Soul of the Wilderness

December 2015 | Volume 231, Number 3

By STEWART BRANDBORG

In any reflection on my love for wilderness, it is the realization that whenever I find myself in wilderness, the prevailing influence that I sense so deeply is the wildness of the place. Whether in the alpine of my beloved Rocky Mountains, the Arizona deserts, coastal marshes, or beachscapes, I am deeply affected by the single fact that this place is, as it is, evolved through natural processes – in total wildness.Beyond the absence of human influence, it is only the natural processes or nature’s evolution that brings me what I am there to savor: the product of natural forces so immense in their dimension that I am humbled in trying to comprehend.

This quality of wildness, of autonomous and unfettered nature, was the central concern of those of us who, in the 1950s and early 1960s, wrote and worked for enactment of the Wilderness Act. My boss and mentor at the Wilderness Society, Howard Zahniser, chose untrammeled as the key word in the Act’s definition of wilderness because it means free from man’s intent to alter, control, or manipulate nature and its processes. Olaus Murie called it “nature’s freedom.” Sig Olson, George Marshall, Harvey Broom, and Ernest Oberholtzer – all of us agreed with Zahniser that untrammeled was the best word to convey this most important quality of wilderness character. So those of us who had a hand in drafting the Wilderness Act or pushing it through Congress considered wildness to be the cornerstone of wilderness character, the preservation of which is the central mandate of the Act. As Zahniser said to the New York legislature in 1953, three years before he wrote the first draft of the Wilderness Bill, “We must remember always that the essential quality of the wilderness is its wildness.”

