Photo credit: Trenna Sonnenschein from Pixabay

Shifting Baseline Syndrome among Whitewater Outfitters and Guides

Implications for Conservation and Wilderness-Focused Enterprises

Communication + Education

June 2023 | Volume 29, Number 1

The COVID-19 pandemic reintroduced people to semi-wild lands and bona fide wilderness as a way to achieve refuge from society-induced lockdowns and self-quarantine (Hans- man 2020). For many, the pursuit of outdoor adventures in the pandemic/post-pandemic era represented a refreshing return to past experiences such as camping under the stars, hiking a trail, birding around an alluring lake, rafting a frothing river, or another activity they were accustomed to away from home (Rice et al. 2020). For others, their path to the outdoors was entirely new and by no means a “reintroduction.” These new sojourners inevitably appreciated wildness and the natural environment in a new light; an experience not related to a past observed baseline but rather informed by various facts, false- hoods, attitudes, myths, and legends about wildness conveyed in the media and on the internet as well as by social communication among family, friends, and acquaintances (Watkins 2021).

Biological degradation and widespread habitat loss driven by climate change coupled with heightened population impact are challenging the very integrity of wilderness. Less outdoor-experienced visitors may not be as sensitive to these environmental changes due to so-called generational amnesia (Jones et al. 2019) where prior generations’ knowledge vanishes when younger generations are not informed, lack pertinent experiences, or otherwise overlook key information that older generations attempt to transmit to them. More outdoor-experienced people may also suffer a type of personal amnesia as they attempt to cope with environmental change (Papworth et al. 2009). It may be easier, even necessary, for outdoor-experienced people to conveniently forget details about prior environmental conditions simply to cope with the current environmental changes confronting them. Together these generational and personal forms of amnesia can be conceptualized as a “shifting baseline syndrome” (hereafter SBS); that is, biological change is inaccurately perceived. In essence, when SBS is present, people tend to see biological change as less severe or interpret gradual change as an accepted norm. The condition of the natural environment is misinterpreted due to the lack of information, perspective, or experience with past conditions. Most importantly, the existence of SBS engenders a dilemma that threatens society’s ability to address conservation and environmental crises.

SBS initially was explored from the perspective of fisheries and ocean ecology (Pauly 1995) as well as landscape architecture (McHarg 1969). Eventually, SBS became generalized to represent widespread change affecting society (Olson 2002). Although SBS has deep roots in ecology, conservation, and wilderness-related literature, limited understanding exists about the impact of SBS on those professionals and outdoor providers who safely guide the public through the vicissitudes of wilderness travel and experience. Research has almost exclusively used a public-level natural resources/conservation focus while eschewing interest in commercial operators and concessionaires. It can be argued that those working in environmental- and conservation-related enterprises/ entities should be the least likely candidates to experience either generational or personal amnesia linked to SBS. However, the SBS literature highlights that stakeholders active in the environmental and conservation arenas are equally susceptible to the “extinction of experience” (Hathow et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2011; Soga and Gaston 2018) and may develop an increased tolerance for degraded conditions (Bilney 2014; Pauly 1995; Vera 2010).

Arguments can be made about the resistance of SBS developing in wilderness outfitters, guides, rangers, resource managers, and others. On the one hand, they can be intimately connected with the natural environment and thus personally witness the realities of environmental and biological changes occurring around them. With frequent field experiences, they should be less likely to develop SBS because of their immediate awareness of environmental change, however subtle it may be. On the other hand, person- ally intense environmental perceptions can erode over time as constant challenges to the environment accumulate. These professionals and practitioners may gradually adapt their perceptions to accommodate changes that they are forced to accept over time.

This article explores the SBS phenomenon among whitewater guides and outfitters and examines the implications for wilderness stewardship and conservation. Competitive business strategies used by Colorado whitewater outfitters to maintain their firms’ sustainability were studied longitudinally to ascertain the extent of change. Shifts in essential business strategies such as protecting client safety, expanding services/products, and maintaining websites as a key marketing effort were examined from the perspective of SBS; specifically, how and in what ways outfitters respond to mounting environmentally related challenges in the whitewater rafting sector relative to these strategies.

