© Staffan Widstrand / Wild Wonders of China

A Preliminary Study on Mapping Wilderness in Mainland China

International Perspectives

August 2018 | Volume 24, Number 2

PEER REVIEWED

EDITOR’S NOTE: The original article was published in June 2017 in Chinese Landscape Architecture (《中国园林》国园林国园林》) (Cao, Y., Long, Y., Yang, R., 2017. Research on the identification and spatial distribution of wilderness areas at the national scale in Mainland China [J]. Chinese Landscape Architecture, 6: 26–33.). Invited by IJW, authorized by the authors, and permitted by CLA, this article appears as a translated summary of the original version.

Wilderness areas are, in the main, places that are ecologically intact, mostly free of industrial infrastructure, and without significant human interference. With a growing appreciation of the intrinsic value of wilderness, more attention is being paid to wilderness protection and management especially as threats increase and remaining wilderness areas shrink in size (Casson et al. 2016).

Practical experience in many countries has shown that maps depicting the spatial distribution of wilderness provide baseline information for the development and implementation of wilderness protection policies. Accurate and reliable wilderness inventories are an essential basis for robust designation of wilderness protected areas and the development of associated management policies.

Due to the lack of a wilderness inventory in China, the total area and the spatial distribution of wilderness are neither known nor fully understood. This places considerable restrictions on wilderness protection. This article therefore focuses on identifying and understanding the spatial distribution of wilderness in mainland China to provide a practical basis for the future development of Chinese wilderness protection policies (Cao et al. 2017).

The Concept of Wilderness Mapping

Different people often have different opinions on “how wild should wilderness be?” which makes the concept of wilderness a complex one to implement. How to apply multiple and complex wilderness definitions into a meaningful wilderness map is the first question that needs to be answered.

The idea of defining the point at which wilderness begins and ends along the environmental modification spectrum was first proposed by Roderick Nash in his book Wilderness and the American Mind (Nash 2016). His approach was to emphasize the variations of intensity of human impact on landscapes and so define the wilderness continuum. This was further developed by Lesslie and Taylor and applied to wilderness mapping in the early 1980s (Lesslie and Taylor 1985). The wilderness continuum emphasizes the transition from urban areas to pristine nature through varying levels of human modification as reflected in the intensity of human impacts on landscape. The basic attributes of the wilderness include measures of remoteness and naturalness such that wilderness quality increases with the increased remoteness and naturalness. In this manner, wilderness quality can be divided into high, relatively high, medium, and low levels. Defining wilderness by these relativistic ideas helps us to understand the concept of wilderness from a spatial perspective.

Based on this concept of the wilderness continuum, GIS-based wilderness quality mapping is the most commonly applied method of identifying the spatial extent and quality of wilderness areas. Although the first global mapping was carried out using manual techniques (McCloskey and Spalding 1989), wilderness mapping at various spatial scales developed rapidly with the development of satellite technology and GIS from the 1980s onward. During the past 30 years, several wilderness mapping projects have been carried out at global scale (Sanderson et al. 2002; See et al. 2016), continental scale (Fisher et al. 2010; Carver 2010), and in countries, regions, and individual protected areas (Kliskey and Kearsley 1993; Carver et al. 2013; Orsi et al. 2013; Măntoiu et al. 2016; Lin et al. 2016).

Several countries have conducted wilderness mapping studies including Australia (Lesslie and Maslen 1995), the United States (Aplet et al. 2010), the United Kingdom (Carver et al. 2002), Iceland (Ólafsdóttir et al. 2016), Denmark (Müller et al. 2015), and Austria (Plutzar et al. 2016), some of which have effectively supported wilderness protection policies. These currently provide inspiration and a technical lead for ongoing developments in China.

The Model of Wilderness Mapping for China

In developing a wilderness map for China, we address the principal questions: “Where are, how large, and of what “quality” are China’s remaining wilderness areas?” Our objective is to map the spatial distribution of the remaining wilderness areas in China, thereby providing a practical base for the further development of Chinese wilderness protection policies. The study area is mainland China excluding Taiwan and marine areas.

