Science & Research

December 2015 | Volume 231, Number 3

by RAMESH GHIMIRE, GARY T. GREEN, NEELAM C. POUDYAL, and H. KEN CORDELL

Abstract: While Americans in general perceive benefits from preserving wilderness areas, the perceived benefits may be different across subpopulation. To understand the underlying variations in perceived benefits across subpopulation, we employed a multivariate cluster analysis to data collected from a national survey regarding people’s evaluation of benefits from preserving wilderness areas, and analyzed sociodemographic characteristics, outdoor recreation choices, and support for land designation and wilderness protection across subpopulation. Findings suggested relatively younger people, college graduates, females, and nonconsumptive recreationists were more likely to perceive greater benefits from preserving wilderness areas compared to their counterparts. People who perceived greater benefits from preserving wilderness areas were more supportive of land designation and wilderness protection.

Keywords: Cluster Analysis, Outdoor Recreation, Perceived Benefits, Wilderness.

Introduction

The Wilderness Act (Public Law 88-577) was signed into law in 1965, creating the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS) to protect public wildlands in the United States. This massive wilderness system, which encompasses just over 110 million acres (44,515,420 ha), could not have been possible without congressional and public supports for land designation and wilderness protection (Ghimire et al. 2015).

In addition to providing opportunities for primitive experience, solitude, and unique outdoor recreation, wilderness areas provide various ecosystem service benefits, such as air and water purification, carbon sequestration, etc. Studies have shown that Americans perceive benefits from preserving wilderness areas and also want to preserve them for recreational, environmental, ecological, and economic reasons (Cordell et al. 2008; Ghimire et al. 2015; Bowker et al. 2014). Because of the differences in sociodemographic characteristics and other perception-related factors, people may perceive benefits from preserving wilderness areas distinctly. However, previous studies have tended to treat a diverse population as a homogenous unit and, hence, failed to reveal underlying variations in the perceived benefits across subpopulation. Understanding the public’s perception of wilderness benefits across subpopulation is important to help understand how the future of land designation and wilderness protection will be in the United States, given the expected changes in demographic structure in the future. This study analyzes how the American public with different demographic characteristics and outdoor recreation choices perceive benefits from preserving wilderness areas, and their views on land designation and wilderness protection.

Data and Method

Data for this study came from the National Survey on Recreation and the Environment (NSRE) conducted in 2008 (NSRE 2008). The NSRE is an ongoing series of surveys that began in 1960 as the National Recreation Survey and then eventually became the NSRE. The NSRE is a general population, random-digit-dialed telephone survey of individuals who are at least 16 years old, living in a U.S. household. The survey gathers information on a number of outdoor recreation and environmental topics, household structure, lifestyles, and demographics. Each version of the NSRE consists of different modules or sets of questions and surveys approximately 5,000 people. The data are weighted using post-stratification procedures to adjust for nonresponse according to age, race, gender, education, and rural/urban strata (Cordell et al. 2004).

