See end of article for credits and captions.

Beyond Secretaries, Hostesses, and Cooks: The Power, Humility, and Compassion of Women Who Battled to Save Wilderness

Communication & Education

April 2021 | Volume 27, Number 1

In 1964, the 88th Congress passed an act to establish the National Wilderness Preservation System for the permanent good of the whole people, and for other purposes. This act is commonly referred to as The Wilderness Act. Many stories are told about the men leading the charge for wilderness preservation. These stories usually include three figures: Aldo Leopold, the well-known wildlife biologist, author, and ecologist; Robert Marshall, the philanthropist, forester, and cofounder and financier of The Wilderness Society; and Howard Zahniser, longtime president of The Wilderness Society and primary author of the Wilderness Act. Maybe some people even know about the more obscure Arthur Carhart who drafted the first known government memo explaining the idea of preserving natural lands for purposes other than development (the first mention of wilderness 23 years before the Wilderness Act was passed), or Sigurd Olson, author and National Parks Association president who helped write many drafts of the Wilderness Act. But there are other figures whose stories are seldom told in wilderness history.

Before the Wilderness Act was passed, 66 drafts of the bill were written, and Congress debated for eight years. During this time, from the 1940 to the 1960s, women were still seen as homemakers and husbands’ helpers. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy established the Commission on the Status of Women and appointed Eleanor Roosevelt as chairwoman. In a televised 1962 discussion with Roosevelt, Kennedy stated, “We want to be sure that women are used as effectively as they can to provide a better life for our people, in addition to meeting their primary responsibility, which is in the home” (McLaughlin 2014).

Society viewed women as homemakers and housewives. It is no surprise then, that stories of women’s role in our wilderness history are seldom told. It would be distressing if future historical accounts left out Greta Thunberg or Ruth Bader Ginsberg when recounting environmental activism or gender discrimination. And it is similarly disheartening that the important female figures of our wilderness history are not credited. These stories have a critical place and need to be heard.

It would be distressing if future historical accounts left out Greta Thunberg or Ruth Bader Ginsberg when recounting environmental activism or gender discrimination. And it is similarly disheartening that the important female figures of our wilderness history are not credited. These stories have a critical place and need to be heard.

Margaret “Mardy” Murie (1902–2003)

Figure 1 – Mardy and Olaus Murie in fur parkas. Taken in January 1925 after they returned from their honeymoon. Credit: USFWS.

Probably the most well-known woman in wilderness history is Margaret “Mardy” Murie, considered the matriarch of the wilderness movement. Mardy was a field biologist, a teacher, and an author. In her book, Two in the Far North, she advocated for wilderness protection in Alaska. Mardy was the first woman to graduate from the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines, now University of Alaska (Wilderness.net 2020). With her husband, Olaus Murie, she continued to explore Alaska while Olaus served as a wildlife biologist for the Bureau of Biological Survey, now the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Together they served in various roles for both the Izaak Walton League and The Wilderness Society.

In 1956, Mardy, Olaus, and other field biologists traveled to the upper Sheenjek River on the south slope of the Brooks Range, inside what is now the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Their mission was to garner support and gain protection for an entire ecological system as the Arctic National Wildlife Range. The couple recruited former US Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas to help persuade President Dwight D. Eisenhower to consider their campaign. President Eisenhower established the range in 1960 and set aside more than 8 million acres (3,237,485 ha) for the “unique wildlife, wilderness, and recreational values” (Donahey 2018). After Olaus’s death in 1963, Mardy continued to fight for wilderness preservation, writing letters, articles, and speaking at hearings. She returned to Alaska to survey potential wilderness areas for the National Park Service and campaign for the Alaska National Interest Conservation Lands Act. Her devotion to wilderness is apparent in her testimony to Congress in 1977 for the Alaska Lands Act,

