Fishing in Montana’s Great Bear Wilderness. Photo credit: Antonio Ibarra/Montana statewide photographer for Lee Newspapers.

Can We Make Wilderness More Welcoming?

An Assessment of Barriers to Inclusion

by LISA RONALD and SALAH AHMED, KATIE BLISS, JESSE CHAKRIN, TANGY EKASI-OTU, KIMM FOX-MIDDLETON, JENN HARRINGTON, SHELTON JOHNSON, TINA MAZZEI, JESSI MEJIA, and ROGER OSORIO

Stewardship

June 2023 | Volume 29, Number 1

PEER REVIEWED

ABSTRACT

Perspectives about and values for wilderness vary greatly among people who are underrepresented in wilderness recreation and management. Understanding divergent interpretations of wilderness can better equip communicators to evaluate how well communications strategies resonate with audiences, including potential and current wilderness visitors, employees, and partners. A committee of individuals from systemically excluded groups conducted a reflective assessment of wilderness attributes and norms and how they are communicated, revealing potential inclusivity barriers to wilderness under four themes: Wilderness History and Culture, Fundamental Wilderness Qualities, Gender Assumptions, and Access to Wilderness. This reflective assessment can also help communicators broaden and reenvision traditional narratives about wilderness history, culture, and values to respectfully include diverse stories, varied experiences, and relationships between wilderness, other social forces, and historical events.

Natural resources communicators, including those who work in interpretation, advocacy, or for the media, hold incredible power in shaping perceptions of public lands and wilderness. Communicators control or influence whose voices are elevated or excluded, which perspectives history is recounted from, and how information is distributed and to whom. In this article, we present an assessment designed to understand diverse perspectives about wilderness and tools to develop more inclusive communications strategies and practices. We begin with the social context in which this topic is positioned.

George Floyd’s murder by police in May 2020 prompted a nationwide racial reckoning. In the years following these events, many conservation nonprofits, government land management agencies, research institutions, and higher education institutions have responded with commitments to diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice. The Sierra Club’s president Michael Brune published a blog post that immediately brought the organization – arguably the first large, national wilderness organization to publicly address racism in conservation – into the environmental justice spotlight. Brune’s post linked the Sierra Club’s long-time idolization of John Muir and the conservation culture he helped create to the perpetuation of institutional racism. Brune (2020) wrote, “The whiteness and privilege of our early membership fed into a very dangerous idea – one that’s still circulating today…. It allows [Sierra Club members] to overlook, too, the fact that only people insulated from systemic racism and brutality can afford to focus solely on preserving wilderness.”

About six months later, in January 2021, President Joe Biden officially recognized diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice as part of his inaugural priorities and pillars of today’s government. Through Executive Order 13985 (2021) his administration established that “affirmatively advancing equity, civil rights, racial justice, and equal opportunity is the responsibility of the whole of our government.” The following month, the University of Montana, like many other higher-education institutions before it, took actions to address equity by creating the Office of Inclusive Excellence for Student Success. In its Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Plan, last updated in September 2021, the University of Montana commits to “an aggressively introspective approach to identifying the equity gaps unique to our institution, flagging the policies and practices that contribute to these gaps, and implementing new policies and practices that will bridge them.” Although the US Civil Rights Act was signed into law more than 50 years ago, the same year as the Wilderness Act, the quick succession of the previously mentioned events provides social context wherein the University of Montana’s Wilderness Institute proposed an audit of its interpretive wilderness content.

The purpose of this article is to identify communications barriers, explain why certain language and concepts specific to wilderness may privilege some individuals or groups while excluding others, and suggest strategies for producing more inclusive communications materials. To address this purpose, we describe how and why a Wilderness Inclusivity Review Committee of individuals with systemically excluded identity characteristics was formed to conduct an audit of wilderness communications that we refer to as a reflective assessment. Through this assessment, we present diverse interpretations of key aspects of wilderness and how they are communicated.

Figure 1 – Hiking in the Oregon’s Mt. Hood Wilderness. Credit: Kimm Fox-Middleton.

Among the top 25 most popular TED talks, Nigerian feminist author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (TED 2009, 0:13) warns of “the danger of the single story.” She describes how a repeated, definitive interpretation, legitimized through literature and media by those with power, can marginalize different representations of the same thing. When one story becomes the only story, this can create an incomplete picture – in this case, of wilderness. Moon and Pérez-Hämmerle’s (2022) work similarly suggests that language driven by dominant worldviews can marginalize people through real social and ecological consequences. Our diverse interpretations of wilderness are thus presented to broaden and enrich the current single story of wilderness – its history, culture, values, and meanings.

Understanding and relaying a multifaceted, inclusive wilderness story is critical for land management agency and nonprofit employees looking to forge respectful connections with wilderness visitors, employees, partner groups, volunteers, and students, especially those who may have experienced discrimination in the outdoors in general, or within wilderness specifically. We intend for this reflective assessment to assist communications, public affairs, visitor services, interpretation, outreach, education, and land management professionals with inclusive language concepts specific to wilderness.

In this article, we first begin by sharing how terms and definitions were used by the review committee and within the reflective assessment. Next, we examine previous literature to better understand the underlying historical and social context of the wilderness story. We discuss process, creation, and purpose of the review committee and the implementation of the reflective assessment. Then, we present the potential inclusivity barriers to wilderness revealed by the reflective assessment under the four themes of Wilderness History and Culture, Fundamental Wilderness Qualities, Gender Assumptions, and Access to Wilderness. Finally, using examples we discuss how awareness and understanding of these potential barriers can help communicators broaden and reenvision traditional narratives about wilderness history, culture, and values to respectfully include diverse stories and varied experiences.

Terms and Definitions

We have chosen specific terms to refer to different types of people. Throughout this article, we use the term “systemically excluded groups” to refer to all types of people who have been, and continue to be, discriminated against by racist or colonialist policies. Although other adjectives such as “marginalized” and “historically excluded” are used widely, language that victimizes those who are oppressed or confines oppression to the past can fuel continued discrimination (First Nations Development Institute 2018; Younging 2018). “Systemically excluded” better recognizes exclusion as ongoing and systemic within everything from hiring systems to social norms (Race Forward: The Center for Racial Justice Innovation 2015; Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture 2022).

There are many different types of systemically excluded groups. For example, some Americans of African descent may consider themselves to be African Americans, while others may prefer to be referred to as Black (Harmon 2021). Although there are various popular terms, we chose specific terms including BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color [those who do not identify as White]), African American, Indigenous, LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual/agender, plus others), women, Latinx, AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander), and people with disabilities, for example, when it is necessary to refer to people in groups where context necessitates distinction (Kanigel 2019; Race Forward: The Center for Racial Justice Innovation 2015). Since people have mixes of identity characteristics – such as race, gender, economic status, ability, and so forth – certain individuals may self-identify as members of more than one systemically excluded group. For example, someone who identifies as an African American transgender person may consider themselves to be part of systemically excluded groups based on both race and gender, separately and/or together. We acknowledge that these terms may change over time as systemically excluded groups assert greater control over the language used to describe themselves (Harmon 2021). Those working directly with systemically excluded groups should strive to understand how these groups identify themselves and the language with which they do so.

