Arches National Park, Moab, UT. Photo credit: Quinn Brett.

Wheelchairs in Wilderness: One User’s Perspective on Ways to Improve Wilderness Accessibility for All

by QUINN BRETT and ERIN DRAKE

Stewardship

December 2023 | Volume 29, Number 2

Lately, I’ve had a strong desire to return to my favorite wilder- ness area and attempt the area’s rim-to-river trail. This route begins just a few miles down the road from the area’s visitor center and traverses 7 miles to the mouth of the river. I ran it for the first time in 2016 and enjoyed the entire journey. For me, this was a quintessential wilderness experience – I experienced physical challenge, solitude, and almost overwhelming natural beauty.

As I recall, planning for this endeavor had the usual considerations. Could I get water from the stream that intersects the trail? What would the weather be like? How would my knees feel with the downhill pounding and uphill march?

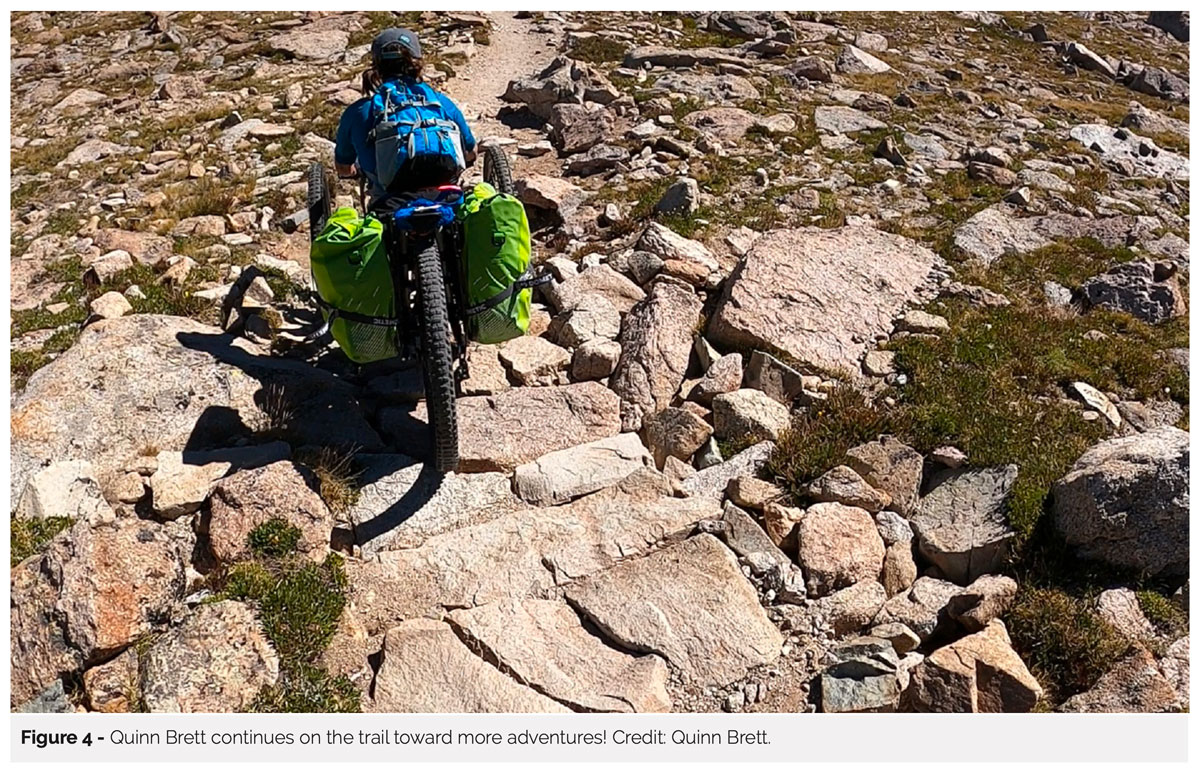

Going back, these days looks quite a bit different. In 2017, I suffered a spinal cord injury and am now paralyzed from the waist down. Today, I’m drawn to wilderness for the same reasons as I was before. I still want to spend time in the outdoors, push my lungs and heart physically, challenge my mind, and experience awesome adventures. And this time, instead of running, I will be using my wheelchair.

