Soul of the Wilderness

April 2015 | Volume 21, Number 1

BY VANCE G. MARTIN and ANDREW MUIR

Wilderness Conservation Leader and Icon Dr. Ian Player, globally recognized wilderness and conservation legend, passed away peacefully on November 30, 2014, at age 87, at Phuzamoya, his family homestead in the KwaZulu-Natal Province of South Africa. Dr. Player was a wilderness conservation pioneer, a visionary, and an activist who profoundly influenced conservation and changed the lives of countless people in his native South Africa and around the globe.

Beginning humbly in the post-WWII days of nature conservation in Africa, working for months on end in the wilderness, Ian climbed the conservation ladder of leadership and influence first in his own country and then internationally, battling resource exploiters to save the best remaining areas while introducing the concept and reality of “designated” wilderness in Africa (Linscott 2013). Ultimately his influence and examples extended globally as he helped establish wilderness organizations in other countries, initiated the World Wilderness Congress (WWC), mentored and inspired many current and future conservation leaders, and changed the lives of countless others through his written and spoken words and personal encouragement.

His list of awards and prestigious recognitions is extensive, including Knight in the Order of the Golden Ark (Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands); Gold Medal for Conservation (San Diego Zoological Society); Distinguished Meritorious Service (DMS), the Republic of South Africa’s highest civilian award; doctor of philosophy, honoris causa – Natal University, South Africa, 1984; doctor of laws (LLD) honoris causa – Rhodes University, South Africa, 2003; and many others.

Getting Started

Ian left secondary school at St. John’s College (comparable to U.S. high school) at 16 to join the army and served in the 6th South African Armored Division with the American 5th Army in Italy from 1944 to 1945. On his return from WWII he worked at various jobs, including on the Durban docks, as a fisherman, and underground in the gold mines before finally getting a job as substitute game ranger working in the remote country of Natal (now KwaZulu Natal) Province for the Natal Parks Board. In that organization he ultimately rose to the rank of chief conservator of Zululand before resigning in 1974 to focus his energies on the wilderness movement. In this next phase of his life’s work, he worked zealously to protect wilderness and nature, and ultimately was appointed a Natal Parks (governing) board member, the only Parks board staff person ever to do so – and he was reappointed three times. Later in life he also served on the board of SANParks Parks, the South Africa National Parks board.

Men, Rivers, and Canoes

As a soldier in Italy during World War II, reflecting on his passion for canoeing, Ian envisioned a difficult 75-mile (120 km) canoe race from the city of Pietermaritzburg to the coastal city of Durban (SA), and by 1951 he had organized such an event. The first race had eight entrants, but he was the only one who finished despite being bitten by a poisonous snake. Ultimately Ian won the race three times, and today more than 12,300 people have competed in what is now the annual Dusi Canoe Marathon. Ian’s canoe adventures are described in his book Men, Rivers and Canoes (1964).

Saving the Southern White Rhino

From 1952 going forward, as warden of the iMfolozi Game Reserve, Ian Player spearheaded several important and far-reaching initiatives. The reserve was established in the 1890s to protect an estimated two to three dozen still-remaining wild southern white rhinos. In a 1953 aerial survey Ian found that their numbers in the reserve had grown to more than 400; however, increased hunting, poaching, farming, and the potential for disease made the herd’s future survival uncertain. Ian Player addressed this challenge directly, consulting with organizations sharing a common interest in rhino conservation to gain their support, and then launched Operation Rhino, leading a team in pioneering the methods and drugs to immobilize these huge mammals for translocation to disperse gene pools in different countries and venues (Figure 1). Many of these captured rhinos were also moved to suitable habitat in their historic distribution range in national parks and game reserves, private game farms, and zoos and parks around the world (Player 1973) – an effort that is widely credited for saving the endangered southern white rhino from extinction, with a current population estimated to be near 20,000.

Figure 1 – Ian Player and his team pioneered methods to tranquilize rhinos for study and translocation to suitable habitat, parks, game farms, and zoos around the world. This effort is largely credited with saving the southern white rhino from extinction. Photo courtesy of the Player family.