Figure 2 – Hiking in Montana’s Great Bear Wilderness. Credit: Antonio Ibarra/Montana statewide photographer for Lee Newspapers.

Although the term “intersectionality” was coined decades ago (Crenshaw 1989), its application to environmentalism is more recent (Thomas 2022). Intersectionality identifies and acknowledges how bias and prejudice against individuals with different but overlapping identity characteristics can create compounding systems of discrimination or disadvantage (TED 2016). For example, African American women face both racial and gender discrimination that is unique and different from discrimination faced by White women or African American men. Intersectional environmentalism identifies and acknowledges how social inequities influence environmental perceptions and connections (Intersectional Environmentalist Council 2022; Oglesby 2021; Thomas 2022). Application more specifically to wilderness means that society cannot ignore the ways in which poverty and climate justice, for example, influence people’s access to and understanding of wilderness. Throughout this reflective assessment, we identify ways in which social forces and spheres of discrimination compound, overlay, and/or intersect in ways that present barriers to inclusive communications about wilderness.

Background

We feel it is important to provide the underlying historical and social context that is missing from the traditional wilderness narrative but is necessary to facilitate understanding of wilderness critiques through an equity lens. African American author and wildlife ecologist Dr. Drew Lanham described the process of acknowledging historical and systemic racism in wilderness akin to cleaning out a wound, a process that is painful and requires baring of the affected flesh to preclude infection during healing (Bob Marshall Wilderness Foundation 2021) – a process that the Sierra Club began with its rebuke of John Muir (Brune 2020).

Several authors have provided assessments of wilderness and conservation history from noncolonial perspectives. Indigenous author Gilio-Whitaker (2019) described the formation of public lands and wilderness through Indigenous land dispossession, and Ybarra (2022) recounted a second wave of land dispossession that took place in the Desert Southwest and has affected generations of Mexican American settlers. Theriault and Mowatt (2018) focused on the complex and nuanced role of wilderness as both a place of oppression and refuge for enslaved African Americans pre- and post-Civil War and during Jim Crow, and Taylor (2002, 2016) chronicled a broad-reaching and detailed history of land policy discrimination against Indigenous peoples, African Americans, members of the Latinx community, AAPI, and other systemically excluded groups. And Reilly’s (2021) work revealed the important, yet hidden, contributions to the wilderness movement from female advocates. Together, these examinations demonstrate the lack of systemically excluded groups and their stories within the traditional wilderness narrative – one that recounts history from the perspectives of well-known White male environmentalists such as John Muir, Arthur Carhart, Bob Marshall, Howard Zahniser, Aldo Leopold, and others.

Critiques of wilderness also include those from authors who discuss discrimination within wilderness and public land philosophy, recreation, and management from relational, racial, and sexual perspectives. Specifically, Indigenous authors Bayet (1994), Gilio-Whitaker (2019, 2020), LaPier (2021), and Standing Bear (1933) have challenged a core tenet of wilderness and public lands – that of nature absent and separate from people – as a fundamental and profound disconnect between Indigenous and White land relationships that is dehumanizing to Indigenous peoples and represents a present-day extension of colonial oppression. Fletcher et al. (2021) further suggested that the absence of reciprocal relationships between people and land, inherent in a wilderness definition absent of people, has resulted in ecosystem degradation in some landscapes. In the context of recreation, land dispossession, enslavement, and other forms of intergenerational trauma have served as barriers and constraints to participation in outdoor recreation by systemically excluded groups (Dietsch et al. 2021; Johnson 1998). Intimidation, fear of physical harm, and wariness around being the only person of color in a remote, White-dominated outdoor space have also been drivers of decisions by BIPOC around where and whether to participate in outdoor recreation (Graham 2020). And with a lack of recognition of the different ways in which systemically excluded groups connect with nature (Graham 2018; Theriault and Mowatt 2018), management-imposed restrictions on traditional recreation and subsistence activities have influenced outdoor recreation participation and relationships with wilderness (Davis 2019).

In relationship to sexual perspectives, Mortimer-Sandilands and colleagues (2010) have asserted that predominant heterosexual nature relationships have subverted queer ecologies. The advancement of queer ecology, ecology through the lens of gender and sexuality that exist outside of heterosexuality, serves as an antidote to heteronormativity in shaping how scientists examine and communicators interpret the environment (Interpretation4U 2020). Overall, these relational, racial, and sexual critiques of wilderness are intersectional and illustrate diverse perspectives that challenge norms about how wilderness is interpreted and communicated.

Reflective Assessment Process

Scholars recognize that the “social positions people occupy affect the meanings people ascribe to wilderness experiences and the role wilderness plays in their lives” (Meyer and Borrie 2013, p. 315). Further, scholars decolonize knowledge generation by legitimizing identity-centered lived experiences and other diverse ways of knowing (Goodrid 2018; Smith 2012). In April 2021, the Wilderness Institute convened a Wilderness Inclusivity Review Committee of 12 individuals whose social positions and lived experiences were essential to the committee’s work. To find appropriate and willing members for the committee, the Wilderness Institute asked longtime wilderness advocates and BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ speakers from previous National Wilderness Workshops for recommendations. The request asked for introductions to people, primarily those with current ties to wilderness advocacy or stewardship, who possess varied racial, gender, and ability characteristics that are underrepresented among wilderness professionals and visitors. These recommendations produced other recommendations in snowball sampling fashion, and ultimately 12 people volunteered to offer their expertise and perspectives as part of the review committee.

The committee membership included individuals with different and varied identity characteristics – African American, Indigenous, Latinx, AAPI, White, male, female, lesbian, Christian, educated, and having a disability – and diverse professions, social and age classes, and economic status – twentysome-things, early and mid-career professionals, and seasoned employees approaching retirement in the fields of wilderness stewardship, interpretation, higher education, and communications as agency employees, nonprofit volunteers, instructors, and students.

The review committee’s work was derived from the collective lived experiences of its members, their intergenerational familial customs and cultures, and relayed experiences from those within their social and professional circles. This followed the work of Goodrid (2018), Meyer and Borrie (2013), and Dietsch et al. (2021) where lived experiences across race, gender, and sexual identity revealed different perspectives in wilderness/human connections and outdoor recreation participation. Review committee members also collectively had both Western science and Indigenous knowledge backgrounds and viewed these as complementary lenses through which to examine the environment and conservation issues (Learn 2020; Smith 2012).

Initially, the review committee undertook an evaluation of select content on Wilderness Connect, a partnership project between the Wilderness Institute, Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center, and Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute. Wilderness Connect curates the predominant online wilderness resource library where more than 400,000 people (Google 2022) learn about wilderness annually. The evaluated content included a wilderness history timeline, a list of influential figures in the wilderness movement, and a biography of John Muir. The review committee evaluated this content both before and after proposed inclusive language editing. However, the review committee agreed after this initial evaluation that the committee’s scope required expansion to include a more detailed cataloging of exclusive communications elements, both in language and concept. Creating such a catalog could then guide future rewriting of interpretive content. The review committee agreed that identifying exclusionary elements of wilderness was a prerequisite to further developing a common understanding around challenges within wilderness communications. Thus, the themes that follow from the reflective assessment represent this important prerequisite step.