I am testifying as an emotional woman and I would like to ask you, gentlemen, what’s wrong with emotion? Beauty is a resource in and of itself. Alaska must be allowed to be Alaska, that is her greatest economy. I hope the United States of America is not so rich that she can afford to let these wildernesses pass by, or so poor she cannot afford to keep them. (Mongillo and Booth 2001)

The Alaska National Interest Conservation Lands Act passed in 1980. In addition to renaming the Arctic Wildlife Range the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Congress gave protection to 104 million acres (42,087,307 ha) as various conservation lands and included increasing the size of the range/refuge by 10 million acres (4,046,856 ha). Mardy’s contribution to conservation and preservation in Alaska helped protect some of the last remaining wilderness in the country.

In October of 2003, Mardy died in her cabin in Moose, Wyoming, at the age of 101. Upon her death, a Los Angeles Times staff writer wrote, “Mardy Murie served as her husband’s secretary, hostess, and cook as well as forthright adjunct in his preservation activities” (2003).

In 1998, Mardy was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton for her lifetime service to conservation (Teton Science Schools 2020). Those who knew her speak of how she touched their lives and inspired them. I hope that Mardy can be remembered as an inspirational leader and for dedication to wilderness and conservation; not only as her husband’s secretary, hostess, and cook.

Virginia (Ginny) Hill Wood (1917–2013) and Celia Hunter (1919–2001)

Celia Hunter and Virginia Hill Wood were two women whose lifelong friendship, love of adventure, and pioneer spirits created a conservation legacy in Alaska. Celia and Ginny met in the early 1940s when they both served in World War II as Women Air Force Service Pilots (WASPs) and ferried military planes throughout the lower 48 (Kaye 2019). During this time, WASPs were not permitted to fly planes to Alaska, which only piqued their curiosity and interest. In 1947, after the WASPs were dismantled, they met a pilot in Seattle who hired them to deliver surplus Stinton airplanes to Alaska. In December, they set out on a frigid 27-day flight to Fairbanks and arrived cold but not dismayed. Perhaps it was inevitable that the adventurous pair would stay in Alaska (Kaye 2019). They continued to fly, either on commercial planes as flight attendants or as pilots for the fledgling tourism industry. The adventurous pair quickly decided large-scale tourism wasn’t their style and with Ginny’s husband, began to look for a wilderness setting where they could offer a simpler tourist experience (Kaye 2019).

In 1952, they filed a Homestead Act claim for property near Denali National Park with a view of the majestic peak. The trio opened the first ecotourism operation in Alaska and called it Camp Denali. This experience offered guests the opportunity “to live for a while in the midst of primeval grandeur” (Denali Dispatch 2016). Living and working at Camp Denali deepened their respect and admiration of Alaska’s wild lands. In the late 1950s, Celia met Olaus and Mardy Murie and was inspired by their fight to set aside vast wilderness areas in the Alaska territory (Kaye 2019). In 1960, Alaska senator Bob Bartlett scheduled hearings throughout Alaska to build and strengthen opposition to the proposal for an Arctic wildlife refuge. Ginny and Celia set out to recruit Alaskans in support of the refuge to testify at these hearings. Ginny’s testimony reflects her passion for wilderness values (Kaye 2019).

The wilderness that we have conquered and squandered in our conquest of new lands has produced the traditions of the pioneer that we want to think still prevail: freedom, opportunity, adventure, and resourceful, rugged individuals. These qualities can still be nurtured in generations of the future if we are farsighted and wise enough to set aside this wild country immediately, and spare it from the exploitations of a few for the lasting benefit of the many (Alaska Women’s Hall of Fame 2020).

Ginny and Celia were successful; most of the testimonies were in support of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (Kaye 2019).