Africa’s First Wilderness: Saving Biodiversity and Empowering People

From his first conservation job patrolling in very remote regions and reading material from the wilderness movement in the United States sent to him by wilderness advocate Howard Zahniser, Ian Player learned about the intellectual and legal framework for wilderness protection and about the value of wilderness experiences for the human spirit as well as for biodiversity conservation. Subsequently, as warden for the iMfolozi Reserve, Ian’s tireless advocacy led to zoning parts of the iMfolozi and Lake St. Lucia Reserves as wilderness in the late 1950s – the first protected wilderness areas in South Africa and on the African continent. At the same time, Ian’s desire to understand the personally transformative power of experiencing wilderness was greatly augmented by his exposure to the visionary work of Swiss psychoanalyst Dr. Carl Jung and his friendship with Sir Laurens van der Post, the explorer, author, collaborator with Jung, and ultimately one of the cofounders with Ian of The WILD Foundation. One of the most important aspects of Ian’s exploration of the human psyche was the importance of dream analysis in unlocking personal meaning and growth. He continued this exploration for decades, and helped found the Cape Town Centre for Applied Jungian Studies, the first such center in Africa. When on a wilderness trail with Ian, a first order of business each morning was sharing dreams.

When taking over management of the iMfolosi Reserve, Ian bonded with one of the black game guards, the late Magqubu Ntombela, who became a mentor and friend to him, teaching him the ways of the bush, the culture of the Zulu people, and more. Ian, affected in his early life by the racial prejudice of old South Africa, always credited Magqubu with changing him from that way of thinking, and together they grew to be a legendary force for conservation. This remarkable story is recounted by Ian in his book dedicated to Magqubu, Zulu Wilderness: Shadow and Soul (Player 1998).

In 1955, Ian and his team (including Magqubu) founded the now globally recognized Wilderness Leadership School (WLS) to take people “on trail” – guided wilderness trips of several days in small groups – to personally experience wilderness, and each other. This was especially important for promising young leaders selected by WLS to participate on mixed-race trails, thus pioneering multiracial environmental education during the apartheid era. In the wilderness everyone is equal, and as Ian explained, “Lions don’t care if you’re black or white, man or woman, you’re just a potential meal to them.” Together, Ian and Magqubu personally led hundreds of young leaders as well as established leaders from many countries on trail (Junkin 1987). Friendships formed on WLS Trails provided a nucleus from which many collaborative organizations emerged, such as The WILD Foundation (WILD, based in the United States), The Wilderness Foundation South Africa (WFSA), The Wilderness Foundation United Kingdom (WFUK), and the Magqubu Ntombela Memorial Foundation, established by Ian in honor of his friend, colleague, and mentor. Together, this Wilderness Network of five NGOs continues to advance and innovate on Ian Player’s work, expanding wilderness protection according to and beyond his original vision into a powerful global force for wilderness conservation.

The Wilderness Network

Ian and Magqubu wanted to help support wilderness experiences for people of all backgrounds, races, and nationalities. The WFSA was chartered as a South African nonprofit organization by Ian Player in 1972. The WFUK and WILD were chartered in 1974. These organizations, all inspired, encouraged, or launched by Ian Player and led by his colleagues, helped support wilderness experiences for thousands of people over the decades, spawning a global network of conservationists and leaders from all sectors of life committed to saving wilderness and wildlife everywhere on the planet.

Today, The WILD Foundation, led by Vance Martin, is based in the United States but works globally to protect and connect wilderness and people through field projects; wilderness law and policy at all levels of government and the private sector; written, digital, and visual communications;, and cultural initiatives. WFSA and WFUK are also led by colleagues recruited and mentored by Player: Andrew Muir (WFSA) and Joanne Roberts (WFUK). Their programs focus respectively on African and UK conservation, social intervention, experiential education, and advocacy for protecting wildlands and wilderness, uplifting the lives of citizens, and stimulating environmental ethos among current and future leaders. Andrew Muir worked alongside and was mentored for two decades by Ian Player, and WFSA has become a major force for conservation in southern Africa. Andrew has been globally recognized in his own right for his work integrating social issues with nature conservation solutions. Until very recently, Ian Player continued to serve on the network’s boards and otherwise continued encouraging, guiding, and directing them toward a seminal vision of expanding global wilderness that he and Magqubu conceived so many years ago. Despite a lifelong physical challenge posed by an injured leg that steadily deteriorated with age, Ian worked tirelessly for wild nature to the very end of his life.