If concessionaires/outfitters are progressively compromising on key business processes such as internet design and content, service expansion, or service quality due to coping with persistent SBS-related environmental pressures, it may be appropriate for them, professional associations, governmental agencies, and advocacy groups to consider possible remedies, enlightened policies, and supportive assistance. This study’s findings regarding whitewater outfitters may offer preliminary evidence about the need to build an agenda of interventions that address SBS-related erosion of recreational experiences by conservation professionals and wilderness stakeholders.

Studying Shifting Baseline Syndrome

The state of Colorado has diverse and vibrant river systems as well as very active and well- regarded outdoor professional associations advocating for members. For example, the Colorado River Outfitters Association (CROA) represents approximately 50 members who benefit from the organization’s political advocacy and technical assistance. CROA’s website (https://www.croa. org/) gives the public an opportunity to choose among outfitters who serve 20 rivers. In addition, the website provides access to video tutorials on whitewater safety, river comfort, river ratings, and river management agencies. CROA offers an annual convention for its members focusing on key current topics such as river licensing, pricing, and risk management, and it sponsors an “Annual Commercial River Report” containing a wealth of information about river use and economic indices. In sum, due to its advocacy and member support, CROA creates a strong setting for investigating the SBS among whitewater guides and outfitters.

Website assessment is a prevalent research approach in the recreation, hospitality, and tour- ism fields (Ip et al. 2011). To explore the influence of SBS among whitewater guides and outfitters, the websites of 44 Colorado whitewater rafting firms were examined in 2005 and 2022.

Figure 1 – Raft master’s guided whitewater rafting on the Arkansas River through the Royal Gorge in Canon City, CO. Photo by Jackalope West on Unsplash.

The overall framework for this study draws from classical business literature (cf. Porter 1980; Hart et al. 2003) underscoring that firms respond to changing external pressures by altering their competitive strategies and tactics to remain profitable. For example, when the outdoor action camera industry grew rapidly from 2005 to 2015 with the advent of GoPro’s “Hero” line, competitors shifted their business strategies by rapidly adding features (product diversification), offer- ing applications (service diversification), and lowering prices (value proposition management) to address the technological disruption. Nonetheless, by 2016 the industry was in rapid decline because the external environment changed dramatically as smartphones gave customers not only an excellent camera but also a direct connection to social media for sharing video content. The disruption for action cameras is in many respects analogous to rapid climate change that now confronts whitewater rafting firms and thus could be creating SBS.

