INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

April 2015 | Volume 21, Number 1

BY ELENA NIKOLAEVA, ANNA ZAVADSKAYA, VARVARA SAZHINA, and ALAN WATSON

PEER REVIEWED

Abstract: A common justification for developing ecotourism opportunities within protected areas is that it helps to secure long-term conservation of wildlife and habitats and contributes to local socioeconomic development. Since establishment of Russia’s first protected area in 1916, Russia has developed the world’s largest system of strictly protected nature reserves (zapovedniks) and sanctuaries (zakazniks). Most tourism had been prevented in these areas until federal law changed to permit educational tourism. Russian nature-reserve administrators hope it will lead to greater public involvement and public and financial support. Because little is known about the attitudes of local community residents and visitors in Russia toward protected areas, conservation efforts, and tourism practices, the present study describes stakeholders’ attitudes and knowledge in the South-Kamchatka Sanctuary, in Far East Russia. A positive evaluation of the purposes of the protected area, both by visitors and community members, was found. However, some negative attitudes and experiences were identified as well, caused mostly by the lack of effective interaction between protected area managers and stakeholders.

One of the main arguments for tourism development in or around protected areas (PAs) is that it helps to secure long-term conservation of nature (Goodwin et al. 1997; Newsome et al. 2004). If carefully designed, managed, and delivered, ecotourism can increase conservation knowledge, change attitudes and behavior of tourists and residents, contribute to resource conservation, provide opportunities for economic development of the region, and enhance the quality of life of local residents (Fiallo and Jacobsona 1995; Goodwin et al. 1997; Saarinen 1998; Gray et al. 2003; Andereck and McGehee 2008; Ballantyne et al. 2009). Collaboration with local communities, as well as implementation of appropriate planning and management strategies aimed at reducing negative impacts, is essential to the development of a sustainable ecotourism industry (Shultis and Way 2006; Ballantyne et al. 2008).

Russia has a long and rich history of nature conservation, with its first federal protected area (Barguzinsky Zapovednik) established in 1916. However, the system of PAs has not been responsive to society’s changing needs, and managers did not recognize the importance of people’s support in the conservation process. From the beginning, the Russian zapovedniks (strict nature reserves that provide the highest level of protection – Category 1a, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature), emphasized preservation of ecosystems primarily for ecological research. Management strategies excluded any type of economic activities, entailed strict rules regarding access (including recreation) and natural resource use, and kept potential tourists as well as local residents from being involved (Weiner 1999; Colewell et al. 1997; Ostergren and Hollenhorst 1999). Such isolation from the public often brought about negative attitudes toward PAs and conservation generally. This approach dominated management goals up to the early 1980s, when the first national parks appeared in Russia. Conservation policy was broadened at that time to include environmental education, and later, ecotourism (especially after 2011 when federal law changed to permit and encourage educational tourism in protected areas (Federal law #33- FZ 1995).

Today among the main priorities of zapovedniks, national parks, and zakazniks (federal sanctuaries) in Russia are environmental education, cooperation with local communities, and development of ecotourism. These policy changes are intended to serve as a deterrent to poaching and other forms of illegal land use. Managers have to introduce new tools, learn to cooperate with stakeholders, and understand societal values to achieve sustainable environmental, social, and economic outcomes.

Ecotourism is of growing interest as a way to achieve environmental sustainability and economic development (Kruger 2005; Aylward et al. 1996). As countries often move from developing to developed, attitudes change in regard to how people value nature and how they perceive conservation (Watson et al. 2009a, 2009b). Knowledge about stakeholders and their attitudes has been described by Watson et al. (2009b) as one of the pillars of sustainable tourism development.

Despite the recognized importance of collaboration with various stakeholders in ecotourism development (Fiallo and Jacobsona 1995; Ceballos-Lascurein 1996; Eagles at al. 2002; Andereck and McGehee 2008; McCool 2009), little social science research in this field has been done in Russia. One of the first studies in Russia was focused on better understanding visitation and economic aspects of sustainable tourism development in Kamchatka (Watson et al. 2009b). It provided knowledge o: (1) characteristics of tourists and their current experiences in Kamchatka PAs; (2) existing and potential financial influences on tourism; (3) attitudes toward protection options in Kamchatka PAs; and (4) proportion of tourism expenditures in service-related industries and economic benefits from tourism to PAs and local communities. Although visitor-spending profiles could be developed for foreign and domestic tourists, it was difficult to determine how these visits contribute to local economies due to lack of local and regional economic structure data. In general, such tourism in Kamchatka lacks educational contributions and does not influence environmental awareness of visitors. The study facilitated conservation planning in Kamchatka and provided a basis for future and more specific projects, including the current investigation.