The World Wilderness Congress

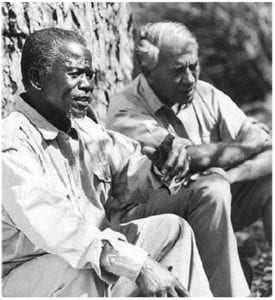

The most internationally far-reaching of Dr. Player’s creations for global wilderness protection was conceived with Magqubu in 1974 while sitting on the banks of the iMfolozi River (Figure 2). As Ian describes, Magqubu turned to me and said, “We are doing good work, but we need to do more. We should call an INDABA-KULU, a great gathering, for all people to come together for wilderness.” Ian and his colleagues, by then including influential leaders in many countries who had gone on trail with him and Magqubu, answered the call, and the first WWC convened in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 1977, again defying the apartheid laws by having all races on a single platform. The next WWC followed in Australia (1980), where Ian met Vance Martin. With Ian’s initial guidance, Vance organized the 3rd WWC in Scotland (1983). Since then, seven more World Wilderness Congresses have convened every three to four years, implemented by Martin as president of The WILD Foundation on behalf of the Wilderness Network. The World Wilderness Congress now constitutes the planet’s longest-running international conservation project and public environmental forum. (For accomplishments of the WWCs, see www.wild.org.) Ian Player opened all the Congresses until the 9th in Mexico 2009, when declining health interfered, and Magqubu participated in both the 1st and 4th (USA) Congresses before his death in 1992.

Figure 2 – Ian Player founded the World Wilderness Congresses that have now convened 10 times in various countries, but he credits his Zulu friend Magqubu Ntombela with the idea, urging him to call an INDABA-KULU, a great gathering for people to come together for wilderness. Photo courtesy of the Player family.

Vance Martin: My Personal Experience with Ian Player

Ian walked across the foyer at the 2nd WWC in Cairns, Australia, in 1980, looked me in the eye, shook my hand, and said, “You’re Vance Martin, you live in Scotland at the Findhorn Foundation and I want to know all about it, and you. Please join Laurens van der Post and me tonight to tell stories. We want to hear yours.” This was very heady stuff for me, a 31-year-old who had quit university forestry studies to study English literature, thinking at the time that no one else could understand what I actually felt about nature and what I might want to do with my life, except maybe Laurens van der Post – whose books had held me rapt since I was a teenager – and, as I was soon to learn, Ian Player.

The encounter felt fateful. Ian’s gravitas was impossible to ignore, conveying at once a sense of imposing leadership, practical accomplishment, and intellectual depth. I was soon to learn and appreciate that the gravitas was well balanced by a deep sense of humor as bawdy and ironic as it was infectious. And so it began.

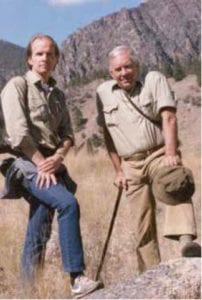

In 1984, I returned to the United States to build The WILD Foundation. Ian’s offer was characteristic: “There’s no money, you’ll need to raise it. I’ll help.” For many years, Ian and I traveled and worked together in Africa, Europe, Russia, Central Asia, India, Australia, and North America, meeting people, exploring country and culture, and searching possibilities for protecting wilderness (Figure 3). Finances were always very tough, and, for many of those years, Ian’s identity as a South African was also a burden, despite his documented disagreement with apartheid. The stain of “apartheidby- association” often affected how he was treated, with people ignoring his personal example of multiracial wilderness programs and his collegial work with Magqubu, regarding him as an apartheid collaborator simply because he lived in South Africa. But we persevered together under WILD’s expanding aegis to promote the wilderness concept as a globally relevant idea for international nature conservation, despite opposition from resource extraction industries, and even some environmental quarters where wilderness was considered impractical in all but a few countries.