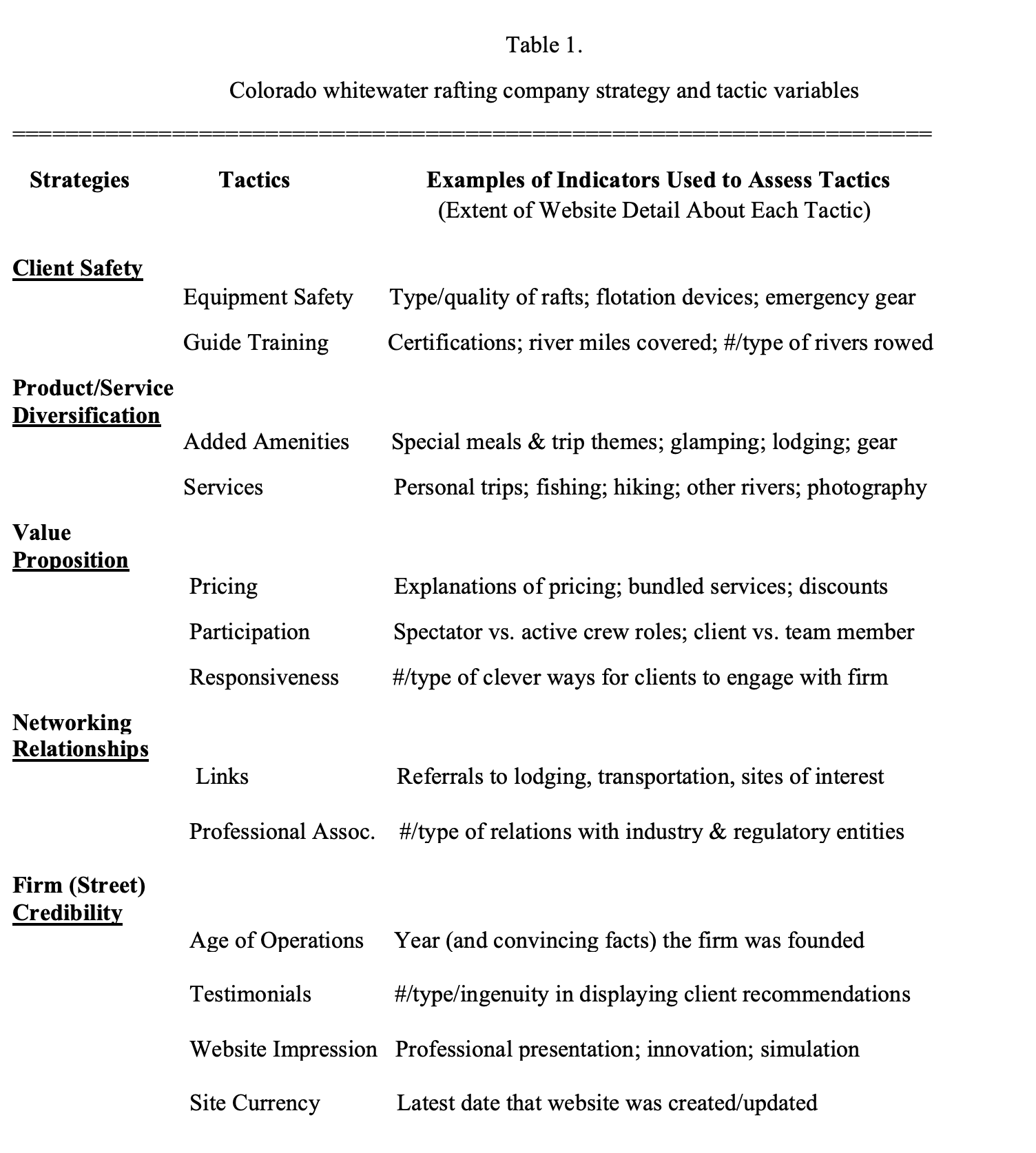

The investigation focused on five strategies with accompanying tactics that operationalize each strategy shown in Table 1. Outfitters utilize three main strategies: safety (e.g., they maintain a clean record for accidents and client injury/death), product/service diversification (e.g., they add amenities to their trips such as gourmet meals and kayaking), and value proposition management (e.g., they lower costs and prices to give more value) to attract more whitewater clients and thus achieve sustainability. Outfitters and guides use two additional strategies in trying to attract clients: networking relationships (they form partnerships with various corollary recreation/hospitality entities such as inns, motels, and restaurants to support clients), and firm credibility (e.g., they use brochures, websites, and associated information dissemination to embellish clients’ knowledge about their firms essential for informed consumer purchase decisions). As rapid climate change increasingly takes attention from outfitters, they may either shift their perceptual baseline to lower their concern about the change (i.e., enact SBS) and/or they may redirect attention from managing their strategies/tactics to the climate change thus neglecting best business practices (and in the process creating business-centric SBS).

Tactics related to firm strategies were analyzed (verified by two of the authors to ensure reliability) for change over time. These tactics were assessed utilizing information presented on each firm’s website and assign- ing a value using a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly not present/disagree; 7 = strongly present/agree) based on prior research methodology (Kline et al. 2005; Crawford et al. 2013). As an illustration, with respect to the tactic of equipment safety, each firm’s entire website was studied to identify specific references to the type of rafts that are used and explanations regarding why those rafts are advantageous (e.g., not only for having fun when running a river but also ensuring that cli- ents would survive catastrophes such as “flips” or “swims”). Equipment was broadly defined to include personal flotation devices, emergency equipment (e.g., satellite telephones), accompanying guide kayaks to assist in rescue, and assorted gear that may not be required by regulatory bodies but is indicative of prudent concern about client safety.