The aim of this research was to explore residents’ and visitors’ attitudes and awareness of conservation and tourism management in the South Kamchatka Sanctuary in Far East Russia. Researchers also explored conflicts in the relationships among local communities, nature conservation, and tourism. This knowledge is important on a broader scale not only for this specific site but also for the system of Russian protected areas to facilitate more effective stewardship, preservation of nature, and sustainable development.

South-Kamchatka Sanctuary

Kamchatka scenery and wildlife attracts tourists from all over the world – about 70% of the most popular tourist attractions of the region are located within protected areas (Zavadskaya and Yablokov 2013). The values of tourism resources of the peninsula are inextricably linked to their naturalness (Zavadskaya and Sazhina 2012). South-Kamchatka Sanctuary (SKS), chosen for this casestudy, is located in the south part of Kamchatka Peninsula (Figure 1) and occupies 322,000 hectares (796,000 acres), including 225,000 hectares (556,000 a) of land and a 3-mile offshore zone. It was established in 1983, mainly for the conservation of habitats and populations of sea otters, Steller’s sea eagles, northern falcons, black-capped marmots, bighorn snow sheep, brown bears, migration routes of birds, and salmon-spawning habitats at Kuril Lake (Figures 2, 3). The sanctuary is managed by Kronotsky State Natural Biosphere Reserve and equates to IUCN management category IV (although its protected regime is very close to that of a zapovednik, category 1a). Due to rich wildlife diversity, opportunities to see bears in close proximity, and picturesque scenery, the area is now used for ecotourism. However, access to the SKS is limited and strictly regulated. Approximately 1,500 tourists each year are able to visit the PA, and this number will likely increase because of the destination’s promotion by protected area managers and travel agents.

Three rural communities (Ozernaya, Zaporozye, and Pauzhetka) are located just outside the northern boundary of the sanctuary, with approximately 2,500 residents. SKS is a good example of a remote and isolated site (like many PAs in Russia) where people’s lives and local economies are built on the utilization of natural resources and strongly depend on resource sustainability. However, some of residents’ activities – illegal fishing and hunting – as well as unmanaged tourism have great potential to degrade SKS’s environmental values. Ecotourism development in such an area could be an important addition to a limited range of economic opportunities, also deterring poaching and other forms of illegal land use through raising the level of environmental awareness of the residents.

Figure 2 – Kuril Lake is the largest spawning reservoir for red salmon in Eurasia. Several million individuals come to the lake every year, giving food to animals and jobs for residents of the adjacent villages. Photo by Elena Nikolaeva.

Figure 3 – The population of brown bears in SKS is one of the largest in the world (about 1,000 individuals). Up to 200 bears can be found on the shores of Kuril Lake during the spawning season. Kamchatka is the only bear region in the world where all three types of fattening food are available for them: berries, pine nuts, and salmon. Photo by Elena Nikolaeva.

Methods

In July and August 2012 a public opinion survey was conducted among local residents of the three villages adjacent to the sanctuary and with a sample of visitors to SKS. Fifty-three interviews were conducted (27 local people, 26 visitors). Three researchers (authors of this article with proficiency in both English and Russian) conducted the interviews.

The survey of local communities utilized a snowball sampling method, most appropriate for studying unknown or rare populations (Coleman 1958; Goodman 1961; Spreen 1992). The researchers first interviewed random people they encountered in the communities; they then chose other respondents based on the recommendations received (residents named people active in tourism, businesspersons who were involved in the fishing industry and forestry, teachers working with schoolchildren, etc.). In the visitor survey several random members from each organized tourist group that visited the SKS during the research period were approached and invited to participate in the interview. The interviews lasted 15 to 40 minutes. The response rate was 91%.