Figure 3 – Vance Martin and Ian Player traveled together around the world meeting people and exploring wilderness and its protection. Here they are in the River of No Return Wilderness in Idaho, United States. Photo by John Hendee.

Working strategically through the WWC, with help and support from the increasing numbers and influence of delegates who have participated in the 10 Congresses hosted in 8 different countries, WILD and the Wilderness Network helped create a framework and tools for advancing wilderness as a global idea, including an accepted international definition of wilderness as a protected area category, now recognized by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature; creation of a Wilderness Specialists Working Group within the World Commission on Protected Areas; and many publications providing a wilderness tool kit for policy makers and managers, including a Handbook on International Wilderness Law and Policy, a Wilderness Management textbook (four editions), an International Journal of Wilderness (for 20 years now, www.ijw.org), publications on tribal/community wildlands, and an archive of proceedings, scientific, and popular publications spawned by the WWCs.

These strategic actions supporting global wilderness, evolving from the Congresses and implemented by WILD on behalf of the Wilderness Network and many other collaborators in support of Ian’s vision, have helped a growing number of nations (now 11) create national de jure designation of protected wilderness, and many more nations creating de facto wilderness protection through area planning and policies.

Even though he grew up professionally in the rough-and-tumble of postwar nature conservation in Africa, Ian emphatically espoused the spiritual values of experiencing wilderness and was one of the first major resource managers to repeatedly use the word spiritual in his presentations on the importance and benefits of protecting wilderness. This was also a core part of what I felt about nature, and contributed to the glue that bonded Ian and me.

It was the unique combination of the sacred and the profane, spiritual and practical, that characterized Ian, befuddled his critics, and informed his decisions and accomplishments. For example, in one of his last official acts before resigning from the Natal Parks Board Ian placed the white rhino back on the hunting list. Years later when I asked him why, he was clear: “I don’t understand why someone would want to shoot one of those magnificent beasts. But hunting has a role in conservation, and the fee paid by one hunter for that animal is enough revenue to enable a private owner to keep his land wild for another year, rather than convert it to intensive agriculture or mono-culture tree plantations. There’s no choice in that for me.”

Over 34 years after first sharing our stories at the 2nd WWC, Ian, like a great tree, has fallen to the ground. Despite the ample warning we could see in his gradual decline, his death – like that of a great tree – will leave a gaping hole in the canopy. But that hole is being filled by a host of people who were inspired, energized, and informed by his presence, example, and undying commitment to a world in which wild nature and humans exist and evolve together. I will deeply miss him!

Andrew Muir: My Personal Experience with Ian PlayerI remember meeting Ian for the first time in his study at his home in the Karkloof, introduced by our mutual friend Dr. Ian McCallum. It was 1987 and I was a 22-year-old without a job and had just completed a 400 km (248 mile) youth leader expedition with a racially mixed group of young South Africans down the western coastline of South Africa. Ian was not necessarily impressed by the expedition itself but instead by the fact that I had raised the funds for the event, and that we made this leadership course happen despite breaking a number of apartheid laws at the time.

I had a love for wild places and a desire to find ways to help heal the wounds of apartheid and reunite people with nature and wildlife. Ian gave me the opportunity to realize my dreams by offering me a position at the newly formed Wilderness Leadership School in Cape Town, to begin and run their trail programs there full-time. He employed me with the words, “I can give you ZAR500 ($45 US) per month for the first six months, but after that you must raise your own funds.” How could I refuse such an offer?

By the mid 1990s, I had taken over running the WLS out of Durban, and in 2000 Ian handed over the reigns of the WFSA to me. Since then we have expanded the organization’s influence through holistic social intervention strategies, incorporating a powerful wilderness and conservation ethos into successful projects targeted specifically at vulnerable youth. The WFSA is built on the values of respect for all living things, a passion for conservation and education, integrity and transparency, sustainability, and innovation.

