Arabian gazelles and acacia trees in Al-Saleel Nature Park.

Tapping into Oman’s wealth beyond its oil: Developing nature – based tourism in the Sultanate’s wildlands

International Perspectives

April 2022 | Volume 28, Number 1

Oman’s dramatic beauty – juxtapositions of blue seas, golden deserts, marbled mountains, and verdant canyons – beckons for nature-based tourism (NBT) (Figure 1). Like many other countries, Oman is examining how to adapt to changing economies and considering how natural resources and NBT fit into this adaptation. Thus far, Oman’s economy has prospered mainly from developing its petroleum reserves. However, petroleum-dependency is not sustainable, by the mere fact of oil’s finite nature, nor does it appear to be resilient, given the global shift toward other energy sources. This presents a conundrum for Oman and other countries in a similar position of how to diversify while still upholding the quality of life that such a rich economy has provided.

Figure 1. A sample of Oman’s dramatic and diverse natural beauty: coasts, deserts, mountains, and canyons.

For Oman and Omanis in particular, part of the answer may relate to the relative recency of petroleum exploitation and national development and include advertising the country’s currently undeveloped, substantial wildlands as attractive for tourism generally and NBT in particular (Buerkert et al. 2010). The country was relatively undeveloped in infrastructure until the 1970s, when the late Sultan Qaboos disposed his father and funneled the Sultanate’s treasuries and workforce into national development (Jones and Ridout 2015). Protected areas and cultural heritage sites were also established beginning at this time. Some of these are administered directly under a royalty land stewardship structure (the Diwan of the Royal Court) and others administered by what is now the Nature Conservation Authority of the Ministry of Environment and Climate Affairs (MECA). Though cultural sites are maintained for both preservation and tourism with the Ministry of Heritage and Culture and concessionaire contracts, almost all of the 20 natural resource protected areas are maintained solely for preservation and scientific studies and without associated contracts for development or programming (Mershen 2007; MECA 2022).

At this economic-based inflection point in time, Oman is considering how to thoughtfully leverage some of these protected areas for increased NBT to the country. And, they have good reason to expect that nature-based tourists would come for these outstanding resources and experiences. Oman’s current tourism slogan is “Beauty has an address – Oman”, and rightly so. The country is brimming with unique environments and relatively constrained large-scale development as compared with its neighbors in the Gulf of Arabia. For example, its waters and beaches support many of the world’s migratory sea turtle species and tourists can observe – with a guide and under regulations – egg laying or hatching from these species throughout the year. Wildlife is also found throughout the country’s beaches, deserts, mountains, and wadi (river canyons with seasonal/year-round water), including ibex, falcons, gazelles, oryx, and the last known populations of the Arabian leopard (Panthera pardus nimr). Flora include acacia, frankincense, oleander, and date palms. In all of these environments, humans have had a pronounced presence historically and/or currently, and cultural resources from the Bronze Age (2300 BCE) onwards are common sights. Perhaps most famously, the Omani system of falaj (singular) / aflaj (plural) or above ground irrigation channels and community-based allocations of water in diversion systems to distribute water from mountain springs and snowpack to lower land farms, is protected and promoted under UNESCO World Heritage Site designation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Examples of falaj irrigation channels in a wadi near the source of the water (left) and within a cultivated area of date palms, fodder grasses, and citrus trees (right).

Also of note is the attraction of tourists themselves to Oman. With a rich seafaring and trading history, Oman has a longstanding tradition of welcoming different peoples and viewpoints, showcasing its hospitality, and encouraging cultural exchange (Jones and Ridout 2015; Subramoniam et al. 2010). In the past 10 years, tourist visitation to Oman has doubled, reaching approximately 230,000 visitors in 2019 (National Centre for Statistics and Information 2019). In that year, the Omani tourism sector generated more than 80 million Omani rial in revenues (approximately US$200 million) on tourism experiences, accounting for nearly 5% of Oman’s gross domestic product (Al-Hashim 2015; Cetin & Al-Alawi 2018; National Centre for Statistics and Information 2019). While this level of tourism represents a real contribution to the Omani economy, the Omani tourism sector remains at or below regional averages for economic size and productivity, indicating even greater potential to grow and develop the tourism sector in the future (Cetin & Al-Alawi 2018). A critical enabler of the Omani tourism economy is its regional leadership in safety and security for tourists in the country, for which it is ranked first among Middle Eastern and North African countries (Cetin & Al-Alawi 2018; World Economic Forum 2019). Oman has taken a role of diplomatic neutrality amongst its more politically volatile neighbors (e.g., Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Iran) and thus is viewed as a generally more safe and stable atmosphere for tourism in the region (Stephenson and Al-Hamarneh 2017).