Surveys were analyzed (Corbin and Strauss 2008) to describe attitudes among the respondent groups in the following thematic areas: (1) perception of South-Kamchatka Sanctuary; (2) awareness of, and interest and engagement in conservation issues; (3) attitudes toward recreational and tourism activities in SKS; (4) economic contribution of tourism to local communities; and (5) management of the sanctuary. While answers were recorded in the language of the respondent, for this article all results are translated into English by the authors.

Results: Perception of South-Kamchatka Sanctuary

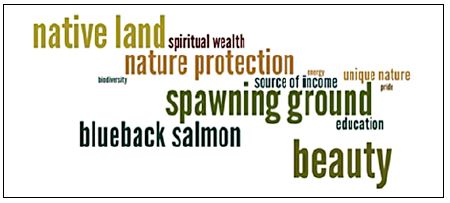

Community members – A large set of questions was devoted to revealing the values of SKS. Figure 4 demonstrates the themes that emerged during the interviews with community members: the largest words are the strongest themes. Many respondents emphasized aesthetic, spiritual, and educational values of the SKS:

For me it’s mostly beauty. It’s sacred. The only place in the world like this, which we should definitely conserve. Kuril Lake is like “to see Paris and die.” A place of worship.

Results also indicated a very high dependence of the locals on the sanctuary. Being mostly employed in the fishing industry, residents understood the great importance of SKS as a salmon spawning ground and highly valued the conservation role of the PA:

The village will be alive as long as there will be fish in Kuril Lake and Ozernaya River.

Figure 4 – Value of SKS for local communities (answers to the open ended question: “What is the value of SKS for you personally?”)

In general, of the four possible orientations toward protected areas (Saarinen 1998) (utilism, humanism, mysticism, and biocentrism), the attitudes of local residents toward SKS can be characterized as humanistic. The majority of community members value the PA and natural environment for promoting human development in a variety of ways: both as a source of raw materials (mainly biological resources) and also as a means to attaining ethical, aesthetic, and mental equilibrium. Such attitudes toward a protected area create good prerequisites for developing effective collaboration with local communities and implementing community-based recreation management practices.

Visitors – The survey of SKS visitors and travel agents demonstrated the value as a tourist destination. Almost every respondent emphasized the conservation role of SKS and highly valued its natural features.

“It’s a place where you can be out in nature untouched by man, a place that is not destroyed by man, and which is protected. Here it’s perfect.”

“I live in town where there is a lot of stress. And here it’s silent, and we witness a mystery of nature. And the relationships between people are closer than in towns.”

The main role is to sustain ecosystems and nature cycle intact. Keep it the way it is.

Conservation Issues

Community members – Participants were asked to indicate their awareness of, interest, and level of engagement in conservation issues. The results indicated very high support for conservation in general, with 95.2% of respondents agreeing that “it is good that South-Kamchatka Sanctuary (and Kuril Lake in particular) is protected by the government.” That was a common theme for most of the respondents: nature conservation has always been perceived as a government responsibility – there are very limited private initiatives in this regard – and despite different attitudes, most people believe that it is good that authorities are in charge of protection. Almost all local community members agree that it is necessary to protect the sanctuary, and it is good that the government does it.

The level of local residents’ environmental education and current engagement were very low. Respondents were aware of such conservation activities as ecological campaigns, public land/water clean-ups, collecting litter left by other visitors in picnic areas, and so forth, but most respondents were not familiar with specific SKS goals and how exactly they could make a difference in nature conservation.

Most respondents could easily provide interviewers with a list of the main threats to SKS and the natural environment (see Table 1). However, when asked about solutions to these problems, most were unable to name even one possible conservation action needed for addressing the issue.

In spite of the fact that local residents were quite concerned about conservation issues, about one-third of them were not aware of SKS protection status, its boundaries, and its special regulations. The results, therefore, suggest that there is great potential for building effective collaboration with local communities who share interest in conservation issues, but the current level of interaction between SKS and residents is very low.

Visitors – One of the main concerns of SKS visitors was possible overcrowding: the sanctuary attracts increasing numbers of tourists each year, which may lead to crowding issues, littering, and possible changes in bears’ behavior. As a consequence, the unique wilderness character of the area may be affected. Industrial development and poaching were also listed as possible threats.