During this fight, they realized the need for an organized environmental group and created the Alaska Conservation Society (ACS), the first of its kind in the state. ACS continued to fight for conservation in Alaska and played a primary role in ending two large-scale energy projects (Alaska Women’s Hall of Fame 2020). In the early 1970s, Celia became increasingly active in grassroots efforts to pass what would later become the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. Both women were strong supporters and were heavily relied on for their extensive knowledge of issues in Alaska (Kaye 2019). In 1976, Celia became the first woman executive director of The Wilderness Society – the first for any national environmental organization. Her role as a female executive director was not uncontroversial though, and she was met with disapproval. Despite this, her time in leadership was later described by a coworker as “an unforgettable lesson in the power of grace, humility, and humor in response to bias and criticism” (Kaye 2019). In 1980, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act passed, protecting more than 100 million acres (40,468,564 ha) as national parks, refuges, forests, and wilderness.

Figure 4 – Celia Hunter and Ginny Hill on the porch of Romany’s cabin at Camp Denali. Early 1960s. Credit: Northern Alaska Environmental Center.

Celia and Ginny inspired people through their activism, writings, and daily life. Celia frequently wrote columns for the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner and Ginny wrote for the Northern Alaska Environmental Center, of which she was a founding member. Celia and Ginny received numerous accolades for their conservation work. In 1991 they were awarded the Sierra Club’s John Muir Award and in 2001 Alaska Conservation Foundation’s Lifetime Achievement Award (Alaska Women’s Hall of Fame 2020). Former governor Jay Hammond called Celia and Ginny “the grand dames of the environmental movement.” Celia and Ginny never lost their enthusiasm for wilderness and conservation. May their stories continue to inspire us into action.

Pauline “Polly” Dyer (1920–2006)

Polly’s story is an unfortunate example of how inaccurate historical narratives undermine the contributions of women throughout history.

Polly’s love for the outdoors began in the 1940s when her family moved from the East Coast to Ketchikan, in the Alaska Territory. She later testified in front of Congress in support of wilderness that her years in Alaska “were the basis for my whole life since” (Becker 2010). From 1947 to 1950, she and her husband spent time rock climbing, sailing, and backpacking thorough the Sierra Nevada range. It was during this time that she claimed she became an environmentalist.

In 1950, Polly moved with her husband from Berkeley, California, to Auburn, Washington, where they enthusiastically explored the Cascade and Olympic ranges. They joined the Mountaineers, and Polly initiated and served on the Mountaineers’ Conservation Committee (Sowards 2020). In 1953, Polly, her husband, and two friends founded the Pacific Northwest Chapter of the Sierra Club, the first chapter outside of California. This same year she was appointed by the governor to serve on a committee to investigate a possible transferal of portions of Olympic National Park to the US Forest Service for commercial logging operations. In this role, she led the Mountaineers in a letter-writing campaign, submitting more than 300 letters. In the end, Dyer’s leadership and the Mountaineers’ advocacy proved instrumental in helping defeat the plan (Becker 2010).

The world of environmental activists was a much smaller one back then. In the mid-1950s, Polly Dyer met Howard Zahniser, executive secretary of The Wilderness Society, when they both fought to stop the construction of the Echo Park Dam in Dinosaur National Monument. Years later, during a visit to Polly’s home in Seattle, Howard heard her use the word “untrammeled” in a campaign to protect stretches of coastline near Olympic National Park (Young 2019). Stories differ as to whether she recommended the word in his drafts of the wilderness bill. Regardless, it was her enthusiastic use of the word that inspired and swayed Howard to adopt this word as the primary descriptor of wilderness.

Unfortunately, his inspiration is seldom attributed to Polly. In The Wilderness Society’s tribute to Howard Zahniser as the “unsung architect” of the Wilderness Act they write, “At some point in the process, Zahniser, allegedly inspired by the seashore near Olympic National Park, added a word he felt perfectly evoked the rugged, unique quality of wilderness-type lands to be spared mankind’s undue abuse, which would become the bill’s quintessential flourish: ‘untrammeled’” (Greenberg 2016).