Wilderness Inclusive Communications Reflective Assessment

Consistent with diverse approaches to generating and legitimizing knowledge, in the following, we present the review committee’s cataloging of exclusive wilderness communications in the form of a reflective assessment that organizes distinct barriers to inclusive communications about wilderness under four key themes. Within each theme, we describe the barriers in detail to reveal why wilderness may be perceived as unwelcoming, undesirable, or unrelatable to individuals from systemically excluded groups. This work appears in its original form, authentic to the interpretations and knowledge cocreated by the review committee, with supportive literature included.

Wilderness History and Culture

Wilderness advocates often place the history of the wilderness movement as starting in the early 1900s with the formation of the Sierra Club, the damming of Hetch Hetchy Valley, and the rise to prominence of stars like John Muir. Others place wilderness history as beginning in the 1950s when Howard Zahniser began drafting the Wilderness Act of 1964. However, the social forces shaping the events during both time periods were set in motion centuries before. European settlement of the Americas; widespread Indigenous land dispossession and persecution; enslavement of African Americans; and subjugation of women, members of the Latinx and LGBTQIA+ communities, and other systemically excluded groups are important precursors recognized by the review committee that impacted the early wilderness movement and continue to influence wilderness culture. The following are exclusionary elements identified and discussed by the committee in relationship to wilderness history and culture.

Colonialism

Many, though not all, public lands, including what are now wilderness areas, are part of Indigenous peoples – as essential to existence as vital organs are to the human body. During early colonization of the country, land ownership under the Doctrine of Discovery – European nations having absolute rights to lands in the New World – was used to justify taking land – first, from Indigenous peoples who did not view land as property, and later, from Mexican and poor White settlers. Prior to becoming today’s public lands, these lands changed hands many times, often through force or coercion.

Other oppressive ideologies relevant to public lands have grown out of colonialism and Manifest Destiny including portraying Indigenous peoples and enslaved African Americans as savages and simpletons, subjugating them under the guise of necessary paternal guardianship, prioritizing the stories of settlers and pioneers, adopting utilitarian land–human relationships that place humans outside of and in control of nature, and creating a national identity centered around rugged individualism (Finney 2014; Gilio-Whitaker 2019; Henberg 1994; Smith 2012). Many of these oppressive ideologies suppressed and continue to eclipse long-standing land stewardship by Indigenous peoples and other systemically excluded groups.

Utilitarianism

Taylor (2016) connects colonialism with utilitarianism. She wrote that “White settlers saw the land as a commercial product” and themselves as “masters with dominion over it,” while Indigenous peoples viewed themselves as “custodians and stewards of the earth” (p. 11). Thus, wilderness can be referred to as a “resource.” Plant and animal contents have been cataloged according to the dominant norms of Western science. Lands are characterized by the benefits derived from or produced by them. Based on this norm, people and culture can be decoupled from wilderness, eclipsing the symbiotic relationship humans have had with land since time immemorial.

The review committee discussed how viewing wilderness as a “resource” has encouraged capitalistic itemization, valuation, and quantification. Such views also drove Indigenous land dispossession and have forced the loss and erasure of sacred connections to land and nature (Taylor 2016). Although early advocates championed protection of lands that they deemed had no economic value to extractive industry, we now have complex economic valuation systems that quantify in dollars the value of public lands for everything from ecosystem services to increases in private property values for properties near wilderness areas. Commodification of land, even in terms of nonextractive uses, such as recreation, frames land as a material object rather than as a self-determined subject.

Founding White Institutions of Conservation

In 1892, a small group of academics, scientists, artists, environmentalists, and students at the University of California formed the Sierra Club at a time when the university enrolled few women and no students of color. More than 40 years later, eight White men are credited with forming The Wilderness Society, despite women representing half of those in attendance at its first meeting. The history of the wilderness movement chronicles the formation of conservation institutions like these during post-reconstruction America when most, if not all, institutions were formed to be of service to Whites and excluded BIPOC.

Taylor (2016) described the evolution of today’s conservation movement, and by extension the wilderness movement, in the context of racism, sexism, class conflicts, and nativism through lenses of race and gender relations, power, and environmental identity (p. 9). The review committee discussed how early activists adhered to the inequity-containing prevalent social dogmas of the time and how a long history of gender and racial exclusion has resulted in organizations that largely continue to cater to and can be relevant only to privileged Whites.

Absence of BIPOC in Conservation

Conservation history has traditionally focused on deceased historical founders, many of whom were associated with founding White conservation institutions. BIPOC are largely absent from typical conservation narratives because they were excluded from participation in traditional conservation roles, or they did not fit into accepted definitions of what constitutes a conservationist (Finney 2014). As a result, their stories and historical connections to now-wilderness lands have been eclipsed.

The review committee discussed how these eclipsed connections often center sacredness regarding the natural world, an element that has largely been lost within conservation’s dominant view of nature as commodity. Further, on the one hand, conservationists often blame the poor and BIPOC for environmental degradation and biodiversity loss, and governments have long devised laws to criminalize traditional land use practices (Jacoby 2014; Taylor 2016). On the other hand, conservationists romanticize the relationships that BIPOC have with the environment, what has been referred to as ideas of the ecologically noble savage (Gilio-Whitaker 2019). This is particularly the case for Indigenous peoples whose relationships with and connections to land can be homogenized, stereotyped, and mischaracterized.

Seymour challenged the ways in which current environmental campaigns primarily use images of White, heterosexual, suburban, nuclear families to get people to care about environmental issues (Rachel Carson Center 2015). Finney (2014), Martin (2004), and White (2018) sampled and analyzed the prevalence and types of images of BIPOC in media sources like Outside, Time, and Ebony magazines and National Park Service brochures and digital guides. These studies show the same predominantly White outdoor recreation and environmentalist identity. Such practices have and continue to alienate BIPOC from early and current conservation efforts.

Culture of Conservation

Given the visibility of the White, privileged, colonial, and utilitarian origins of the wilderness and conservation movements, the review committee examined certain attributes that have become associated with identifying as a conservationist, environmentalist, and wilderness advocate, including serious, alarmist, arrogantly academic, grandiloquent, authoritative, pejorative, and dismissive of the lived experiences and cultural practices of others, among other negative descriptors (Seymour 2018, p. 17). Although often not explicit, these attributes set a particular clique tone within wilderness discourse and culture.

Specific to wilderness, advocates often elevate wilderness as the epitome of nature experiences and preservation status. These qualities have created exclusivity, meaning that the many other people who do worthy wilderness or conservation work may not want to identify as conservationists or wilderness advocates due to the off-putting and unrelatable attributes now associated with these labels. Even for those wanting the label of wilderness advocate, the review committee discussed how wilderness culture can expect one to follow an often unsustainable employment cycle that includes unpaid internships, multiple years of seasonal-only fieldwork, frequent relocation and isolation, and retiree and volunteer burnout. Especially for BIPOC, these attributes of wilderness job culture can be incompatible with values like family, stability, work-life balance, community, and home.

