Stewardship

August 2015 | Volume 21, Number 2

BY PETER R. PETTENGILL

Regardless of its official wilderness designation, Grand Canyon National Park is arguably one of the most iconic wild places in the National Park System. It has drawn more than 4 million visitors a year since 1992, but its backcountry remains a bastion of solitude. As the second century of the U.S. National Park System approaches, park managers at Grand Canyon will have to weigh the importance of preserving solitude in light of contemporary policies aimed at engaging a growing and increasingly diverse population. Wrestling with the relevancy of solitude promises to be at the heart of this issue.

The Importance of Solitude at Grand Canyon

Decades of research demonstrate that solitude, one of the five qualities of wilderness character, is an important motivation among visitors to Grand Canyon’s backcountry (Towler 1977; Underhill et al. 1986; Stewart 1997; Backlund et al. 2006). A questionnaire administered to Grand Canyon backcountry users in 1977 found that 96% of respondents considered the opportunity “to get away from the sights, sounds, and smells of civilization” to be either “fairly” or “very important” to their trip (Towler 1977). A similar study conducted nearly a decade later found that 90% of respondents placed some degree of importance on “being alone” during their trip (Underhill et al. 1986). Yet another questionnaire, conducted 10 years later, used open-ended questions to allow visitors to describe the “high point” of their trip. Responses included phrases such as being “away from the world,” “away from other people,” and “away from civilization” (Stewart 1997). Finally, a recent study of backcountry day hikers noted “solitude” as being an important motivation for 87% of respondents (Backlund et al. 2006). Clearly, solitude is relevant to the backcountry experience at Grand Canyon National Park.

Grand Canyon National Park’s Proposed, Potential, and Not Wilderness

Approximately 1,143,918 acres (462,927 ha) (94%) of Grand Canyon National Park is proposed wilderness. Of that, 1,117,457 acres (452,218 ha) is recommended for immediate wilderness designation and 26,461 acres (63,386 ha) is recommended for designation as potential wilderness. Therefore, these lands are managed as wilderness as guided by National Park Service (NPS) policy (USDI National Park Service 2006). This includes providing opportunities for solitude as directed by the Wilderness Act of 1964 (Public Law 88-577 1964). However, regardless of visitor motivations for recreation, the park’s Corridor management zone has not been recommended for immediate or even potential wilderness designation.