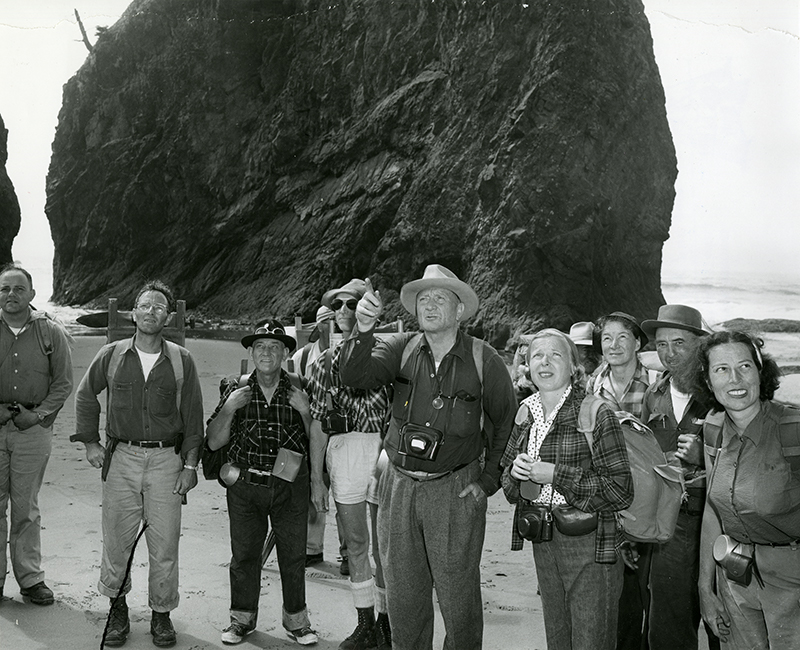

Polly continued to fight for federal legislation to protect wilderness. As the founder of the Mountaineers Conservation Committee, Polly pushed for recognition of Glacier Peak in the North Cascades, a campaign the Mountaineers engaged in starting in the late 1920s. In 1957, at a Senate committee hearing regarding copper exploration in the North Cascades, Polly stated, “Wilderness cannot and should not wear a dollar sign. It is a priceless asset which all the dollars man can accumulate will not buy back” (Becker 2010). In 1958, Polly organized a hike to protest a proposed road on the Ocean Strip of Olympic National Park. The hike drew many notable figures of the time including Justice William O. Douglas, Howard Zahniser, Wilderness Society cofounder Harvey Broome, author and National Parks Association president Sigurd Olson, and Mardy Murie, among others (Sowards 2020). The hike lasted three days and covered more than 20 miles (32.2 km) and was a key moment in the environmental movement in the Northwest.

Figure 5 – Polly Dyer, far right, and William O. Douglas, center, on a hike protesting proposed coastal highway in Olympic National Park (August 19, 1958). Credit: University of Washington; Bob and Ira Spring Collection

In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the bill that created North Cascades National Park. Polly was one of fiercest and most active proponents for the park but upon its creation, shied away from taking credit (Sowards 2020). I wonder if this shyness also explains her unrecognized contribution to the Wilderness Act.

The list of accomplishments and awards attributed to her is extensive. When asked what distinguished her from other environmentalists, Peter Jackson of the North Cascades Institute answered, “Humility. She had grace and presence. She was perfectly happy to let others take credit” (Young 2019).

Maybe it’s no coincidence, then, that the word she contributed to the Wilderness Act, the single most important word in the act, is also one that wilderness professional associate with humility and restraint. “Untrammeled.”

Helen Fenske (1923–2007)

Helen Fenske’s wilderness contribution may seem small, protection of fewer than 4,000 acres (1,618.7 ha), but it was historical nonetheless. Helen fought for protection of marshes and meadows a mere 26 miles (41.8 km) from Times Square, an area that was eyed for multiple development projects. Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge Wilderness was the first wilderness designated by the Department of the Interior, and Helen Fenske played a prominent role in galvanizing citizen support.