Attitude Toward Tourism and Recreation Activities in PA

Community members – Overall, local residents expressed support and positive attitudes toward tourism development in SKS and the region. Most would be happy to see more tourists (85.7%). The majority of respondents (90.5%) also agreed that “tourists come here because of South-Kamchatka Sanctuary and Kuril Lake.”

Visitors – Respondents were placed into two different groups, foreign and domestic, and responses contrasted. While almost all foreign visitors mentioned “seeing bears” as the primary purpose of their trip (66.7%), the responses of domestic travelers were as follows: “to see bears and fish” (36.6%), “to visit Kuril Lake” (15.7%), and “to enjoy beauty and wildlife in general” (42.1%). At the same time, 21.1% of the domestic respondents were unable to provide a reason for choosing SKS as their destination: it was either “offered by a travel agent,” or “suggested by a friend”; this category of respondents did not have clear expectations about their trip.

The majority of Russian tourists (57.9%) had no idea about ideology of ecotourism or its definition and principles. Among the answers concerning the definition of an “ecotour” were the following:

“In my opinion an ecological tour is when people go to the village and eat eco-friendly products. Our tour was a bit different, it was a slow hike.”

As I understand it, it’s when a group of tourists/volunteers are brought somewhere in the field and they collect garbage there.

Foreign tourists that visited SKS during the research period (mainly from Austria, Germany, France, Switzerland, and the United States) were much more aware of the ideology of ecological tourism and were more concerned about the details – the sewage system, which laundry and dishwashing products are used, how the waste is disposed, and so forth. For citizens of more developed countries where healthy lifestyle and environmental quality are promoted, these details are important.

My tour is fifty-fifty. We tried to live the most ecological way as it is possible for this place. But if we compare with my standards in Switzerland, here people don’t think about ecological things – like laundry products, products for dishwashing, soap. In my country, I buy only ecologically friendly products, but they are of course more expensive. Here, because the region is poorer, people think less about the ecology.

The results indicate a great variability in attitudes and perceptions toward tourism between domestic and foreign visitors, which can likely be attributed to different levels of ecological ethics and cultural history. Another important finding was that more than one-quarter (26.9%) of visitors to SKS (42.3% of whom were Russians) were not aware of the conservation status of the visited area.

We knew it would be interesting here, but we did not know that it’s a protected area.

Our travel agent suggested this trip. We wanted something interesting, where there would be bears. I didn’t know that it’s a sanctuary.

Economic Contributions of Tourism for Local Communities

Community members were asked to identify the existing benefits from tourism. Almost everyone supporting tourism clearly linked it with potential benefits for the region in general or his/her family in particular. Among possible benefits identified were the development of community infrastructure, new job opportunities, and income from selling souvenirs, crafts, and food products. However, the majority of respondents did not believe they receive any direct benefits from tourism.

Management of the Sanctuary

Community members – Most community members indicated positive support for the sanctuary, although some negative attitudes and experiences were identified. The most frequently mentioned negative attitudes were restrictions imposed on access to the area (47.6%), controlled movement within SKS boundaries (33.3%) and resource use (ban on gathering berries and mushrooms [38.1%], prohibition of fishing [19%]).

Maybe it’s not necessary to protect this area so much from local people? If I come there and pick several mushrooms or berries is it really that bad?

Recently we could just get together and go there for a picnic. Now we need to go somewhere and take a permit. We can’t eat berries and collect wild leek.

The prices at Kuril Lake are too high, so locals simply can’t go. Why should I pay to come there? Why did they close it?

Interviews with the PA managers found that most of the restrictions noted do not apply to locals, who have certain privileges that they are not aware of – for example, free access to SKS territory (with permission and provided that they follow the rules), specially designated zones within the PA for picnicking and collecting mushrooms and berries, and so forth. Therefore, the problem of lack of regular dialogue and cooperation among PA administration, local authorities, and residents was revealed, which caused conflicts and prevented establishment of effective partnerships with stakeholders.

Visitors – SKS visitors were quite positive about management of the sanctuary, and recreation management in particular. The majority of respondents (60%) evaluated the existing infrastructure positively, and 40% specifically emphasized the excellent work of SKS staff.

Respondents were verbally asked to rate their satisfaction on a 10-point satisfaction scale. The majority of respondents (76%) were totally satisfied, giving the maximum rating (10 points). Although most visitors were positive about their experience, 36.4% gave comments somehow related to “touristization” of the area that is promoted to be wilderness – they were concerned about excessive construction, nonnatural noise, a large number of helicopters, and they recommended to keep this place natural.