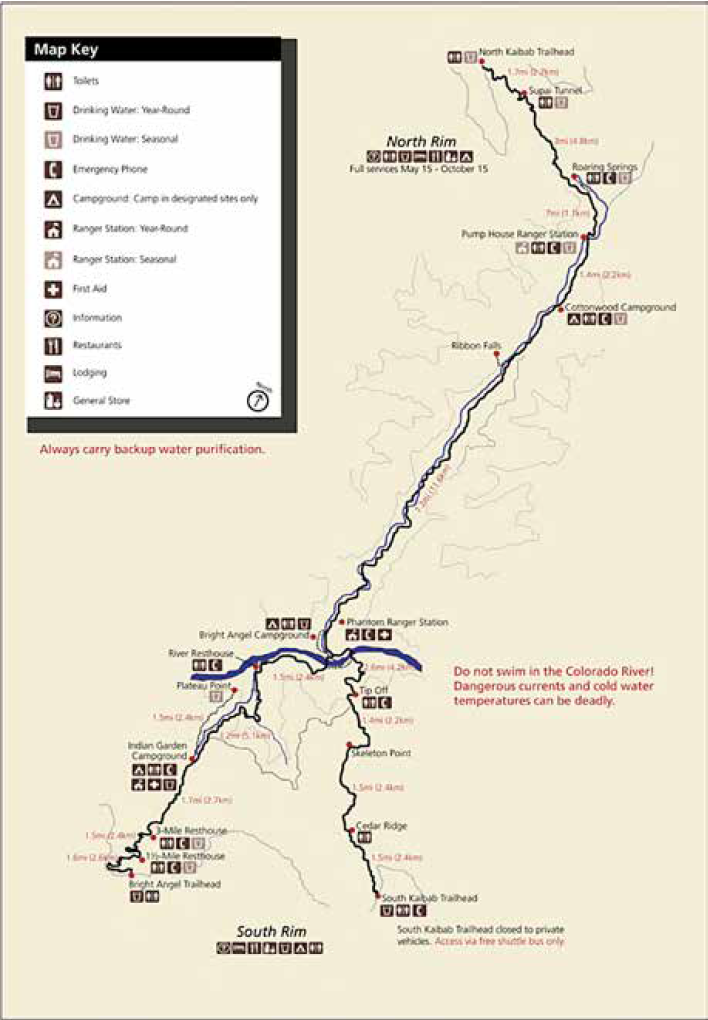

The Corridor is one of four backcountry management zones within Grand Canyon National Park (Figure 1). It offers the most developed backcountry recreation opportunities, including the Bright Angel and North and South Kaibab Trails; Cottonwood, Bright Angel, and Indian Garden developed campgrounds; Phantom Ranch tourist lodging; ranger stations; and sewage and water treatment facilities. These amenities increase access to the backcountry and support its largest levels of overnight visitation (57% of overnight backcountry use in 2012). While overnight use levels in the Corridor have long been measured, monitored, and managed through an active permit system, day use has remained unconfined by regulation.

Corridor Management Policy

Grand Canyon National Park’s 1995 General Management Plan (GMP) promised to “maintain the opportunity for threshold wilderness experiences” along Corridor trails (USDI National Park Service 1995, p. 36), implying that while the Corridor may not be wilderness it should provide a transition zone or gateway to them. It also stated that use levels are a critical element of visitor experiences and instructed that an active monitoring program, along with indicators and standards, be established to determine visitor carrying capacities on Corridor trails. Furthermore, the GMP directed that “measures may be taken under the Backcountry Management Plan if carrying capacities are exceeded” (ibid., p. 58), and suggested “the possibility of day use permits or other restrictions” (ibid., p. 60).

The park’s 1988 Backcountry Management Plan (BMP) implicitly established indicators and standards for visitor carrying capacities. Indicators have been described as measurable, manageable variables that help define the quality of parks and outdoor recreation areas and opportunities, and standards define the minimum acceptable condition of indicator variables (Manning 2007). One example of an indicator from Grand Canyon’s BMP is the “number of daytime contacts with other people” (Backcountry Management Plan 1988, p. 37). This indicator serves as a proxy for solitude, and standards for it were developed for each backcountry management zone.

Various standards for encounters with other overnight groups, day hikers, and river users were distinguished across backcountry management zones, although some were more specific than others. As an example, a standard of “one or fewer contacts with other overnight parties or groups per day” was established for Grand Canyon’s Wild Management Zone. As noted earlier, the park consists of four backcountry management zones. These zones provide a range of recreation opportunities, with the Corridor being the most developed and accommodating the highest levels of use, while the Wild Management Zone is largely undisturbed, natural processes predominate, and outstanding opportunities for solitude exist. Standards for contacts with day hikers and rivers users in the Wild Manage-ment zone were vague and described as “probably no contact with day hikers” and “potential contact with many river users in some areas.” Furthermore, other than overnight campground capacities, the 1988 BMP did not prescribe any explicit numeric standard for the Corridor Management Zone. In its case, the minimum acceptable condition for daytime contacts with other people is “large numbers” and does not distinguish between user types. This leaves management of visitor use levels in the Corridor largely under NPS discretion.

Addressing Issues and Assessing Use Levels

On August 27, 2014, Grand Canyon National Park issued a news release announcing an interim Special Use Permit system for organized, noncommercial groups conducting rim-to-rim extended day hikes and runs (information regarding details of the interim policy is available at www.nps.gov/grca/learn/news/interim-permits-r2r.htm). This action was the result of a number of issues associated with increasing use of Corridor trails, including resource impacts, overburdened facilities, mounting pressures on search and rescue operations, and issues related to user conflict and crowding. Each of these issues has been documented by park staff and corroborated by visitor comments in recent years. Furthermore, public scoping for the park’s revised Backcountry Management Plan held in 2011 emphasized many of these same concerns. These emerging issues related to increasing visitation led park staff to begin a pilot study to help measure use levels along Corridor trails in 2013.

