Wenaha Wild and Scenic River, Oregon. Photo Credit: Robert Burns

Examining Satisfaction and Crowding in a Remote, Low Use Wilderness Setting: The Wenaha Wild and Scenic River Case Study

Science & Research

December 2018 | Volume 24, Number 3

PEER REVIEWED

ABSTRACT The remote Wenaha Wild and Scenic River (WSR) in eastern Oregon is managed for four remarkable values: recreation, scenery, wildlife, and fisheries. Even on low use areas such as the Wenaha WSR, it is critical that managers understand visitor activities, as well as their attitudes. The purpose of this case study was to collect data about summer recreational use of the Wenaha WSR to help managers better understand visitor use and attitudes related to use capacity. Visitor surveys were conducted at trailheads and camping areas accessing the river. Results indicated visitors were satisfied with their visits, and crowding is minimal. Results are discussed in connection with the recently developed Interagency Visitor Use Management Framework.

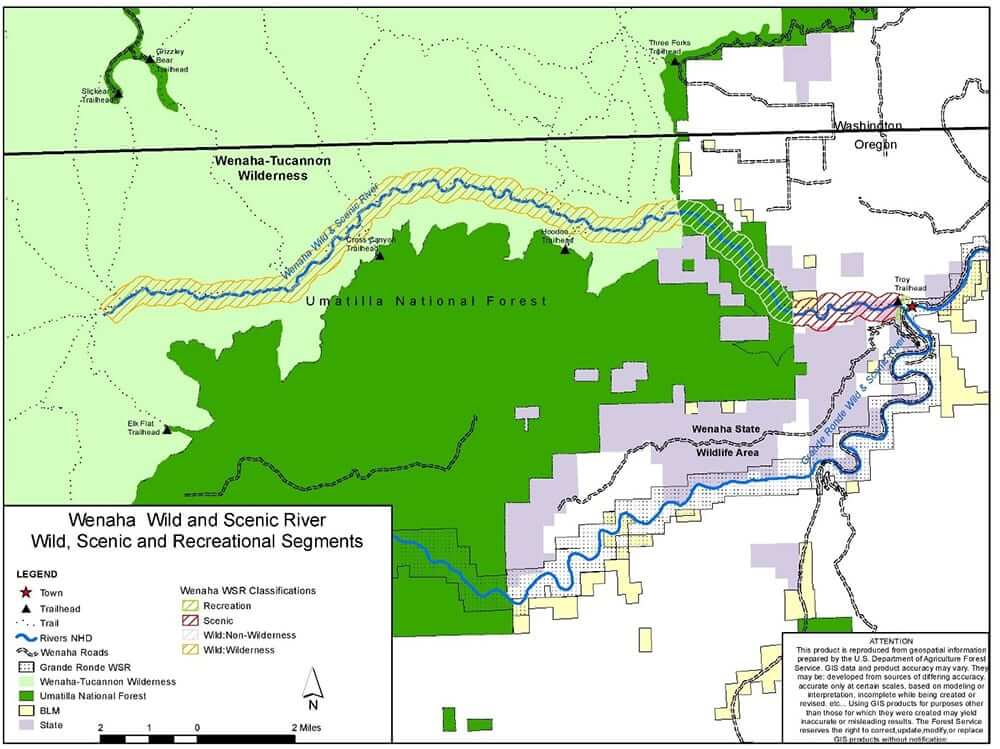

The Wenaha River is 21.6 miles (34.8 km) long, situated in the northeastern corner of Oregon, USA. The River begins in the federally designated Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness Area (within the Umatilla National Forest of northeastern Oregon) at the confluence of the north and south forks of the Wenaha River. The Wenaha Wild and Scenic River (WSR) was designated in 1988, and the Forest Service determined it to possess four outstandingly remarkable values (ORVs): recreation, scenery, wildlife, and fisheries (USDA 1992). The river is surrounded by additional federal and state protected public lands, managed by the Bureau of Land Management and the state of Oregon. The river terminates in the community of Troy as meets the Grande Ronde River, and a small section is fronted by private landowners and business owners.