Discussion and Conclusion

Tourism in protected areas is promoted as an effective conservation tool based on a number of assumptions. From a conservation perspective, it is expected to be environmentally sustainable and provide tangible benefits to protected areas in the form of revenues earmarked for conservation and management (Walpole and Goodwin 2001). From a community perspective, it is expected to provide equitable socioeconomic benefits that in the long run will enhance local support for conservation (Goodwin 1996). From a visitor’s perspective, it should contribute to environmental education, encourage contribution to conservation, and meet expectations.

Although attractiveness of the Kamchatka region and its protected areas for ecotourism is apparent, there are many remaining questions regarding tourism, its sustainability, and its connection to local communities. Positive local attitudes toward conservation and tourism are the first building blocks toward achieving conservation in nature-based tourism destinations (Fiallo and Jacobsona 1995; Walpole and Goodwin 2001; Mbaiwa and Stronza 2011). This study indicated relatively strong attachment to the territory by locals and a very high level of support toward conservation ideas in general and SKS in particular. At the same time, however, SKS administration was sometimes criticized by residents for current management, and communication with the community was judged to be unsatisfactory.

Although today the life of local residents is not impacted much by tourism, there are some potential local tourism benefits, and communities clearly recognize the link between these benefits and the sanctuary (mainly Kuril Lake). Lack of cooperation with PA administration, as well as low current economic contributions of the protected area to adjacent villages contribute to unfavorable views about current general and visitor management. Developing tourist programs that include visits to the adjacent villages would generate significantly higher revenue for local residents and thus would improve social sustainability of tourism development; it should also increase the level of residents’ support for conservation ideas as those programs would be developed in cooperation with the protected area.

There is believed to be high value of the territory for further ecotourism development, but there is also a huge gap between the current tourist experience and the ideology of ecotourism. Current tourist programs provided by travel agents, in cooperation with SKS, mainly aim to demonstrate unique

natural features of the place, but they fail in the issues of interpreting nature and raising the level of visitors’ conservation support and environmental awareness. The researchers listened to several excursions at the SKS conducted by travel agents, and almost none of them emphasized the role of the protected area in conservation of ecosystems and sustainable development of the area. The majority of tourists (mainly from Russia and Ukraine in this study) are not familiar with the principles of ecotourism and often have no idea of the visited area’s conservation status. In order to encourage educational and responsible tourism in the area (as suggested by federal law), this issue should be addressed – mainly by training travel agents and making tours more conservation focused.

The project team has developed several practical recommendations. First, it is clear that benefits from tourism in SKS are unequally distributed, and local communities get almost no profits (profits go to travel agents and SKS). This is recognized by local people and may influence their attitudes toward the protected area and tourism development. Ensuring a fair and equitable distribution of benefits is critical for effective management of SKS, sustainable development around the PA, and gaining support from stakeholders. This might be achieved by avoiding “enclave” practices (Freitag 1994), in which both trip organizers and tourists are nonlocals and local access to the tourism market is limited, and encouraging greater entry of local communities into tourism activities. In this case there would be more opportunities for local economic development, diversion of tourist dollars from the travel agencies to residents, and greater conservation support.

Second, ecotourist destinations often stand out as places that allow a visitor to come face-to-face with nature and gain from the experience of it (Saarinen 1998). Increases in accommodation capacity and general “touristization” that often occur in such areas will inevitably change the meanings that tourists attach to natural destinations and influence their basic motives for visiting. So, appropriate plans for tourism development with either diversification of tourism programs and offering various recreation opportunities, or ensuring meeting the needs of “true” ecotourists should be developed and implemented.

Third, although this study did not reveal many negative attitudes, it was undertaken at an early stage in tourism development. Patterns of attitude, both of tourism and of conservation, may change as tourism develops (Doxey 1975). It is therefore important to ensure regular and longterm monitoring of the performance of tourism management that will focus on ecological, economic, and social impacts. More detailed studies aimed at revealing relationships between people and protected areas conducted over time might provide greater insight into the mechanisms that shape local attitudes toward conservation and development in this region and elsewhere (Figure 5).