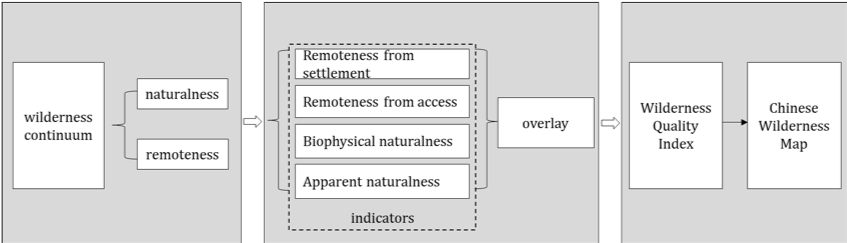

The mapping model is shown in Figure 1. Four indicators reflecting the wilderness qualities or attributes are selected and mapped as follows:

Remoteness from the settlements (i.e., areas of permanent human occupation)

Remoteness from vehicular access

Biophysical naturalness (i.e., the degree of biophysical disturbance by modern society)

Apparent naturalness (the degree of involvement of modern artificial facilities)

These four indicators reflect two aspects of the wilderness definition simultaneously: on one hand, from the “ecological” point of view, wilderness is natural areas with fewer human impacts and high naturalness; on the other hand, from the “perceptive” point of view, wilderness is seen as remote with almost no human-made facilities or habitation.

To map these indices, national datasets, including urban and rural construction land, road networks, land use, and artificial facilities, were selected and mapped using GIS methods according to the four indicators described above. The results of each individual indicators are overlaid with equal weights using a simple weighted linear summation Multi-Criteria Evaluation (MCE) approach to obtain the map of Chinese Wilderness Quality Index (WQI). This is then used to further identify wilderness areas with different values.

The resolution of the map is 1 km2 (.39 mile2). Each 1 km2 grid cell corresponds to a wilderness index ranging from 0 to 100. This resolution is deemed sufficient for mapping wilderness at the national scale in China.

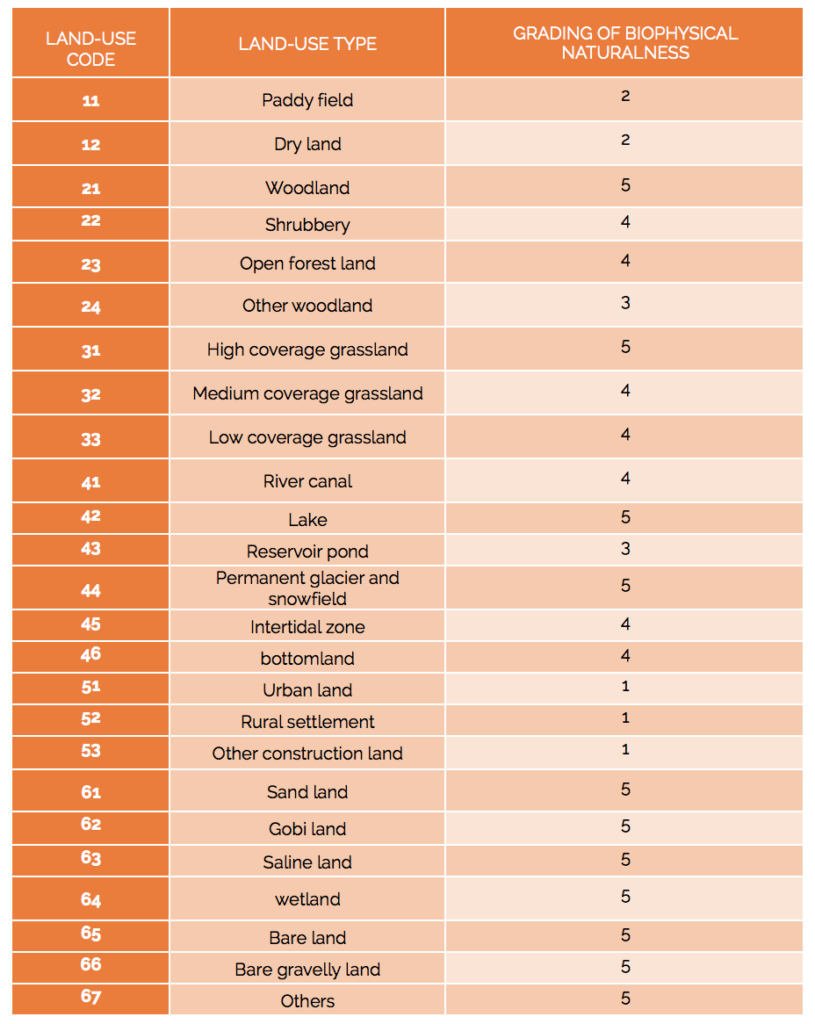

Table 1 – The grading evaluation table of different land-use types corresponding to the natural degree