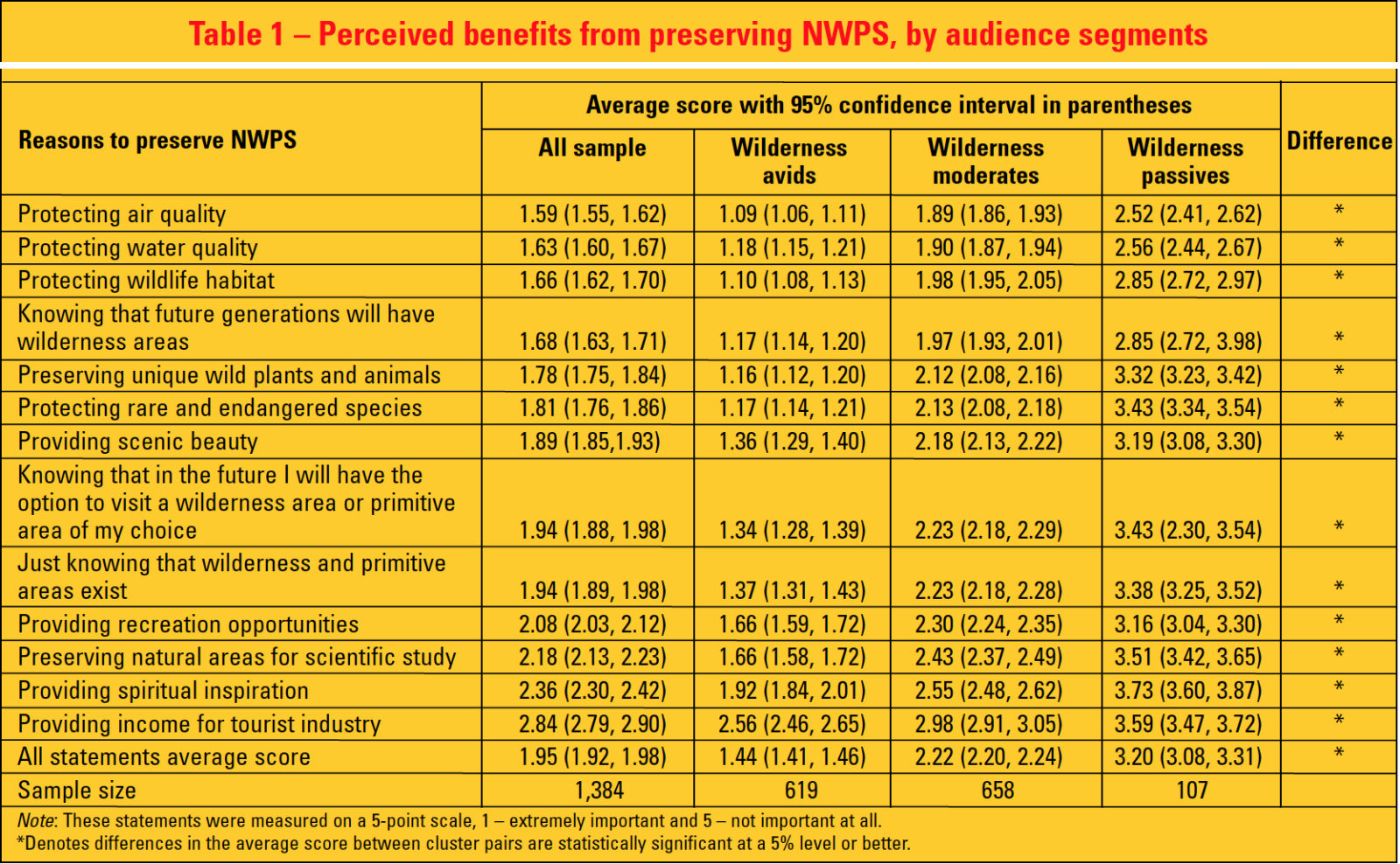

A subsample of approximately 1,500 respondents was presented with a set of 13 statements measuring their perception of benefits from preserving wilderness areas, and they were asked about their views on land designation and wilderness protection (see Table 1 for the list of statements used in the survey). To introduce the wilderness module in the survey, the following statement was used:

Wilderness areas provide a variety of benefits for different people. For each benefit I read, please tell me whether it is extremely important (=1), very important (=2), moderately important (=3), slightly important (=4) or not important at all (=5) to you as a reason to preserve wilderness areas.

The ordinal scale, used here, was also used in previous studies and refers to those benefits of preserving wilderness areas that people perceived as important (e.g., Cordell et al. 2008; Ghimire et al. 2015).

To segment the respondents, a K-means cluster analysis using Euclidian distancing was conducted on the series of 13 statements. Cluster analysis is a multivariate statistical technique to group a set of data in such a way that data in the same group (called a cluster) are more similar to each other than to those in other groups (clusters). A K-mean cluster analysis was preferred because it allows selecting the number of clusters to be used for analysis (Everitt et al. 2011).

Results and Discussions

The cluster analysis identified three unique groups of respondents (clusters) that perceived benefits from preserving wilderness areas (Table 1). One cluster called the wilderness avids represented those who perceived substantial benefits from preserving wilderness (average score = 1.44). In constrast, another cluster called the wilderness passives represented respondents who perceived lower benefits from preserving wilderness (average score = 3.20). Between these two clusters were the wilderness moderates, who perceived some benefits from preserving wilderness areas (average score = 2.22). The average score for each statement differed significantly between each cluster.