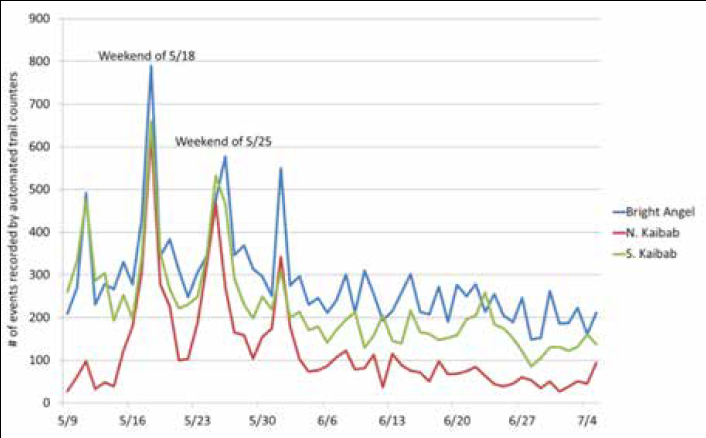

Automated trail counters were established several miles beyond the trailheads of the Bright Angel, North, and South Kaibab trails to help estimate use levels. This data, combined with overnight backcountry permit data, allowed park staff to begin assessing use levels and patterns of visitors hiking or running to the Colorado River and back, or across the canyon (rim-to-rim), in a single day. Data from each of the auto-mated trail counters is illustrated in Figure 2. It is important to note that the data from this figure describes the number of events as recorded by each automated trail counter. It is not adjusted to account for back-and-forth travel by individual visitors.

Perhaps more important than the levels of use illustrated in Figure 2 is the pattern it reveals. Peak use periods occur on a handful of weekends in the spring. These high use levels likely correspond to and exacerbate many of the issues described above, but the frequency of these high use periods is intermittent and predictable (e.g., weekends in May) (Figure 3).

Solitude Lost in Light of Contemporary Policy and Current Trends

The NPS estimates up to 800 people are traveling in the inner canyon during peak weekend days in spring and fall. Of that, 400 to 600 people are hiking or running rim-to-rim in a given day. It is hard to imagine that anyone could experience solitude or even have a “threshold wilderness” experience given these conditions. Undoubtedly, solitude is lost in the Corridor over weekends in the spring and fall. However, what are the potential benefits of accommodating this use?

With the coming of the second century of the U.S. National Park System drawing near, the National Park Service established “A Call to Action” to guide park planning and management in future years. Some of the primary mandates of this call are to “expand the use of parks as places for healthy outdoor recreation that contributes to people’s physical, mental, and social well-being,” and “welcome and engage diverse communities through … experiences that are accessible to all” (U.S. Department of the Interior 2011, p. 9). In light of this guidance, the stark challenge of managing solitude in the Corridor may become a resounding opportunity to act.

In 2013, the Outdoor Foundation reported that “running, including jogging and trail running, was the most popular outdoor activity with more than 53 million participants and a participation rate of 19 percent” (Outdoor Foundation 2013, p. 7). Running is also described as a “gateway” to other types of out-door recreation (ibid., p. 26) and is the favorite form of recreation for all racial and ethnic groups researched in the study, including African Americans, Asian/Pacific Islanders, Caucasians, and Hispanics (ibid., p. 48). Clearly, introducing visitors to Grand Canyon through extended day use, including trail running, is in keeping with the call to action.

It is also clear that wilderness, including proposed wilderness, be managed to provide opportunities for solitude (Public Law 88-577 1964; USDI National Park Service 2006). So, is there an inherent conflict between the call to action and long-standing legislation? How might park managers expand the use of parks as places for healthy outdoor recreation while simultaneously introducing the next generation of wilderness stewards to its enduring resources? Contemplating this conflict between access and preservation is more than a contemporary issue.