This largely remote wilderness-setting river provides an excellent case study to examine low use wild and scenic rivers, especially those with Recreation ORVs. Literature focusing on visitors to wild and scenic rivers is relatively sparse (see Keith et al. 2008 for an overview; Smith and Moore 2011), and research specifically related to visitor capacity (also called user capacity, or social carrying capacity) on WSRs is very limited. Recent research has emphasized the need to focus not only on river ecology but also to strive to meet the high expectations set by river users (Verbos et al. 2017). Therefore, the purpose of this case study was to collect data about summer recreational use of the Wenaha WSR to help managers better understand visitor use and attitudes. The focus of this article is to explore the perceptions of visitors related to activities and user capacity, thus crowding, conflict, and satisfaction were assessed (Clark and Stankey 1979; Driver and Brown 1978; Lime and Stankey 1971; Manning 2004; Manning 2011; Stankey, Cole, Lucas, Petersen, and Frissell 1985; Wagar 1964, 1974).

Study Background

As the administrative authority of the Wenaha WSR, the Umatilla National Forest (NF) was required to complete a Comprehensive River Management Plan (CRMP). Data for this study was collected as part of the larger National Visitor Use Monitoring Program (NVUM) effort on the Umatilla NF in 2014. This specific dataset was collected in an effort to contribute data about social carrying capacity in support of the development of the Wenaha River CRMP (USDA 2015). Federal land managers must address social carrying capacity in order to uphold key components of the Wilderness and Wild and Scenic Rivers Acts. A capacity analysis was completed by the Umatilla NF in 2011 as part of the Wenaha River’s CRMP development (USDA 2013). This capacity analysis examined some variables related to social carrying capacity that focused on facilities and use, such as parking at trailheads, campsite use, and group size. A survey instrument was developed for this case study to provide additional data about these items, but equally importantly, to provide information about recreationists’ characteristics and experiences while visiting the study area. At the time of data collection the Draft Environmental Analysis (EA) was being developed. The Wenaha CRMP was released in June 2015 (after this study was completed).

Commonly used frameworks to assess visitor carrying capacity and define appropriate use and use levels include Visitor Experience and Resource Protection (VERP) (USDI National Park Service 1997); Visitor Impact Management (VIM) (Graefe, Kuss, and Vaske 1990); Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) (Stankey, Cole, Lucas, Petersen, and Frissell, 1985); and the Recreational Opportunity Spectrum (ROS) (Clark and Stankey 1979; Driver and Brown 1978). Most recently, the Interagency Visitor Use Management Council (IVUMC) developed a framework for federal managers to collaboratively develop, implement, and monitor sustainable visitor experiences (IVUMC 2017). Within the field of visitor use management, identifying and then managing visitor use is only one tool managers can employ to achieve and maintain desired resource conditions (IVUMC 2017). Key factors assessed when identifying visitor capacity include evaluating not just the numbers and types of visitation but also visitor perceptions. The important and complex constructs often measured related to visitor capacity include the interrelated variables of satisfaction, crowding, and conflict.

Figure 1 – Wenaha Wild and Scenic River.

Study Area

The Wenaha River is a free-flowing tributary of the Grande Ronde River in northeastern Oregon, where bull trout, coho and Chinook salmon, and steelhead thrive. The landscape is a maze of deep and precipitous canyons, with elevations ranging from 2,000 to 6,400 feet (609 m to 1,951 m). These widely varying elevations support a variety of plants, trees, and wildlife species, and provide prime habitat for Rocky Mountain elk. As noted earlier, the Wenaha WSR is surrounded by additional federal and state protected public lands.

This study focused on both land- and water-based recreational areas of the river corridor that crosses federal, state, and other jurisdictional boundaries. For the purposes of this study, the setting is defined as the Wenaha River Corridor (WRC). The WRC study area was divided into five smaller subunits for analysis based on their designated segments within the CRMP: the Wilderness section of the river corridor (in federally designated wilderness), the Wild section of the corridor (backcountry but not wilderness), the Scenic and Recreational corridor sections, and Non-corridor areas. All are described below.