Foundational Wilderness Qualities

Wilderness advocates elevate the Wilderness Act, the singular law governing management of all US wilderness areas, as the gold standard for land protection. Indeed, the lands protected under the law provide sharp contrast to our increasingly built world. At a time of remarkable social, public health, and climate upheaval, the respite they provide is increasingly valuable. Yet, foundational concepts within the law drawing from colonial systems of thought – what Finney (2014, p. 47) described as underlying assumptions that presume a universality of White privileged ideals – can dismiss certain types of land–human relationships and perpetuate exclusive and narrow beliefs about what those relationships should look like. The review committee examined how these concepts can become barriers for systemically excluded groups.

Wilderness and Untrammeled Equal Unpeopled

The words “wilderness” and “untrammeled” are used within the Wilderness Act (1964) to define land as separate from people and have no equivalent concepts or translations in many non-English languages, including Indigenous languages. This can convey what is inherently a Western view of land–human relationships that largely erases Indigenous relationships with and Traditional Knowledge of lands that were originally ancestral homelands and remain essential to Indigenous identities and ways of life (Gilio-Whitaker 2020).

Purity

Although the word “pure” is not used in the Wilderness Act (1964), the concept of purity is suggested through language, including “unimpaired,” “man himself is a visitor who does not remain,” “land retaining its primeval character,” “affected primarily by the forces of nature,” and “imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable.” As with “wilderness” and “untrammeled,” the review committee explored how these words and phrases can collectively romanticize wilderness as an unadulterated landscape, perpetuate humans as “other,” suggest that humans sully the land, and prolong the myth of wilderness as unchanging and static, theories that are now seen as outdated by the scientific community.

A purist view of wilderness can perpetuate White dominance by negating and ignoring the role Indigenous peoples played in changing the landscape over time and their symbiotic relationships with the land. The review committee also examined how presenting wilderness as untouched by human hands can trigger the trauma of historical dehumanization that includes portraying Indigenous people as animals. Further, framing wilderness areas as vignettes of the natural world suggests human dominance over land, rather than acknowledging natural and climatic change and evolution.

Solitude

In accordance with the Wilderness Act, US wilderness management agencies purposely manage wilderness to provide opportunities for solitude, and many visitors seek it. Outdoor media feature solitude in recreation imagery. For some, solitude can be a bridge through which to connect with nature. Yet, for others, racial, gender, and economic systems of oppression can make valuing solitude difficult, inaccessible, or undesirable. Engebretson and Hall’s (2019) analysis of historical documents and hearings associated with the Wilderness Act suggests that remoteness, in terms of distance, absence of other people, and absence of the sounds of civilization, define the meaning of solitude. Yet, in a KIRO 7 News interview about African Americans in the outdoors, University of Washington social scientist Kathleen Wolf said, “This wilderness solitude thing seems very much to be a White Western European sort of preference. And that’s not shared by all cultures” (Sun 2022, para. 30).

Since solitude in wilderness is traditionally defined as a wilderness experience in the absence of other humans, this can suggest a mutually exclusive choice between solitude and shared experience. The review committee discussed how some people and cultures, instead, connect to nature in communal ways and don’t necessarily frame their experiences using normative wilderness vocabulary like “solitude.” People with disabilities connect to wilderness through shared experiences, although some strive for solitude. Further, solitude continues to evoke discomfort and fear for many women, members of the LGBTQIA+ community, and BIPOC, due to a long legacy of violence in the outdoors, continued harassment in the outdoors today, and varying cultural norms about groups, socialization, and criteria for safety.

Gender Assumptions

How some people understand and express gender is very different than it was in 1964 when the Wilderness Act was written. Although some cultures have long had much more malleable definitions of gender and gender roles, gender norms within the dominant American culture have evolved much more slowly. Definitions of gender and gender roles are more nuanced now and can be fluid. The review committee discussed how gender is no longer considered strictly binary or static, meaning that male and female are no longer the only choices with which to identify oneself. Separate and distinct definitions exist for sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and gender expression.

Exchanging pronouns (e.g., he/him, she/ her/hers, they/them, she/they, etc.) is becoming more common in social and work settings. This practice helps ensure that members of the LGBTQIA+ community define the language used to address them. Yet, “so much of conservation has been built on a toxic male model” (Bob Marshall Wilderness Foundation 2021, 22:22). The review committee considered how reexamining the traditional wilderness narrative, including historical and current assumptions about male-female binary roles, can increase inclusion for women, members of the LGBTQIA+ community, and a society that is embracing gender diversity.

Stereotypical Masculinity

Throughout the Wilderness Act, as we see in many other laws written in the past, the word “man,” for many, connotes able-bodied, cis-gender, White, Christian, middle- upper-class men, as opposed to humankind as it may have been intended. In the past, this was common practice, but today it can perpetuate a binary view of gender that excludes women, those who may not identify as either male or female, and those who may not identify as strictly male or female.

Language or media that elevates masculinity often does so by equating cis-gender, White males with ruggedness, ingenuity, individualism, and strength for wilderness travel (Mortimer-Sandilands et al. 2010; Olson 1938). Given that current conservation and wilderness culture is born of its history, Mortimer-Sandilands et al. (2010) suggested that wilderness remains a hetero- and hyper- masculine space where “ideals of whiteness, masculinity, and virility” are explored (p. 14). The review committee considered how this, coupled with continued use of the word “man,” can perpetuate a stereotypical cis-gender, White, male nature experience and connection involving manliness, vigor, prowess, and mastery over nature that marginalizes the experiences of those outside this stereotype.

Female Frailty

Women conservationists are still largely invisible within the traditional wilderness narrative despite their significant contributions. This is true for White women and even more pronounced for women of color, who face discrimination and erasure due to both gender and race. Although Kaufman (2006) and Reilly (2021) elevate unacknowledged women’s roles in the formation of national parks and wilderness areas, membership, leadership, and decision-making within early conservation efforts were dominated by men (Taylor 2002). The review committee discussed how women have been frequently described using language that characterizes them as “soft” and implies a nurturing rather than leadership role. Married conservation women, such as Mardy Murie, are still often referred to in context or association with their husbands, as opposed to acknowledging their distinct conservation roles separately. This leads to the erasure of many women’s contributions to the evolution of the wilderness movement.

Access to Wilderness

Access was defined by the review committee as connoting the degree to which a person feels welcome within wilderness and the ease or difficulty with which that person can visit wilderness. It includes, but is not strictly limited to, the physical act of entering or being within a wilderness area. Preferential, cultural, philosophical, educational, and financial aspects of access are parts of the definition and usage of the term.

Challenge

Challenge features prominently in wilderness marketing and media as a battle between people and the land, or more benignly as “roughing it” in the outdoors. Certainly, perseverance despite adversity, overcoming personal mental or physical barriers, and character building, are reasons many seek challenge in a wilderness setting. However, the review committee explored how challenge can also take a negative form in activities such as “peak bagging” that pit humans against nature and elevate an oppositional relationship definition, which can diminish Indigenous sacred views of land–human symbiosis. The ubiquity of seeking challenge in wilderness does not resonate with visitors who do not view challenge as enjoyable or desirable.