It is informative to note that in 2005, 44 firms were assessed compared to 37 firms in 2022 due to fewer firms listed by the CROA. Possible explanations for attrition include consolidation among firms, inconsistent river flows due to climate change that chase firms out of business, the pandemic in 2020–2021, growing regulatory constraints (e.g., permitting limitations), economic and financial factors, and generational changes (e.g., outfitters retiring from the business).

Results

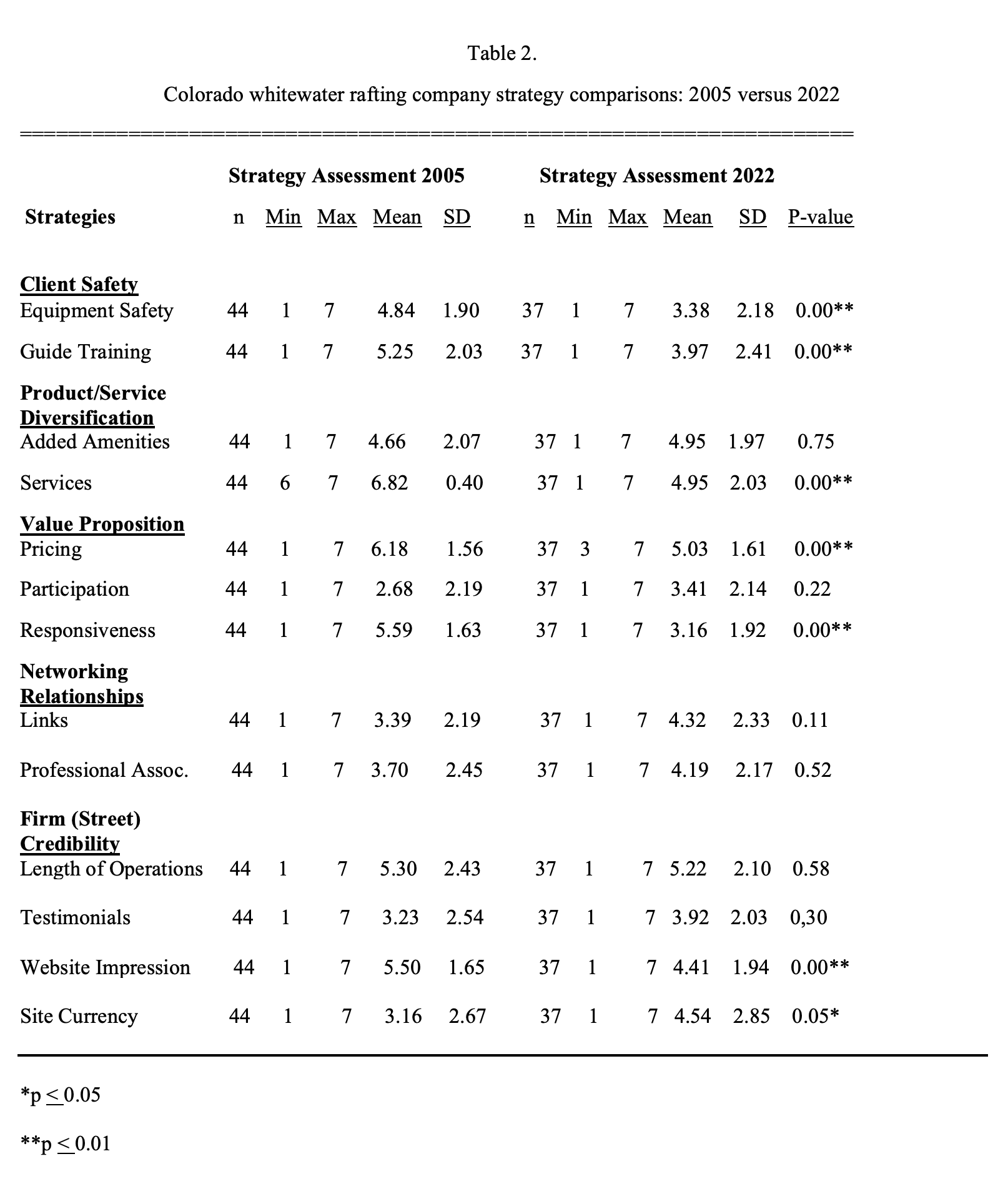

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the assessment of each whitewater firm’s strategies and tactics during 2005 and 2022. The 2005 data indicate that the firms were rated highly (using the seven-point scale: >4.50) on 8 of the 13 (61.5%) tactics, especially regarding service diversification (6.82) and pricing (6.18). The firms were rated lowest in 2005 for client participation (2.68), website currency (3.16), use of testimonials (3.23), and sharing links to other important related organizations (3.39). Overall, the firms were rated highest for strategies pertaining to client safety, product/ service differentiation, and value proposition.

A different overall impression surfaced for the 2022 data. The highest ratings (using the seven-point scale: >4.50) for tactics included length of operations (5.22) and pricing (5.03) along with added amenities (4.95), service diversification (4.95), and site currency (4.54). The product/service diversification strategy had two tactics that were rated as relatively high (4.95). The lowest-rated tactics were firm responsiveness to client queries (3.16) and equipment safety (3.38). A total of 8 of 13 tactics were rated as neutral (4.00) or higher in 2022, equivalent to the 2005 assessment. Only 5 of 13 (38.5%) firms recorded ratings greater than 4.50 in 2022 compared to 8 of 13 (61.5%) in 2005. By contrast only two tactics, client responsiveness (3.16) and equipment safety (3.38) in 2022 were rated equal to or below 3.39 versus the four lowest-rated tactics in 2005 (i.e., client participation, website currency, use of testimonials, and sharing links).