Wilderness River Section

The majority (15.2 miles/24.5 km) of the Wilderness section’s 18.7 miles (30.1 km) runs through the Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness, within Umatilla NF boundaries. Four of the six trailheads sampled for this study provide direct access to this segment. They all have limited parking and facilities and are located just outside of the wilderness boundary. Visitors leave these areas on foot or horseback and descend as much as 3,000 feet (914 m) to the river. Upon reaching the river, visitors can follow the Wenaha River Trail, which runs 31.3 miles (50.4 km) from Troy to the Timothy Springs trailhead. The Wenaha River Trail runs along the north side of the river, but can still be accessed from the south simply by crossing the river. Although there are no bridges, the water is low enough much of the year to cross in many places.

Wild River Section Non-Wilderness)

The remainder of the Wild section (3.5 miles/5.6 km) is outside of the wilderness, but still within Forest Service boundaries. It is most directly accessed by the Troy trailhead. This non-Wilderness area is similar in character to the Wilderness section.

Scenic River Section

The 2.7 mile Scenic section is outside of the wilderness and forest boundaries. There are BLM, state, and private lands in this part of the river corridor. Much of this section is still remote, providing opportunities for solitude similar to those provided by the Wild section. From the north, the Scenic section of the river is most easily accessed from the Troy trailhead. Visitors can follow the Wenaha River Trail, which connects to the Scenic section and continues to the Wild section. On the south side of the river, a portion of the Scenic section is easily accessed and utilized frequently by visitors camping on state lands. Car camping is common in this area, a short walking distance from the center of Troy.

Recreational River Section

This small 0.15-mile (.24 km) section joins the Grande Ronde and exists within Troy. Although summer months can be quiet in Troy compared to hunting and steelhead fishing seasons, this is a popular take-out location for rafters floating the Grande Ronde. On the south side of the river, state-managed campsites extend into the Recreational section of the corridor. On the north side, the Shilo Troy Resort is a privately owned business that provides developed camping opportunities on the Recreation section of the river. Of these 20 developed campsites, 7 available are located on the Wenaha (the remaining 13 campsites are on the Grande Ronde). At the time of data collection, eight individuals lived year-round in Troy, and utilized the river corridor daily. The Shilo Troy Resort also leases land in Troy to hunters in the fall, who leave their wall tents up year-round for convenience.

Methods

Instrumentation

An on-site survey was used to collect visitor data. The survey instrument included primarily quantitative items pertaining to sociodemographics, group characteristics, trip characteristics, activity participation, satisfaction, and crowding/conflict. Sociodemographic items included gender, age, education, income, racial and ethnic group identification, and home zip code. Group characteristics included group type (private or commercial) and the number of adults and children in the group. Trip characteristics included whether this was a first or repeat visit, year of first visit, number of days spent here or at other wildernesses or wild and scenic rivers, whether it was a day trip or overnight visit, primary destination, and length of stay.

Data Collection

Surveys were collected from mid-June through early August 2014 at trailheads and campsites providing access to the river. Forest Service managers were consulted to determine the best locations and times of day for conducting surveys. They identified four trailheads believed to provide the most popular access to the Wenaha river corridor. Surveys were also collected at campsites in Troy.

A total of 74 surveys were collected, which likely encompassed nearly all of the visitation that occurred in the WRC during this summer period (L. Randall [USFS], personal communication, October 2014). Only one visitor declined, yielding a response rate of 98.7%. Whereas in higher use areas more data can be collected and analyzed across various segments of the sample using the recreation area, this was not possible in the WRC due to the small sample size.

Results

Visitors in the study were almost exclusively non-Hispanic Caucasians. The majority of visitors were male (80%), with a mean age of 44 years. Slightly more than half (56.4%) possessed a bachelor’s degree or higher. Groups in the study area were generally small, and all were private (noncommercial) groups (note – there is currently only one permitted commercial outfitter and guide service in the Wenaha WSR; USDA 2015). Three-fourths of visitors were repeat visitors, and 43% reported recreating in the study area eight or more days in a typical year. Most visits (71.6%) were overnight (average stay was 3.3 nights), and day use visitors stayed an average of just over four hours.

