Ibex in the French Alps. Photo by Adrien Stachowiak on Unsplash.

Wilderness Babel: On the Impossibility of Translating “Wilderness” into French

BY ALEXANDRA LOCQUET

International Perspectives

October 2024 | Volume 30, Number 2

Wilderness Babel is a project created by Marcus Hall, Wilko Graf Von Hardenberg, Tina Tin, and Robert Dvorak from the original online exhibit at the Environment and Society Portal of the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. It has been developed as an ongoing IJW series that discusses the terminology chosen to express wilderness as a concept in other languages or the nuances of this word in different English-speaking contexts. It discusses the adoption of the term “wilderness” in other cultural contexts – as well as other wilderness terms, from “outback” to “jungle,” and “bush” to “country.” And it explores how concepts of wilderness have found expression in visual representation in media of different sorts as well as in nonverbal communication.

The concept of wilderness has its origins in the English-speaking world and is associated with American culture (Arnould and Glon 2006). The notion of wilderness, although multidimensional and complex (Ceauşu et al. 2015), commonly refers to wild spaces where human influence is virtually nonexistent. Defining wilderness remains a complicated task because the notion is highly subjective and depends on individuals’ and communities’ perceptions of the living world and their perceptions of the relationships between the human and the other-than-human spheres (Kirchhoff and Vicenzotti 2014). In addition, the notion of wilderness is socially constructed, charged with symbolism (Meyer 2013), and highly influenced by the socio-cultural context. It was developed within first mystical and then philosophical contexts and the global environmental movement has used it to characterize and designate protected areas. Wilderness has thus become a central concept in nature conservation since the 19th century.

The French wilderness

The diversity of imaginaries associated with wilderness cannot be reduced to a common definition (Carver, Evans, and Fritz 2002; Jones-Walters and Čivić 2010). The notion of wilderness depends on different mental universes and has no direct equivalent in most languages outside the English-speaking world (Locquet 2021). It is difficult to transpose into other languages because of the complex and multiple dimensions that are involved (Ceauşu et al. 2015).

In French, “naturalité” has been used as a translation of “wilderness” (Lecomte 1999; Vallauri et al. 2010; Guetté et al. 2018). “Naturalité” refers to a natural or spontaneous state in opposition to what is anthropogenic; in other words, a functional, undisturbed ecosystem. It can be translated into English as “naturalness,” which characterizes a state of nature to which a certain quality (ecological or functional) is attributed (Woods 2017). However, according to some authors, naturalness is not an equivalent of wilderness; like wildness – a vital quality that is highly subjective and refers more to the sensation of nature than to a space that meets strict ecological criteria – naturalness can be considered a component of wilderness (Landres et al. 2000; Oelschlaeger 1991; Ridder 2007).

Other French expressions have been used as translations of “wilderness.” However, they are mainly translations of the dimensions of the “wild” and the absence of human interference and do not provide a satisfactory match with the notion of wilderness (Locquet and Héritier 2020). While “wilderness” is a noun that refers to something – an idea, a space – its French translations make use of adjectives as descriptors of nature. The most commonly used French translations of “wilderness” are “nature sauvage” (wild nature) and “nature vierge” (pristine, virgin nature) (Barthod 2010). In the official French translation of the European Parliament Resolution on Wilderness Areas in Europe (2009), However, insisting on the pristine nature of wilderness areas, particularly with a view to their application in the European context, is paradoxical. The long-standing role of human activity in modifying ecosystems and landscapes is widely recognized. This is why some authors prefer to use the term “féral” (feral), which is generally associated with animals or plants that have escaped domestication and returned to live in the wild. This concept was revived by Schnitzler and Génot (2012) as feral nature, to describe areas marked by the return of spontaneous processes following rural abandonment or the abandonment of human activities.