I crave big adventures, and part of the fun is the preplanning. However, the logistic preparations for any sort of trail experience as a person with a disability is often incredibly challenging. It requires even more effort. I know my own capabilities and those of my different wheelchairs. Each wheelchair has its own strengths and drawbacks on specific terrain features. The biggest crux is knowing what exactly those terrain features are. How wide is the trail on average? Are there significant pinch points? What about steep cross slopes or large steps? I have learned through past trail experiences and trail knowledge that the developed and managed use of a trail, as well as trail class, help to inform my decision. For example, if the trail is used by stock animals, it generally has design parameters that also work well for mobility devices. The trail is often wide enough, and the lack of steps and water bars work well for both stock users and me.

I am lucky to have had eyes on this trail previously, helping to increase my confidence. Although I have had confident moments that were shattered because my eyes and memory before my injury were not clued into my needs now that are impacted by common trail barriers and other features.

Research for any kind of trail can be extensive. I start with the internet. First, I pull up an online map of the wilderness area. Online scouting gives an idea of where trails are located and a basic rating system of subjective difficulty. Then begins the in-depth research of scouring photos, looking for images of the parking lot(s), bathroom(s), and trail itself; photos that show the tread, the rocks, roots, gravel, width, bridges, steps. I am not looking at photos of the view or scenery; I will enjoy those aspects of the area if I get on the trail.

I’m scanning photos for indicators of accessibility. Is there an accessible parking spot marked? Accessible parking spots ensure that I have enough room to access the side of my van and load or unload my wheelchair. What is the parking lot surface type? Thick gravel versus packed gravel versus pavement make a difference, especially when maneuvering around in my wheelchair and unloading my other mobility devices.

A big disappointment is when a trail looks possible online, but then I can’t actually get to the trail because there is some sort of gate. I have encountered roll-overs that are too narrow for my mobility device. There are a variety of older metal cattle or horse gates that you must step through or reach and hitch/unhitch a closing mechanism. Often these steps are too abrupt and awkward for my wheels to roll over, or it is too high for me to even attempt. And gates located on a slope of any kind make two-handed operations even more difficult. While I have good hand function, my friends with different disabilities have a hard time with just the latching function or chaining of these gates because they have reduced grasp and dexterity.

I know we all must do varying degrees of planning for a trail experience given the vast spectrum of desired experiences, physical fitness, crowd levels, and permits required. It just seems now, as a person with a disability, the pre-trip and during-trip barriers that pre- vent an experience from occurring are more common and often unidentified because there is a lack of understanding of what specific information is needed.

All these thoughts and I haven’t even arrived yet on the trail! Based on my research, the rim-to-river trail in this wilderness area is open to hikers and stock use and looks feasible if I use my battery power–assisted wheelchair with a hand crank (I’m in a kneeling position while using this particular wheelchair). Given the distance, the location, and it being my first time there, it feels smart to bring a friend.

When we arrive, the parking lot is crowded, so we end up using a pull-out on the side of the road. It was tight but navigable in my wheelchair. Getting on the trail is no problem with no gates to negotiate. I roll over the same roots and boulders my friend steps over. A little over a mile on the trail we encounter a foot bridge. This bridge is only about a foot wide, too narrow for my wheelchair. Luckily, because this trail allows for stock there is a wider swath of earth cleared next to the foot bridge that directs stock traffic through the stream. I do need to be mindful of time of year (e.g., water runoff levels, riverbed consistency); luckily, this day the water is low and the stream bed’s surface consistency is not much different from the trail tread. A half mile or so later, we come across a loose sandy section of trail, where I start losing traction, sort of “swimming” in the sand. When this happens, I ask my friend to give a gentle push down on my back tire, providing extra weight to gain traction and move myself forward.