Respondent Demographics

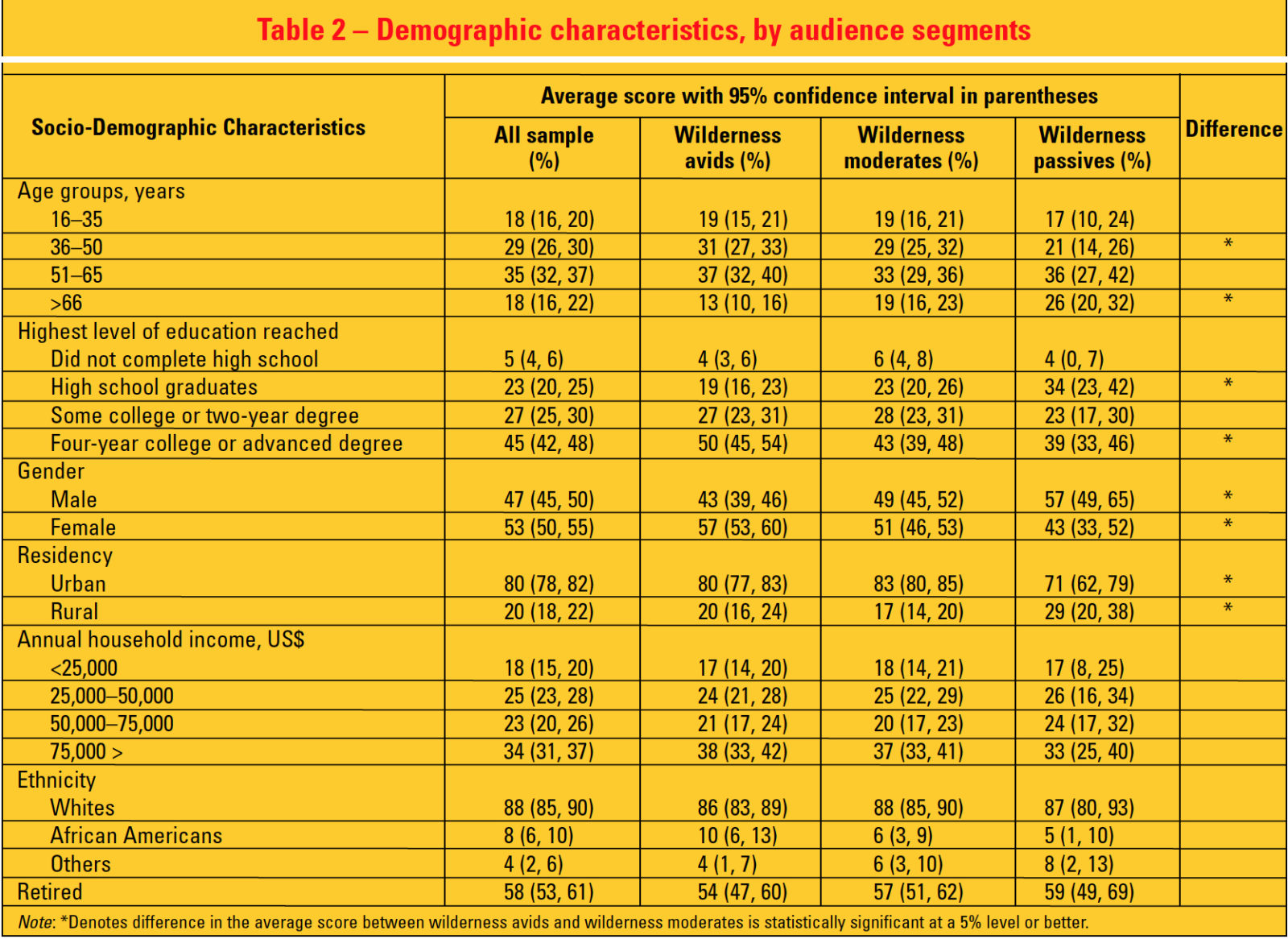

Respondents’ demographics differed across clusters (Table 2). In the cluster of wilderness avids, 31% of respondents belonged to the 36–50 years age group, and 13% of respondents belonged to the >66 years age group. In contrast, in the cluster of wilderness passives, 21% of respondents belonged to the 36–50 years group, and 26% of respondents belonged to the >66 years age group. Hence, relatively younger people were more likely to be wilderness avids, while relatively older people were more likely to be wilderness passives. In the cluster of wilderness avids, 19% of respondents were high school graduates, and 50% of respondents had a four-year college or advanced degree. In contrast, in the cluster of wilderness passives, 34% of respondents were high school graduates, and 39% of respondents had a four-year college or advanced degree. Hence, people with a college or advanced degree were more likely to be found in the wilderness avids cluster, while people with a high school degree were more likely to be in the wilderness passives cluster.

The perceived benefits from preserving wilderness areas differed, based on gender. In the cluster of wilderness avids, 57% of respondents were female and 43% of respondents were male, while 43% of respondents were female and 57% of respondents were male in the cluster of wilderness passives. Hence, females were more likely to be wilderness avids, and males were more likely to be wilderness passives.

Respondents did not differ significantly on income, ethnicity, and employment status. However, a relatively large percentage of respondents (38%) in the cluster of wilderness avids had an annual income greater than $75,000/year, while only 33% of wilderness passives had this same income level. Because of the U.S. demographics, these three clusters were dominated by whites. However, there were twice as many African Americans (10%) in the cluster of wilderness avids compared to the cluster of wilderness passives (5%), and twice as many other ethnic groups in the cluster of wilderness passives (8%) compared to the cluster of wilderness avids (4%). While 54% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness avids and 57% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness moderates were retired, 59% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness passives were retired.