Initiatives Shaped by Semantics and Socio-ecosystems

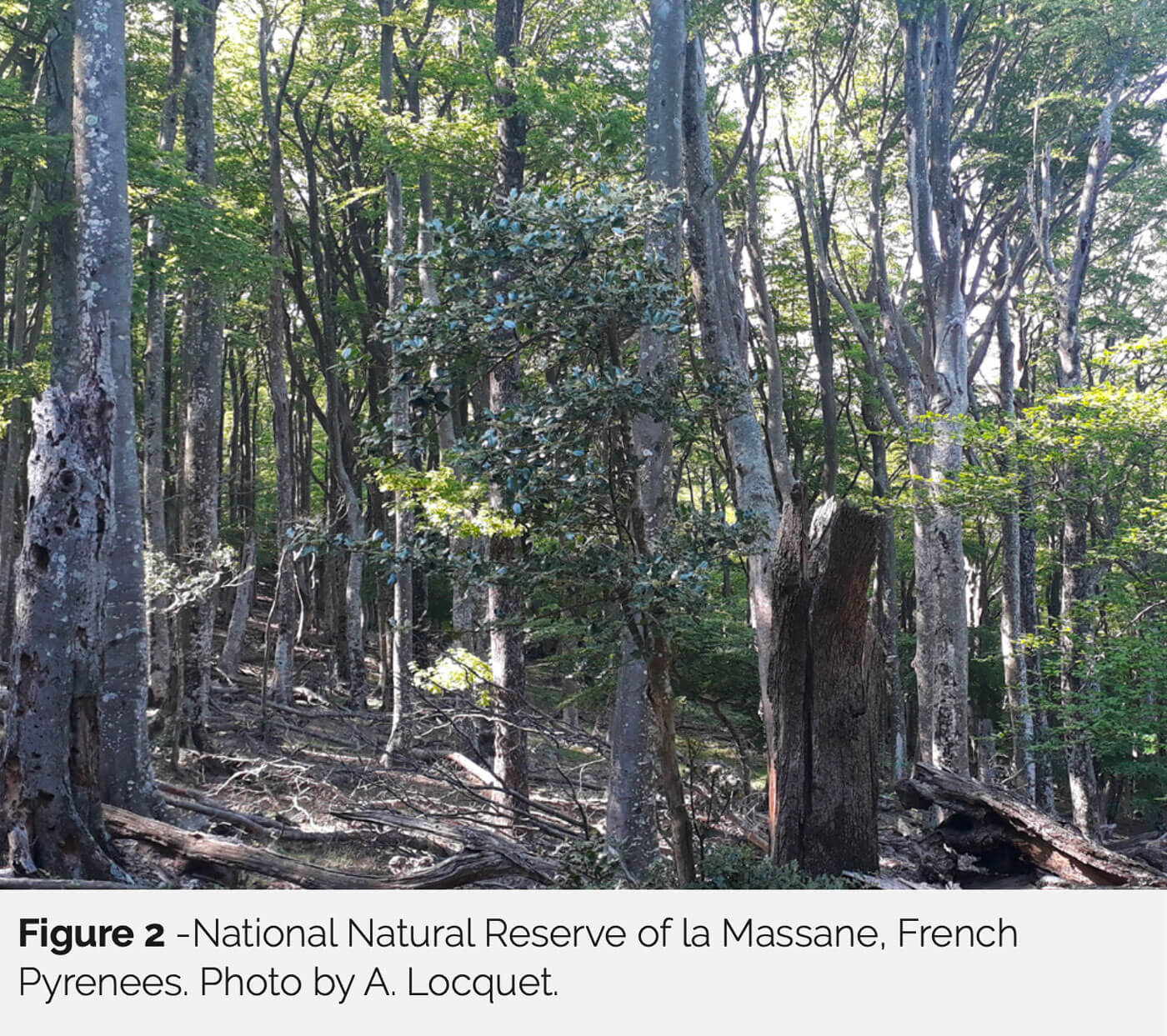

The difficulties involved in translating the wilderness concept into the European context, and in this case the French one, have contributed to the emergence of a variety of strategies in favor of wilderness in France. These approaches are based on the logic of recovering the wild characteristics of environments, with emphasis on ecosystem functionalities and the return of all the natural and spontaneous dynamics that are integral components of them. Strategies deployed in France vary from interventionist practices involving the introduction of animals (especially large herbivores), sometimes referred to as rewilding, to non-intervention management in which natural processes are free of any human intervention. These approaches are largely dependent on the socio-ecosystems in which they are implemented. For example, the concept of “libre évolution” (free evolution) emerged in the sphere of nature management in the 1990s and was reinforced in the 2000s due to the ecological restoration of forests and interest in the role of deadwood (Barraud 2021). Free evolution refers to the desire to let natural environments evolve spontaneously without human intervention, to “let nature take its course” (Génot 2020). Free evolution appears to be a criticism of interventionist management of nature that is based on the use of technical measures (Génot 2020; Deuffic, Brahic, and Dusacre 2022).

Like wilderness, the notion of free evolution is charged with ethical, political, and managerial dimensions. It invites us to rethink the value systems we attach to nature and the possibility of giving nature greater autonomy (Maris and Beau 2022). Free evolution also encourages us to question the relationship that our societies have with other-than-humans, at a time when the current environmental crisis is challenging our ability to coexist with all living things. In this way, “free evolution is not a candid letting go: it is a diplomatic practice” (Morizot 2020).

In line with the emergence of concerns about wilderness in France, a working group specifically dedicated to this subject was set up in 2012 with in the French Committee of the IUCN, under the guidance of the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA). This group brings together experts with a view to developing “both the conservation approaches to ‘wild’ (relict) nature and the dimension of rewilding areas” (Barthod and Lefebvre 2022).