For some cultures, living with the land was and remains a way of life rather than a glamourized leisure activity (Taylor 2016). The review committee considered cases where camping, hiking, or swimming outdoors can instead conjure memories of family history rooted in trauma, such as tougher living conditions or poverty; incarceration in remote camps; field or hard labor; and lynchings related to immigration, mass African American migration from the rural South to cities during the mid-1900s, and escape to freedom in the North by enslaved African Americans using the Underground Railroad before and during the Civil War.

Ableism and Ageism

Wilderness recreation is predominantly a White leisure activity, and wilderness visitors are generally White, young, athletic, and adventurous (Martin 2004). As with age discrimination, disability has long been slighted within historical wilderness narratives and current public land recreation and management conversations (Cram et al. 2022). The review committee discussed how omitting the full spectrum of wilderness recreation experiences, appropriate assistive devices, and trails and settings that appear accessible may fuel assumptions that access to wilderness areas purposely excludes older visitors and outdoor enthusiasts with disabilities. When pictured, people with disabilities are often White, which excludes and others those BIPOC with disabilities by failing to recognize the intersection of racial and ability discrimination.

Classism and Education

Assumptions about class and education include base levels of knowledge, skill, and technology access that may not be understood or accessible by those of lesser means or schooling. Class and education are often closely linked and can intersect with race/ culture, ability, and gender to compound intentional and unintentional discrimination. The review committee considered topics like campsites, camping, hunting, and winter sports that often include a focus on gear, which assumes a certain level of knowledge about gear needed, how to use that gear, and the material means to purchase that gear. Online permit systems, another example, often preclude access by those on the disadvantaged end of the digital divide including people who cannot afford to pay for expensive broadband Internet services.

Further, the Outdoor Foundation (2021) reports that in 2020 46% of those who participated in outdoor recreation earned $75,000 or more annually, yet during the same year the average household incomes of African American and Hispanic families were $45,870 and $55,321, respectively (Shrider et al. 2021). Tellingly, travel distance, transportation, and travel costs were the top three reasons non-White survey respondents gave for not visiting national parks (Taylor et al. 2011).

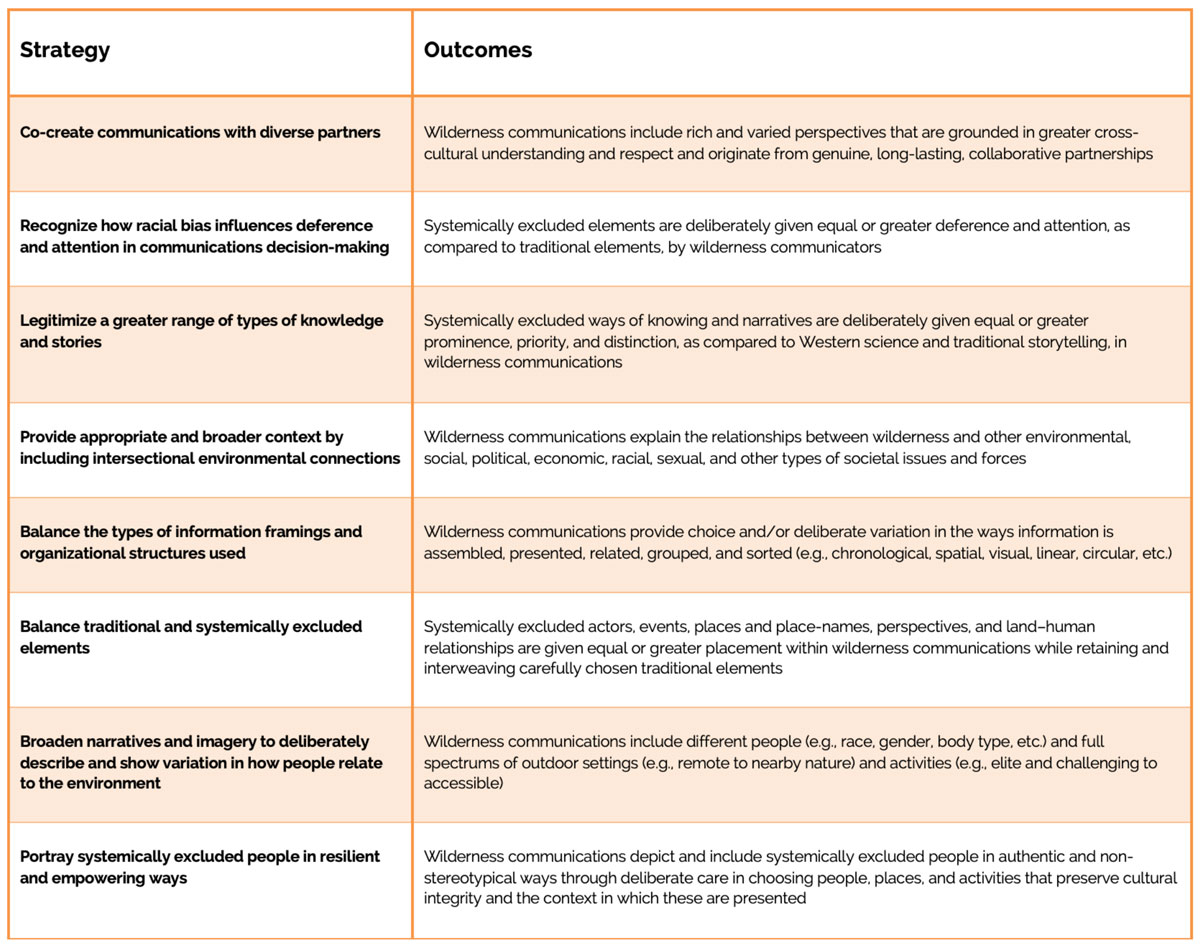

Figure 3 – 24th Infantry (Mounted), Yosemite Buffalo Soldiers (African American) near a road in the forest. Courtesy of Yosemite National Park.

Implications for Practice

Development and use of this reflective assessment are intended to help communicators identify barriers to inclusivity specific to wilderness. This assessment focuses on the scope of communications, which can influence formal and informal internal dialogue, relationships with partners, interactions with volunteers, outreach to the public, and some aspects of agency and institutional culture.