Satisfaction

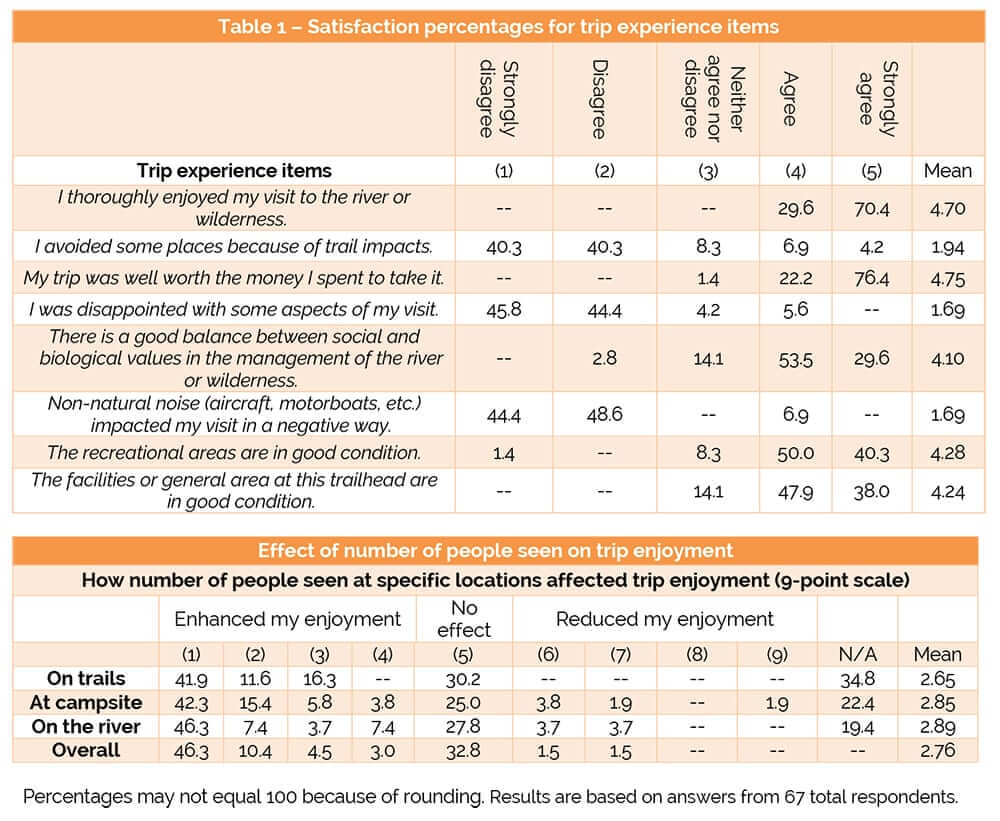

Respondents reported high levels of overall trip satisfaction: 71% reported that their trip was very good or excellent, and 22% reported their trip was perfect (mean = 4.76). Visitors were asked to rank specific satisfaction items; all were rated highly (Table 1).

Crowding and Conflict

Visitors used a modified 9-point crowding scale (Gigliotti and Chase 2014) to report specifically about the effect of number of people seen on the trails, at their campsites, on the river, and then how the number of people seen in total affected their overall trip enjoyment (Table 1). Mean responses indicated that the number of people seen tended to enhance visitor enjoyment a little on trails (mean = 2.65), at campsites (mean = 2.85) and on the river (mean = 2.89), and overall (mean = 2.76).