The average mean score for the 13 tactics in 2005 is 4.61 compared to an average mean score of 4.27 in 2022, suggesting that the whitewater rafting firms were not extensively maintaining their websites (i.e., updating/ improving existing content, integrating new information, redesigning the site, incorporating technological innovations, building client relationships, and promoting ease of access). Diminishing maintenance can erode website effectiveness as far as convincing readers/ prospective clients about safety, product/service diversification, value proposition, network relationships, and firm credibility. Decreasing attention to website effectiveness is captured quite clearly as 6 of the 13 (46.2%) tactics in 2022 were rated lower than in 2005 at a level of statistical significance p <0.001: equipment safety, guide training, service diversification, pricing, client responsiveness, and website impression.

Table 1 – Colorado whitewater rafting company strategy and tactic variables

Table 2 – Colorado whitewater rafting company strategy comparisons: 2005 versus 2022

Alarmingly, the greatest consistent decline in tactics occurred for client safety and value proposition, tactics that are certainly very important to clients who want good value for their dollar while at the same time seeking a safe float. Clients who have never rafted a river before, or never floated a particular river usually have active anxiety about what to expect and whether they will return safely. Outfitters have to assuage this anxiety in order to secure the person as a paying customer. An effective way to temper this anxiety is by informing them through web content, video clips of safety equipment/procedures (à la CROA’s video clips), and client testimonials. Value is a preeminent concern among customers in the tough economic times fostered by the pandemic. Whitewater rafting firms are challenged to convince customers that they will derive the most fun and adventurous memory for their dollars.

Only one tactic rating (7.7%) is improved in 2022 compared to 2005 at a statistically significant level: site currency (p<0.05). This result suggests that whitewater rafting firms in 2022 were doing a better job of document- ing that their website is current compared to 2005. However, documenting website currency is not the same as extensively maintaining website content, integrating technology, facilitating access, stimulating internet client relations, or website redesign. It should be noted that 5 other tactics (38.5%) recorded improved scores but not at a statistically significant level. Thus, 46.2% of the firms were rated as showing improvement in their 2022 tactics compared to 2005 but not at an acceptable statistical threshold.

Figure 2 – Photo by Kelly Wood on Unsplash.