Short-lived and minor trail setbacks like this are regular occurrences for me. And they can add up to be very timing consuming over the course of an entire trail. We continue, making similar time per mile as I would when I was hiking with my two feet. Our intention was to get to a junction where the trees opened up providing stellar views of the surrounding scenery. Just before the junction, fears that were instilled when I looked at photos online come to life. The trail now cuts into a steep mountainside. The slope and subsequent erosion mean the overall trail width is now narrower. If I encounter any roots or boulders or more eroded trail sections, especially if those obstacles are on the uphill side, I can be incredibly unstable. It is physically and men- tally fatiguing to manage terrain like this. And if the slope is too steep, it’s impassable for my wheelchair. But for now, I find a spot where I feel comfortable resting on my own and ask my friend to hike ahead around the bend.

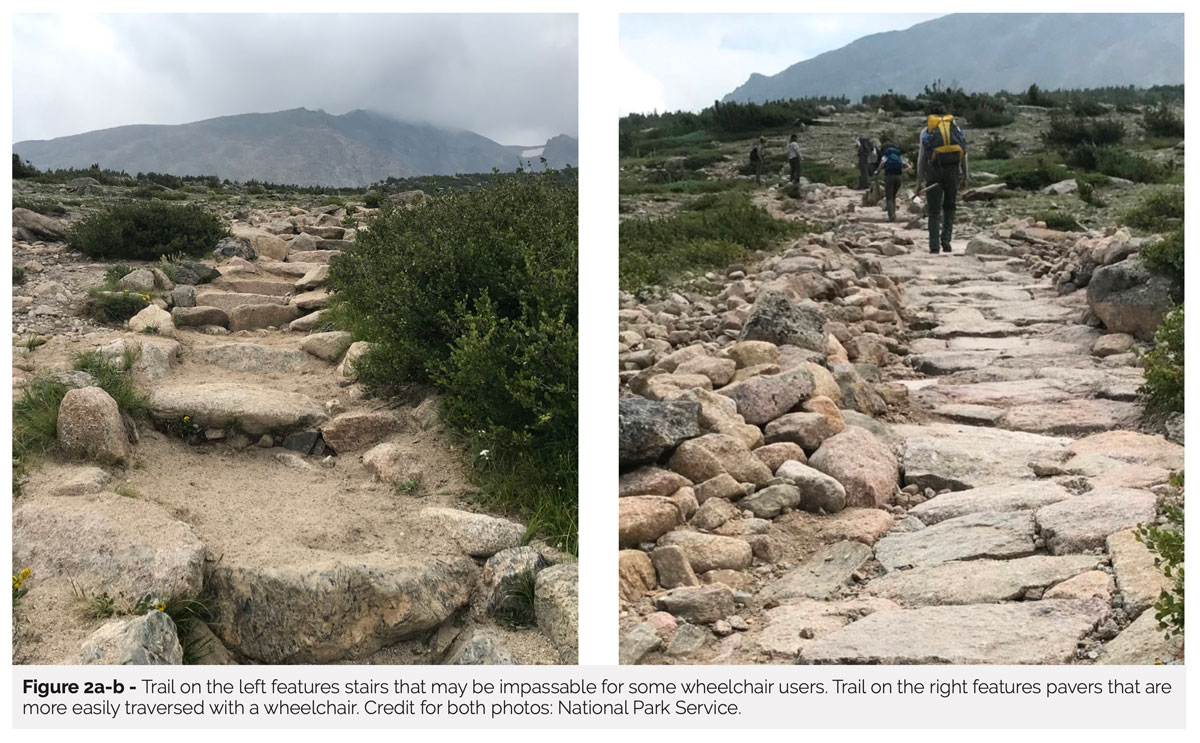

They scout to gauge how much longer this narrow and more side-sloped terrain lasts and find a spot where if I need to, I can safely turn around. Upon their return, my friend tells me that just past the bend it levels out again, so we carry on. Farther up the trail, we encounter our next obstacle: a series of steps (see Figure 2a-b). Steps might be doable for some wheel- chairs, but this depends on several factors. How high are the steps? What is the distance between steps? What type of wheelchair am I using? Am I by myself? How many friends do I have along to help? These steps look pass- able, so I start moving up them with the help of my friend.