Outdoor Recreation Choices

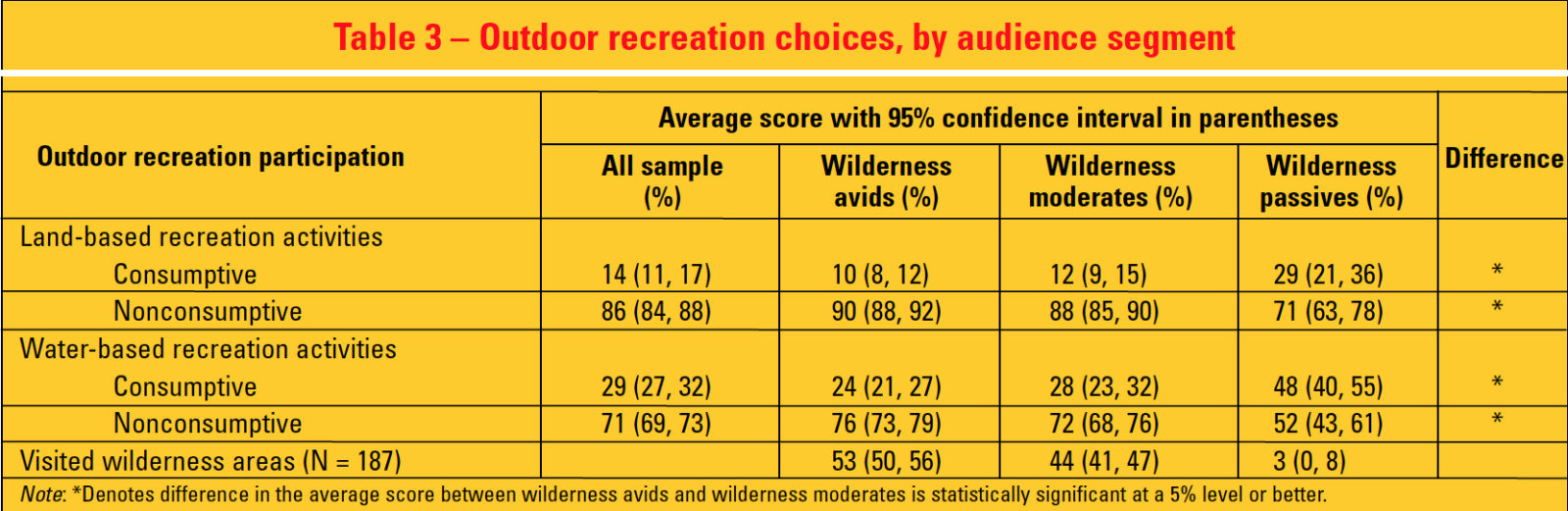

Respondents were divided into consumptive and nonconsumptive groups to analyze if perceived benefits of preserving wilderness areas vary among respondents based on their outdoor recreation choices. They were further divided into land-based and water-based activities, depending on their activity choices. As consumptive recreationists (e.g., hunters, fishers, etc.) are more likely to participate in some form of the nonconsumptive activity (e.g., walking, hiking, viewing, picnicking, etc.) in pursuit of their consumptive activities participation, we treated those respondents who participated in both activities as consumptive recreationists. In other words, we adopted a dichotomous classification based on whether they were consumptive recreationists (Ghimire et al. 2014).

Results indicated the clusters were dominated by nonconsumptive recreationists (land- or water-based) (Table 3). However, there were three times as many land-based consumptive recreationists in the cluster of wilderness passives (29%) than in the wilderness avids (10%). Likewise, there were twice as many water-based consumptive recreationists in the cluster of wilderness passives (48%) than in the wilderness avids (24%) (Table 3). Hence, consumptive recreationists were more likely to be wilderness pas- sives than wilderness avids.

In the survey, 187 respondents (approximately 14% of the sample) indicated they visited wilderness areas during the past 12 months, and 53% of them belonged to the cluster of wilderness avids. However, 44% of them belonged to the cluster of wilderness moderates, and 3% of them belonged to the cluster of wilderness passives (Table 3). Hence, respondents who visited wilderness areas were more likely to be wilderness avids or wilderness moderates.

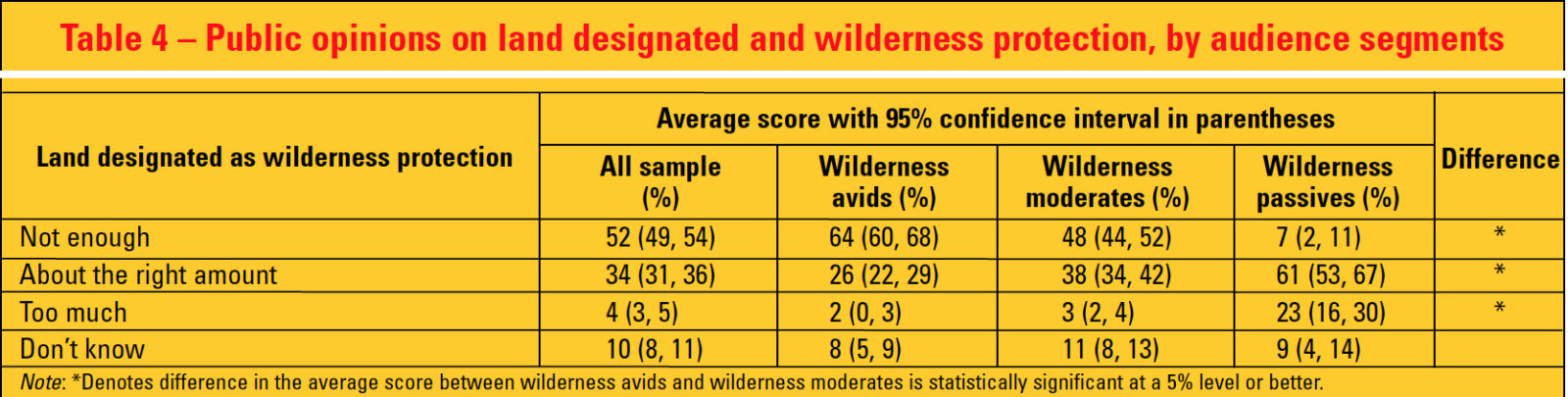

Land Designation and Wilderness Protection Two key statements about designation of natural land as wilderness and wilderness protection were analyzed to examine if respondents belonging to different clusters had different attitudes toward wilderness designation and protection. In