Mapping Wilderness Attributes

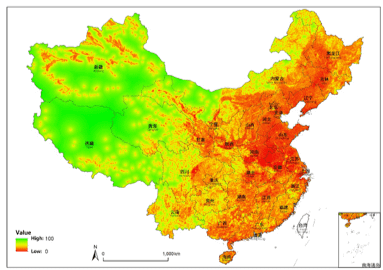

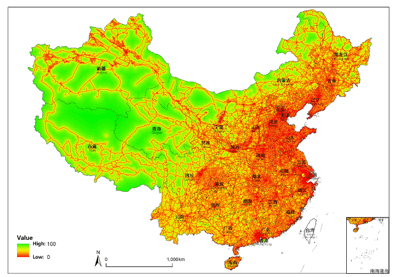

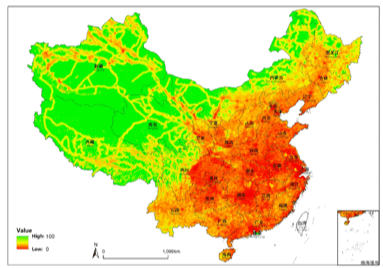

Remoteness from settlement reflects the distance to/from existing urban and rural habitation. Data on urban and rural construction land in China (Liu et al. 2014) are used as the source to calculate remoteness as Euclidean distances (see Figure 2). Remoteness from access reflects the distance from roads. “Roadless areas” are usually considered to be an important indicator of wilderness (Selva et al. 2011). Chinese traffic network data, including railways, highways, national roads, provincial roads and urban roads, are merged and used as inputs when calculating Euclidean distance from mechanized access (see Figure 3).

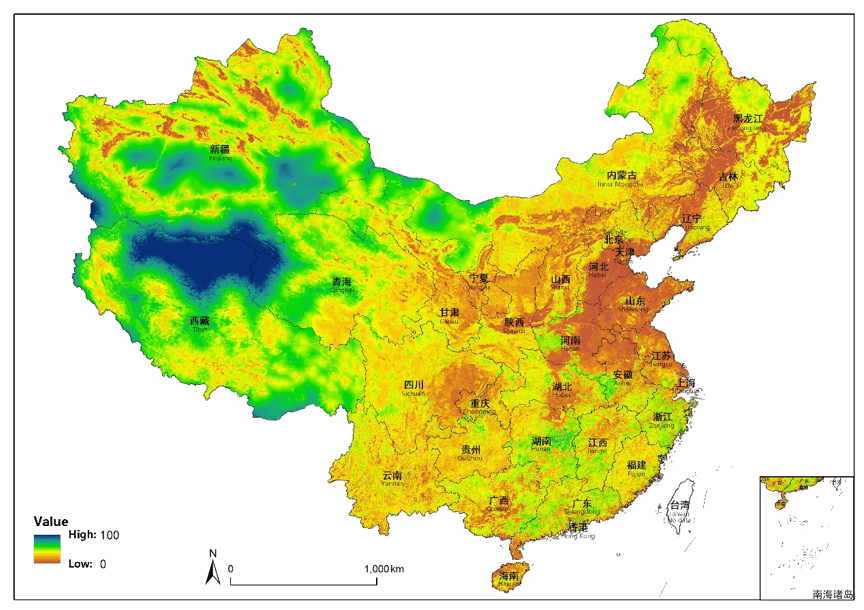

Biophysical naturalness reflects the degree of human modification of land cover based on a naturalness grading given to different types of land use. The 2010 national land-use data is selected as the base data (Liu et al. 2014), which itself is based on classified remote sensing images. There are six principal types of land use, including cultivated land, forestland, grassland, open water, residential land, and “unused” land, and 25 secondary types in this classification. The land-use types corresponding to the land code (land resource classification system) are reclassified to reflect the likely degree of human modification of natural ecosystems (See Table 1 and Figure 4).