Figure 3 – A typical scene on a peak weekend (approx. 12

miles/19.3 km into the Corridor’s backcountry). Photo by Peter

Pettengill.

Wrestling with Solitude and Relevancy

The National Park Service Organic Act of 1916 is frequently cited as a dual mandate. Nearly 100 years ago it set in motion a mission “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for enjoyment of the same in such manner as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” Indeed, it often seems at odds with itself when society frequently associates access with enjoyment and use with inherent impacts to resources. And yet, the national parks have thrived during the last century. Not through a constant conflict within the mission but rather through a thoughtful and creative balancing of the act. This legacy of planning and management should continue in the future. As stated in the National Parks Second Century Commission Report, “To fulfill its mission in the next hundred years, the National Park Service must cultivate both strength of purpose and flexibility of approach” (National Parks Conservation Association 2009, p. 22).

Undoubtedly, a strong purpose of our parks is to protect resources; this includes a commitment to preserving solitude, a key feature of wilderness character. This strength of purpose has been cultivated over the last century. However, solitude is likely best served by a society that finds it relevant; relevant in an increasingly urbanized world and relevant as part of healthy outdoor recreation that includes rejuvenation of mind, body, and spirit. Facilitating opportunities for park visitors to not only access park trails but also experience solitude will help maintain its relevance and serve its long-term protection. So, what flexible approaches may be available to continue facilitating these opportunities?

A Gateway to Solitude

Trails in the Corridor management zone provide the most accessible means of experiencing the canyon’s grandeur from below the rim. Furthermore, in keeping with a vision for The Future of America’s National Parks they are quintessential examples of “superior recreational destinations where visitors have fun, explore nature and history, find inspiration, and improve health and wellness” (Kempthorne 2007, p. 13). While the next generation of wilderness stewards’ first exposure to Grand Canyon National Park’s backcountry may be sharing Corridor trails with hundreds of others on a weekend in spring, it may also provide inspiration to return. Solitude is an enduring resource of wilderness, but Grand Canyon’s Corridor is not wilderness. It can, and often does, however, serve as a gateway to wilderness. Day hikers may return to travel trails on less busy days. They may even find themselves contemplating an overnight stay at Phantom Ranch or planning a backpacking trip that includes Cottonwood, Bright Angel, and Indian Garden camp-grounds. Eventually, return visitors may even apply for a backcountry permit in Grand Canyon’s proposed wilderness, knowing that the promise of pristine nature and unadulterated solitude is worth the wait.

While the gateway to wilderness described above depicts an idyllic introduction to solitude, it assumes that high use periods on Corridor trails will remain concentrated on a handful of weekends a year. But what if that is not the case? What if use on weekdays begins to resemble that of weekends as visitors seeking solitude begin to understand these use patterns? Furthermore, should visitors seeking solitude during spring months be sanctioned to weekdays for their desired experience?

Many of the issues managers face at Grand Canyon National Park may be addressed through outreach and education: information regarding Leave No Trace principles to reduce resource impacts; information regarding how to Hike Smart (www.nps. gov/grca/planyourvisit/hike-smart. htm) to reduce pressures on search and rescue operations; and information on Trail Courtesy (www.nps. gov/grca/planyourvisit/courtesy.htm) to minimize user conflict. But issues of crowding and loss of solitude may require setting capacities and developing a day-use permit system.

Grand Canyon National Park’s GMP specifically notes the implementation of day-use permits as one management action that could address carrying capacities being exceeded. Yet, carrying capacities for day use have not been established. Furthermore, in light of contemporary policy and acknowledging that perceptions of solitude may vary, one may question the value of a single carrying capacity for the Corridor. Current use patterns demonstrate that the highest demand for recreation on Corridor trails occurs on weekends in the spring and fall. Common sense dictates that summer temperatures may warrant no day hiking in the inner canyon at all (average high temperature is over 100° F/38° C, June through August). And, inclement weather and icy trail conditions may be enough to maintain opportunities for solitude throughout winter months. But, are the climactic conditions of the canyon enough to preserve diverse recreation opportunities?