Helen, a “housewife who lived on the edge of the swamp,” became an early leader for the Great Swamp campaign (Barry 2000). In 1959, the Port Authority of New Jersey and New York announced a plan to fill in the Great Swamp to develop a new multimillion dollar airport slated to be “the world’s largest international jetport” (Fenyk 2014). Years before the jetport project was announced, the area was eyed for an apartment complex and then a pipeline project. Due to this history and the swamp’s proximity to three universities, a substantial body of research and knowledge about the unique ecosystem of the Great Swamp Basin already existed. The area was home to 39 species of mammals and a nesting site for 244 species of birds. The Great Swamp Committee used this data to formulate a proposal that the area be designated a National Wildlife Refuge (Fenyk 2014). The proposal was sent to US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) headquarters in Washington, D.C., but fell on deaf ears. After a meeting with FWS regional officials in Boston, Helen and Grace Hand, a friend and fellow supporter, went to the universities and gathered all the biological and ecological information they could find on the area.

On a second visit to the regional office, armed with their research, Helen secured a promise from the regional director; if the Great Swamp Committee could purchase 3,000 acres (1,214 ha), he would open a USFWS Office there and assign a manager (Nally 2013).

Figure 6 – The work of Helen Fenske (1923-2007) is acknowledged at the 1960 dedication of the Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. Credit: USFWS

This ignited hope, and the Great Swamp Committee, led by Helen, sprang into action. But purchasing thousands of acres was not easy. The area had hundreds of woodlots dating back to the 1700s for which they needed the guaranteed titles before the FWS would proceed (Madison and Koch 2013). With the help of some local elites, the relentless committee raised $5,000,000 to purchase the titles to 2,600 (1,052 ha) acres of land. On May 29, 1964, the secretary of the interior oversaw the dedication of the refuge. But the Port Authority had not lost interest. They continued to propose highways, sewer plants, and other projects for the refuge and adjacent lands (Madison and Koch 2013).

The Wilderness Act was signed into law on September 4, 1964. Helen sat in her office reading a news article about the newly passed law (Madison and Koch 2013). Section 2(c) of the act provides a definition of wilderness. In this section it states, “An area of wilderness is further defined to mean in the Act an area … which … has at least five thousand acres of land or is of sufficient size as to make it practicable its preservation and use in an unimpaired condition.” She was struck by the words in the article she held in her hands, “Islands of Wilderness.” This, she thought, was the answer! She immediately contacted The Wilderness Society and began to learn all she could about wilderness protection and the process for proposing wilderness. Although the total acreage did not meet the 5,000-acre (2,023 ha) criteria, she knew that wilderness designation was the only way to finally shut down the continuing assault of development interests (Madison and Koch 2013). The Wilderness Society continued to guide the Great Swamp Committee until the hearing for wilderness legislation was scheduled. At the final hearing, there were only two dissenting voices from labor unions in favor of the jetport. Fellow activist David Moore of the New Jersey Conservation Foundation said, “No one had taken on the Port Authority, and certainly no one had taken them on and won” (USWFS 2015). But Helen did.

Figure 7 – Helen Fenske reflects on the swamp that could have become tarmac but instead became a refuge 25 miles (40.2 km) west of Times Square. Credit: Fenske family

The Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge Wilderness was one of the last pieces of legislation that President Lyndon B. Johnson signed before leaving office. Shortly after, Lady Bird Johnson held a luncheon at the White House to celebrate the Highway Beautification Act and invited Helen Fenske to speak about the successful campaign for the Great Swamp (Madison and Koch 2013). During this speech she said, “Our story is not remarkable, nor unusual at all” (Kitchell and Rosenberg 2020).