Apparent naturalness reflects the extent to which an area is affected by permanent modern human artifacts. Distribution of traffic network data and settlement data are selected as the input data because transportation infrastructure and buildings are two main kinds of artificial infrastructure seen in the landscape. The former data also includes artificial infrastructures near the road such as bridges, dams, and power lines. A kernel density tool is used to calculate the density of artificial facilities, which in turn is used to reflect the degree of apparent naturalness (see Figure 5).

Results

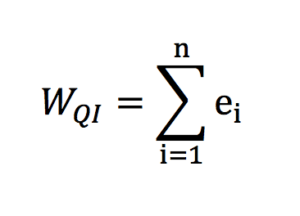

Since the calculation of the four indicators involves different dimensions and units, the first step in calculating a wilderness quality map is to normalize each of the input layers so that all the scores range from 0 to 100. To derive the Chinese Wilderness Index, scores of four indicators are combined by weighted linear summation within MCE. The formula is as follows.

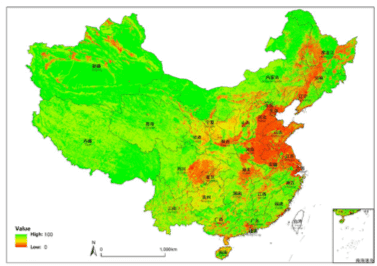

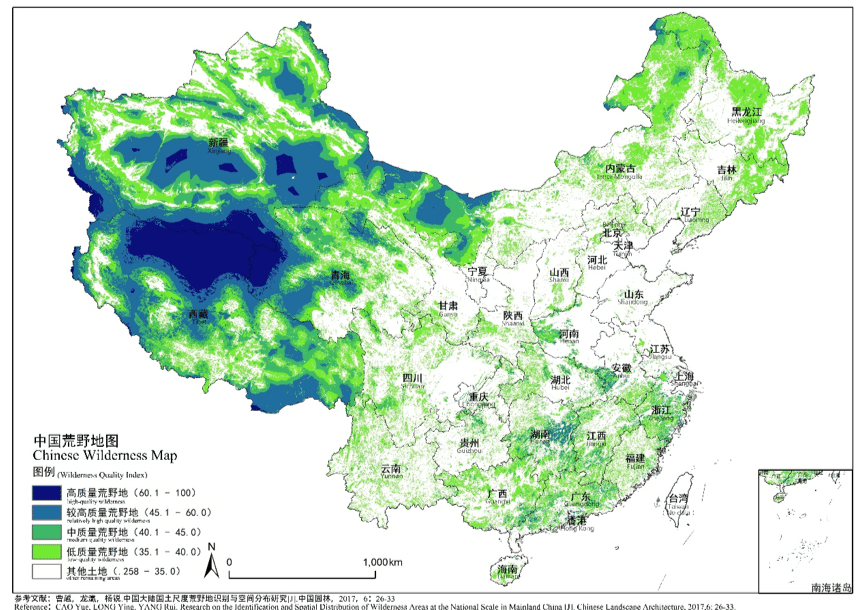

In this formula, WQI is the wilderness index, the value of which represents the wilderness quality; ei. is the standard score after evaluation of individual indicator; n is the number of indicators. It should be noted that equal weight of the four indicators is used for simplicity and clarity, but alternative weighting schemes could be explored in future. The resulting map of the Chinese Wilderness Quality Index (WQI) is shown in Figure 6.