Figure 5 – Not all visitors agree with current management practices and the “touristization” of SKS. Many fear the problem of unexpected overdevelopment of the area with tourist infrastructure, overcrowding, and travel impacts. Photo by Anna Zavadskaya.

Fourth, successful protection of wilderness areas should not only be based on the management of ecosystems but also include techniques and approaches that provide respect to local communities and lead to a sustainable social system (Saarinen 1998). Ecotourism management practices that enlist local residents and tourists as conservation partners, clearly communicate the reasons behind any constraints imposed, and present a consistent message regarding involvement in tourism and conservation activities are very important. These are the practices that are likely to be most successful in meeting the needs of protected area managers, local communities, tourists, and other stakeholders and, therefore, should be implemented in this and other nature-based tourist destinations.

Kamchatka is a unique place, which is attracting increasing numbers of visitors from all over the world. The importance of protecting Kamchatka’s wild and undisturbed areas seems beyond question among visitors and local communities. However, societal changes will likely affect people’s attitudes and values toward conservation ideas and management practices (Watson et al. 2009b). Social research is an important tool in tracking these changes, reveals existing and potential conflicts and opportunities, and enhances both environmental and economic sustainability in the long run.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their deep appreciation to the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute for funding and facilitating this research, BLM’s Alaska State Office for financial sponsorship, Kronotsky State Nature Biosphere Reserve for the opportunity to conduct the research and for providing accommodation and transport for the team, and all interview participants for their patience and input.

References

- Andereck, K. L., and N. G. McGehee. 2008. The attitudes of community residents toward tourism. In Tourism, Recreation and Sustainability: Linking Culture and Environment, 2nd ed.,. ed. S. F. McCool and R. N. Moisey (pp. 236–259). New York: CABI International.

- Aylward, B., K. Allen, J. Echeverria, and J. Tosi. 1996. Sustainable ecotourism in Costa Rica: The Monteverde Cloud Forest Preserve. Biodiversity and Conservation 5: 315–343.

- Ballantyne, R., J. Packer, and K. Hughes. 2008. Environmental awareness, interests and motives of botanic gardens visitors: Implications for interpretive practice. Tourism Management 29(3): 439–444.

- ———. 2009. Tourists’ support for conservation messages and sustainable management practices in wildlife tourism experiences. Tourism Management 30(5): 658–664.

- Ceballos-Lascurein, H. 1996. Tourism, ecotourism, and protected areas: The state of nature–based tourism around the world and guidelines for its development. Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK: IUCN.

- Coleman, J. S. 1958. Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Human Organization 17: 28–36.

- Colewell, M. A., A. V. Dubynin, A. Yu Koroluik, and N. S. Sobolev. 1997. Russian nature preserves and conservation of biological diversity. Natural Areas Journal 17(1): 56–68.

- Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. 2008. Basics of qualitative research, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Doxey, G. V. 1975. A causation theory of visitor-resident irritants: Methodology and research inference. In The Impact of Tourism Sixth Annual Conference Proceedings of the Travel Research Association. San Diego, CA.

- Eagles, P. F. J., S. F. McCool, and C. D. Haynes. 2002. Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas: Guidelines for Planning and Management. A UNEP/IUCN/WTO publication.

- Federal Law #33-FZ. 1995. Federal Law of 03.14.1995 #33-FZ on protected areas (with amendments and additions)/Федеральный закон от 14.03.1995 г. №33-ФЗ «Об особо охраняемых природных территориях» (c изменениями и дополнениями), http://base.garant.ru/10107990/#ixzz35B0XJxOk.

- Fiallo, E. A., and S. K. Jacobsona. 1995. Local communities and protected areas: Attitudes of rural residents towards conservation and Machalilla National Park, Ecuador. Environmental Conservation 22: 241–249.

- Freitag, T. 1994. Enclave tourism development for whom the benefits roll? Annals of Tourism Research 21(3): 538–554.

- Goodman, L. A. 1961. Snowball sampling. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 32(1): 148–170.

- Goodwin, H. J. 1996. In pursuit of ecotourism. Biodiversity & Conservation 5(3): 277–292.

- Goodwin, H. J., I. J. Kent, K. T. Parker, and M. J. Walpole. 1997. Tourism, Conservation and Sustainable Development: Volume IV, The South–East Lowveld. Sustainable Development, Vol. IV. Zimbabwe.

