Understanding and Mitigating Wilderness Therapy Impacts: The Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Case Study

Stewardship

August 2018 | Volume 24, Number 2

PEER REVIEWED

ABSTRACT Studies demonstrate that wilderness therapy programs can be beneficial for participants; however, little research has explored the ecological impacts of these programs. A prominent wilderness therapy organization utilizes vast tracts of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (GSENM) for programming. This study examines the specific ecological impacts stemming from the program in GSENM, concurrently with a content analysis of the training procedures administered by the organization. Results emphasize the need to improve education, training, and mitigation measures to minimize impacts stemming from this and other wilderness therapy programs in GSENM, as well as other wilderness areas in which these programs operate

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (GSENM) contains more than 1,866,000 acres (755,143 ha), which are managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). GSENM is the first national monument to be managed by BLM and the last place in the continental United States to be mapped. The area contains stunning landscapes, unique topography, and ecosystems containing natural, cultural, and paleontological resources that facilitate varied recreational and commercial opportunities. GSENM is situated within an area surrounded by protected areas that are managed by other federal entities, such as the US Forest Service and National Park Service.

This area contains numerous designated wilderness areas, and within GSENM, the BLM manages 16 wilderness study areas, which require that management retain the wilderness character of the areas by maintaining naturalness while providing outstanding opportunities for recreation (GSENM Management Plan 2000). Recreational opportunities in GSENM include activities such as camping and backpacking, climbing and canyoneering, off-highway vehicle (OHV) use, hunting, fishing, stock use, and education and interpretation, which all have the potential for social and ecological impacts to the fragile ecosystem (Cole and Wright 2004). Numerous permits are issued for various uses including commercial entities such as livestock grazing and outfitter and guide operations as well as science-related permits. With regard to geographic scale and temporal use, one of the largest commercial operation entities provides wilderness therapy within GSENM and neighboring public lands/protected areas and operates year-round.

Despite the documented positive influences programs such as this can have on human well-being (e.g., Behrens, Santa, and Gass 2010; Bowen, Neill, and Crisp 2016; Kilburn 1999), there is very little understanding of the ecological impacts associated with these frequent, extended, and year-round types of backcountry programs (Russell and Hendee 2000a). Thus, there is a lack of understanding regarding which programmatic activities can cause impacts, and what might be done in the future to mitigate impacts in GSENM and other protected, predominantly backcountry areas. The wilderness therapy program’s staff manual includes minimum-impact practices and standards that are to be followed by staff and participants to minimize environmental impact, but no previous study has examined how closely these practices are followed.

Study Purpose

The purpose of this study is to document the ecological impacts specifically attributed to a wilderness therapy program in GSENM over the span of three years, while also conducting a content analysis of the current training and operational practices established by the program. Associated with this purpose is the degree to which the wilderness therapy program’s dispersed camping practices effectively prevent long-term ecological impacts, which is defined as any disturbance that cannot recover to near-natural and nondiscernable conditions within one year (Marion 2016). This is accomplished by dispersing camping activities to levels that prevent the creation of lasting vegetation and soil impact, or by shifting camping to highly resistant substrates (e.g., rock or gravel). Study results can be used to decrease the wilderness therapy program’s environmental impacts and help sustain the continuation of a positive relationship between the wilderness therapy program and GSENM. The results from this case study also have the potential to inform special use permitting and minimum-impact educational practices associated with wilderness therapy programs.

Wilderness Therapy

Wilderness therapy is an emergent field of health care for youth and young adults who struggle with high-risk behavioral, physical, and mental health risk factors, such as mental illness, substance abuse, and unhealthy body weight or self-image (Tucker, Norton, DeMille, and Hobson 2016). These programs utilize the mental health healing characteristics of nature, along with organized group therapy, to assist participants in making healthy changes (Davis-Berman and Berman 2008). Wilderness therapy has the potential to be a viable option for individuals who might be less responsive to traditional clinical, or indoor methods of treatment (Lariviere et al. 2012). During this type of therapy, participants learn the skills needed to travel and live in the wilderness through extended periods of time spent in the outdoors (Tucker et al. 2016), which have been linked to improved psychological well-being for youth and adults (Behrens, Santa, and Gass 2010; Gass, Gillis, and Russell 2012; Hoag, Massey, Roberts, and Logan 2013; Norton et al. 2014). Research suggests that these types of programs are increasing on public lands (Ewert, Attarian, Hollenhorst, Russell, and Voight 2006; Hoag, Combs, Roberts, and Logan 2016; Russell and Hendee 2000b), and according to the National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs (NATSP), there are more than 20 of these accredited programs facilitating wilderness-based therapy in protected areas across the United States (NATSP 2015). Although 20 programs may seem minuscule, when you consider the geographic expanse, group sizes, duration of stays, and often year-round use of the protected areas where these programs operate, their potential footprint is immense.