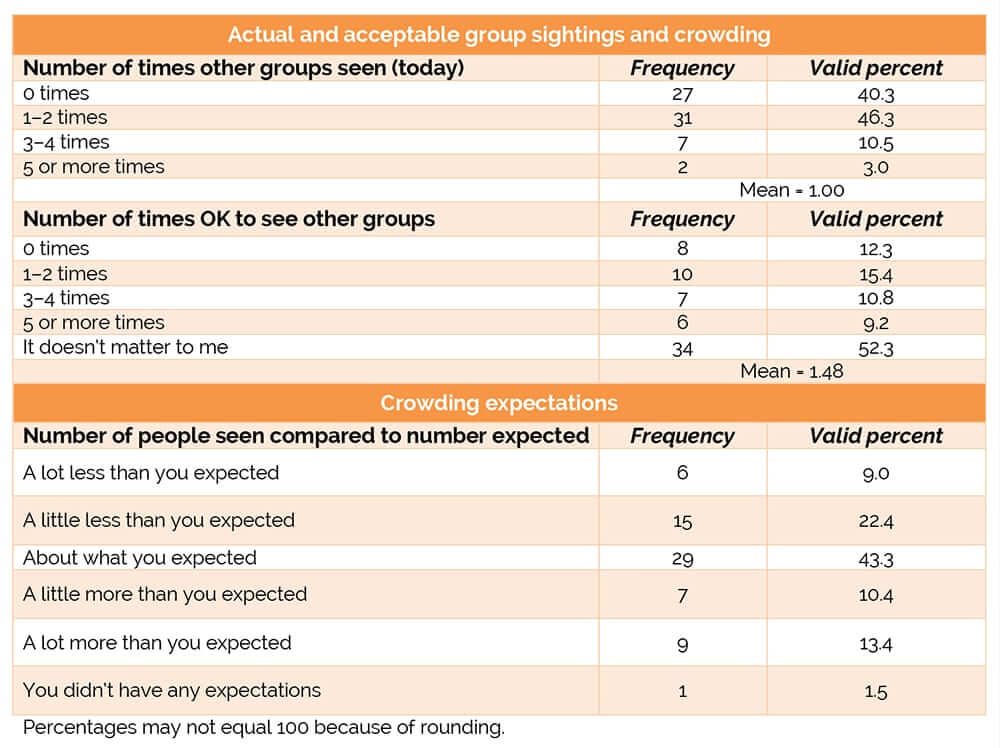

In general, respondents did not encounter very many other groups (Table 2). When asked how many times did you see other groups (today), the majority (86.6%) had seen other groups two or fewer times. A small percentage (10.5%) reported seeing others three or four times, and an additional 3.0% saw other groups five or more times. On average, visitors reported seeing other groups one time (mean = 1). When visitors were asked how many times is it OK to see other groups, the mean response was 1.48. Nearly half (43.3%) of respondents reported that the number of people seen on this trip was about what was expected (Table 2). Only 9.0% saw a lot less people than expected, and 13.4% saw a lot more. Only one person reported that they did not know what to expect.