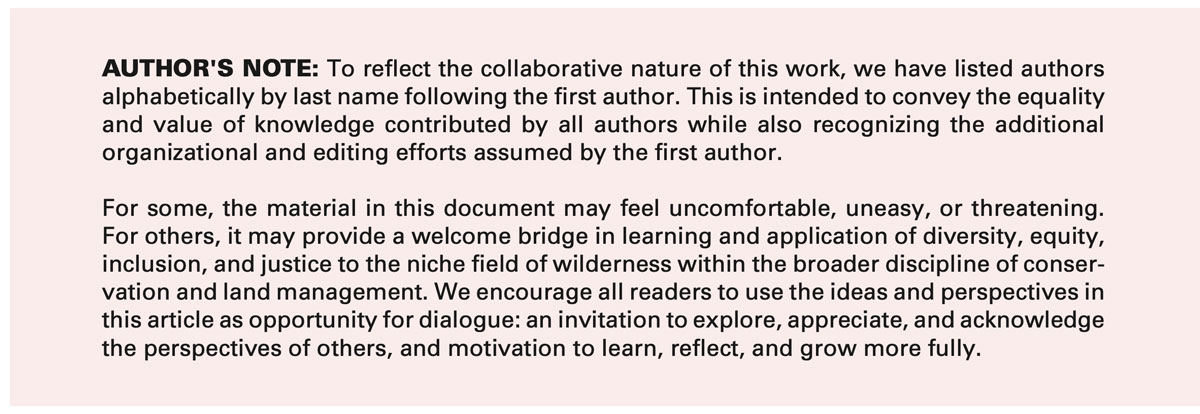

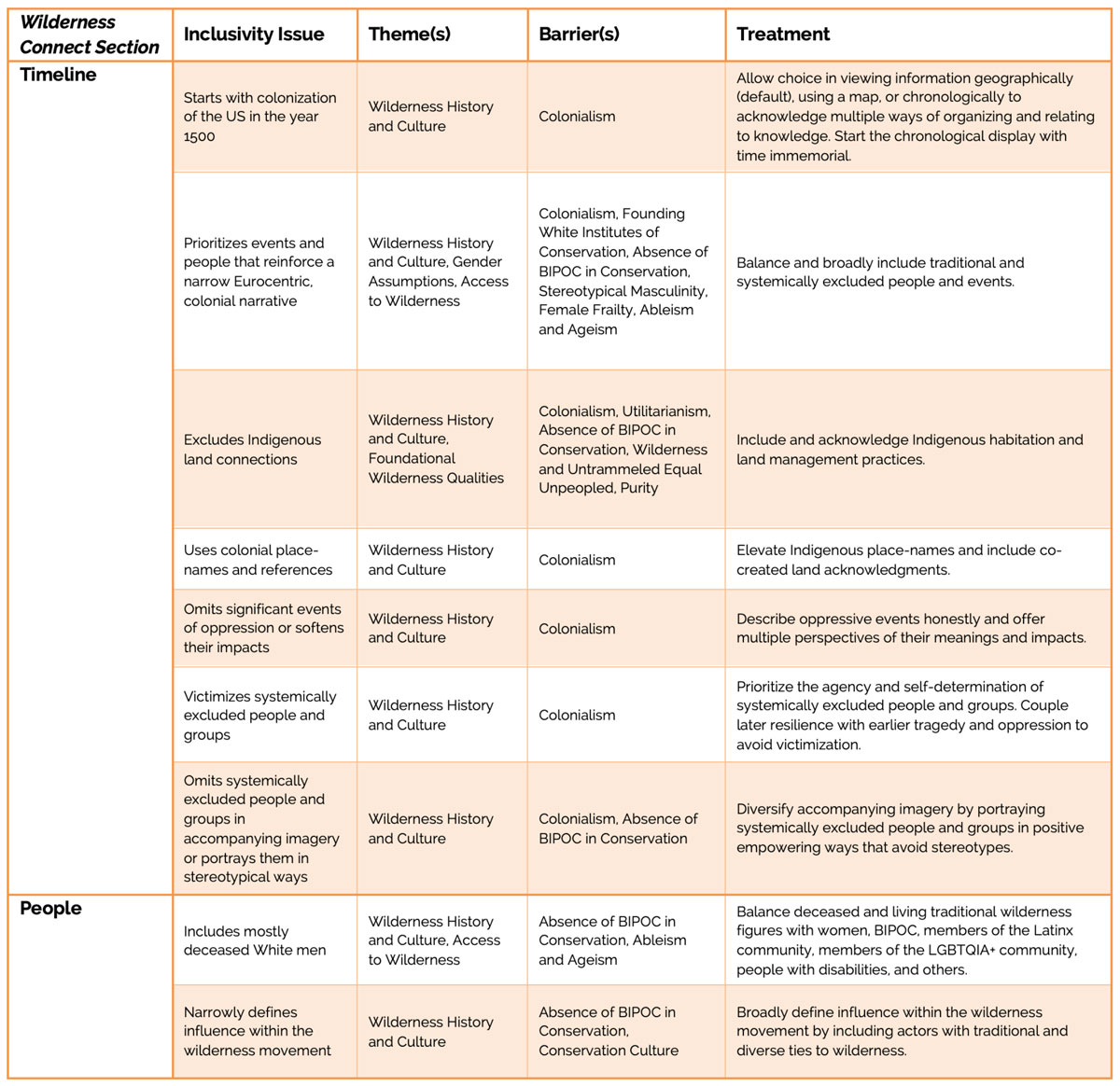

Understanding why systemically excluded groups may find wilderness unapproachable, unrelatable, undesirable, or offensive is a first step in evaluating the inclusiveness of existing communications efforts before exploring feasible options, alternatives, and changes. It is this understanding that the reflective assessment strives to provide. We now transition from understanding to application by first supplying a specific example from Wilderness Connect that links the themes and barriers from the reflective assessment to suggested treatments, followed by a summarization and generalization of overall treatments. Table 1 shows an analysis of select sections of Wilderness Connect, their connections to the four themes and barriers identified by the review committee, and suggested treatments. While not all themes and barriers are present in any single section on Wilderness Connect, the example application illustrates content that is barrier heavy and shows how barriers from multiple themes can appear simultaneously.

For example, the first three inclusivity issues identified in Table 1 (the first three rows) apply to Wilderness Connect’s timeline and are contained within all four themes and nine of the total 13 barriers. This historical timeline, accessed online in December 2022, spans the year 1500 to present and includes people, events, and imagery that chronicle the formation of the wilderness movement. The timeline focuses on able-bodied, White, male conservationists like John Muir and Gifford Pinchot and highlights events from colonizer stories, such as the settlement of Jamestown, Virginia, the founding of The Wilderness Society, and the creation of Grand Canyon National Monument. The timeline omits Indigenous land connections by describing land–human relationships from select colonial perspectives, such as in a quote from Daniel Boone crediting the settlement of Kentucky to its transition from a howling wilderness inhabited by savages and wild beasts to a fruitful field.

Table 1 – Analysis of inclusivity issues in two sections of Wilderness Connect accessed in December 2022, the relevant themes and barriers, and suggested treatments for the inclusivity issues.

In the last column of Table 1, the review committee suggests specific treatments for these inclusivity issues. First, the committee recommends a modified display featuring both geographically and chronologically organized information that allows viewers to toggle between the two display types – a timeline and an interactive map. Starting the chronological display with time immemorial better respects Indigenous land relationships, and presenting information by location better recognizes how some non-time-centric cultures organize information. In both geographical and chronological displays, including a richer selection of events, such as the founding of maroon communities in what are now North Carolina wildernesses (villages formed by escaped slaves in remote locations like swamps), expands a currently narrow narrative. Regardless of the display type, the content featured should balance traditional and eclipsed actors, events, and places. Yosemite National Park, for example, plays an important role as the place of inspiration for traditional conservationist John Muir and renowned nature photographer Ansel Adam, but it is also where the Buffalo Soldiers, African American soldiers that were part of the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry, became America’s first backcountry park rangers in 1866. Rewriting a currently colonial-heavy narrative to include systemically excluded people, places, and events alongside carefully chosen colonial actors could convey a history of wilderness that resonates with many perspectives. A more inclusive historical narrative should also acknowledge ancestral and current Indigenous homelands, recognize places and events of Indigenous significance, and include Indigenous place-names, such as Neníisótoyóú’u (Long’s Peak) within the Rocky Mountain National Park Wilderness. The review committee suggests the application of the treatments in Table 1 as methods for remediating exclusive communications largely by diversifying a currently homogenous narrative of wilderness history and the people who influenced it.

