beings. He taught me so much. I will be forever grateful.

ALAN WATSON is the senior research scientist at the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, Missoula, MT.

Figure 2 – John loved to travel in desert wilderness areas of the southwestern United States and especially southern California. Here he is in the North Maricopa Wilderness studying some cactus species while on a field trip with Bureau of Land Management staff in Arizona. Photo by Chad Dawson.

Chad Dawson: My Personal Experience with John Hendee

While I had read many articles by John and the first and second editions of the Wilderness Management textbook, my first personal meeting with John was at the 5th World Wilderness Congress in 1993 at Tromso, Norway. He, his son Jared, and a group of graduate students were staying at the same camping resort in the hills outside the city as was the group of colleagues I was traveling with – all of us making presentations at the WWC. Through our informal conversations and my questioning him about his wilderness visitor research, I came to understand that the reason he was so prolific in writing and publishing was because his reasoned arguments for visitor management and resource protection were well supported by research. After a few in depth conversations, I was immensely impressed with how informed, organized, and passionate he was on numerous and diverse topics about wilderness.

A couple of years later, when I was teaching a class at State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry using the Wilderness Management textbook (2nd ed.), I explained in lecture that some of the material on visitor participation in wilderness was outdated, and that visitor use had actually increased and not decreased as projected in one of the book chapters. After I showed some of the newer information to the class, one of the students asked: “If [I] know the book author, and did [I] plan to bring that new information to his attention?” The class got into a discussion about visitor participation, and the student’s question to me was put aside. In the following class, I explained that because the actual visitor use had increased it changed some of the implications for wilderness management as stated in the book, and so I began to outline the newer implications. The same student, who had asked me previously if I knew the book author, interrupted and asked again: “Have you contacted the author yet to share some of the newer visitor information”? I confessed that I had not, but added that I would do so by email that very afternoon.

My email to John was quickly answered by his invitation to me to submit a proposed outline for an updated chapter with supporting references because he was starting to plan for a third edition of the book. I provided the requested outline and quickly received an email to this effect: “Congratulations, you are now coauthor of the revised chapter. How soon can you provide a full draft of that chapter?” The class was delighted to hear that the book author, John Hendee, was interested in updating the book and they began to read it more thoroughly. As I presented each chapter through the semester and the class discussed the new material that should be considered in a book revision, the same student challenged me to communicate the ideas to John. Following each email to John with an outline of proposed chapter changes, I would receive back an email that saying, “Congratulations, you are now coauthor of this additional proposed chapter revision. How soon can you provide a full draft of the additional chapter?” As the semester came to an end, I began to worry about what I had gotten myself into with all these proposed revisions. That was about the time that I received another brief email from John: “Congratulations, you are now a coauthor of the entire proposed third edition. Can you meet me at an upcoming wilderness conference to set a two-year work plan together?” I was flabbergasted – how was I going to keep up with this hard-driving colleague?

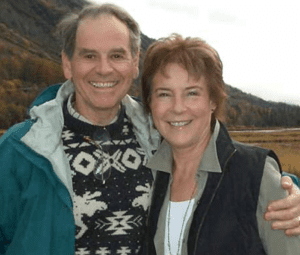

Figure 3 – John and Marilyn Hendee on a field trip near Homer, Alaska, following the 8th World

Wilderness Congress in Anchorage. John attended eight WWCs during his affiliation with Vance Martin and The WILD Foundation. Photo by Chad Dawson.

The Hendee Influence

John Hendee and I began our careers in the same general era, which, let us just say, was a number of years ago. John, like many of us who worked in USFS social science during those early years, had many interests. All hovered around forest, recreation, and wilderness management social science. John believed studies of users, managers, youth, and other subsets of the American population were essential for improving management philosophy and practice. I had the privilege of knowing and working with John Hendee since beginning my career. John had a very strong influence with managers, researchers, and politicians. His research, writing, and professional involvements are still referenced. One of a number of experiences I had with John was to participate in a wilderness vision quest that he and a colleague had organized in North Carolina. Most of the participants were in research with the USFS’s Southern Research Station. There were different “takes” on the quest by those of us who participated. One of my takes was that John had, and likely still has, a deep spiritual connection to wilderness. John excelled at leadership through his innovative ideas, guidance, encouragement, accomplishment, and eagerness. Along with others, his wilderness leadership is evident in the success of The WILD Foundation, the World Wilderness Congresses, and the IJW. I still struggle to fully realize that John Hendee has moved on to his ultimate wilderness vision quest. Good job, John!

KEN CORDELL is a scientist emeritus from the USDA Forest Service.

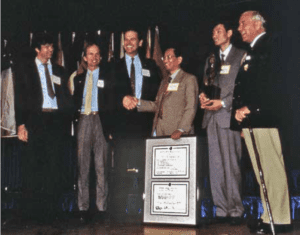

Figure 4 – At the 4th World Wilderness Congress (Colorado), recognizing China’s massive re-afforestation work to combat desertification by presenting them with the first Green Leaf Award (from WILD Foundation). From left: Jonathan Bronson, Vance G. Martin, John Hendee, representatives from Embassy in the USA of the People’s Republic of China, and Ian Player. Photo by The WILD Foundation©.