particular, the first question asked if the respondents thought the current amount of land Congress has designated as wilderness was enough. The second question asked the respondents if they supported designating more federal lands in their state as wilderness. Results indicated 64% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness avids and 48% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness moderates said the current amount of land Congress has designated as wilderness is “not enough,” compared to 7% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness passives (Table 4). In contrast, 61% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness passives and 38% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness moderates said it is “about the right amount,” compared to 26% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness avids (Table 4). To sum, respondents in the wilderness avids cluster were more likely to believe the current amount of land that the Congress has designated as wilderness is not enough, and respondents in the wilderness passives cluster were more likely to believe it about the right amount.

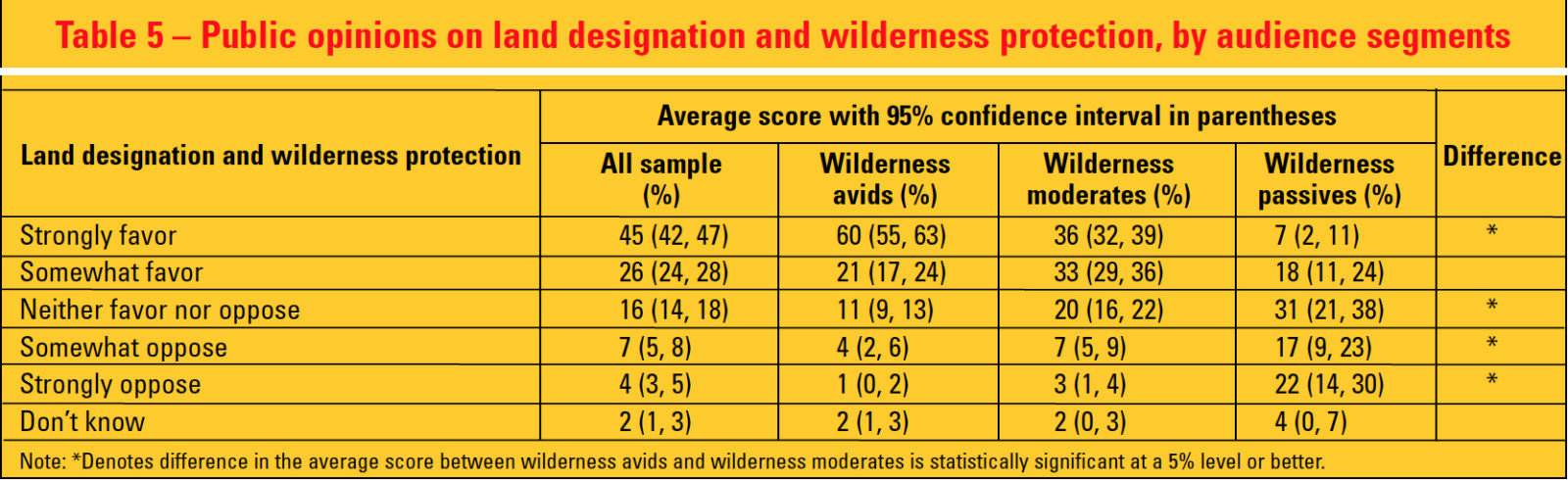

In the second question, 81% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness avids and 69% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness moderates favored (somewhat or strongly) designating more federal lands in their states as wilderness, compared to 25% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness passives. In contrast, 39% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness passives opposed (somewhat or strongly) designating more federal lands in their states as wilderness, compared to 10% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness moderates and 5% of respondents in the cluster of wilderness avids that opposed this proposal (Table 5). Hence, wilderness avids or wilderness moderates were more likely to favor designating more federal lands as wilderness, compared to wilderness passives.