Colorado whitewater rafting firms showed greater erosion in their tactics rather than improvement for 2022 compared to 2005. A total of 6 tactics showed declines at a statistically significant level while 5 displayed improvements. From a practical viewpoint, the 2022 results merit concern. Three of the firms’ five most important strategies related to client safety, product/service diversification, and value proposition appear to have declined. The very essence of a sustainable business model for wilderness-focused enterprises hinges on client safety, product/service diversification, and a viable, as well as competitively functional, client value proposition. In sum, these results deserve careful attention from whitewater rafting firms as they address the substantial challenges facing every wilderness- and conservation-focused enterprise and institution.

Implications for Wilderness Outfitters and Guides

That whitewater firms appear to be neglecting intrinsic enterprise strategies is not all that surprising because people tend to like doing that which they do best (Buckingham 2005). Running rivers, not managing the internet, is consistent with the rugged individualism of American guides and outfitters. On the other hand, their hard-working lives become much more difficult when the businesses they have guided suddenly go out of business. At those moments they realize that attrition is possible in their competitive business environments. This finding appears to be substantiated by the fact that 16% fewer members of the Colorado River Outfitters Association firms operating in 2005 were conspicuously absent 17 years later in 2022.

Attention to good business practices, such as website maintenance and redesign, is an effective way for firms to remain solvent. The internet offers one of the very best value propositions for marketing and building fruitful connections with clients, both past and prospective. Consequently, this study’s results imply that degraded/declining internet presence by whitewater firms is a powerful motivation to rethink how investments in websites can pay impressive returns. Most whitewater personnel are out in the field during rafting season while their websites dutifully inform client perceptions despite their absence. Even though outfitters may not enjoy managing their websites, few other options are available that possess such a high payoff as far as attracting and retaining clients.

Client safety, product/service diversification, and managing the client’s value proposition form three pillars for successful business strategy among whitewater firms. This study suggests that Colorado whitewater firms could improve the content of their websites that conveys facts and detail about equipment safety and guide training. Within the website analysis, it was easy to distinguish between those firms that made a strong case for client safety and those that did not. Moreover, many firms failed to communicate and underscore the underlying value proposition associated with their pricing. Younger clients are typically very savvy in using websites to com- pare competitors. Firms in this study could do a better job in explaining why their prices offer value for clients, and they could improve on enabling clients to connect with them. Whitewater firms could be more enthusiastic about making a deeply personal connection with clients, a relationship that is more than simply digital.

“Perhaps foremost is the realization that the phenomenon of shifting baseline syndrome may be impacting the outfitter and guide industry in subtle but often significant ways.”

Implications for Wilderness-Focused Enterprises and Public Conservation

Although this study’s findings have practical significance for wilderness outfitters and guides as far as competitive strategy and long-run business sustainability, the results also suggest inherent concerns about the future of wilderness experiences and conservation. Perhaps foremost is the realization that the phenomenon of shifting baseline syndrome may be impacting the outfitter and guide industry in subtle but often significant ways. This study raises a question about why whitewater firms are not doing a better job of investing in their main website connection to the public and prospective clients. Is this change explained by SBS? Are professionals in the outfitter and guide industry devoting mental and physical resources to coping with environmental and natural resource change to the detriment of operating their business effectively? Additionally, are conservation and natural resources personnel correspondingly susceptible to SBS?

The many dedicated people who invest themselves in recreational-centered careers, resources management, and outdoor employment face a difficult predicament. Most are devoted to protecting and preserving wildlands at a time when global changes are occurring with greater frequency and much deeper magnitude. Yet these ardent agents have virtually few, if any, resources or discernible strategies for addressing the very problems that loom over them. How long have they been fighting to protect and preserve our forests, mountains, oceans, deserts, rivers, swamps, and Earth? Earth Day began on April 22, 1969. Since that milestone alone, public sensitivity about environmental degradation has been present for more than 50 years. And despite the many victories that have occurred in the intervening 50-some years, powerful, formidable challenges continue to exist.