“Application of inclusive communications strategies can help communicators broaden traditional narratives about wilderness to respectfully include diverse stories and varied experiences.”

Inclusive Communications Strategies

Inclusive wilderness communications require incorporating content, definitions, and perspectives that are culturally relevant to systematically excluded groups (Sene-Harper et al. 2022). Application of inclusive communications strategies (Table 1) can help communicators broaden traditional narratives about wilderness to respectfully include diverse stories and varied experiences. Table 2 generalizes and summarizes treatments from Table 1 into inclusive communications strategies and outcomes that can be applied to any type of wilderness communications.

Discussions, dialogue, and active listening with different partners provide insights into the ways that systemically excluded groups relate to wilderness (or not) and how to best include their values through authentic descriptions of land–human relationships and nature. Smith (2005) suggested that “to discover such alternative understandings of wilderness we will need to look beyond the canonical nature writers” (p. 280). Lanham (Bob Marshall Wilderness Foundation 2021), Thomas (2022), Ybarra (2022), Finney (2014), and Reilly’s (2021) critiques of the absence of certain stories within the dominant wilderness narrative suggest wilderness communicators should expand beyond traditional actors to include more diverse voices. A long-term commitment to co-creating inclusive communications with diverse partners can ensure diverse voices are authentically and respectfully represented (Bob Marshall Wilderness Foundation 2021). We argue that an audit conducted by a group with rich and varied representation can reveal the identity characteristics, settings, and land– human relationships that are both prevalent and absent within interpretive materials and visual resource libraries.

Imagery in interpretive materials should deliberately include different people, background settings, and outdoor activities (Finney 2014; Martin 2004) and that Indigenous or noncolonial place-names should be used that support ongoing efforts to decolonize geographic naming systems (McGill et al. 2022; Necefer 2018). Communicators should learn to recognize how racial bias influences deference and attention (Levine et al. 2021) when choosing whose voices and places matter. Communicators should expand the types of knowledge deemed legitimate (Smith 2012) and acknowledge intersectional environmentalism (Intersectional Environmentalist 2021; Intersectional Environmentalist Council 2022; Thomas 2022). For additional sources, Kanigel (2019), the First Nations Development Institute (2018), and Younging (2018) provide language resources that promote respectful dialogue with and about systemically excluded groups, including appropriate terminology and nuanced conceptual advice for how to avoid common pitfalls like victimization and stereotyping.

Public lands and wilderness communicators hold incredible power over public perceptions and meaning derived from place. Communicators determine what social forces are related to wilderness and how those relationships are conveyed. Communicators influence whose stories are included or eclipsed and whether systemically excluded groups are portrayed as victims or resilient, tenacious, creative contributors. Communicators choose which publication and organizational formats (e.g., linear, nonlinear, chronological, spatial) to use and whether those formats respectfully and honestly portray diverse experiences. Finally, communicators control what information is distributed via which outlets. We hope that this work empowers communicators with resources and knowledge to make informed decisions and that it inspires commitment to exploring and understanding diverse perspectives about wilderness.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Land Management, US Fish and Wildlife Service, US Forest Service, or National Park Service.

Acknowledgments

We thank the two anonymous peer reviewers, the editor, and Wilderness Institute Director Andrew Larson for suggestions that improved earlier drafts.

About the Authors

LISA RONALD is the former wildlands communications director at the University of Montana’s Wilderness Institute where she oversaw Wilderness Connect for nearly 20 years. She now works for American Rivers; email: lronald@americanrivers.org.

SALAH AHMED is a visual information specialist and California interpretation and education lead with the Bureau of Land Management; email: saahmed@blm.gov.

KATIE BLISS is the deputy division manager in the Division of Training at the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Conservation Training Center. She formerly directed the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center and is a founding member of National Park Service Allies for Inclusion; email: katie_bliss@ fws.gov.

JESSE CHAKRIN is the director of the Yosemite Leadership Program; email: jchakrin@ucmerced.edu.

TANGY EKASI-OTU is the wilderness and Wild and Scenic Rivers specialist for the Forest Service’s Washington Office and former Hispanic Access Foundation fellow; email: tangy.wiseman@usda.gov.

KIMM FOX-MIDDLETON is the wilderness interpretation and outreach specialist at the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center. She is an Environmental Professionals of Color member and former diversity, equity, and inclusion trainer for the National Park Service’s Pacific West Region; email: kimm_fox-middleton@fws.gov.

JENN HARRINGTON is a Cree and Metis tribal member and Native American natural resource program coordinator at the University of Montana’s W. A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation. She is a former wilderness ranger; email: jennifer.harrington@umontana.edu.

SHELTON JOHNSON is a park ranger at Yosemite National Park. He is an author, poet, playwright, and actor in a stage production about Yosemite’s African American military history entitled “Yosemite through the Eyes of a Buffalo Soldier, 1903”; email: shelton_johnson@nps.gov.

TINA MAZZEI is a volunteer outing leader with the Sierra Club’s Gay and Lesbian Sierrans; email: tina_mazzei@yahoo.com.

JESSI MEJIA graduated in 2022 from the University of Montana’s Environmental Journalism Graduate Program. She is the former high country program coordinator at Glacier National Park and is now working as a freelance journalist and photographer; email: jessica.leigh.mejia@gmail.com.

ROGER OSORIO is a park ranger at Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument and former youth leader with Southern Appalachian Wilderness Stewards and Groundwork Hudson Valley; email: roger_ osorio@nps.gov.

References

Bob Marshall Wilderness Foundation. February 4, 2021. A new way into the wild: Inclusion as a criterion for the future of conservation (webinar). YouTube.

Brune, M. 2020. Pulling down our monuments. Sierra Club, July 22.

Cram, E., M. P. Law, and P. C. Pezzullo. 2022. Cripping environmental communications: A review of eco-ableism, eco-normativity, and climate justice futurities. Environmental Communication: 1–13.

Crenshaw, K. 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum (1): Article 8.

Davis, J. 2019. Black faces, black spaces: Rethinking African American underrepresentation in wildland spaces and outdoor recreation. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 2(1): 89–109.

Dietsch, A. M., E. Jazi, M. F. Floyd, D. Ross-Winslow, and N. R. Sexton. 2021. Trauma and transgression in nature- based leisure. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 3.

Engebretson, J. M., and T. R. Hall. 2019. The historical meaning of “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation” in the Wilderness Act of 1964. International Journal of Wilderness 25(2): 10–31.