Discussion and Conclusion

Public views on wilderness are important determinants of continued political support for land designation and wilderness protection (Stankey 2000). It is, thus, important to understand how people with different demographic characteristics and outdoor recreation choices value perceived benefits from preserving wilderness areas. Agencies and conservation groups may find this information valuable to understand characteristics of the public who perceive benefits from preserving wilderness areas distinctly and focus their education/outreach to garner additional support for land designation and wilderness protection. As wilderness passives or wilderness moderates perceive fewer benefits from preserving wilderness areas, educating them on a wide range of wilderness benefits may help in increasing their support for wilderness protection and land designation.

These findings also help convey the potential implications of future demographic changes on land designation and wilderness protection in the United States. Because of expected structural changes, the share of elderly people, females, college graduates, urban residents, and nonconsumptive recreationists is expected to grow in the future (Shrestha and Heisler 2011; Bowker et al. 2012). A larger share of elderly people could have a negative effect, but a larger share of females, urban residents, college gradautes, and nonconsumptive recreationists could have a positive effect on land designation and wilderness protection. Regardless of the nature of demographic changes, investment in outreach and education campaigns is likely to lead to greater support for land designation and wilderness protection in the future. However, more research is warranted to ascertain net effects of demographic changes on the future of wilderness protection. Finally, statistical analyses used in this study examine the behavior of a group in general, but they may fail to reveal the underlying variations among subsegments therein. Hence, the results may not be generalizable to specific individuals.

RAMESH GHIMIRE is a postdoctoral research associate in the Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources at the University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA; email: ghimire@uga.edu.

GARY T. GREEN is an assistant dean of academic affairs and associate professor in the Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources at the University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA; email: gtgreen@uga.edu.

NEELAM C. POUDYAL is an assistant professor in the Department of Forestry, Wildlife, and Fisheries at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA; email: npoudyal@utk.edu.

KEN CORDELL is a scientist emeritus at the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute and the USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Athens, GA, USA; email: kencordell@gmail.com.

VIEW MORE CONTENT FROM THIS ISSUE

References

Bowker, J. M., A. E. Askew, H. K. Cordell, C. Betz, S. J. Zarnoch, and L. Seymour. 2012. Outdoor Recreation Projection in the United States – Projections to 2060. Asheville, NC: USDA Forest Service, SRS.

Bowker, J. M., H. K. Cordell, and N. C. Poudyal. 2014. Valuing values: A history of wilderness economics. International Journal of Wilderness 20(2): 26–32.

Cordell, H. K., C. J. Betz, G. T. Green, S. Mou, Leeworthy, P. Wiley, J. J. Barry, and D. Hellerstein. 2004. Outdoor Recreation in 21st Century America: A Report to the Nation: The National Survey on Recreation and the Environment. State College, PA: Venture Publishing.

Cordell, H. K., C. J. Betz, B. Stephens, S. Mou, and G. T. Green. 2008. How Do Americans View Wilderness. Wilderness Research Report. Athens, GA: University of Georgia.

Everitt, B. S., S. Landau, M. Leese, and D. Stahl. 2011. Cluster Analysis. London: Wiley.

Ghimire, R., H. K. Cordell, A. Watson, C. P. Dawson, and G. T. Green. 2015. Result from the National Wilderness Manager Survey 2014. Fort Collins, CO: USDA Forest Service, RMRS.

Ghimire, R., G. T. Green, H. K. Cordell, A. Watson, and C. P. Dawson. 2015. Wilderness stewardship: A survey of National Wilderness Preservation System managers. International Journal of Wilderness 21(1): 23–27, 33.

Ghimire, R., G. T. Green, N. C. Poudyal, and H. Cordell. 2014. Do outdoor recreation participants place their lands in conservation easements? Nature Conservation 9: 1–18.

NSRE. 2008. National Survey on Recreation and the Environment, 2008. Athens, GA, and University of Tennessee, Knoxville: USDA Forest Service, SRS.

Rabe-Hesketh, S., and B. Everitt. 2004. A Handbook of Statistical Analyses Using Stata. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall.

Shrestha, L. B., and E. J. Heisler. 2011. The Changing Demographic Profile of the United States. Washington, DC: Congres- sional Research Service.

H. 2000. Future Trends in Society and Technology: Implications for Wilderness Research and Management. Fort Collins, CO: USDA Forest Service, RMRS.