- Gray, P. A., E. Duwors, M. Villeneuve, S. Boyd, and D. Legg. 2003. The socioeconomic significance of nature-based recreation in Canada. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 86: 129–147.

- Kruger, O. 2005. The role of ecotourism in conservation: Panacea or Pandora’s box? Biodiversity and Conservation 14: 579–600.

- Mbaiwa, J. E., and A. L. Stronza. 2011. Changes in resident attitudes towards tourism development and conservation in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Journal of Environmental Management 92(8): 1950–1959.

- McCool, S. F. 2009. Constructing partnerships for protected area tourism planning in an era of change and messiness. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 17: 133–148.

- Newsome, D., R. K. Dowling, and S. A. Moore. 2004. Wildlife Tourism. Clevedon, UK: Channel View Publications.

- Ostergren, D. M., and S. J. Hollenhorst. 1999. Convergence in protected area policy: A comparison of the Russian zapovednik and American wilderness systems. Society and Natural Resources 12(4): 293–313.

- Saarinen, J. 1998. Wilderness, Tourism Development, and Sustainability: Wilderness Attitudes and Place Ethics. In Personal, Societal, and Ecological Values of Wilderness: Sixth World Wilderness Congress Proceedings on Research, Management, and Allocation, Volume I. In Proc. RMRS-P-4, ed. A. E. Watson, G. H. Aplet, and J. C. Hendee (pp. 29–34). Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

- Shultis, J. D., and P. A. Way. 2006. Changing conceptions of protected areas and conservation: Linking conservation, ecological integrity and tourism management. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 14(3): 223–237.

- Spreen, M. 1992. Rare populations, hidden populations and link-tracing designs: What and why? Bulletin Methodologie Sociologique 36: 34–58.

- Walpole, M. J., and H. J. Goodwin. 2001. Local attitudes towards conservation and tourism around Komodo National Park, Indonesia. Environmental Conservation 28(2): 160–166.

- Watson, A., V. Martin, and C. C. Lin. 2009a. Wilderness: An international community knocking on Asia’s door. Journal of National Park (Taiwan) 19(4): 1–9.

- Watson, A., D. Ostergen, P. Fix, B. Overbraugh, D. McCollum, L. Kruger, M. Madsen, and H. Yang. 2009b. Protecting ecotourism resources in a time of rapid economic and environmental transformation in Asia. In Strategic Management Engineering: Enterprise, Environment and Crisis. Proceedings of 2009 International Conference of Strategic Management, eds J. Xiaowen, X. Erming, and I. Schneider (pp. 185–201). Chenghu, Sichuan, China: Sichuan University Press.

- Weiner, D. R. 1999. A Little Corner of Freedom. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Zavadskaya, A. V., and V. A. Sazhina. 2012. From natural to sustainable tourism: Case sociological studies in Protected Areas of Kamchatka. Russian Journal of Ecotourism 4: 22–30.

- Zavadskaya, A. V., and V. M. Yablokov. 2013. Ecotourism in Protected Areas of Kamchatka: Problems and prospects. Moscow: KRASAND.

ELENA NIKOLAEVA works as an expert with nature protected areas to increase their capacity in environmental education, ecotourism, and cooperation with local communities. In 2010–2012 she was a Fulbright scholar at the University of Montana where she received a master’s degree in parks, tourism, and recreation management. Elena is a World Commission on Protected Areas regional vice chair for North Eurasia; email: nikol.elena@gmail.com.

ANNA ZAVADSKAYA is a senior scientist in Kronotsky State Natural Biosphere Reserve, PhD in geography. Her fields of interest include recreational impacts and management, assessment of ecosystem services provided by protected areas, and issues of cooperation with local communities. The main focus of her projects is Kamchatka; email: anya.zavaskaya@gmail.com.

VARVARA SAZHINA lectures at Moscow State University, Faculty of Public Administration. She studied social geography and has PhD in social science. Varvara has been involved in several projects with Kronotsky State Natural Biosphere Reserve and South- Kamchatka Sanctuary since 2011; email: basia@hotbox.ru

ALAN WATSON is the supervisory research social scientist at the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute in Missoula, Montana, on Fulbright assignment to Smangus, Republic of China.