Over the next two years of collaboration with John on the third edition of the Wilderness Management textbook, I came to know him as a relentless and extremely talented science editor with some chapters undergoing up to 14 detailed revisions before being considered final. Some days I wondered if he could ever be satisfied with what we were doing, and then I took the time to compare some of the early chapter revisions with the later versions, and I learned two important lessons: (1) the chapters were decidedly improved and so was the integration between chapters resulting in an easier-to-read book for students, and (2) not only was I becoming a much better writer, I was learning to edit and was sending back revisions to John on some of his work. I do not recall when that editing “give and take” began, but I must have earned his respect because he began to accept my suggested editing to his writing.

Over the years that followed, we revised the Wilderness Management textbook in a fourth edition, the renewable resources textbook in an eighth edition, and other articles and publications on wilderness and wilderness experience programs. John as editor in chief of the International Journal of Wilderness invited me to become managing editor of IJW, and he mentored me along each step of the way. I have never had another colleague like him. If he promised some writing or editing by a certain date, it was done well and on time. He set and held extremely high professional standards for himself – he expected no less from me. When the work became intense or seemed overwhelming, he always had an anecdote from USFS days, a humorous story from his years in academia, or an observation about the contradictions in human behavior. He could tell a good story and enjoyed hearing them as well. As driven as he was to be highly productive at integrating wilderness research into wilderness management decision making and stewardship, he was a gentle zealot in his approach to engaging folks in wilderness experiences. He extolled the healing, personal development, and self-reflection experiences of wilderness to any and all who would listen and he regularly visited wilderness him-self, with his wife Marilyn, and with other friends and colleagues.

Now John is in the far country with the creator of wild places. I hope he is at peace on a ridge over-looking a grand mountain landscape – the kind of place he liked to protect and to find on his wilderness hikes to reflect on life.

Vance Martin: My Personal Experience with John Hendee

Life’s course is designed through personal relationships, many of them often unusual … “strange bedfellows” are not uncommon. Such is the case with how John Hendee came into his work with WILD and the WWC.

In the early 1970s, Ray Arnett was the head of California Fish and Game Commission under Governor Reagan, and as such represented his state and the hunting community in general when he was a delegate to the 1st World Wilderness Congress (South Africa 1977). An ardent political conservative and hunter, he became fast friends with Ian Player (a progressive changemaker and former hunter), and they stayed in touch closely. When Ronald Reagan was elected US president, he named Arnett his Assistant Secretary for Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, under Secretary of Interior James Watt.

At that time, John Crowell was President Reagan’s Assistant Secretary of Agriculture. He decided to visit South Africa, and Ray Arnett advised him to go on a wilderness “trail” with Ian Player. In 1982, the two men went, alone, into the iMfolozi wilderness for four days, and Crowell was incredibly impressed. He asked Ian if there was anything he needed done in Washington.

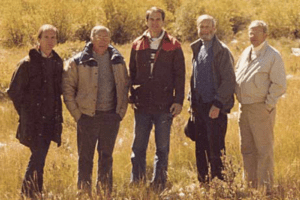

Figure 5 – Members of the Executive Committee, 4th World Wilderness Congress during a break in the 1985 planning meeting at Rocky Mountain National Park. From left: Vance G. Martin, Jay Hughes, John Hendee, Ed Wayburn, and Tom Thomas. Not pictured are Michael Sweatman and Peter Thacher.

Photo by The WILD Foundation©.

Ian had heard of John Hendee (political liberal and visionary), who had virtually pioneered the academic field of “the use of wilderness for personal growth and therapy,” with at least 30 peer-reviewed papers on the subject by 1980. Ian asked Crowell, whose Department of Agriculture had responsibility for the USFS, if he could arrange for John Hendee to participate in the 3rd WWC. Crow-ell not only did that, he also advised the secretary of agriculture (John Block) to be a keynote speaker at the 3rd WWC.

At that time, John Hendee was at the USFS Southeast Forest Experiment Station. Internet, email, and fax were not yet invented(!) so we talked often over expensive telephone calls, and I learned quickly that he was a Type A executive – a thinker, visionary, and hardworking leader with prodigious output. By the time John arrived in Scotland, we had become friends, and that friendship grew during the WWC. I learned a great deal by watching him operate. As the 3rd WWC proceeded, John Hendee and Ian also formed a strong friendship, and John told Ian that the WWC must come next to America and that he was prepared to help. Ian said he had just the young man to run it, and they both conspired to convince me that my future lay in the United States.

Ian Player had been “working on me” for a year, insisting that it was time I stopped living abroad and return to the States, to “be the American you are.” In 1974 he had created the International Wilderness Leadership Foundation (IWLF) – a US nonprofit organization. It operated for some years with initial funding Ian raised, with a very influential board and a mandate to not only collaborate on the World Wilderness Congress but also to take young people out on wilderness trail with Ian’s Wilderness Leadership School in South Africa – which it did thru a program with the US Explorer Scouts. It had slowed down its programs, and Ian wanted me to revive it. (I eventually did so, with John’s help, in the process rebranding it as The WILD Foundation.)