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and Wilderness Therapy

The wilderness therapy concessionaire in GSENM has a long, positive history with monument management, facilitated by frequent communication between the two parties. Wilderness therapy participants engage in nature-based, guided, and facilitated therapy in GSENM and some of the surrounding protected areas for several weeks, moving in small groups to different backcountry camping locations each day. Therefore, participants spend an extensive amount of time over a large expanse of GSENM. The therapy program provides training to staff and has specific outdoor practices they recommend via their staff manual, but there is little to no understanding of the impacts this commercial operation has on the ecological resources of the monument.

Like many land managers who are attempting to provide recreation opportunities while also conserving the unique ecosystems sought by recreationists, the managers at GSEMN must strike a balance between use and allocation of the resources. Specifically, GSENM managers are charged with providing “sustainable recreation” opportunities, defined as those that “provide for environmental sustainability while fulfilling the social and economic needs of present and future generations” (National Landscape Conservation System 2011). Inevitably, recreational use can lead to resource impacts (Hammitt, Cole, and Monz 2015), particularly in areas such as GSENM’s backcountry, which is largely free of managed trails and campsites. Fragile and generally pristine landscapes are extremely vulnerable to even small amounts of recreational use (Cole and Wright 2004; Marion 2016; Marion, Leung, Eagleston, and Burroughs 2016). Specific to wilderness therapy programming, research is scant regarding the minimum impact practices they may promote, and the potential ecological impacts that may result from this type of programming (Ewert et al. 2006; Russell and Hendee 2000a). Furthermore, Russell and Hendee (2000a) suggest that “enhanced communication and cooperation is needed between agency managers and wilderness therapy leaders to coordinate use and address impacts” (p. 141).

Methods

Methods Overview

The researchers used GPS data points that were provided by the wilderness therapy organization to identify locations where their programming may have created backcountry campsite impacts. Researchers then went to these locations to record and quantify ecological indicators stemming from recreational impacts. Subsequently, the researchers used content analysis to examine the wilderness therapy program’s staff manual for instructions regarding resource impact mitigation practices. Finally, content analysis results were compared to the field-based ecological data findings to inform where minimum impact practices could be improved.

GPS Campsite Points

Each day, the wilderness therapy leaders, who are strategically dispersed throughout the GSENM backcountry, send a Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) device signal back to the program’s base, notifying the managers that everything is okay. The PLB provides temporally explicit GPS-enabled data points in each message. Given the vast and largely trail-less landscape, the researchers used these GPS data to determine locations where backcountry campsite impacts may have occurred. A sample of these locations that were sent within the boundary of GSENM between 12:00 a.m. and 6:00 a.m. local time during 2014, 2015, and 2016 were used to establish n=210 sampling locations (i.e., backcountry campsites used by the therapy program). In addition, the number of nights spent at the same location, which was denoted by PLB messages at the same GPS coordinates over the span of one or more days, was also calculated. We note that the wilderness therapy program’s guidance specified that their groups should avoid preexisting campsites and camp only one night in each location. They also avoid travel and camping in areas that receive frequent visitation by regular GSENM visitors, thus there is high confidence that the resource impacts assessed were attributable to the wilderness therapy program.

Backcountry Campsite Ecological Impact Data

At each site, the researchers recorded and quantified ecological indicators, which are attributes that can be inventoried and monitored to track changes in conditions, so that desired conditions can be adaptively managed and maintained. Ecological indicators were collected via a GPS-enabled tablet, which contained attributes of interest that were collaboratively developed by the researchers and GSENM managers. Given Blenderman Fig New 1 the area’s sparse vegetation, lack of organic litter, and widespread naturally occurring exposure of bare soil, traditional recreation ecology indicators, including campsite size, vegetation loss, and soil exposure, could not be applied (Marion et al. 2016). Further, the generally low levels of site use were insufficient to create visually obvious campsite boundaries. An important goal of dispersed camping is to “leave no trace” of your visit so that subsequent campers do not find and reuse the same camping spot, allowing time for natural recovery to occur (Marion 2014).

Figure 1 – The bark from juniper trees is flammable and makes an excellent fire starter when a bow drill is used. However, only a very small amount of the bark is needed so excessive bark stripping is a highly visual “avoidable” impact.

Figure 2 – Wilderness therapy programs often incorporate various ceremonies to recognize youth achievements. Rock art should be removed and natural conditions restored following ceremonies. Furthermore, the right side of this structure was constructed on cryptobiotic soil crusts, which are sensitive to trampling disturbance.

Therefore, the researchers focused on visually obvious indicators of impact that would enable us or other potential campers to identify a spot’s use as a campsite. Ultimately, the following ecological impact indicators were selected based on input from GSENM staff and existing recreation ecology literature: quantities of litter, obvious use areas, dug-up holes (generally, sump holes that were not filled in or have been unearthed by wildlife), scattered charcoal and/or ashes, bark stripping, fire sites (generally visible charcoal and/or ashes, but also fire-created indention with obvious disturbance to the natural rock or soil composition), disturbed cryptobiotic soil and/or crust, tree and/or shrub damage (different from “bark stripping” as evidenced by cut limbs, broken branches, and/or stumps), collected firewood, human waste (different from dug-up holes, as these often include decomposed toilet paper, waste, and sometimes catholes that were not filled in), campsite furniture, and visible visitor-created trails.

Content Analysis of Wilderness Therapy Program Manual

In consultation with the therapy program, the researchers were provided with the staff training manual. A content analysis was employed (see Weber 1990) to examine the manual, specifically seeking interpretive themes that mentioned or explicitly prescribed minimum impact mitigation behaviors for staff and participants. The researchers, who are trained Leave No Trace master educators (see https://lnt.org/learn/master-educator), applied their knowledge of minimum impact practices (also described in Marion 2014), to evaluate the mitigation practices prescribed in the manual. These mitigation measures were subsequently compared to the field-based ecological data and established minimum impact practices developed through recreation ecology research (see Marion 2016) and prescribed through entities such as the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics (see www.LNT.org).

In consultation with the therapy program, the researchers were provided with the staff training manual. A content analysis was employed (see Weber 1990) to examine the manual, specifically seeking interpretive themes that mentioned or explicitly prescribed minimum impact mitigation behaviors for staff and participants. The researchers, who are trained Leave No Trace master educators (see https://lnt.org/learn/master-educator), applied their knowledge of minimum impact practices (also described in Marion 2014), to evaluate the mitigation practices prescribed in the manual. These mitigation measures were subsequently compared to the field-based ecological data and established minimum impact practices developed through recreation ecology research (see Marion 2016) and prescribed through entities such as the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics (see www.LNT.org).

Results

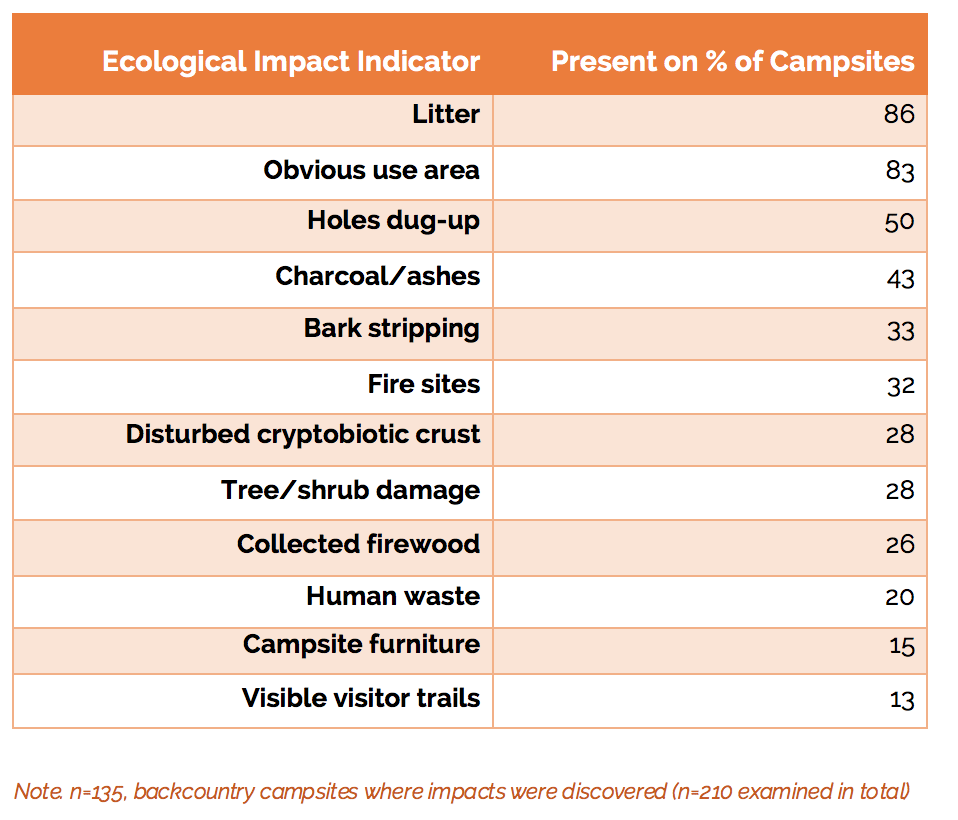

Backcountry Campsite Ecological Indicators

Of the n=210 backcountry campsites, the researchers found evidence of impacts at approximately 64% (n=135) of the sites (Table 1). Litter (trash) was one of the most frequent visitor impacts, visible on approximately 86% (n=116) of the sites. Litter commonly included nylon cord, food wrappers, and feminine hygiene products. Litter items that were less frequent, but also discovered during the research, included burnt or damaged cooking sets, and apparel, such as socks or gloves. At approximately 83% (n=112) of the sites, it was obvious that the sites had been utilized, as evidenced by trenching, decorative construction with natural objects, and broken branches or stripped bark. Dug-up holes were observed on approximately 50% (n=67) of the sites, likely dug to sump dishwater or for burying human waste or food. Scattered charcoal and/or ashes were observed on 43% (n=58) of the sites. Evidence of bark stripping was observed on approximately 33% (n=45) of the sites. Wilderness therapy participants from this program start their campfires with a bow drill, using bark stripped from cedar trees as a fire starter. Fire sites were marked by charcoal and/or ashes, which were observed on approximately 32% (n=43) of the sites. These did not include locations where charcoal and/or ashes had been scattered in off-site areas. Disturbed cryptobiotic soil and/or crust was observed on approximately 28% (n=38) of the sites. Tree and/or shrub damage, including cut branches and stumps, was observed in approximately 28% (n=38) of the sites, and collected firewood was observed on approximately 26% (n=35) of the sites. Human waste was observed on 20% (n=27) of the sites, often marked by toilet paper and/or unfilled or dug-up holes, and some was surface disposed. Campsite furniture was observed on approximately 15% (n=20) of the sites, often in the form of large sitting logs or as ritualistic/artistic structures. Finally, visible visitor-created trails were observed on approximately 13% (n=17) of the sites.

Figure 3 – After locating each wilderness therapy camping spot with a GPS unit, they were assessed with 16 inventory and 21 impact indicators. A phone app was used to record all data and photographs.

Figure 4 – Trash left behind was one of the most visually obvious clues that aided field staff in relocating the wilderness therapy campsites.

Backcountry Campsite – Nights Occupied

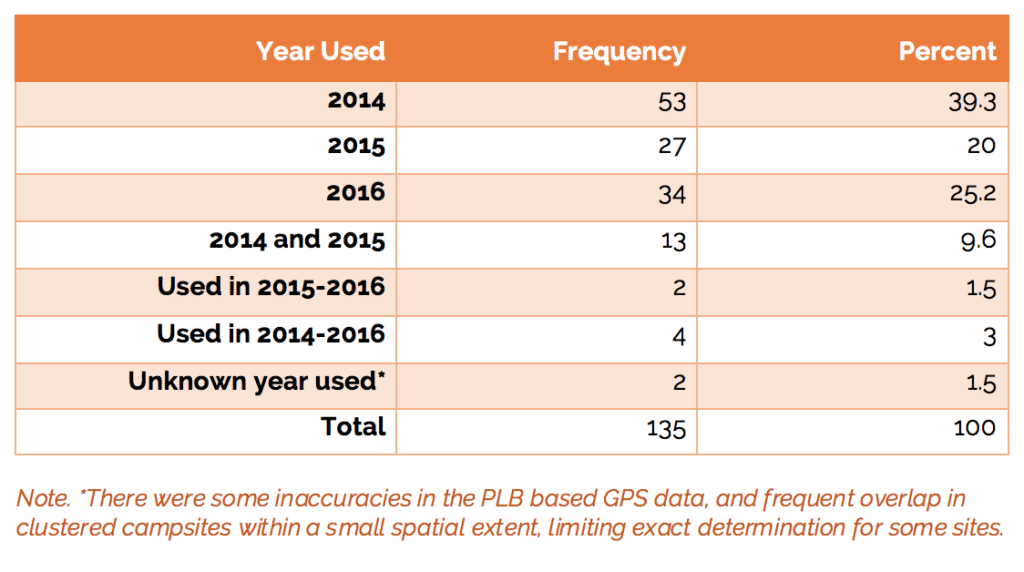

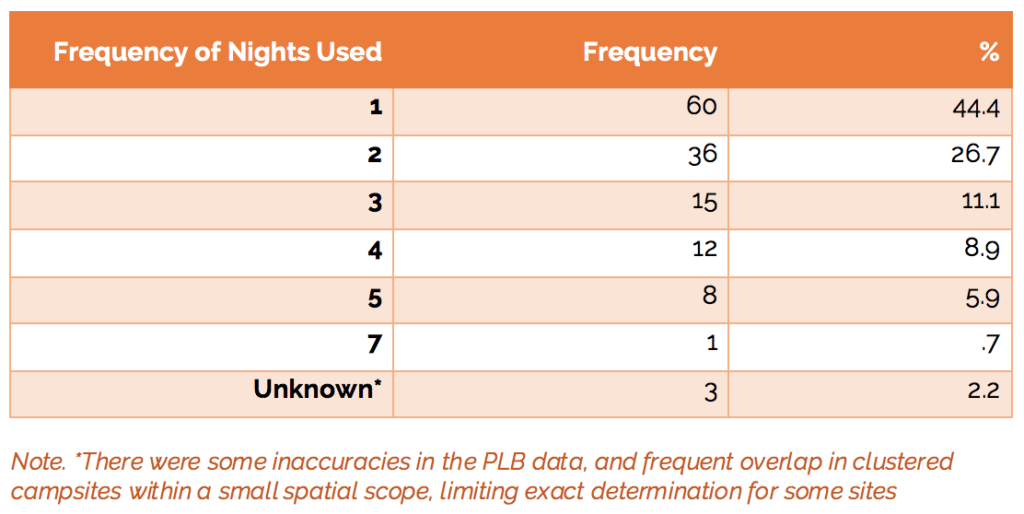

Table 2 – Frequency and percentage of nights campsites were used by therapy programs across 2014, 2015, and 2016

Forty-four percent (n=60) of the 135 impacted campsites were occupied only one night between 2014 and 2016 (Table 2). However, the wilderness therapy programs occupied many other campsites for multiple nights between 2014 and 2016. For example, 26% of the campsites (n=36) were occupied for two nights, 11% (n=15) were occupied for three nights, 9% (n=12) were occupied for four nights, and 6% (n=8) were occupied for five nights.

Approximately 39% (n=53) of sampled campsites were used in 2014 (Table 3). Approximately 25% (n=34) of all campsites examined were occupied in 2016, and around 20% (n=27) were occupied in 2015. It was determined that the therapy program occasionally uses the same sites in back-to-back years. For example, several of the same sites were occupied in 2014 and 2015 (~10%; n=13), and four sites (3%) sampled were used during all three years. Ideally, staff would avoid using any camping spot showing prior signs of use and impact, even from prior years.

Content Analysis of Wilderness Therapy Program Manual

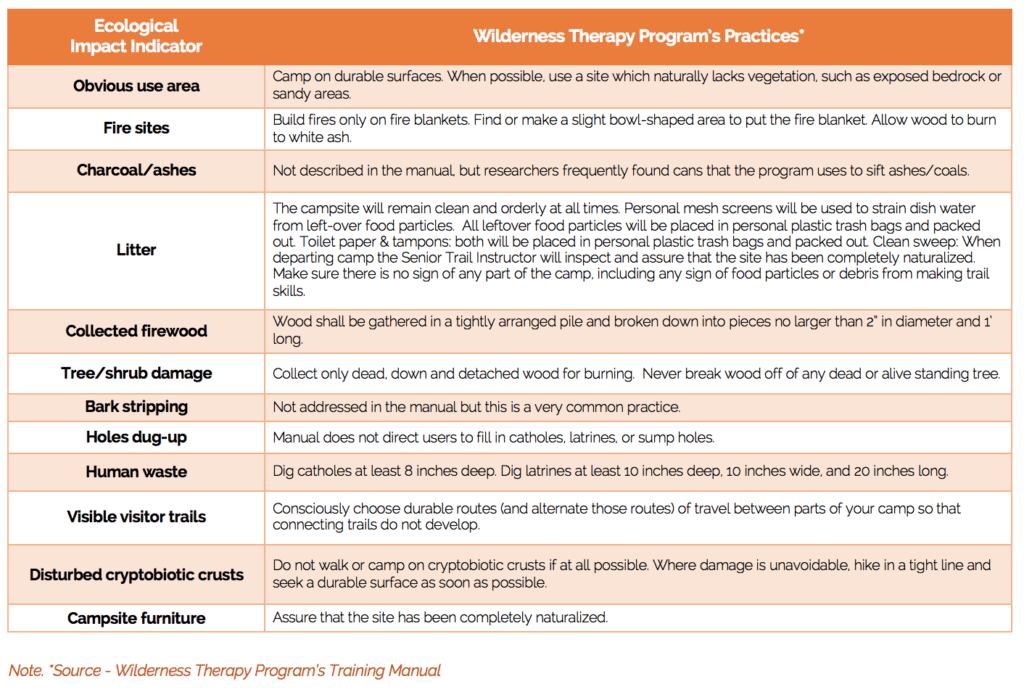

The content analysis of the wilderness therapy program’s staff training manual revealed that the following ecological impacts were addressed with staff protocols: litter, obvious use areas, fire sites, disturbed cryptobiotic soil and/or crust, tree and/or shrub damage, collected firewood, human waste, campsite furniture, and visible visitor-created trails (Table 4). Practices concerning dug-up holes, charcoal and/or ashes, and bark stripping were not provided within the manual.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to document the ecological impacts attributed to a wilderness therapy program in GSENM from three years of use-history data, while also conducting a content analysis of the current practices established by the program. At approximately 64% of the campsites sampled, the ecological impact indicators that were documented suggest that the practices found in the therapy program staff manual are not always being followed consistently or to the full extent possible. Many of the measured impact indicators discovered at the sampled campsites represent “avoidable” forms of impact when staff and participants apply minimum impact practices (e.g., Leave No Trace) applicable to dispersed camping (Marion 2014). Nine of the twelve impact-related behaviors are included in the practices contained in the wilderness therapy program’s official staff manual. This suggests that improved oversight and evaluation of the field staff’s teaching and adoption of minimum impact practices is necessary. However, the manual does not include mitigation instructions for 3 of the 12 impact indicators (dug-up holes, charcoal and/or ashes, and bark stripping), which can be informed through existing literature (e.g., Cilimburg, Monz, and Kehoe 2000; Hammitt, Cole, and Monz 2015; Hendee and Dawson 2002; Marion 2014; Marion, Leung, Eagleston, and Burroughs 2016) and current backcountry-focused recommendations prescribed by GSENM. Inclusion of these additional practices into the staff manual and trainings could improve these results. Furthermore, programmatic changes that lessen or even eliminate some of the current practices, such as bark stripping for fire starting, may be warranted.

Some of the existing mitigation practices are working, as at n=75 of the sites the researchers were not able to locate impacts. The landscape features and ecological resilience of the study areas are largely the same throughout. Therefore, we attribute this success to more conscientious staff and/or participants who: (1) camped a single night at each spot, (2) applied the low impact camping practices to avoid leaving visually obvious resource impacts, and (3) cleaned and restored their camping spots prior to moving on. Cleaning up litter, disassembling and dispersing the decorative materials, and filling in dug-up holes would have substantially increased the number of these “successful” dispersed camping spots.

An additional goal of this study was to examine the degree to which the wilderness therapy program’s dispersed camping practices effectively prevented long-term camping disturbance. As noted earlier, successful application of the dispersal strategy requires that visitors do not repeatedly reuse the same campsites. For the years of available data (2014–2016), more than 55% of the sampled campsites were used more than once. Only approximately 44% of the campsites were occupied a single night, although it is possible that some were used in the years preceding 2014. Repeat use of individual sites and the clustering of campsites are problematic for achieving success under a dispersed pristine site camping strategy.

Conclusion and Suggestions

Findings indicate that some of the wilderness therapy field staff and participants are not following the program’s established procedures as fully as possible. This could be due to ineffective teaching methods, student’s ability to listen and learn, or their staff’s ability to ensure that participants follow low impact camping practices included in the manual. The program does have an extensive staff training protocol that is working to mitigate ecological impacts. Additional emphasis on minimum impact practices could be helpful, along with updated training and staff manual revisions to include the additional indicators discussed in this study (i.e., dug-up holes, charcoal and/or ashes, and bark stripping).

The findings reveal considerable amounts of repeat use of dispersed camping locations, which creates lasting impacts that do not recover in a single year. To avoid long-term impacts, recreation ecology studies reveal that campsites can only be used once or twice in a given year, with visitors avoiding all spots that exhibit prior evidence of camping (Marion, Leung, Eagleston, and Burroughs 2016). It is understood that field staff may not always be able to comply with such practices when extreme and unsafe weather events, participant injury, slower than expected travel times, or other similar situations occur. Therefore, the wilderness therapy program could identify, within each commonly used area, a designated campsite for use whenever a group is unable to move each night and use those sites only when repeated camping at one location is necessary. Recreation ecology research suggests that concentrating repeat use on a single site within each area will result in far less cumulative impact than would camping many times per year on a larger number of dispersed campsites (Marion 2016), although the degree of impact can vary by activity, intensity, and location.

To avoid long-term impacts, recreation ecology studies reveal that campsites can only be used once or twice in a given year, with visitors avoiding all spots that exhibit prior evidence of camping

Finally, unannounced field checks conducted by knowledgeable program managers could be introduced to promote improved implementation of the program’s low impact procedures. To continue fostering the positive relationship between GSENM managers and the therapy program, managers at both organizations could frequently meet to discuss any changes in protocols or resource conditions, so that adaptive management strategies can be implemented and evaluated in a timely manner.

Wilderness therapy clearly has a place in our protected areas, and research has demonstrated the positive impact these programs can have on human health and well-being (Behrens, Santa, and Gass 2010; Bowen, Neill, and Crisp 2016). But, without sustainable practices, these programs have the potential to damage the environments that promote well-being. With more than 20 accredited programs scattered across the United States, it is important that wilderness therapy programs continue to understand the impacts associated with their behavior and follow protocols to mitigate both ecological and social impacts. This study helps to fill that gap; however, further research is warranted. Federal- and state-protected area managers, national organizations such as the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics, the NATSP, and wilderness therapy programs should strive to continue collaborating with researchers to establish best practices. Once developed, these strategies can be disseminated widely and implemented into special use and concessionaire agreements to ensure the long-term well-being of participants as well as the protected areas they use. We also suggest additional research to evaluate the efficacy of staff training offered by wilderness therapy programs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank GSENM staff for their guidance and support of this research. We would also like to thank the therapy program used in this case study.

AMELIA ROMO is a graduate student at Penn State University; email: ameliaib523@gmail.com

B. DERRICK TAFF is an assistant professor in the Recreation, Park and Tourism Management Department at Penn State University; email: bdt3@psu.edu

JEREMY WIMPEY is principal owner of Applied Trails Research, LLC, and research faculty at Penn State University’s Recreation Park and Tourism Management Program in Pennsylvania; email: jeremyw@appliedtrailsresearch.com

JEFFREY MARION is a recreation ecologist with the US Geological Survey at the Virginia Tech Field Station, Blacksburg, VA; e-mail: jmarion@vt.edu

FORREST SCHWARTZ is a postdoctoral scholar in the Recreation, Park and Tourism Management Department at Penn State University; email: fgs117@psu.edu

References

Behrens, E., J. Santa, and M. Gass. 2010. The evidence base for private therapeutic schools, residential programs, and wilderness therapy programs. Journal of Therapeutic Schools and Programs 4(1): 106–117.

Bowen, D., J. Neill, and S. Crisp. 2016. Wilderness adventure therapy effects on the mental health of youth participants. Evaluation and Program Planning 58: 49–59.

Cilimburg, A., C. Monz, and S. Kehoe. 2000. Wildland recreation and human waste: A review of problems, practices, and concerns. Journal of Environmental Management 25(6): 587–598.

Cole, D. N., and V. Wright. 2004. Information about wilderness visitors and recreation impacts. International Journal of Wilderness 10(1): 27–31.

Davis-Berman, J., and D. Berman. 2008. The Promise of Wilderness Therapy. Boulder, CO: Association for Experiential Education.

Ewert, A., A. Attarian, S. Hollenhorst, K. Russell, and A. Voight. 2006. Evolving adventure pursuits on public lands: Emerging challenges for management and public policy. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 24(2): 125–140.

Gass, M., H. Gillis, and K. Russell. 2012. Adventure Therapy: Theory, Practice, and Research. New York: Routledge.

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Management Plan. 2000. BLM/UT/PT-099/020+1610.

Hammitt, E., D. N. Cole, and C. A. Monz. 2015. Wildland Recreation: Ecology and Management, 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hendee, J. C., and C. P. Dawson. 2002. Wilderness Management: Stewardship and Protection of Resources and Values. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Hoag, M., K. Massey, S. Roberts, and P. Logan. 2013. Efficacy of wilderness therapy for young adults: A first look. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth 30: 294–305.

Hoag, M., K. Combs, S. Roberts, and P. Logan. 2016. Pushing beyond outcome: What else changes in wilderness therapy? Journal of Therapeutic Schools and Programs 8(1): 45–56.

Kilburn, K. 1999. Wilderness for healing and growing people. International Journal of Wilderness 5(3): 19–21.

Lariviere, M., R. Couture, S. Ritchie, D. Cote, B. Oddson, and J. Wright. 2012. Behavioral assessment of wilderness therapy participants: Exploring the consistency of observational data. Journal of Experiential Education 35: 290–302.

Marion, J. 2014. Leave No Trace in the Outdoors. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

———. 2016. A review and synthesis of recreation ecology research supporting carrying capacity and visitor use management decision making. Journal of Forestry 114(3): 339–351.

Marion, J., Y. Leung, H. Eagleston, and K. Burroughs. 2016. A review and synthesis of recreation ecology research findings on visitor impacts to wilderness and protected natural areas. Journal of Forestry 114(3): 352–362.

National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs. 2015. Retrieved from https://natsap.org//PDF_Files/2015_2016_Directory.pdf.

National Landscape Conservation System. 2011. 15-Year Strategy (2010–2025). The Geography of Hope. Bureau of Land Management. BLM/WO/GI-11/013+6100.

Norton, C., A. Tucker, K. Russell, J. Bettmann, M. Gass, H. Gillis, and E. Behrens. 2014. Adventure therapy with youth. Journal of Experiential Education 37: 46–59.

Russell, K., and J. Hendee. 2000a. Wilderness therapy as an intervention and treatment for adolescents with behavioral problems. In Personal, Societal, and Ecological Values of Wilderness: Sixth World Wilderness Congress Proceedings on Research, Management, and Allocation, ed. A. E. Watson, G. H. Aplet, and J. C. Hendee. Proc. RMRS-P-14. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 136–141.

Russell, K. C., and J. C. Hendee. 2000b. Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare: Definitions, Common Practice, Expected Outcomes and Nation-wide Survey of Programs. Technical Report 26. Moscow, ID: Idaho Forest Wildlife and Range Experiment Station.

Tucker, A., C. Norton, S. DeMille, and J. Hobson. 2016. The impact of wilderness therapy. Journal of Experiential Education 39(1): 15–30.

Weber, R. P. 1990. Basic Content Analysis (No. 49). Washington, DC: Sage.

Read Next

WILD11: Why China, and Why Now

The 11th World Wilderness Congress (WWC), or WILD11, will convene in China in late 2019. Our China partners have promised exact venue and date for 2019 in September of this year.

Paradigms Lost: A Rumination on the Pursuit of Wildness

Recently, two reissued books from the early 1900s caught my attention. The books are That Summer on the Nahanni 1928: The Journals of Fenley Hunter and Sleeping Island: A Journey to the Edge of the Barrens, by P. G. Downes.

Visitor Experiences of Wilderness Soundscapes in Denali National Park and Preserve

Denali National Park and Preserve (DNPP), home to 6 million acres (2,428,114 ha) of land protected as wilderness, has collected a variety of biophysical acoustic data related to a backcountry management plan.