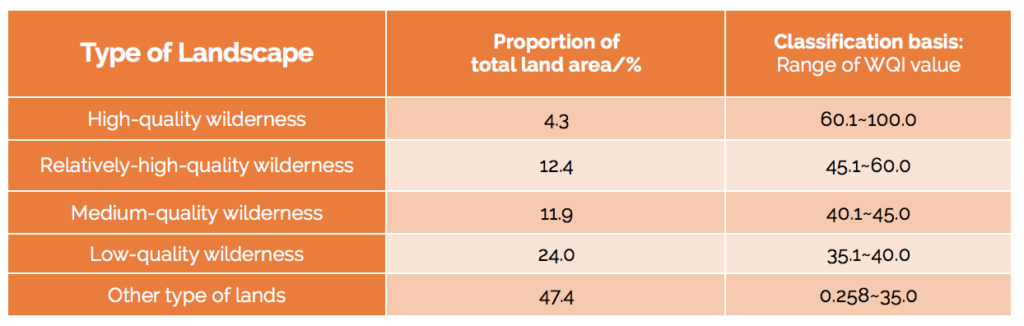

The wilderness quality index is then classified to divide all lands into five types: high-quality, relatively-high-quality, medium-quality, low-quality wilderness, and other type of lands (i.e., developed), as shown in Table 2. The spatial distribution of wilderness areas falling within the different levels are shown in the Chinese Wilderness Map (see Figure 7). Four types of wilderness take up to half of the whole land area, which together constitute those landscapes with the highest wilderness levels in mainland China.

High-quality wilderness accounts for 4.3% of the total land area of mainland China, mainly distributed in Qiangtang, the Altun Mountains, Hoh Xil, the Taklamakan Desert, and Lop Nur. Relatively-high-quality wilderness accounts for 12.4% of the total land area, mainly distributed in the northern Tibet Autonomous region, southern Xinjiang Autonomous region, Western Qinghai Province, and Western Inner Mongolia Autonomous region. Together these high-quality and relatively-high-quality wilderness areas are mainly distributed in Western China. Policies restricting land-use alterations, construction of artificial infrastructures, and human activities with negative effects on landscapes could be implemented in these regions to preserve their wilderness value and characteristics for future generations.

In addition, medium-quality wilderness accounts for 11.9% of the total land area, and low-quality wilderness accounts for 24.0%. This is distributed in provinces throughout western, central, and eastern China. Although the wilderness quality of these two types is lower, there are still high conservation values to be found in these lands, some of which have already been designated as protected areas, although many others have not. Wilderness areas in eastern and central China are highly fragmented, yet still provide important ecosystem services and recreational opportunities for nearby urban populations. These areas are perhaps more threatened than wilderness areas in western China and so perhaps need closer attention and further research due to the country’s large population and associated demand for economic development. Most importantly, the use of these areas should also be wisely and carefully managed to preserve their wilderness values to the extent possible.

Existing wild areas can be divided into two types: those that already have been designated as protected areas and those that have not. For those already included in protected area networks, the wilderness area and its values should be emphasized in the management zoning, and more scientific and sophisticated management policies should be developed to enhance conservation practices and the permanence of these wilderness zones. For wilderness areas not included in existing protected areas but with relatively-high-wilderness quality, the necessity and feasibility of further studies and practices should be explored. These include the designation of new protected wilderness areas and the delineation of ecological “red lines”1 around biodiversity hotspots to bridge the gap between existing protected areas and wilderness. The establishment of ecological networks connecting wilderness areas will be necessary, especially to maintain and enhance the ecological integrity of smaller wild areas. Rewilding might be necessary to either restore and enhance existing wilderness areas or improve connectivity between protected areas.

Conclusion and Discussion

This research has identified existing wilderness areas in China from a spatial perspective and created the first national-scale wilderness map in mainland China. Four levels of wilderness areas and other (developed) lands respectively accounted for 4.3%, 12.4%, 11.9%, 24.0%, and 47.4% of the total land area in mainland China. This study is meaningful in terms of both cognitive and practical aspects of wilderness protection in China. At the cognitive level, a new understanding of the national-scale landscape is added from the perspective of wilderness, which is a basic requirement for the further analysis of spatial patterns of wilderness at multiple spatial scales. At the practical level, it is expected to guide policy making about wilderness preservation and planning for a national Chinese Wilderness Preservation System. This will provide an essential reference for development and planning of various protected areas and for the delineation of ecological protection “red lines.”

This research develops the national-scale wilderness mapping in mainland China and lays the foundations for further work including

1. Improvements to the mapping work described here to better analyze spatial pat terns of wilderness in China, making use of big data and multisourced data.

2. Systematic assessment of the multiple values of wilderness in China, especially the biodiversity and ecosystem service values of wilderness areas.

3. Analysis of the conservation status of wilderness areas in China and identification of gaps in wilderness preservation to support proposals for more targeted wilderness preservation policies.