Helen noted in an interview in 2000, “There were a lot of people who contributed to the campaign.” Abagail Fair, of the Association of New Jersey Environmental Commission, said about Helen, “People have got to tip their hats to her for saving this area. Without her energy and her intelligence, I think we would be the fourth metropolitan jetport” (NJ Hills Media Group 2007).

I’d say that the fight continued and succeeded because of Helen’s determination and spirit. As wilderness managers, her humble disposition is something we can all aspire to achieve in our own wilderness management.

Figure 8 – Caribou graze on the Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, with the Brooks Range as a snowy backdrop. Credit: USFWS.

Sarah James (1946–present)

On the Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge there is a place referred to as The Sacred Place Where All Life Begins (Izhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit) by the Gwich’in of Alaska. The Gwich’in live south of the Brooks Range where their villages are strategically located along the Porcupine Caribou Herd’s migration paths. The coastal plains serve as birthing and nursery grounds for the herd and are deeply intertwined with Gwich’in way of life (Ashley 2019).

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter expanded the Arctic National Wildlife refuge from 8.9 million acres (3,601,702 ha) to almost 19 million acres (7,689,027 ha) and designated most of these acres as wilderness. The 1.5-million-acre (607,028-ha) Coastal Plain was left unprotected. Soon after the wilderness designation, legislative attempts were made to open the Coastal Plain in the refuge to oil exploration and drilling (Donahey 2018).

Legislation to protect the Arctic Refuge Coastal Plain as wilderness has been introduced in every Congress beginning in 1986 (Donahey 2018). The Coastal Plain is described as “the most biologically productive part of the Arctic Refuge for wildlife and is the center of wildlife activity” (Llanos 2004). Sarah James is a native Neetsa’ii Gwich’in and has championed protection of the Coastal Plain for decades. In 1988, the Gwich’in leaders from across Alaska and Canada developed a resolution to formalize their opposition to energy development in the refuge and their support for wilderness designation of the Coastal Plain. Sarah was asked to serve as one of the eight representatives that would take this to the political arena. Sarah now serves as chairperson for the Gwich’in Steering Committee and as the official spokesperson on Arctic Refuge issues for the three Neetsa’ii Gwich’in tribal governments at the refuge’s borders (Madison and Chase 2016).

Sarah has traveled internationally to give speeches and testimonies about the importance of the Porcupine Caribou Herd. In 2000, she met with former President Jimmy Carter, who pledged to her that he would ask then President Bill Clinton to declare the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge a national monument. In 2002, Sarah was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize for her grassroots environmental activism with the Gwich’in (Goldman Prize 2002). In 2005, Sarah kept a five-month vigil near the Capitol to protest George W. Bush’s second attempt to allow oil exploration in the refuge (Harball 2019).

In 2006 Sarah stated, “The calving and nursery grounds will never be completely safe until the Arctic Refuge has wilderness designation. We have to continue to educate people and work like we have since 1988 in order to protect the Sacred Place Where Life Begins” (Grist staff 2006). In 2015, The Wilderness Society awarded Sarah their Robert Marshall Award, their highest honor, for her conservation and land ethic work. The Ford Foundation awarded Sarah a fellowship as one of the Emerging Leaders in a Changing World. She was one of 20 chosen from 3,000 applicants (Gildart 2020 n.d.).

After 50 years of advocacy, Sarah continues to speak for the caribou and the refuge using positive messaging and compassion. Gail Small, a friend and executive director of Native Action, says that “Sarah never tries to be someone who’s angry, or aggressive. She just talks her story.” This strategy has served Sarah and her cause well (Harball 2019). She continues to win battles against oil interests and repeated attempts in Congress to legalize drilling in the Coastal Plain of the refuge.

Figure 9 – Sarah James speaking at the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge 50th Anniversary. Credit: 2011 Arctic NWR Symposium at NCTC. Photographer: Cara Schildtknecht/USFWS.