What about people who have joined in conservation and environmental battles through advocacy, professional management, or as described in this study, as wilderness- and conservation-focused enterprises? What sort of damage and attrition have occurred to them over these decades? Some have experienced burnout and/or possibly post-traumatic syndrome due to drastic environmental changes (Legault 2020). Others may gradually fall prey to SBS whether as a means to cope with the pressures they face or by the necessity to achieve equilibrium with their coworkers or the public they serve. This study’s findings about enterprise strategy devolution by Colorado’s whitewater rafting guides and outfitters may be illustrating the indirect consequences of SBS. For a host of reasons mentioned earlier, the principals in these firms may experience a form of personal amnesia and neglect of intrinsic enterprise strategies in order to cope with acknowledging an environment that is depressing and constrained.

This study’s findings appear to discover the presence of SBS among Colorado whitewater outfitters and guides as an explanation for devolving business strategies associated with their firms. From 2005 until 2022 the data show decreasing emphasis on fundamental strategies that are most related to sustain- able enterprises – attention to consumer value proposition, safety, and credibility. This decrease occurs at precisely the time that rather ominous external pressures are increasing such as climate change affecting river systems, economic inflation, and pandemic- driven suppression of client demand. Normally when encountering such threats enterprises increase their attention to, and emphasis on, the most fundamental strategic pillars essential to financial sufficiency. However, the opposite trend was found in this study.

Decreased attention on these fundamental business strategies may be associated with the accumulated stress or pressures accompanying environmental changes in recent years. In this respect, widespread climate change directly affects rafting firms’ ability to operate at previous operating levels. As climate change persists it is entirely plausible that outfitters’ attention drifts from their business operations to continuing intractable climate problems. Essentially, whitewater guides and outfitters have limited means of controlling these global forces, so they gradually cope, resulting in a shifting baseline about the weather/climate as well as about inherent business practices in their firm.

Outfitters and guides in this study may also be experiencing generational amnesia; that is, they are not effectively passing their more traditional environmental perceptions to recent professional generations. Generational amnesia implies that new age groups may not be able to conceive of the sublime beauty in rafting down Glen Canyon because they cannot remember or reminisce about what they have not experienced. As elders pass on, new generations lose this memory. If new professional cohorts were able to resurrect or embrace the memories, their baseline might be different from that which they presently experience; their baseline might not shift.

The SBS concept also suggests that outfitters and guides could lose interest in altering their practices because it undermines the rationale to continually revise how they guide, or how their firms conduct business. And when it comes to website design and content, outdoor-focused individuals are more likely to emphasize what they love … rafting rivers rather than managing technology at the home office. Thus, the existence of SBS may not only be significant at the client level but at the guide/outfitter/firm level as well.

Public conservation is at risk when the greater population displays a form of amnesia about how environmental degradation has occurred over the years. Many have capitalized on this amnesia to promote a rosy future about global climate change that now increasingly appears to be catching up with us. By the same token, our ability to safely raft Wild and Scenic Rivers is on the threshold of collapsing as too many want access to what has become too little due to global climate change. In the balance hangs the entirety of conservation and our planet.

We are at a seminal crossroads moment. Currently every potential whitewater client can still dream of someday adventuring to Colorado to experience a thrilling ride through Class 4 and 5 rapids. This dream exists because Wild and Scenic Rivers and lakes belong to all of us, whether we live on a 100-acre ranch or in a rented room. These water resources are a bedrock institution in the US, as critical as the US Bill of Rights.

Understanding SBS can often seem abstract. But, with our current threats to reduced resources, outfitters and clients must decide whether to maintain our powerful natural resource base and whitewater experiences for all or to relegate this unique participatory opportunity to the wealthy and well-connected. The time to decide is now. In the balance hangs the entirety of whitewater rafting, conservation, and our planet.

About the Authors

HOWARD L. SMITH is a professor in the Milgard School of Business at the University of Washington Tacoma; email: smithhl@uw.edu.

RICHARD DISCENZA is a professor and dean emeritus at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs; email: rdiscenz@uccs.edu.

ROBERT G. DVORAK is editor in chief of IJW and professor in the Department of Recreation, Parks, and Leisure Services Administration at Central Michigan University; email: dvora1rg@cmich.edu.