4. Multiscale wilderness mapping to directly assist management of wilderness protected areas, designation of new wilderness areas, management zoning, and wilderness recreation planning.

In recognition of the importance and sensitivity of wilderness areas, preservation of wilderness qualities and values should be discussed in the context of the Chinese national park pilot program and ongoing reconstruction of the country’s protected areas system. Wilderness preservation and management in China could be greatly improved by policies such as ecological function zoning, national main functional area planning, delineation of biodiversity conservation priority regions, and delineation of ecological “red lines” so as to maintain harmonious landscapes between humans and nature and leave precious “Wild China” for both contemporary and future generations.

Rejoinder

This article is a preliminary study focusing on wilderness mapping at a national scale. It creates the first wilderness map for China and could be taken as a starting point for further studies including regional- and park-focused mappings. The following issues should be addressed carefully in further studies.

Wilderness Definition and Attributes

The wilderness concept has been introduced and discussed in China from multiple perspectives, including environmental philosophy, environmental aesthetics, environmental history and nature writing. Scholars including HOU Wenhui (侯文蕙), CHENG Hong (程虹), LU Feng (卢风), YE Ping (叶平), and CHEN Wangheng (陈望衡) have made great contribution to this process. The special issue on wilderness in Chinese Landscape Architecture in 2017 raised more discussions on the wilderness concept in China (Carver 2017; Cao and Yang 2017; Martin 2017; Watson and Carver 2017). In addition, scholars have also started to explore the wilderness concept in the Chinese mind from the perspective of perception and philosophy, prompting the discussion to go a step further (Tin and Yang 2016; Tin et al. 2016; Gao 2017).

However, there is no unified or official definition of wilderness in China at present, so we have taken the IUCN and other existing definitions as a reference. We believe that defining wilderness in the Chinese context is extremely important; however, we cannot give a precise Chinese definition at this stage. In this case, our mapping work is based on the wilderness continuum and internationally recognized attributes that most wilderness mapping studies to date have adopted.

China is a huge and geographically/culturally varied country making it hard to find an approach that works at all scales. We think using naturalness and remoteness as wilderness attributes at the national scale is appropriate but acknowledge that these may need modifying to take social, cultural, political, and historical factors into account at the local scale.

Remoteness is a good indicator at the national scale, because where there are no roads it is more remote from human influence and therefore more likely to be wild/natural. However, at local scales more indicators should be taken into consideration including solitude, lack of visible human artifacts, population density, and terrain roughness, and more complex models should be used to map these variables including visibility, walking time, and so forth.

“Apparent naturalness” in this paper refers to the absence of certain artificial infrastructure –usually considered to be an important indicator of wilderness (Lesslie and Maslen 1995; Carver et al. 2002; Plutzar et al. 2016).

In Chinese, wilderness attribute (属性) has a similar meaning to wilderness indicator (指标)(指标)including naturalness, wildness, and remoteness. Wilderness Quality Index is a term used in European wilderness mapping projects. This may cause confusion because quality (质量) in Chinese usually relates to both good or bad qualities. Although WQI is understandable, using ( 荒野等级 / 荒野度 / 荒野程度 ) 荒野等级(wilderness levels/grades)) may be better as the classification of areas with different wilderness quality index.

Revisiting the Cultural Relevance of Wilderness in China and How to Acknowledge It in the Mapping Procedure

We acknowledge that simply transposing Western methods onto China may cause confusion in a cultural context. Further studies to address this problem may include the following points:

1. Conduct a series of wilderness perception surveys in China to see how this Western term is interpreted in the minds of Chinese people. This research may include different levels of public participation and expert consultation to address the following questions: Is wilderness a meaningful and useful concept in nature conservation in China?? What are the attributes that best define an area as wilderness in China? Which attributes are most important to the Chinese people?

2. Use MCE techniques to combine the indicators in different ways, orders, and sets with variable weights that acknowledge the cultural understanding and local, regional, national, and international differences.

3. The classification criteria of wilderness quality should be further improved using statistical and fuzzy methods to better interpret the resulting wilderness map in a culturally relevant way.

Comments on Data Quality

There are some problems in terms of data quality in this research that need to be recognized when considering the results. These include the following:

1. Due to data or calculation methods, there may be overestimation or underestimation of the wilderness quality, which should be verified and improved in regional-scale mapping work.