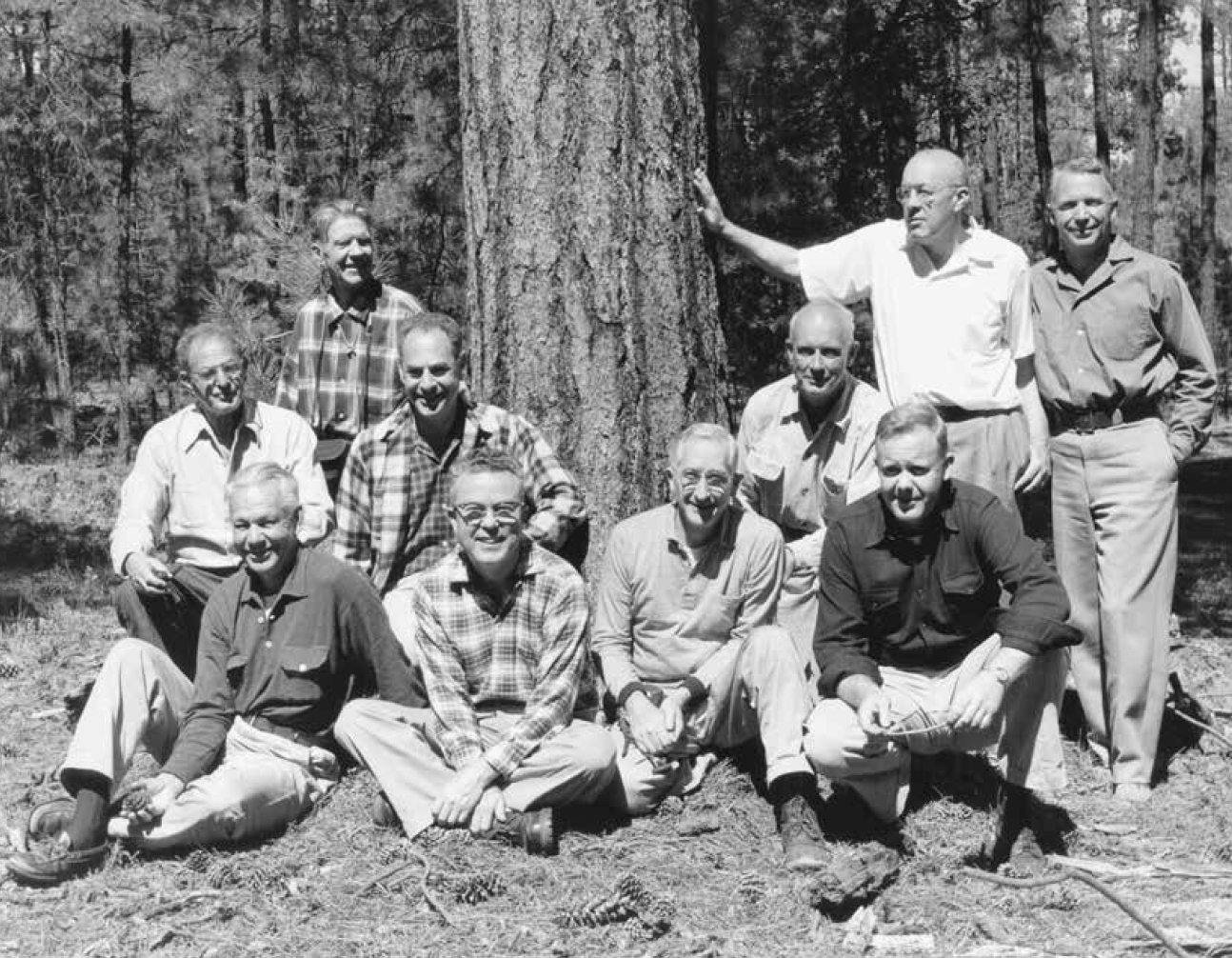

Figure 1 – Wilderness Society Governing Council meeting on September 2–5, 1962, held at the Elbo Ranch in Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. Back row, left to right: Olaus Murie, Howard Zahniser, Robert Cooney; middle row: Jim Marshall, George Marshall, Ernest Griffith; front row: Sigurd F. Olson, Dick Leonard, Harvey Broome, Stewart M. Brandborg. Photo courtesy of the Brandborg family.

So it makes me mad as hell to see that some in the agencies charged with implementing the Act have reduced wildness to just one of four or five qualities of wilderness. It has diminished the central importance of wildness in wilderness character to instead only a fraction of wilderness character. It has opened the door to manipulation of natural processes that strikes at the heart of wilderness character.

Now toward the end of my life’s work for wilderness, I ask its defenders to never forget: Wildness is foremost the quality of wilderness that we must seek to preserve. It is the forces of nature at full play in the absence of human intent, not to be categorized or classified in any structured form; animal and plant communities evolving with geological forces as they always have, perpetuating the wild in these enclaves we have set apart as wilderness.

Figure 2 – Brandborg giving a speech about wilderness at a podium ca. 1988. Photo courtesy of the Brandborg family.

Throughout our nation we have a diversity of wildland areas where we can still find the evolutionary processes of nature at full play, molding the environment as each fulfills its role: weather; climate change; evolutional, natural selection of plants and animals; the cataclysmic impacts of fire; and other natural forces.

Wilderness is recognized because of its wild qualities and naturalness free from human influences. In its wildness it is not to be categorized or submitted to human patterns of definition. Untrammeled nature at its fullest in the absence of human manipulation is its present and its future. We can only strive for its preservation in the absence of human contrived definition.

It is the wild that permeates the human experience in wilderness. We, as visitors, become aware that this wild place has survived through natural evolution and in its wildness it determines its own future – not subject to the subjective classifications of humankind, but in and of itself beyond classification.

Let us never forget that this is the essence of wilderness character.

STEWART BRANDBORG conducted pioneering wilderness field research on mountain goats in Idaho and Montana in the 1940s and 1950s before moving his family to the Washington, D.C., area to take a job with the National Wildlife Federation. He joined the Governing Council of the Wilderness Society in 1956 and began working with Howard Zahniser to craft and pass the Wilderness Act. In 1960, Zahniser hired Brandborg on the Wilderness Society staff to help push the Wilderness Act over the finish line. After Zahniser’s early death in 1964, Brandborg directed the Wilderness Society for the next dozen years, building a nationwide grassroots wilderness movement and bringing new areas into the National Wilderness Preservation System. He continues his wilderness advocacy today, including serving as senior advisor for Wilderness Watch.