MICHAEL TUREK is an assistant teaching professor of Business Analytics at the Milgard School of Business, University of Washington Tacoma. Michael serves as director of analytics programs and is an associate director for the Milgard Center for Business Analytics; email: turekmd@uw.edu.

References

Bilney, R. J. 2014. Poor historical data drive conservation complacency: The case of mammal decline in south-eastern Australian forests. Austral Ecology 39, 875–886.

Buckingham, M. 2005. What great managers do. Harvard Business Review, March. https://hbr.org/archive-toc/ BR0503.

Crawford, A., C. S. Deale, and R. Merritt. 2013. Taking the pulse of the B&B industry: An assessment of current marketing practices. Tourism and Hospitality Research 13(3):125–139.

Hansman, H. 2020. The outdoors needs more people – But less of them. Sierra Magazine. https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/2021-1-january-february/feature/covid-19-chance-reframe-how-we-use-and-abuse-public-land.

Hart, S. L., and M. B. Milstein. 2003. Creating sustainable value. Academy of Management Executive 17(2): 56–69.

Hathow, D., M. A. Eaton, A. Stanbury, F. Burns, W. Kirby, N. Bailey, and N. Symes. 2019. The state of nature 2019. The State of Nature Reports. The State of Nature Partnership.

Ip, C., R. Law, and H. A. Lee. 2011. A review of website evaluation studies in the tourism and hospitality fields from 1996 to 2009. International Journal of Tourism Research 13: 234–265.

Jones, L. P., S. T. Turvey, D. Massimino, and S. K. Papworth. 2019. Investigating the implications of shifting baseline syndrome on conservation. People and Nature 2: 1131–1144.

Kline, S. F., A. M. Morrison, and A. S. John. 2005. Exploring bed & breakfast websites: A balanced scorecard. Journal of Travel & Tourism 17: 98–102.

Legault, S. 2020. Taking a Break from Saving the World. Victoria BC: Rocky Mountain Books.

McHarg, I. 1969. Design with Nature. Gloucestershire, UK: The Natural History Press, 67–70.

Olson, R. 2002. LA Times opinion piece. http://www.shiftingbaselines.org/op_ed/index.html.

Papworth, S. K., J. Rist, L. Coad, and E. J. Milner-Gulland. 2009. Evidence for shifting baseline syndrome in conserva- tion. Conservation Letters 2: 93–100.

Pauly, D. 1995. Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 10: 403.

Porter, M. 1980. Competitive Strategy. New York: Free Press.

Rice, W. L., T. J. Mateer, N. Reigner, P. Newman, B. Lawhon, and B. D. Toff. 2020. Changes in recreational behaviors of outdoor enthusiasts during the COVID-19 pandemic: Analyses across urban and rural communities. Journal of Urban Ecology 6(1): jua020.

Soga, M., and K. J. Gaston. 2018. Shifting baseline syndrome: Causes, consequences and implications. Frontiers of Ecology and the Environment 16(4): 222–230.

Watkins, A. 2021. Pandemic wilderness explorers are straining search and rescue. New York Times. nytimes. com/2021/04/07/us/coronavirus-wilderness-search-rescue.html.

Vera, F. 2010. Chapter 9: The shifting baseline syndrome in restoration ecology. In Restoration and History: The Search for a Usable Environmental Past, 1st ed., ed. M. Hall (pp. 116–128). New York: Routledge.

Wu, T., M. A. Petriello, and Y. S. Kim. 2011. Shifting baseline syndrome as a barrier to ecological restoration in the American Southwest. Ecological Restoration 29(3): 213–215.

Read Next

Unseen Forces Still Wild

Between the precincts of Amun-Re and Montu in the vast Egyptian temple complex of Karnak is a dark little room permitting only a single shaft of sun- or moonlight to enter.

Kathy MacKinnon

A Smart, Dedicated, Accomplished, and Compassionate Conservationist

Can We Make Wilderness More Welcoming?

An Assessment of Barriers to Inclusion