2. Overestimation of wilderness quality may exist in Chinese border regions due to edge effects arising from the absence of relevant data from neighboring countries.

3. Internal edge effects can also be seen due to variations in mapping standards between different provinces requiring careful calibration and checking using supplementary data.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vance G. Martin (president, the WILD Foundation and Wilderness Foundation Global, and chair, Wilderness Specialist Group [IUCN/WCPA]) for his guidance and advice; Li Jiajia for her assistance with data processing; and Peng Qinyi for his assistance with the translation of the paper.

CAO YUE is a PhD candidate in Department of Landscape Architecture at Tsinghua University. His research focuses on national park and protected areas, focusing especially on Chinese wilderness protection and the establishment of the Chinese Wilderness Preservation System; email: caoyue14@mails.tsinghua.edu.cn

YANG RUI is both chair of and professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture at Tsinghua University. He is a Chinese senior advisor to the WILD11 process; email: yrui@mail.tsinghua.edu.cn

LONG YING, PhD, is an associate professor in the School of Architecture, Tsinghua University. His research focuses on urban planning, quantitative urban studies, and applied urban modeling; email: ylong@tsinghua.edu.cn

STEVE CARVER is a geographer and senior lecturer at the University of Leeds. He has more than 25 years’ experience in the field of GIS and multicriteria evaluation with special interests in wild land, rewilding, landscape evaluation, and public participation; email: s.j.carver@leeds.ac.uk

References

Aplet, G., J. Thomson, and M. Wilbert. 2000. Indicators of wildness: Using attributes of the land to assess the context of wilderness. In Proceedings: Wilderness Science in a Time of Change – Volume 2: Wilderness withing context of largers systems, ed. S. F. McCool, D. N. Cole, W. T. Borrie, and J. O’Laughlin (pp. 89–98). Proceedings RMRS-P-15-VOL-2. Ogden, UT: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Reseach Station.

Cao, Y., and R. Yang. 2017. The research framework and key issues of Chinese wilderness studies. Chinese Landscape Architecture 6: 10–15. [in Chinese]

Cao, Y., Y. Long, and R. Yang. 2017. Research on the identification and spatial distribution of wilderness areas at the national scale in mainland China [J]. Chinese Landscape Architecture 6: 26–33. [in Chinese]

Carver, S. 2010. Mountains and wilderness. European Environment Agency (2010) Europe’s Ecological Backbone: Recognising the True Value of Our Mountains (pp.192–201). Copenhagen: European Environment Agency .

———. 2017. Lessons from the West: Developing wilderness mapping techniques and their potential in China and SE Asia. Chinese Landscape Architecture 6: 20–25. [in Chinese, translated by Cao, Y.]

Carver, S., A. J. Evans, and S. Fritz. 2002. Wilderness attribute mapping in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Wilderness 8(1): 24–29.

Carver, S., J. Tricker, and P. Landres. 2013. Keeping it wild: Mapping wilderness character in the United States. Journal of Environmental Management 131: 239–255.

Casson, S. A., V. G. Martin, A. Watson, A. Stringer, and C. F. Kormos. 2016. Wilderness protected areas: Management guidelines for IUCN Category 1b protected areas. IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA). Monograph series no: 25. 92p

Fisher, M., S. Carver, Z. Kun, R. McMorran, K. Arrell, and G. Mitchell. 2010. Review of Status and Conservation of Wild Land in Europe. Report: The Wildland Research Institute. University of Leeds: UK, 148, p. 131.

Gao, S., 2017. Can Chinese Philosophy Embrace Wilderness? Environmental Ethics.

Kliskey, A. D., and G. W. Kearsley. 1993. Mapping multiple perceptions of wilderness in southern New Zealand. Applied Geography 13(3): 203–223.

Lesslie, R. G., and S. G. Taylor. 1985. The wilderness continuum concept and its implications for Australian wilderness preservation policy. Biological Conservation 32(4): 309–333.

Lesslie, R., and M. Maslen. 1995. National Wilderness Inventory Handbook of Procedures: Content and Usage Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth Government Printer.