In 2017, the Arctic Refuge lost crucial protection and was opened to the energy industry for oil and gas leasing. Area 1002, the target location, is thought to overlie a geological formation that could be holding millions of barrels of oil. Area 1002 is also part of the Porcupine Caribou Herd’s migration route and calving grounds (Eaton 2020).

Sarah is leading the campaign against exploration in The Sacred Place Where Life Begins, and thanks to her, the issue has gained nationwide attention. She continues to campaign for wilderness designation.

Her lifetime commitment to conservation of the Coastal Plain is inspiring but, like others when asked about it, she modestly replies, it’s just my way of life. “We’ve always been there …the creator put us there to take care of that part of the world” (Eaton 2020).

The world is lucky that she is there.

Closing Remarks

These are but a few stories that emphasize the contributions of women environmentalists and conservationists to our wilderness history. There are others, though; Doris Milner was instrumental in the preservation of the Magruder Corridor in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness in Montana; Diane Newell Meyer chaired a regional wilderness conference in 1972 to spur support for wilderness designation of six areas in Oregon; Heather Morijah contributed to the fight for designation of the largest roadless area remaining in the Great Plains; Marge Sill’s work led to the passage of the Nevada Wilderness Protection Act and designation of 13 new wilderness areas across the state; Marjory Stoneman Douglas is well known for her campaign to protect the Everglades as a national park and later a wilderness; Jaylyn Gough is the founder and executive director of Native Women’s Wilderness; and Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk continues to fight for protection of Bears Ears in Utah.

These women are talented and passionate pioneers. Their stories should be told so they continue to inspire other women who fight for wilderness. We should all show reverence to the power of the grace, humility, and compassion showed by the women who battled and continue to battle to protect wilderness.

About the Authors

MICHELLE L. REILLY, PhD, is an ecologist and the wilderness liaison for the Fish and Wildlife Service Refuge System at the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center in Missoula, Montana; email: Michelle_Reilly@fws.gov.

References

Alaska Women’s Hall of Fame. 2020. Ginny Hill Wood. http://alaskawomenshalloffame.org/alumnae/name/virginia-ginny-wood/, accessed October 20, 2020.

Ashley, R. 2019. In Northern Alaska, a human rights imperative. https://www.alaskawild.org/blog/in-the-arctic-a-human-rights-imperative/, accessed October 27, 2020.

Barry, J. 2000. A Citizen’s Guide to Grassroots Campaigns. New Brunswick, NJ: University Press.

Becker, P. 2010. Dyer, Pauline (Polly) (1920–2016). HistoryLink.org, Essay 9673. https://www.historylink.org/File/9673, accessed October 8, 2020.

Denali Dispatch. 2016. The legacy of Ginny Wood and Celia Hunter. https://campdenali.com/blog/ginny-wood-celia-hunter, accessed October 25, 2020.

Donahey, L. 2018. A brief history of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. https://www.alaskawild.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Arctic-Refuge-brief-history-2018.pdf.

Eaton, D. 2020. Sarah James: Fighting for what’s sacred in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. https://crcc.usc.edu/sarah-james-fighting-for-whats-sacred-in-the-arctic-national-wildlife-refuge/, accessed November 2, 2020.

Fenyk, H. M. 2014. Citizen expertise and advocacy in creation of New Jersey’s 1987 freshwater Wetlands Protection Act. PhD dissertation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, pp. 101–108.

Greenberg, M. 2016. The Wilderness Society, tribute to Howard Zahniser, unsung architect of the Wilderness Act. https://www.wilderness.org/articles/blog/tribute-howard-zahniser-unsung-architect-wilderness-act, accessed October 3, 2020.

Gildart, B. 2020. First-Nations.org.https://www.first-nations.info/sarah-james-leads-alaskas-caribou-people-defense-life.html, accessed October 15, 2020.

Goldman Prize. 2002. https://www.goldmanprize.org/recipient/sarah-james-norma-kassi-jonathon-solomon/, accessed October 25, 2020.