Tourists mainly come from the other countries within the Gulf region, especially to enjoy Oman’s comparatively more temperate conditions and diverse scenery, and from countries across the Indian subcontinent (Al-Hashim 2015; Tanfeedh 2017). Smaller but growing tourism markets include Europe, Russia, and China. Tourists from other areas are fewer, though there is a niche market for tourism from U.S. military personnel and their families stationed in Bahrain and the greater region (Stephenson and Al-Hamarneh 2017).

Complexity of Development

Despite these attractive resources and current tourists, NBT combining the two has not been an explicit focus until recently. With resources under the purview of MECA and tourism under the Ministry of Tourism (MOT), the two have diverged in goals and policy in this separation. In the current state of economic diversification and greater emphasis on promoting NBT, a critical issue has arisen:

How to work with multiple ministries and multiple goals to provide quality NBT experiences in sensitive, often wildland environments, while maintaining the quality of these environments themselves?

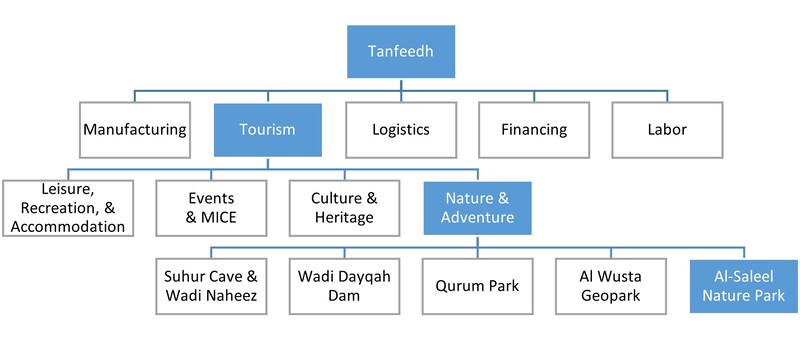

This question transcends contexts, but the Omani version of it has trended toward the tension of “opening up” protected areas for NBT and attracting private investment to develop tourism infrastructure and programming in and near these places. As part of a national economic diversification strategy (Tanfeedh 2017), five protected areas were identified for NBT development (Figure 3). These “pilot” protected areas for nature and adventure tourism would showcase the desert, marine, cave, wadi, wetland, and montane environs of the country, provide new destinations on travel itineraries for tourists’ typically short stays in Oman, and capture a newer market of thrill-seekers across the Gulf. The pilots are a cave system at the base of the mountains (Suhur Cave and Wadi Naheez), an immense dam and corresponding water resources (Wadi Dayqah Dam), an protected wetland in urban Muscat (Qurum Park), a rock and fossil interest site in central Oman (Al Wusta Geopark), and an acacia desert shrubland (Al-Saleel Nature Park).

Figure 3. Tanfeedh’s hierarchical organization of sectors, initiatives, and projects (top to bottom), as related to Al-Saleel Nature Park. MICE = Meetings, Incentives, Conferences, and Exhibits

Questions have arisen in particular about Al-Saleel Nature Park, which is the pilot area with the current most stringent MECA protections. It is part of the Omani Nature Reserves system, which is akin to an IUCN Category Ia strict nature reserve managed mainly for science and is correspondingly wild in nature (Dudley et al. 2013; MECA 2022). Al-Saleel is located in eastern Oman, at the western foot of the southern end of the Eastern Hajar Mountains, covering 220 square kilometers (85 square miles). It is under the jurisdiction of MECA. The park is designated to protect habitat for Arabian gazelles (Gazella arabica) and foster the growth and health of that population (Figure 4). It also contains the largest acacia woodlands in Oman and encompasses an important ecological transition zone between the northern and southern Sharqiyah deserts. The three main areas of the park are alluvial plains with acacia, mountains and wadis, and sparsely vegetated higher elevation hills and outcrops (Figure 5). In addition to its environmental values, the reserve contains Bronze Age archaeological sites (e.g., beehive-shaped tomb structures) and seabed fossils of ancient marine life (MECA 2017).