Sidebar 4:

Accessibility best practice: Measure and describe key trail attributes online and in visitor centers/kiosks. Trail attributes include:

- Length

- Surface

- Width

- Running slope

- Cross slope

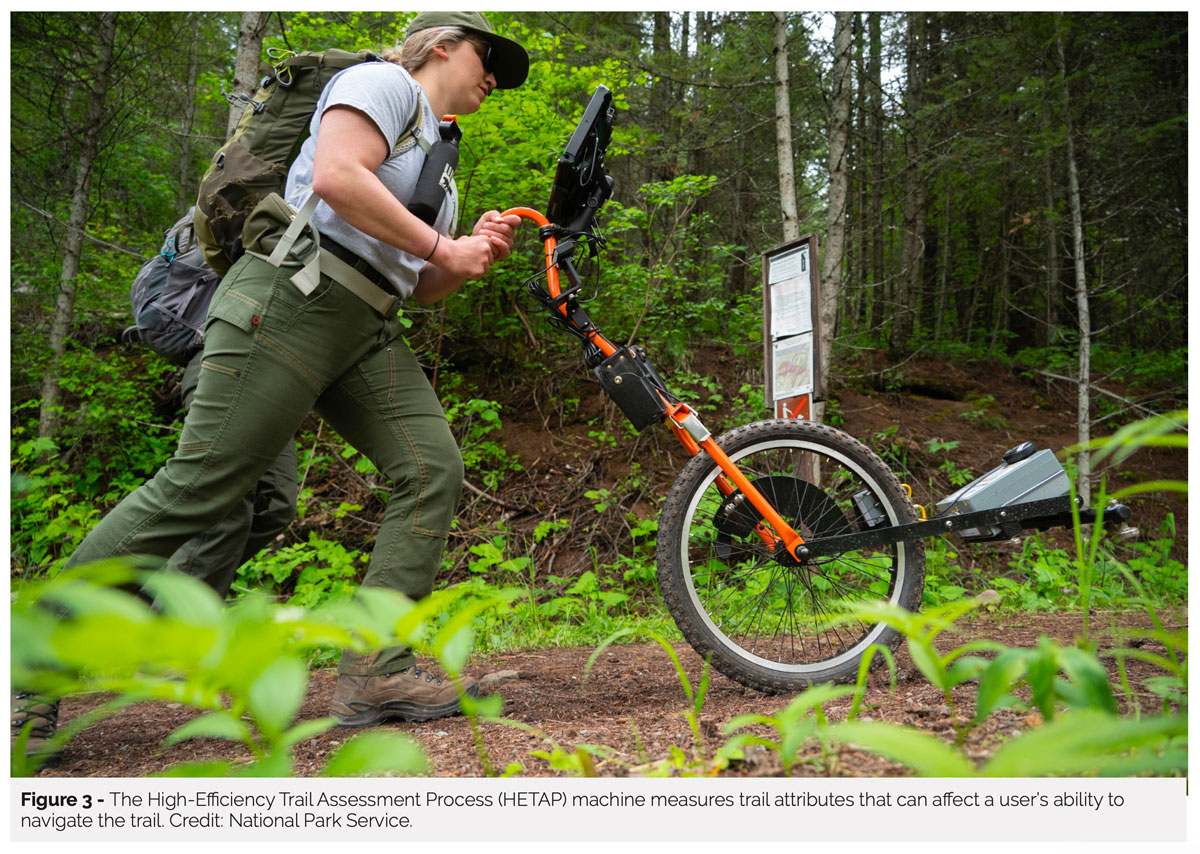

Don’t have this information immediately available? Data collection techniques include:

- Manual collection with basic equipment

- High-Efficiency Trail Assessment Process (HETAP) machine

- Existing research technology, such as GIS, Lidar, Drones, etc.