Exec. Order No. 13985, 86 Fed. Reg. 7009 (January 20, 2021).

Finney, C. 2014. Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Out- doors. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

First Nations Development Institute. 2018. Changing the narrative about Native Americans: A guide for allies (white paper).

Fletcher, M., R. Hamilton, W. Dressler, and L. Palmer. 2021. Indigenous knowledge and the shackles of wilderness. PNAS, 118(40): 1–7.

Gilio-Whitaker, D. 2019. As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock. Boston: Beacon Press.

Gilio-Whitaker, D. 2020. The problem with wilderness, UU World, Spring 2020.

Goodrid, M. C. 2018. Racial complexities of outdoor spaces: An analysis of African Americans’ lived experiences in outdoor recreation. Master’s thesis, University of the Pacific.

Google. 2022. Analytics, Audience, June 6, 2021–June 5, 2022.

Graham, L. 2018. We’re here. You just don’t see us. Outside. May 1.

Graham, L. 2020. Out there, nobody can hear you scream. Outside. September 21.

Harmon, A. 2021. BIPOC or POC? Equity or equality? The debate over language on the left. New York Times, November 1.

Henberg, M. 1994. Wilderness, myth, and American character. The George Wright Forum 11(4): 41–51.

Interpretation4U. November 23, 2020. Rangers at Muir Woods interpret queer woods (video). YouTube.

Intersectional Environmentalist. March 15, 2021. The intersectional history of environmentalism (video). YouTube.

Intersectional Environmentalist Council. Retrieved 2022. Dismantle systems of oppression in the environmental movement.

Jacoby, K. 2014. Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation. University of California Press.

Johnson, C. Y. 1998. A consideration of collective memory in African American attachment to wildland recreation places. Human Ecology Review: 5–15.

Kanigel, R. 2019. The Diversity Style Guide. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Kaufman, P. W. 2006. National Parks and the Woman’s Voice: A History. University of New Mexico Press.

LaPier, R. 2021. Sustainable Missoula: Say goodbye to the words “wild” and “wilderness.” Missoula Current, August 23.

Learn, J. R. 2020. “Two-eyed Seeing”: Interweaving Indigenous knowledge and Western science. The Wildlife Professional, 14(4): 18–26.

Levine, S. S., C. Reypens, and D. Stark. 2021. Racial attention deficit. Science Advances. September 17.

Martin, D. C. 2004. Apartheid in the great outdoors: American advertising and the reproduction of a racialized outdoor leisure identity. Journal of Leisure Research 36(4): 513–535.

McGill, B. M., S. B. Borrelle, G. Wu, K. E. Ingeman, J. B. U. Koch, and N. B. Barnd. 2022. Words are monuments: Patterns in US national park place names perpetuate settler colonial mythologies including white supremacy. People and Nature: 1–18.

Meyer, A. M., and W. T. Borrie. 2013. Engendered wilderness: Body, belonging, and refuge. Journal of Leisure Re- search 45(3): 295–323.

Moon, K., and K. Pérez-Hämmerle. 2022. Inclusivity via ontological accountability. Conservation Letters, e12888.

Mortimer-Sandilands, C., R. Stein, B. Erickson, S. Alaimo, D. Bell, G. Di Chiro, A. Gosine, K. Hogan, G. B. Ingram, and L. McWhorter. 2010. Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire. Indiana University Press.

Necefer, L. 2018. Giving mountains back their Indigenous names. Outside. February 13.

Oglesby, C. 2021. The generational rift over “intersectional environmentalism”: Environmental justice gets a Gen Z makeover. Grist. February 10.

Olson, S. 1938. Why Wilderness? American Forests 44(9): 395–397, 429–430.

Outdoor Foundation 2021. 2021 outdoor participation trends report (white paper).

Race Forward: The Center for Racial Justice Innovation. 2015. Race reporting guide V. 1.1 (white paper).

Rachel Carson Center. October 9, 2015. Prof. Dr. Nicole Seymour on “bad environmentalism & heteronormativity” (video). YouTube.

Reilly, M. 2021. Beyond secretaries, hostesses, and cooks: The power, humility, and compassion of women who battled to save wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 27(1): 71–85.

Sene-Harper, A., R. A. Mowatt, and M. F. Floyd. 2022. A people’s future of leisure studies: Political cultural Black out- doors experiences. Journal of Park & Recreation Administration 40(1).

Seymour, N. 2018. Bad Environmentalism: Irony and Irreverence. University of Minnesota Press.

Shrider, E. A., M. Kollar, F. Chen, and J. Semega. September 2021. Income and poverty in the United States: 2020 (Re- port No. P60-273). United States Census Bureau.

Smith. K. K. 2005. What is African to me? Wilderness in Black thought, 1860–1930. Environmental Ethics 27(3): 279– 297.

Smith, L. T. 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd ed. Zed Books. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Retrieved 2022.

Social identities and systems of oppression.

Standing Bear, C. L. 1933. Land of the Spotted Eagle. Houghton Mifflin.

Sun, D. 2022. “Yes, Black people do hike”: Overcoming the diversity gap in outdoor recreation. KIRO 7 News. January 21.

Taylor, D. 2002. Race, class, gender, and American environmentalism (General Technical Report PNW-GTR-534). Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station.

Taylor, D. 2016. The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection. Duke University Press.

Taylor, P. A., B. D. Grandjean, and J. H. Gramann. 2011. National Park Service comprehensive survey of the American public, 2008 2009: Racial and ethnic diversity of National Park System visitors and non-visitors (Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/SSD/NRR-2011/432). National Park Service.

TED. July 2009. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The danger of a single story (video). YouTube. TED. October 2016. The urgency of intersectionality | Kimberlé Crenshaw (video). YouTube.

Theriault, D., and R. A. Mowatt. 2018. Both sides now: Transgression and oppression in African Americans’ historical relationships with nature. Leisure Studies 42(1).

Thomas, L. 2022. The Intersectional Environmentalist: How to Dismantle Systems of Oppression to Protect People + Planet. Voracious.

University of Montana. 2021. University of Montana diversity, equity, and inclusion plan (white paper).

White, T. 2018. The whitewashing of wilderness: How history and symbolic annihilation influence Black Americans’ participation at national parks. PhD diss., SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry.

Wilderness Act, 16 U.S.C. 1131-1136, as amended (1964).

Ybarra, P. S. 2022. The forgotten history of wilderness, and a possible future. High Country News, March 15.

Younging, G. 2018. Elements of Indigenous style: A guide for writing by and about Indigenous Peoples. Brush Education.

Read Next

Unseen Forces Still Wild

Between the precincts of Amun-Re and Montu in the vast Egyptian temple complex of Karnak is a dark little room permitting only a single shaft of sun- or moonlight to enter.

Kathy MacKinnon

A Smart, Dedicated, Accomplished, and Compassionate Conservationist

Wilderness Perspectives: Zahniser’s Support for the Authentic Wilderness Experience

When many of us picture Howard Zahniser, we think of one image. With a focused look on his face, we see Zahnie looking directly into the camera in his backyard in Hyattsville, Maryland, wearing a custom-tailored suitcoat.