The park was only recently opened for visitation and primarily serves school and other organized groups on trips pre-planned with the MECA regional and national offices. Primary facilities include an administrative office with a small collection and an exhibition of natural artifacts from the park, informal camping locations, a limited network of unimproved roads and driving routes, a gazelle breeding and care facility, and a native plant nursery. Administration of the park is headed by a park director and a cadre of rangers who patrol the reserve to monitor conditions and deter illegal activities including establishing goat grazing pens and poaching of protected wildlife (MECA 2017).

Figure 5. A view of the expanse of the alluvial plains with acacia trees at Al-Saleel Nature Park (top), viewed from the rocky hills and outcrops between the plain and the northern mountains (bottom). The unimproved road visible is the only route maintained in the park.

One additional reserve – Ras al Hadd Turtle Reserve – is already a tourism destination and has had to manage and adapt the balance between visitation and use (Choudri et al. 2016a). It is thus held as the model for how NBT can occur in environmentally sensitive yet economically contributory ways. In this particular case, visitors typically spend only a few hours at the reserve at dawn for the first glimpse of sunrise in Arabia and to see hatchlings surging toward the surf or at dusk/night to see turtles depositing their eggs into sandy nests. Limitations on visitation; guided experiences; a visitor center to constrain impacts, convey policies, and educate visitors; and a new ecolodge are all management strategies that MECA has implemented with a concessionaire and MOT guidance (Figure 6). However, there are concerns that major surges in visitation around Eid al-Fitr (the festivities marking the conclusion of Islam’s most holy month, Ramadan) and other holidays violate the limits set by MECA and favor tourism over protection. Management plans for the turtle reserve are based on the resource itself. Because tourism and its impacts was not an original consideration in the reserve, but rather one in response to unmanaged conditions 10-15 years ago, tourism is still seen as at-odds with the fundamental purpose of the reserve. As the lone example of a MECA – MOT collaboration, the challenges and successes at Ras al Hadd have set the tone for discussions about considering NBT in other reserves.

Figure 6. Ras Al Hadd Nature Reserve experiences clockwise from top left: visitor center, ecolodges, guided night hike, and beaches, with a sea turtle depositing her eggs, illuminated by a less disturbing red light (center).

The inclusion of Al-Saleel as an additional nature reserve for NBT in Tanfeedh and the assumption of Ras al Hadd as a model for such tourism development has demonstrated reoccurring obstacles. Al-Saleel began working on NBT development from the park-level at the same time as Tanfeedh was focusing on heritage from the national level. These efforts developed in parallel. MECA tourism development actions that predated or parallel Tanfeedh tourism sector implementation include expert-exchange with the US Department of Interior for technical park planning and management support and drafting of management plans that incorporate tourism as a critical area of emphasis (MECA 2017). The park’s own tourism management and development efforts motivated and have supported inclusion of the Al-Saleel tourism project within Tanfeedh.

To date, at least three separate efforts have been made by MOT to initiate tourism development at Al-Saleel, none of which has advanced beyond the initial speculative stages. This pattern of consistent interest that falls short of implementation is an important contextual framing for the discussions about wildland NBT in Omani reserves. Al-Saleel has repeatedly been recognized as a priority for tourism development among Oman’s protected areas and natural heritage resources. Government and private sector resources have on several occasions been committed to developing plans, yet none of these plans has been implemented. This suggests that greater system-level barriers and unreconciled points of friction may be preventing development of Al-Saleel. For example, these larger barriers include:

- Ministry-to-ministry issues such as initial and genuine interests in collaboration encountering the realities of already-overcommitted staff and processes particular to each ministry, and

- Ministry-to-provider issues such as effectively marketing the financial attractiveness of nature reserves’ potentially seasonal tourism to entrepreneurs and providing clear pathways for small and medium enterprises (ideally locals and Omanis) to engage in small-scale NBT ventures.