Conclusion

Grand Canyon National Park’s Corridor management zone provides a diverse range of opportunities within a single setting. It accommodates stock users, day hikers, backpackers, and trail runners. Its facilities support high levels of use during peak seasons, but one can still find relative solitude within its bounds throughout much of the year. Furthermore, with each season comes an ebb and flow of visitation, allowing backcountry users to experience a social setting best suited to their desires. This diversity should remain and become more deliberate.

A day-use permit system implemented during spring and fall months would provide flexibility and strengthen the diversity of opportunities in the Corridor. Management of the Corridor need not fall into the trap of either/or but rather provide both high levels of access and opportunities for relative solitude. This could be achieved through variable use limits rather than a single capacity. A standardized capacity may lead to a homogenized experience as demand potentially increases and balloons into traditionally lower use periods. Variable use limits, based on current conditions and sound professional judgment, would not only preserve diverse opportunities in the Corridor but also maximize access to healthy recreation while maintaining opportunities for relative solitude.

The National Park Service piloted a visitor use study to help measure use levels on Corridor trails in 2013. It has allowed park managers to not only identify peak periods of use but also to acknowledge the wide range of use levels over the course of a year. Currently, accommodating high use on a handful of weekends in the spring and fall may serve solitude best by introducing multitudes to intermittent moments of peace and quiet below the rim. But, as these visitors return seeking more, the onus will be on park man-agers to continue to provide it. It is clear that managers are mandated to preserve solitude in proposed wilderness. However, it should not be unreasonable for visitors to expect relative solitude throughout much of the year, even in the Corridor.

Grand Canyon National Park is currently in the process of revising its Backcountry Management Plan. For more information regarding the planning process and how you can be involved, please visit http://www. nps.gov/grca/parkmgmt/bmp.htm.

PETER R. PETTENGILL is an assistant professor of environmental studies at St. Lawrence University in Canton, NY. He was formerly an outdoor recreation planner stationed at Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona; email: ppettengill@stlawu.edu.

VIEW MORE CONTENT FROM THIS ISSUE

References

Backlund, E., W. Stewart, and Z. Schwartz. 2006. Backcountry Day Hikers at Grand Canyon National Park. Urbana: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Kempthorne, D. 2007. The Future of America’s National Parks: A Report to the President of the United States by the Secretary of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne. Retrieved from http://www.nps.gov/foda/learn/management/upload/FutureofAmericaNa-tionalParksFINAL.pdf.

Manning, R. 2007. Parks and Carrying Capacity: Commons without Tragedy. Washington, DC: Island Press.

National Parks Conservation Association. 2009. Advancing the National Park Idea: National Parks Second Century Commission Report. Retrieved from http://www.npca.org/assets/pdf/Commission_Report.PDF.

Outdoor Foundation. 2013. Outdoor Participation Report. Retrieved from https://outdoorindustry.org/images/researchfiles/ParticipationStudy2013.pdf?193.

Stewart, W. 1997. Grand Canyon Overnight Backcountry Visitor Study: Use of Diary-like Techniques. Report submitted to Grand Canyon National Park, Grand Canyon, AZ.

Towler, W. 1977. Hiker perception of wilderness: A Study of social carrying capacity of Grand Canyon. M.S. thesis, University of Arizona.

Underhill, H., W. Stewart, R. Manning, and E. Carpenter. 1986. A Sociological Study of Backcountry Users at Grand Canyon National Park. Technical Report 17, National Park Service, Cooperative Parks Studies Unit, University of Arizona.

USDI National Park Service. 1988. Backcountry Management Plan. Grand Canyon National Park, AZ.

———. 1995. General Management Plan. Grand Canyon National Park, AZ.

———. 2006. Management Policies 2006. Washington, DC.

United States Department of the Interior. 2011. A Call to Action: Preparing for a Second Century of Stewardship and Engagement. Policies. Washington, DC: National Park Service.