Following Ian’s vision, the conservation projects pioneered, supported, or managed by the WFSA featured protected areas, ensuring such areas and reserves are well managed and are providing benefits for their surrounding communities. The success of Ian’s work through Operation Rhino is in danger of being reversed by the resurgence of poaching, with a rhino being poached every eight hours each day. The Forever Wild Conservation Program, launched in 2011 by the WFSA and Wilderness Network in response to the rhino poaching crisis, works tirelessly toward the protection of all rhinos, maintaining populations of free-ranging rhinos within state and privately managed conservation areas.

Ian worked tirelessly until his last day, fully committed to his life’s work of nature conservation.

Due to the HIV/AIDS pandemic throughout the continent of Africa, huge numbers of youth were left orphaned and vulnerable, stuck in a cycle of poverty with little hope of a brighter future. There was a dire need for holistic (well-balanced) social intervention programs that could offer these youth a chance at becoming successful contributors to society through their education, personal growth, and training, all leading to future employment. Through various social intervention projects (including the Umzi Wethu academies) conducted by the WFSA, young people are being prepared and empowered to become financially independent entrepreneurs and breadwinners for their families.

South Africa’s history has confined most South Africans to townships or degraded rural areas and has fractured traditional cultures. Even today, experiences in nature reserves are beyond the economic reach of most South Africans. The WFSA pioneers, supports, or manages a number of leadership and experiential education projects that aim to develop ecological leadership in the country’s youth and senior decision makers. Through experiential education, thousands of youth, community leaders, and others are able to rediscover their natural heritage every year. This leads to personal growth and a greater understanding of conservation in its broader context.

Since meeting Ian Player at his family homestead 27 years ago, I have been engaged in work responding to his vision, personal inspiration, and the opportunities and challenges to which they led me. WFSA projects and initiatives have directly impacted and uplifted more than 100,000 people, mostly South Africans from previously disadvantaged backgrounds. My deep friendship and bond with Ian was founded on our shared belief that a direct experience of nature, ideally in wilderness, was the best way to inspire individuals to the highest ideals of conservation.

By continuing this work I will honor his legacy.

A Tireless Wilderness Icon

Despite physical challenges that hounded him all his life, Ian worked tirelessly until his last day, fully committed to his life’s work of nature conservation (Figure 4) and his quest to understand the human spirit and psyche. His legacy is without parallel; his example without equal.

Figure 4 – In Ian Player’s final trip in the iMfolozi wilderness. As he neared the trailhead to depart, a large southern white rhino bull emerged from the bush – as if in a final tribute to Ian for saving his kind from extinction. Photo by Margot Muir.

References

Linscott, G. 2013. Into the River of Life: A Biography of Ian Player. Jeppestown, South Africa: Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Junkin, E. D., ed. 1987. South African Passage: Diaries of the Wilderness Leadership School. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Player, I. 1964. Men, Rivers and Canoes. Fish Hoek, South Africa: Echoing Green Press CC.

———. 1973. The White Rhino Saga. New York: Stein and Day, Inc.

———. 1998. Zulu Wilderness: Shadow and Soul. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

VANCE G. MARTIN is president of The WILD Foundation based in the United States, and international director of the World Wilderness Congresses and their legacy of generating important conservation initiatives in the host nations and beyond. He was a close colleague and confidant of his mentor Ian Player for 34 years; email: vance@wild.org.

ANDREW MUIR is CEO of The Wilderness Foundation South Africa and former CEO of the SA Wilderness Leadership School. A close colleague and confidant of his mentor Ian Player for 25 years, Andrew expanded wilderness experiences into successful social intervention programs (such as Imbewu and Umzi Wethu) to train and place former township youth in South Africa’s tourism and conservation industry. Andrew received the prestigious Rolex Award and is a Schwab Foundation Fellow (Africa) for his conservation-social action leadership initiatives; email: andrew@sa.wild.org.