Moving Forward

The presence of such barriers and points of friction is particularly troubling within the protected area context of the park. Al-Saleel was designated as a national nature park to protect and preserve valuable, unique, and sensitive resources (e.g., gazelles, acacia) and experiences (e.g., learning about regional lifeways, connecting with Omani nature). To be successful and sustainable, NBT development in Al-Saleel must be well-coordinated and sensitive to the environmental and social constraints of the park and its surroundings. As a relatively intact ecosystem with traditional cultural uses (e.g., camel and goat grazing, honey collection), developing a lodge or highly structured campground on the park’s border and amenities in the park such as a 10k trekking/jeep safari trail (i.e., improving the road pictured in Figure 5) would impact the integrity of the resource and the villages surrounding it (MECA 2017). The national significance of the area, as expressed though its selection as a Tanfeedh project, stands at odds with the start-and-stop nature of development efforts and raises important questions about the relevance of and proper direction for tourism development in and around Al-Saleel.

The circumstances of Al-Saleel, both its potential for sustainable tourism development and the challenges that have arisen while trying to realize this potential, are not unique to the park. They are typical of many Omani natural and cultural heritage tourism destinations and indeed of parks worldwide (Manning 2011; McCool 2016; Spiess et al. 2017). Virtually all parks and protected areas face tensions between development and protection, public and private interests, national and local values, and recreation and conservation uses. Therefore, analyzing the history, context, and alternative futures for tourism development at Al-Saleel provides a case study that will be useful for successfully and sustainably developing other Omani natural and cultural heritage resources for tourism.

Even with these similarities, Oman is unique in many respects and poised to be a leader among its petroleum-producing peers in attention to environmental concerns (Choudri et al. 2016b). As the country established its wealth and infrastructure, it also established substantial areas of cultural and environmental protection. The country participates in UNESCO designations and has demonstrated commitment to true nature reserves (IUCN Category 1a; Clarke et al. 1986). More broadly than just protected areas, it has capitalized on its appeal as a nature oasis among its relatively more arid neighbors. The question now turns to how these earlier advancements will remain and/or adapt as NBT becomes a more emphasized sector for attracting new revenue (Mershen 2007). As the existing nature reserves are preservation-focused, reconciling the fundamental purpose of these places with the idea of tourism development is challenging – as seen in Ras al Hadd and Al-Saleel – and will remain a challenge as MOT and MECA bring NBT collaboration toward action. Optimism remains though that among the dramatic beauty of such places the enduring commitment to protected areas and relatively more recent recognition of their economic appeal can help forge solutions. Establishing additional types of protected areas with appropriate tourism development considered at the onset, and encouraging small seasonal NBT providers.

“Optimism remains though that among the dramatic beauty of such places the enduring commitment to protected areas and relatively more recent recognition of their economic appeal can help forge solutions.”

About the Author

ELIZABETH (BESS) PERRY is an assistant professor of protected areas and natural resources recreation Management, in the Department of Community Sustainability at Michigan State University. Dr. Perry is a social scientist who researches and teaches about parks, outdoor recreation, and related tourism. Her work addresses vital issues for managers, visitors, and communities, such as relevance, sustainability, collaboration, inclusion, and scales of impact. She was the 2018 Sultan Qaboos Cultural Center Research Fellow to the Sultanate of Oman, where she focused on issues of sustainable nature-based tourism development in Omani protected areas.

References

Al-Hashim, A. 2015. Embracing sustainable tourism in Oman: Case study of Mirbat settlement. International Journal of Cultural and Digital Tourism 2(2): 8-16.

Buerkert, A., E. Luedeling, U. Dickhoefer, K. Lohrer, B. Mershen, W. Schaeper, M. Nagieb, & E. Schlecht. 2010. Prospects of mountain ecotourism in Oman: The example of As Sawjarah on Al Jabal al Akhdar. Journal of Ecotourism 9(2): 104-116.