Its work helps highlight the importance and implementation of free evolution in France, drawing attention to the numerous initiatives and discussions that have flourished across various nature conservation networks. The creation of this group was also a response to the need to identify wilderness in the French context, highlighting “the exception represented by what is implied (at least in Western Europe) behind wilderness” (Barthod and Lefebvre 2022). According to the group, acting in favor of wilderness in France necessarily implies the consideration of ecological, societal, and economic factors because of the country’s long history of human modification of the natural environment. As a result, the notion of wilderness in France does not seem to be in line with the American imaginary of great wild spaces but is rather more in line with rural or former rural spaces that have been profoundly modified by human activity. French wilderness is thus conceived and constructed in direct proximity and close interactions with society.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Tina Tin for her assistance with proofreading and translation.

ALEXANDRA LOCQUET is a geographer and researcher associated with the Ladyss laboratory (CNRS, France). She studies how wilderness is protected in France and Europe; email: locquetalex@gmail.com.

References

Barraud, R. 2021. (Re)Conquêtes sauvages : Trajectoires, spatialités et récits. HDR in Geography. Bordeaux Montaigne University.

Barthod, C., and T. Lefebvre. 2022. Le groupe de travail de l’UICN-France « Wilderness et nature férale ». Revue Forestière Française 73(2–3): 323–331.

Carver, S., A. J. Evans, and S. Fritz. 2002. Wilderness Attribute Mapping in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Wilderness 8(1): 24–29.

Ceauşu, S., S. Carver, P. H. Verburg, and H. U. Kuechly. 2015. European wilderness in time of farmland abandonment (pp. 25-46). In Rewilding European Landscapes, ed. H. M. Pereira and L. M. Navarro. SpringerOpens.

Deuffic, P., E. Brahic, and E. Dusacre. 2022. La naturalité à petit pas: Evolution des regards et des pratiques sur une notion émergente. Revue Forestière Française 73(2–3): 253–270.

European Parliament. 2009. European Parliament resolution of 3 February 2009 on Wilderness in Europe. (2008/2210[INI]).

Génot, J.-C. 2020. La Nature Malade de La Gestion. Hesse.

Guetté, A., J. Carruthers-Jones, L. Godet, and M. Robin. 2018. « Naturalité » Concepts and methods applied to nature conservation. CyberGeo 2018: 1–25. https://doi.org/10.4000/cybergeo.29140.

Jones-Walters, L., and K. Čivić. 2010. Wilderness and biodiversity. Journal of Nature Conservation 18: 338–339.

Kirchhoff, T., and V. Vicenzotti. 2014. A historical and systematic survey of European perceptions of wilderness. Environmental Values 23(4): 443–464.

Landres, P. B., M. W. Brunson, L. Merigliano, and S. Morton. 2000. Naturalness and wildness: The dilemma and irony of managing wilderness. In Wilderness Ecosystems, Threats and Management, 5: 377–381. Missoula, Montana.

Lecomte, J. 1999. Réflexions sur la naturalité. Le Courrier de l’environnement de l’INRA 37: 5–10.

Locquet, A. 2021. Born to be wild ? Représentations du sauvage et stratégies de protection de la wilderness en Europe. PhD diss., Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne University.

Locquet, A., and S. Héritier. 2020. Questioning nature and wildness in relation to the establishment of wilderness areas in Europe. CyberGeo.

Maris, V., and R. Beau. 2022. Le retour du sauvage – une question de nature et de temps. Revue Forestière Française 73(2–3): 281–292.

Meyer, T. 2013. Culture and cultural landscapes as functional matrices for wilderness and vice versa. European Journal of Environmental Sciences 3(2).

Morizot, B. 2020. Raviver les Braises du Vivant: Un Front Commun. Actes Sud Nature.

Oelschlaeger, M. 1991. The Idea of Wilderness: From Prehistory to the Age of Ecology. Royaume-Uni de Grande-Bretagne et d’Irlande du Nord.

Ridder, B. 2007. The naturalness versus wildness debate: Ambiguity, inconsistency, and unattainable objectivity. Restoration Ecology 15(1): 8–12.

Schnitzler, A., and J.-C. Génot. 2012. La France Des Friches : De La Ruralité à La Féralité. Quae.

Vallauri, D., J. André, J.-C. Génot, and R. Eynard-Machet. 2010. Biodiversité, Naturalité, Humanité Pour Inspirer La Gestion Des Forêts. Lavoisier.

Woods, M. 2017. Rethinking Wilderness. Broadview Press.

Read Next

Missing the Forest for the Algorithm

What is the value of wilderness? Well, what you have just completed reading is the “value of wilderness” as described by ChatGPT 3.5.

Rewilding Prerequisites: An Ecocentric Approach

Rewilding is increasingly gaining momentum as a conservation practice in Europe.

Trusting Tech and Wilderness in the 21st Century

A Response to Keeling’s The Trouble with Virtual Wilderness