Lin, S., R. Wu, C. Hua, J. Ma, W. Wang, F. Yang, and J. Wang. 2016. Identifying local-scale wilderness for on-ground conservation actions within a global biodiversity hotspot. Scientific Reports 6: 25898.

Liu, J., W. Kuang, Z. Zhang, X. Xu, Y. Qin, J. Ning, W. Zhou, S. Zhang, R. Li, C. Yan, and S. Wu. 2014. Spatiotemporal characteristics, patterns, and causes of land-use changes in China since the late 1980s. Journal of Geographical Sciences 24(2): 195–210. [in Chinese]

Măntoiu, D. Ş., M. C. Nistorescu, I. C. Şandric, I. C. Mirea, A. Hăgătiş, and E. Stanciu. 2016. Wilderness Areas in Romania: A Case Study on the South Western Carpathians. In Mapping Wilderness (pp. 145–156). Dordrecht: Springer.

Martin, V. G. 2017. Wilderness – international perspectives and the China opportunity. Chinese Landscape Architecture 6: 5–9. [in Chinese, translated by Zhang, Q.]

McCloskey, J. M., and H. Spalding. 1989. A reconnaissance-level inventory of the amount of wilderness remaining in the world. Ambio 221–227.

Müller, A., P. K. Bøcher, and J. C. Svenning, 2015. Where are the wilder parts of anthropogenic landscapes? A mapping case study for Denmark. Landscape and Urban Planning 144: 90–102.

Nash, R. 2016. Wilderness and the American Mind. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Ólafsdóttir, R., A. D. Sæþórsdóttir, and M. Runnström. 2016. Purism scale approach for wilderness mapping in Iceland. In Mapping Wilderness (pp. 157–176). Springer, Dordrecht.

Orsi, F., D. Geneletti, and A. Borsdorf. 2013. Mapping wildness for protected area management: A methodological approach and application to the Dolomites UNESCO World Heritage Site (Italy). Landscape and Urban Planning, 120: 1–15.

Plutzar, C., K. Enzenhofer, F. Hoser, M. Zika, and B. Kohler. 2016. Is there something wild in Austria? In Mapping Wilderness (pp. 177–189). Dordrecht: Springer.

Sanderson, E. W., M. Jaiteh, M. A. Levy, K. H. Redford, A. V. Wannebo, and G. Woolmer. 2002. The human footprint and the last of the wild. BioScience 52(10): 891–904.

See, L., S. Fritz, C. Perger, C. Schill, F. Albrecht, I. McCallum, D. Schepaschenko, M. Van der Velde, F. Kraxner, U. D. Baruah, and A. Saikia. 2016. Mapping human impact using crowdsourcing. In Mapping Wilderness (pp. 89–101). Dordrecht: Springer.

Selva, N., S. Kreft, V. Kati, M. Schluck, B. G. Jonsson, B. Mihok, H. Okarma, and P. L. Ibisch. 2011. Roadless and low-traffic areas as conservation targets in Europe. Environmental Management 48(5): 865.

Tin, T., R. Summerson, and H. R. Yang. 2016. Wilderness or pure land: Tourists’ perceptions of Antarctica. The Polar Journal 6(2): 307–327.

Tin, T., and R. Yang. 2016. Tracing the contours of wilderness in the Chinese mind. International Journal of Wilderness 22(2): 35–40.

Watson, A. E., and S. Carver. 2017. Wilderness, rewilding and free-willed ecosystems: Evolving concepts in stewardship of IUCN protected category 1b areas. Chinese Landscape Architecture 6: 34–38. [in Chinese, translated by Huang, C. and Yang, H.]

Read Next

WILD11: Why China, and Why Now

The 11th World Wilderness Congress (WWC), or WILD11, will convene in China in late 2019. Our China partners have promised exact venue and date for 2019 in September of this year.

Paradigms Lost: A Rumination on the Pursuit of Wildness

Recently, two reissued books from the early 1900s caught my attention. The books are That Summer on the Nahanni 1928: The Journals of Fenley Hunter and Sleeping Island: A Journey to the Edge of the Barrens, by P. G. Downes.

Understanding and Mitigating Wilderness Therapy Impacts: The Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Case Study

Studies demonstrate that wilderness therapy programs can be beneficial for participants; however, little research has explored the ecological impacts of these programs.