Cetin, I., & A. N. Al-Alawi. 2018. Economic diversity and contribution of tourism to Oman economy. International Journal of Tourism, Economics and Business Sciences (IJTEBS) E-ISSN: 2602-4411 2(2): 444-449. https://doi.org/ 10.9790/487X-1906040912

Choudri, B. S., M. Baawain, and A. Mushtaque. 2016a. An overview of coastal and marine resources and their management in Sultanate of Oman. Journal of Environmental Management & Tourism 7.1(13): 21-26.

Choudri, B. S., M. Baawain, A. Al-Sidairi, H. Al-Nadabi, and K. Al-Zeidi. 2016b. Perception, knowledge, and attitude towards environmental issues and management among residents of Al-Suwaiq Wilayat, Sultanate of Oman. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 23(5).

Clarke, J. E., F. M. S. Al Lamki, V.C. Anderlini, & C. Sheppard. 1986. Sultanate of Oman: Proposals for a system of nature conservation areas. International Union for Conservation of Nature. IUCN-Rep-1986-Clar-001. World Conservation Centre: Gland, Switzerland.

Dudley, N., P. Shadie, & S. Stolton. 2013. Guidelines for applying protected area management categories including IUCN WCPA best practice guidance on recognising protected areas and assigning management categories and governance types. IUCN Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series, 21. https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/PAG-021.pdf

Jones, J., & N. Ridout. 2015. A history of modern Oman. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Manning, R. E. 2011. Studies in outdoor recreation. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press.

McCool, S. F. 2016. Tourism in protected areas: Frameworks for working through the challenges in an era of change, complexity, and uncertainty. In Reframing sustainable tourism. Springer: Netherlands.

Mershen, B. 2007) Development of community-based tourism in Oman: Challenges and opportunities. p. 188-214 in Daher, R. F. (ed.) Tourism in the Middle East: Continuity, change, and transformation. Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK.

Ministry of Environment and Climate Affairs. 2017. Nature based tourism plan, Al Saleel Nature Park. Muscat: Sultanate of Oman Ministry of Environment and Climate Affairs, Nature Conservation Section.

Ministry of Environment and Climate Affairs. 2022. Authority mandates: Natural reserves. Available at: https://www.ea.gov.om/en/the-authority/authority-mandates/nature-conservation/natural-reserves/?csrt=4929670947643238547. Accessed 8 February 2022.

National Centre for Statistics and Information. 2019. Annual number of visitors– Expatriate/non-Omani. Muscat: Sultanate of Oman. (in Arabic) https://www.ncsi.gov.om/Pages/AllIndicators.aspx

National Program for Enhancing Economic Diversification (Tanfeedh). 2017. Tanfeedh handbook. Sultanate of Oman National Program for Enhancing Economic Diversification: Muscat.

Spiess, A., F. Al-Mubarak, & A. S. Weber. (Eds.). 2017. Tourism development in the GCC states: Reconciling economic growth, conservation, and sustainable development. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Stephenson, M. L., & A. Al-Hamarneh. (Eds.). 2017. International tourism development and the Gulf Cooperation Council states: Challenges and opportunities. Contemporary Geography of Leisure, Tourism, and Mobility series. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Subramoniam, S., N. Al-Essai, S. Ali, A. Al-Marashadi, and A. Al-Kindi. 2010. SWOT analysis on Oman tourism: A case study. Journal of Economic Development, Management, I.T., Finance, and Marketing 2(2): 1-22.

Tanfeedh/National Program for Enhancing Economic Diversification. 2017. Tanfeedh handbook. Muscat: Sultanate of Oman National Program for Enhancing Economic Diversification.

World Economic Forum. 2019. The travel and tourism competitiveness report 2019: Travel and tourism at a tipping point. Geneva: Author. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TTCR_2019.pdf

Read Next

What is visitor use management? Identifying functional and normative postulates of an interdisciplinary field of study

The axioms of Visitor Use Management can guide us towards a future that enriches the lives of the public while preserving our cherished resources for generations to come.

Are We in Need of “Triage” for Wilderness?

As part of a larger management strategy, “triage” actions can work with long term decision-making to provide wilderness managers with the best practices necessary for wilderness stewardship.

Nature in the Anthropocene: What it no longer is, Will never again be, and What it can become

Nature changes in response to changing conditions, and so must our conception of it.