Grist. 2006. Sarah James Gwich’in activist and environmental prizewinner, answers questions. https://grist.org/article/james1/, accessed November 1, 2020.

Harball, Elizabeth. 2019. “We’re never going to surrender” – Sarah James on a life fighting oil drilling in the Arctic Refuge. https://www.alaskapublic.org/2019/07/17/sarah-james-on-a-life-fighting-oil-drilling-in-the-arctic-refuge/.

Kaye, R. 2019. The Legacy and Lessons of Celia Hunter.

Kitchell, M., and J. Rosenberg. 2020. “Unremarkable,” Helen Fenske’s unlikely legacy. USFWS Conservation History Journal 4(1): 45–47.

Llanos, M. 2004. Bets are on for drilling in Arctic refuge. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna6407196, accessed November 5, 2020.

Los Angeles Times. 2003. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2003-oct-22-me-murie22-story.html,accessed October 5, 2020.

Madison, M., and S. Chase. 2016. Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The first 50: A historical symposium on Arctic Wildlife Refuge 1960–2010. https://www.fws.gov/uploadedFiles/Region_7/NWRS/Zone_1/Arctic/PDF/ArcticNWR50thSymposiumTransactions.pdf accessed November 5, 2020.

Madison, M., and B. Koch. 2013. Helen Fenske oral history transcript. National Conservation Training Center Archives Museum.

McLaughlin, Katie, 2014. 5 things women couldn’t do in the 1960s. https://www.cnn.com/2014/08/07/living/sixties-women-5-things/index.html, accessed October 1, 2020.

Mongillo, J. F., and B. Booth. 2001. Environmental Activists. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Nally, L. 2013. Conserving Great Swamp: How Helen Fenske helped establish a refuge. https://usfwsnortheast.wordpress.com/2013/03/15/conserving-great-swamp-how-helen-fenske-helped-establish-a-refuge/.

NJ Hills Media Group. 2007. Helen Fenske, lioness of NJ’s environmental movement dies at 84. https://www.newjerseyhills.com/helen-fenske-lioness-of-new-jerseys-environmental-movement-dies-at-84/article_71cdd832-4efa-5096-8f8b-cc55bde55734.html.

Sowards, A. 2020. An Open Pit Visible from the Moon: The Wilderness Act and the Fight to Protect Miners Ridge and Public Interests. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Teton Science Schools. 2020. The Murie Legacy. https://www.tetonscience.org/locations/murie-ranch/the-murie-legacy/, accessed October 5, 2020.

US Fish and Wildlife Service. 2015. USFWS Refuge Update. A look back … Helen Fenske. https://issuu.com/nationalwildliferefugesystem/docs/mar-apr_2015_refugeupdate508, accessed October 24, 2020.

Wilderness.net. 2020. Olaus and Mardy Murie. https://wilderness.net/learn-about-wilderness/olaus-mardy-murie.php, accessed October 5, 2020.

Young, B. 2019. Office of the Secretary of State, Legacy Washington. A sweeping legacy – Polly Dyer. https://www.sos.wa.gov/legacy/sixty-eight/polly-dyer/, accessed October 14, 2020.

Photo Credits

Read Next

Protected Areas in a Post-Pandemic World

I am excited that 2021 brings us the 27th volume of the International Journal of Wilderness, and with is comes new beginnings.

Interpreting John Muir’s Legacy

In judging Muir’s legacy, we should be compelled to look inward, admit our own shortcomings, and acknowledge that we, too, have been participants in a system that oppresses Black Americans, Indigenous peoples, and other people of color.

The Curse of the Wild Horses: Deromanticizing Feral Horses to Save Australia’s Kosciuszko National Park

This article documents two walks in the Byadbo Wilderness Area of Australia’s Kosciuszko National Park that revealed inordinate numbers of feral horses, whose population has increased rapidly despite ongoing drought and consequent environmental damage