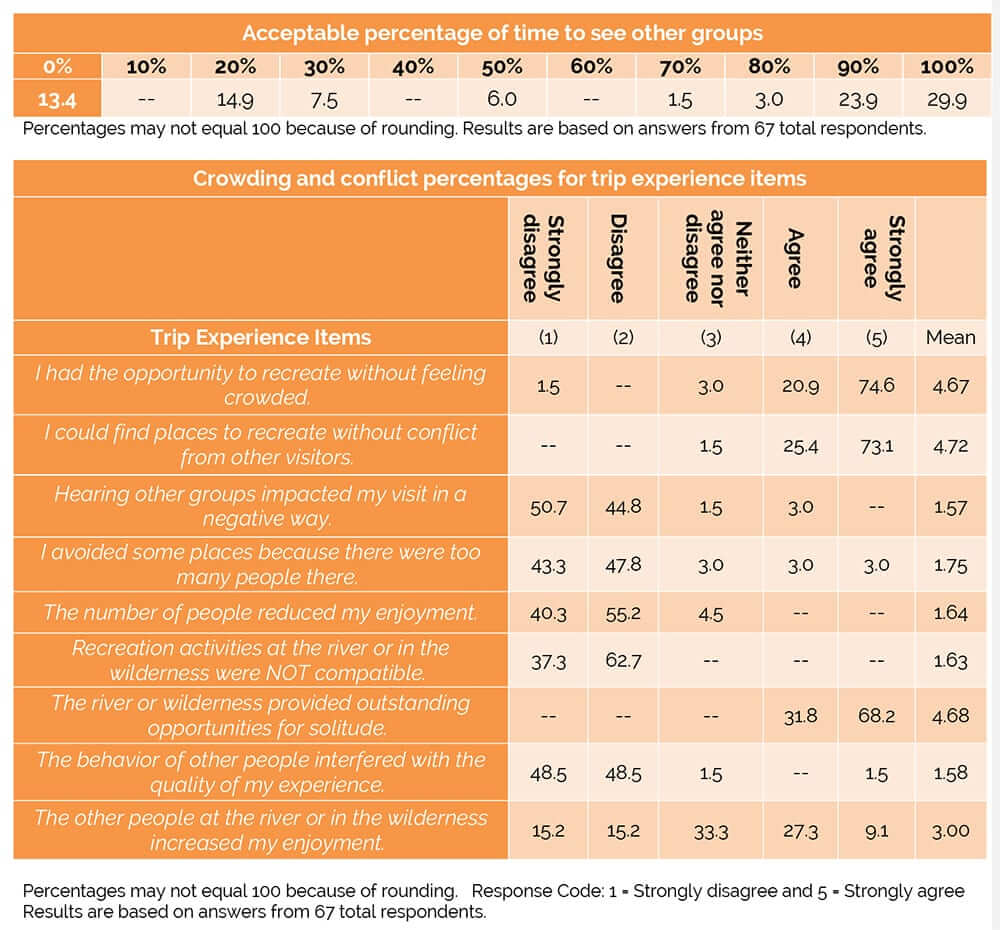

Respondents were asked about an acceptable percentage of time to see other groups while recreating during their visit in the study area (Table 3). Nearly one-third (29.9%) of the sample stated that it is acceptable to see other groups 100% of the time that they are recreating, and an additional 23.9% said that it is OK to see other groups 90% of the time. Only 13.4% stated that it is unacceptable to see other groups.

Positively and negatively worded statements were used to assess aspects of crowding and conflict (Table 3), and in general visitors did not report being crowded or experiencing conflict. Visitors were likely to be in agreement with the statements I had the opportunity to recreate without feeling crowded (mean = 4.67) and I could find places to recreate without conflict from other visitors (mean = 4.72). Visitors also were likely to agree that the area provided outstanding opportunities for solitude (mean = 4.68). Responses varied for the level of agreement with the statement the other people at the river or in the wilderness increased my enjoyment (mean = 3.00); one-third (33.3%) neither agreed nor disagreed. In addition, most disagreed that the number of people reduced my enjoyment (mean = 1.64).

Discussion

Visitors to the study area reported high levels of satisfaction. Open-ended responses also indicated satisfaction – all visitors made comments about what they liked most about the area, and many visitors spent time explaining these answers. When asked what they liked least, 73% of respondents either specified “nothing” or made jokes about the steep hike out or other similar comments. Better trail maintenance was by far the most common response when asked about suggestions for management, often referring to overgrown vegetation along the trails. They were specifically concerned about rattlesnakes or injury to either their horses or themselves. Also, while fewer visitors suggested it, better signage directing visitors to trailheads was mentioned several times.

Data also suggests that crowding and conflict are not a problem in the study area. A recently developed bivalent crowding scale was used, and respondents did report that the number of people seen enhanced their enjoyment (a little), rather than reducing enjoyment (Gigliotti and Chase 2014). Interestingly, in response to the statement the other people at the river or in the wilderness increased my enjoyment, visitors gave a neutral rating (mean = 3.00 on a scale of 1–5) – but also not a negative evaluation. The bivalent scale allows for the visitor to more easily rate enjoyment based upon the instance of seeing no other people, an important distinction when assessing visitation to remote areas. In addition, the actual group sightings (mean = 1.00) were less than the number reported as acceptable (1.48). When asked about an acceptable percentage of time to see other groups while recreating (overall), more than half of respondents stated that seeing others 90%–100% of the time is acceptable. These respondents represented different locations within the study area, not exclusively the higher use Recreational and Scenic sections, as might be expected. However, even though more than 50% of visitors said it was acceptable to see other groups 90%+ of the time, managers would not want to use that as a standard for management in an WSR, as opportunities for primitive recreation activities in remote and undeveloped settings is noted as a desired condition within the Wenaha WSR (USDA 2015). It is also unclear where in their visit (hiking, camping, etc.) respondents were noting it is acceptable to see others on their trip, so further research should address this. Crowding, conflict, and other normative preferences have actually been found to vary based on the format of the question (Donnelly et al. 2000), so using multiple questions to assess them is one way to minimize this assessment problem.