By the end of the 3rd WWC, I agreed to do a site selection trip to the States, and John set up meetings with several universities that could arrange for sponsored offices, some support, and so forth. John traveled with us for most of that trip, on government funding (“international relations”), and we visited sites in California, Oregon, and Colorado. By the end of that trip, with a commitment from Colorado State University to provide offices and with the basic financial help of newspaper publisher Tom Worrell, we could take the next step. I moved my family from Scotland to Colorado, and we started the daunting task of organizing the 4th WWC.

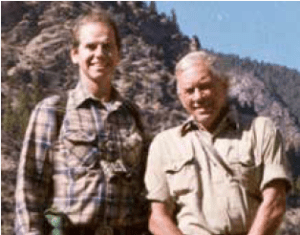

Figure 6 – John Hendee (left) and Ian Player on

a hike at Taylor Ranch (University of Idaho) in

1987 following the globally successful 4th World

Wilderness Congress. Photo by Vance G. Martin©.

John Hendee was incredibly committed to this process. Although he was still a leader in the USFS, he was literally on the phone to me every day, mentoring, coaching, and envisioning with me whatever we needed to do. John also saw that science needed to be fully represented in the international wilderness movement and that the WWC was the means to do this. It was his vision that started the Science Program that premiered in 1987 at the 4th WWC. With eight concurrent sessions it was very rigorous, with many practical outputs including (inter alia) the first promotion and intense research into the concept of marine wilderness. That Congress was pivotal in global conservation and in positioning the wilderness concept internationally, with Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland chairing the only US hearing on her UN-sponsored initiative (the Bruntland Report, which popularized the concept of sustainable development), with participation by 17 ministers of finance or environment, opened by President Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of Treasury (James Baker), and chaired by Maurice Strong (chair of the first UN Conference on Sustainable Development that established UNEP). Out of the 4th WWC came many things, among them the first inventory of global wilderness (by Michael McCloskey, CEO and chairman of the Sierra Club) and the working concept of a World Conservation Bank (conceived by WILD chairman and former banker Michael Sweatman), which eventually became the Global Environmental Facility of the World Bank (GEF) and has since granted over USD 20 billion to environment and biodiversity projects worldwide.

John Hendee was responsible for helping me steer this global ship, and stood by me daily for many years. Even when he left the USFS and became dean at the University of Idaho, we stayed closely in touch daily, visiting and traveling frequently, with visioning sessions in the wilderness and agendas in Washington D.C., and elsewhere. The 4th WWC was a significant milestone in international conservation and greatly helped establish wilderness as an important global concept.

After the 4th WWC, John remained a key adviser, mentor, and visionary who guided my career. As is always the trajectory between teacher and student, we were constant col-leagues. We almost always agreed on tactics and strategy, but when we did not – to the credit of John’s vision, person, and style – we always remained fast friends and colleagues, sharing strategy, black humor, beers, and ideas. He was instrumental in my work and in creating wilderness as a core concept in international conservation and sustainability. I greatly miss his daily presence and wisdom.

Lifelong Wilderness Experiences

John always spoke fondly of his early backcountry experiences with his father in various places he was stationed with the USFS. He credited a trip with his father in the High Sierras in 1953 as being a turning point in his view of wilderness and wild places. As a young professional, John would lead Boy Scouts in his time with the USFS in Oregon into the backcountry – and some of those places would later become designated wilderness areas. As a father, John enjoyed taking his family on wilderness trips in the summer around the United States. Later in life, John and his wife, Marilyn, loved hiking and camping in the wilderness, especially the desert, and they spent many days and nights of their life together in beloved places in the eastern Sierras and Mojave Desert.

The positive power of wilderness experiences was often the subject of John’s research or his stories of personal adventures. As he noted during his interview in 2014: “Even people who have not been to wilderness … go out and they come back feeling they have been in touch with a part of themselves that they had not touched before.”

CHAD P. DAWSON is editor in chief of IJW and professor emeritus from SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse NY; email: chad@wild.org.

VANCE G. MARTIN is president of the WILD Foundation based in the United-States, Chairman of the Wilderness Specialist Group (WCPA/IUCN) and international director of the World Wilderness Congresses and their legacy of generating important national and global conservation initiatives; email: vance@wild.org.

VIEW MORE CONTENT FROM THIS ISSUE

References

Dawson, Chad P., and John C. Hendee. 2009. Wilderness Management: Stewardship and Protection of Resources and Values, 4th ed. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Hendee, J. C. 2014. Interviewed May 6, 2014. © Films by Fulcrum for the Conversations on Conservation series (2016). Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Hendee, J. C., C. P. Dawson, and W. F. Sharpe. 2012. Introduction to Forests and Renewable Resources, 8th ed. Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL.