The Gate and Pulpit Rock, Nahanni River

Paradigms Lost: A Rumination on the Pursuit of Wildness

Soul of the Wilderness

August 2018 | Volume 24, Number 2

Recently, two reissued books from the early 1900s caught my attention. Part of the Forgotten Northern Classics series from McGahern Stewart Publishing, the books are That Summer on the Nahanni 1928: The Journals of Fenley Hunter and Sleeping Island: A Journey to the Edge of the Barrens, by P. G. Downes. I believe such old adventure tales should be considered an important part of wilderness studies literature. The good ones, such as these two, offer an unvarnished look into a pivotal time for wilderness travel and protection. They give us rich descriptions of the very experiences we are trying to save when we protect wilderness. And they can inform us on certain issues that have since become more urgent. These include the persistent need for humans to have contact with wildness, the protection of indigenous cultures threatened with losing that connection, and the profound influence of air travel and communication technology on the pursuit of wildness.

Hunter and Downes

The first of our two accounts, That Summer on the Nahanni 1928, actually chronicles two excursions Fenley Hunter made into, as he put it, “the Western Arctic,” in the 1920s. The first was in 1923, the second in 1928, by which time he was 42 years old. The 1928 journal documents 134 days of arduous travel by motorboat, canoe, and on foot that eventually take Fenley deep into Canada’s present-day Nahanni National Park, down the historically important MacKenzie River, down the Porcupine River through the southeast corner of the present-day Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, into the present-day Yukon-Charlie National Preserve, and as far west as Fort Yukon, Alaska.

At first glance, Hunter seems an unlikely candidate for such projects. He lived near New York City, on Long Island, where he manufactured and sold mechanical signs for buses and trolleys. But somewhere along the way, he caught a terrible case of adventure fever, noting, “I seem to have a great hankering for the unknown in Nature, and in its untouched state it appeals to me greatly” (Hunter 2015, p. 12).

The second book, Sleeping Island, is one of my all-time favorites. It’s a narrative account by P. G. Downes of a long canoe trip into northern Manitoba and present-day Nunavik Territory. Downes was a Harvard graduate and acclaimed teacher at a private boys’ school near Boston who “had long been susceptible to northern yearnings” (Downes 2011, introduction, para. 5). He began taking annual summer trips deep into northern Canada. Sleeping Island is an account of the one he made in 1939. To quote his biographer, R. H. Cockburn: “As a narrative of an arduous canoe trip, “Sleeping Island” has few equals” (Downes 2011, Introduction, para. 10). In it, Downes and his stern paddler, a local trapper named John Albrecht, navigate a bewildering maze of lakes, rivers, rapids, and ancient portages on their way to their main goal, Sleeping Island Lake, now officially known as Nueltin. A good portion of their journey passes through present-day Nueltin Lake Provincial Park.

Figure 1 – Downes in 1940. “His clothes were in tatters. His pack was very small and light, so he had to be tough,” said a mounted policeman who ran into him. Photo courtesy of McGahern Stewart Publishing, Mrs. E. G. Downes, and R. H. Cockburn.

The trips described in both books occurred during a particularly pivotal time both for wilderness exploration and preservation. For wilderness exploration, this was a period during which a lot of amateur explorers were figuring out that they did not need large government grants or connections in the Royal Geographic Society to conduct adventurous voyages of discovery. Also, commercial air travel was just beginning to come into its own but was not to the point of profoundly altering access to wilderness that it would reach after World War II.

As for wilderness protection, the period between the two World Wars (roughly the 1920s and 1930s) will already be known to many as a remarkable time. Among other things, it’s the time during which Aldo Leopold proposed the first designated wilderness on US federal lands; Ernest Oberholtzer would write a rather radical land-use plan for protection of virtually the entire Rainy Lake watershed, better known as the Quetico-Superior Wilderness; and Bob Marshall would spearhead the founding of an organization called The Wilderness Society.

Why They Went

Neither Hunter nor Downes were especially loquacious about their motivations. What they did say suggests that they were not much different from those reported by wilderness users today. Hunter puts a lot of emphasis on his enjoyment of the physical challenges. “There are many compensations for the hardships,” he says at one point, “such as being fit and like a steel trap, the joy of food (any kind and under any condition), and 6 or 7 hours of sleep; … and after a while a kind of resignation to fatigue and discomfort” (Hunter 2015, p. 159).

Downes was more uncertain. To the frequently asked question, “Why?” he found it “very hard to answer.”

It has always seemed to me that, whatever I might say, I was partially dishonest for I gave an incomplete answer and probably not the true one at all. The very apparent reason to myself is that I like it there in the land of the little trees, I like the people, I am happy there. But to any reasonable person this is very inadequate. (Downes 2011).

Both Hunter and Downes collected data as they traveled. Both made hand-drawn maps of the more remote areas they passed through. Hunter made natural history notes and even took a few “specimens” of the indigenous fauna. One day he shot two Dall sheep, which he proudly noted were “the first two ever taken out of the South Nahanni country” (Hunter 2015, p. 147). His small crew ate the sheep meat and Hunter brought back the skin and heads for a scientist friend back in the United States.

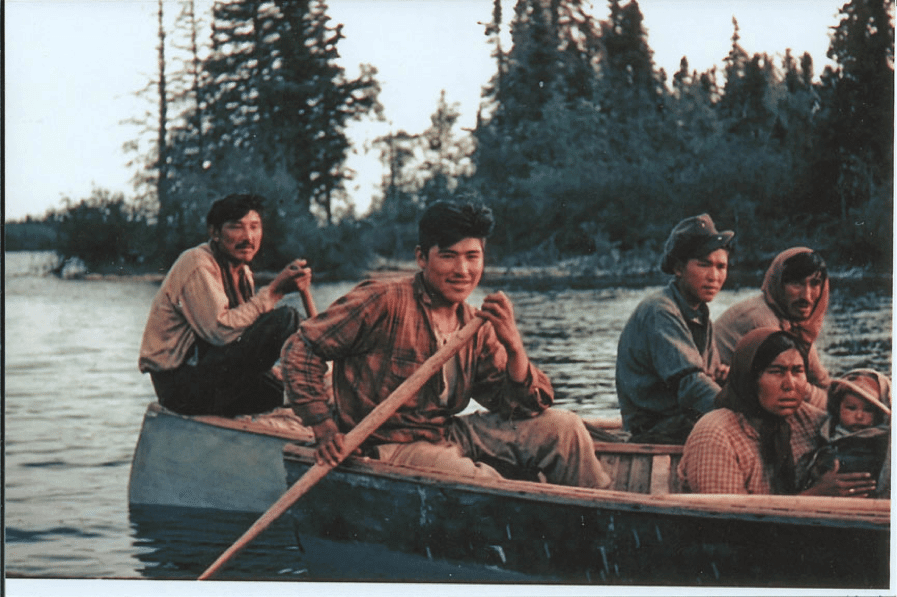

Figure 2 – P. G. Downes with Cree Indian friend Solomon Merasty, en route to Reindeer Lake, 1936. Photo courtesy of McGahern Stewart Publishing, Mrs. E. G. Downes, and R. H. Cockburn.

Downes took no animal specimens (though he did shoot one caribou for some badly needed protein). He did, however, make detailed observations of topography and geology. His keenest academic interest was anthropology, and he reported back rather extensively on the customs and stories of the indigenous people he came across (Cree and Chipeweyan “Indians,” and Caribou “Eskimo”).

For both these two, however, the advancement of knowledge was more an excuse than a primary purpose. Downes hints at this when, after listing his various practical motives, he says, “I am quite sure that without any or all of [them], this particular June would have found me once more leaving my classroom behind, bound North” (Downes, 2011, ch. 1, para. 3).”

We might conclude, then, that the motivations for wilderness travel by these adventurers were much the same as those reported by more recent outdoor enthusiasts – fitness, heightened senses, including taste, aesthetics, and so forth. And that, much like many of us today, Hunter and Downes recognized something intangible and very difficult to explain that also drove them. Perhaps that intangible thing is quite simply, the pursuit of wildness.

Figure 3 – Small party of Barren Land Chipewyans Downes met in 1936. “The woman … had a baby done up in a moss-bag.” Photo courtesy of McGahern Stewart Publishing, Mrs. E. G. Downes, and R. H. Cockburn.

Wilderness and Cultural Protection

Of the two adventurers, Downes seems to have been the more sensitive to big changes occurring even in remote northern Canada. At some points he is eloquent about it, such as the time he comes upon a group of indigenous elders, women, and children whose young men have gone far off on a hunt:

Here was something which in a few short years was destined never to be repeated again: a strange people, a brave people, with a heritage and way of life stretching back through the mist of time to the bleak steppes of Siberia, dying, unable to change, disappearing into the timeless obscurity from whence they had come. (Downes, 2011, ch. 8, para. 36)

Downes would have been pleased that finally, in 2010, the Province of Manitoba set aside 1.1 million acres of the country through which he traveled as Nueltin Lake Provincial Park, “within the traditional territory of Northlands Denesuline First Nations who continue to use it for hunting, trapping, and fishing.” The park also receives a small number of visitors who use the park for wilderness camping (Nueltin Lake Provincial Park Management Plan 2015, p. 5).

Our other early adventurer, Fenley Hunter, was less in tune with issues of rapid change. He seems to have been too absorbed in traveling, mapping, collecting specimens, and enjoying the exercise to ponder anything else. Nevertheless, several wilderness protective sites have been established on the lands he explored. The one he explored most thoroughly, Nahanni, has evolved much differently from that of Downes’s Nueltin. Nahanni’s mountainous landscape, spectacular waterfalls, and deep-cut canyons attract a lot more tourists, thus creating a bit more commotion and the need for more intensive management. There are now seven official plane landing sites in the park, five of them lined up along the corridor of the South Nahanni River. These are mostly used by whitewater paddlers. Most of the remainder of park visitors are “flightseeing” customers there for less than a day.

Air Taxis, Choppers, and Sat Phones, Oh My

Since the days of Hunter and Downes, the wilderness experience has been increasingly affected by air travel and communication technology. It took Hunter and his small party 32 days of strenuous river travel “beyond the steel” merely to reach today’s boundary of Nahanni National Park and Preserve. It then took Hunter 24 more days, even with a small motor, which he would later have to carry over several long portages, to reach his dream destination, a cataract he named Virginia Falls in honor of his daughter back home on the East Coast. For at least a total of 134 days, he had no communication with his family or business back home.

Downes was equally disconnected from the outside world during his trip to Nueltin Lake and back. In fact, he and his partner, Albrecht, were so isolated they made an agreement that in today’s world of satellite phones and helicopters would seem criminal: if one of them got lost or otherwise went missing, the other one would not go looking for him. As Downes explained:

This may seem a curious and brutal agreement…. [But] we both knew that when something really serious happens in a country like this, so vast, so unknown and confusing, the time it takes to get out and get back even with aid is so great, and the possibility of this aid being any use is so small, that it is nothing but a gesture to convention. (2011, ch. 4, para. 43)

The isolation thus experienced by Hunter and Downes meant a complete and uninterrupted immersion in their immediate environment. Today such complete immersion is rare indeed. The point is brought home skillfully in Out There: In the Wild in the Wild Age, a 21st-century adventure book by wilderness journalist Ted Kerasote. It describes a canoe trip Kerasote and a friend took in the early 2000s down the Horton River in the Northwest Territories. It’s a very remote spot, but the remoteness, and wildness, are diminished by the electronic gadgetry they bring along, most notably a satellite phone and GPS system. As Kerasote (2004) notes at one point,

The air taxi’s telephone number is programmed into Len’s sat phone and is no more than the push of a memory button away. The entire rescue services of North America would then be at our disposal, down to a huge, twin-rotor helicopter that can navigate through fog and find us by Global Positioning Coordinates (p. 38).

For Kerasote (2004), this digital security blanket is not all that welcome: “The mixture of genuine fear at being alone in the vastness of the high latitudes, and the lovely tension of facing that fear with no resources other than what we’ve brought along, and the wit inspired by necessity is diminished” (p. 38). It’s already been over a decade since Kerasote’s expedition, and the wilderness-shrinking technology has not rested in the meantime.

More recently, a wilderness professor named Dan Dustin took a long walk – some 750 miles – along the southern end of the Pacific Crest Trail, parts of which are nearly as wild and remote as any you can find in the continental United States. And yet, Dustin was struck by the fact that most his fellow trail walkers carried devices that not only distracted them from the immediate environment they presumably were there to enjoy and contemplate, but also wrapped them in a nice cozy blanket of electronic security (see Dustin, Beck, and Rose 2017). GPS apps on their phones provided detailed information about what lay ahead, where to camp, where to get water, and what to look at. To Dustin at least, the adventure of the unknown seemed to be replaced by a sort of smug sense of domination through information.

Conclusion

Without books like Hunter’s and Downes’s, it would be awfully easy for us to forget two of the major reasons for wilderness protection. One is to save an ancient experience in which one is far removed from the modern-day world and deeply immersed in a much wilder one. The other is so that at least a few cultures, who until very recently were deeply connected to wildness, might maintain their traditions against enormous threats to them from powerful financial forces driven mainly by profit incentives.

As pointed out by Kerasote and Dustin (and many others), we live today in a culture infatuated with electronic technology and obsessed with feats of fast transit. So maybe intrusions such as air taxis and satellite communications are a reasonable price to pay for a few places left roadless, unlogged, and unmined. And at least the air transportation, by enabling more people to see more wilderness areas, may help maintain political support for them. But we ought to do as much as possible to help wilderness users more fully disconnect from the many distractions of the modern world. I hope, for instance, that educational programs continue to emphasize the ancient skills of astronomical or compass navigation. I hope some are having their students make their own maps of the country they travel in, as Hunter and Downes did. I hope Boy and Girl Scouts, Outward Bound and NOLS programs, and the like, continue to highly discourage – or even better, ban completely — electronic gadgets in their programs. And I hope at least some agencies can continue to allow, if not encourage, the adventure of off-trail travel across their lands.

In closing, let’s give P. G. Downes, the school teacher turned avid Canadian wilderness explorer, the last word. Downes worked hard to find the kind of wildness he seems to have needed. Today, people are still out there conducting the same search. I like to think it’ still possible for today’s adventurers to have an insight like Downes did one day in the North. He was, as he recalled, “camping on the edge of tree line, one of those indescribable smoky, bright-hazy days one sometimes gets in the high latitudes.” It had been a very trying trip, even disappointing in some ways. But then this occurred to him: “I had seen a lot of it just as the old north was vanishing; the north of no time, of game, of Indians, Eskimos, of unlimited space and freedom.… And I said to myself: Well, I suppose I shall never be so happy again” (2011, para. 18; p. xv).

JAMES M. GLOVER taught wilderness-related classes at Southern Illinois University (retired), is a frequent contributor to IJW, and is a biographer of wilderness visionaries. His biography Bob Marshall, A Wilderness Original has been reprinted and is available at The Mountaineers Books; email: jimglover97@gmail.com

References

Downes, P. G. 2011. Sleeping Island: The Narrative of a Summer’s Travel in Northern Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. Ottawa, ON: McGahern Stewart Publishing.

Dustin, D., L. Beck, and J. Rose. 2017. Landscape to techscape: Metamorphosis along the Pacific Crest Trail.

International Journal of Wilderness 23(1): 25–30.

Hunter, F. 2015. That Summer on the Nahanni 1928: The Journals of Fenley Hunter. Frances Lake and a Trip to the Western Arctic. Ottawa, ON: McGahern Stewart Publishing.

Kerasote, T. 2004. Out There: In the Wild in a Wired Age. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press.

Nueltin Lake Provincial Park Management Plan, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.gov.mb.ca/sd/parks/pdf/nueltin_lake_mp.pdf.

Read Next

WILD11: Why China, and Why Now

The 11th World Wilderness Congress (WWC), or WILD11, will convene in China in late 2019. Our China partners have promised exact venue and date for 2019 in September of this year.

Understanding and Mitigating Wilderness Therapy Impacts: The Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Case Study

Studies demonstrate that wilderness therapy programs can be beneficial for participants; however, little research has explored the ecological impacts of these programs.

Visitor Experiences of Wilderness Soundscapes in Denali National Park and Preserve

Denali National Park and Preserve (DNPP), home to 6 million acres (2,428,114 ha) of land protected as wilderness, has collected a variety of biophysical acoustic data related to a backcountry management plan.