Feeling overwhelmed? Communicating these attributes, alongside accompanying photos, is ideal for all trails (and the entirety of every trail). If this isn’t immediately possible, pick a couple of the most popular trails, and most popular sections of these routes, to describe for now. Every little bit helps!

We continue to an opening in the trees, not quite yet at our intended destination. As we dig into our packs for a snack, I glance at the time. Due to the terrain being more involved in the last half, our pace has slowed. Even though the trail continues for three more miles to the banks of the river, we opt to turn around here. If I want to see the river, I’ll need to plan for a longer day out on the trail next time. While I know it’s the journey, not the destination, I would have appreciated more descriptive trail information and images that can help better prepare users for the trail challenges I encountered today.

Making thoughtful, proactive information-sharing about trails and conditions more readily available is a good starting point. This information equips potential recreationists, including people with disabilities, with a foundation from which we all can assess our interest and compatibility.

Upon return from this and many other wilderness adventures, I am grateful for the physical ability and desire to still explore our natural world. I am also grateful to have access to a variety of wheelchair types that support me in experiencing wilderness. For me – and many of us – physical movement is helpful for movement of thoughts and alleviation of pain, anxiety, and so forth. Many people with disabilities have secondary health issues. The mental and physical health benefits provided by wilderness and other public lands improve those secondary complications. For instance, I deal with a great amount of daily nerve pain. When I am outside, moving and focused on my surroundings, my nerve pain is less present. People with disabilities can also encounter social stigmas and lowered expectations perpetuated by people without disabilities, where recreation opportunities are often glazed over as “not doable” so therefore “not desirable.” On the contrary, we all want to explore and bond with each other and the environment through our experiences in them.

Remember, the Wilderness Act includes a recreational public purpose. As a wilderness stewardship community, how can we support inclusive recreation for all people to experience wilderness? Making thoughtful, proactive information-sharing about trails and conditions more readily available is a good starting point. This information equips potential recreationists, including people with the disabilities, with a foundation from which we all can assess our interest and compatibility. Information-sharing also creates space for discussion about other equity-based, trip-preventing issues such as general awareness, economic costs, and transportation (among other issues) that may limit who is able to physically experience wilder- ness. I have had some of my best outdoor experiences in the wilderness, and I am hopeful that more people, of all kinds, are able to experience their own meaningful connection with wilderness for years to come.

About the Authors

QUINN BRETT is a world-record-holding athlete and public lands employee whose physical ability took a dramatic shift in 2017 after suffering a spinal cord injury, paralyzed from the waist down. She is an adaptive Recreation Consultant and owner of Dovetail Trail Consulting; email: dovetailtrails@gmail.com

ERIN DRAKE is the communication and outreach specialist for the National Park Service Wilderness Program. She leads internal and external communications for wilderness, collaborating with parks, regions, national programs, and partners; email: erin_drake@nps.gov

Read Next

Reflections on Wilderness 60 Years after the Civil Rights and Wilderness Acts

America’s dominant narrative of the origin of a beloved wilder- ness often centers Aldo Leopold in a heroic fight at the turn of the century against rapid industrialization that occurred at the expense of nature.

Removing the Wilderness Illusion: Emerging Professionals Explore Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in Wilderness

From the eyes of four emerging professionals in land management come four different wilderness stories.

Medicine Fish Is Leading the Way to Heal, Build, and Inspire Menominee Youth through the Wild and Scenic Wolf River: An interview with Bryant Waupoose Jr., Founder of Medicine Fish

From a bird’s eye view, the Menominee Reservation is a forested oasis in sharp relief from neighboring landscapes of dairy farms spanning northeastern Wisconsin.