However, one important study limitation involved the timing of this study (summer only), which precluded researchers from collecting data during the hunting season when use may increase. It is recommended that managers monitor visitor use during spring and fall in order to fully understand visitor use on the Wenaha WSR.

Managers in other low use areas may want to consider conducting similar studies to gain a fuller understanding of visitor user capacity at low use sites, which could help in setting appropriate standards and thresholds for low use sites.

Management Implications and Conclusions

The results suggest that the Wenaha WSR is managed appropriately and that visitors are highly satisfied with their recreation experience. Managers in other low use areas may want to consider conducting similar studies to gain a fuller understanding of visitor user capacity at low use sites, which could help in setting appropriate standards and thresholds for low use sites. This in turn would provide managers with the opportunity to focus resources, including time, funds, and personnel, on areas that rate lower in satisfaction (IVUMC 2017; Interagency Wild and Scenic Rivers Coordinating Council 2018). Using adaptive management and the sliding scale approach advocated in the Interagency VUM framework will allow managers to more efficiently manage recreation sites that receive varying levels of use for high quality sustainable recreation experiences (IVUMC 2017; Verbos et al. 2017). Once initial visitor use capacity indicators, standards, and thresholds are developed through appropriate research, managers at low use settings such as the Wenaha WSR can then monitor on longer interval bases, for example, every five years instead of annual monitoring that might be required in high use settings (unless some sort of condition change is noted in the interim) (IVUMC 2017; Interagency Wild and Scenic Rivers Coordinating Council 2018). Based on the results of this study, the Wenaha WSR setting could be seen as a test case for implementing the new VUM framework at low use and remote natural resource sites (IVUMC 2017; Verbos et al. 2017).

DR. ROBERT C. BURNS is professor and director of the West Virginia University Division of Forestry and Natural Resources; email: Robert.Burns@mail.wvu.edu.

ASHLEY R. POPHAM is a resource assistant for the US Forest Service, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon; email: apopham@fs.fed.us.

DR. DAVID SMALDONE is associate professor of Recreation, Parks and Tourism Resources at the West Virginia University Division of Forestry and Natural Resources; email: David.Smaldone@mail.wvu.edu.

References

Clark, R. N., and G. H. Stankey. 1979. The Recreation Opportunity Spectrum: A Framework for Planning, Management, and Research. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report PNW-98. Portland, OR.

Donnelly, M., J. Vaske, D. Whittaker, and B. Shelby. 2000. Toward an understanding of norm prevalence: A comparative analysis of 20 years of research. Environmental Management 25(4): 403–414.

Driver, B. L., and P. J. Brown. 1978. The opportunity spectrum concept and behavioral information in outdoor recreation resource supply inventories: A rationale. Proceedings of the Integrated Renewable Resource Inventories Workshop. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RM-55. 24-31.

Gigliotti, L. M., and L. Chase. 2014. A bivalent scale for measuring crowding among deer hunters. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 19(1): 96–103.

Graefe, A. R., F. R. Kuss, and J. J. Vaske. 1990. Visitor Impact Management: The Planning Framework. Washington DC: National Parks and Conservation Association.

Interagency Visitor Use Management Council. 2017. Visitor Use Management Framework: A Guide to Providing Sustainable Outdoor Recreation. Available at https://visitorusemanagement.nps.gov/VUM/Framework.

Interagency Wild and Scenic Rivers Coordinating Council. 2018. Steps to Address User Capacities for Wild and Scenic Rivers. Unpublished technical report. Available at https://www.rivers.gov/documents/user-capacities.pdf.

Keith, J., P. Jakus, and J. Larsen. 2008. December. Impacts of Wild and Scenic River Designation. Unpublished Report for the Utah Governor’s Public Lands Policy Coordination Office. Logan: Utah State University.

Lime, D. W., and G. H. Stankey. 1971. Carrying capacity: Maintaining outdoor recreation quality. Recreation Symposium Proceedings. USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, 174–184.

Manning, R. 2004. Recreation planning frameworks. In Society and Natural Resources: A Summary of Knowledge (pp. 83–96). Jefferson, MO: Modern Litho.

Manning, R. E. 2011. Studies in Outdoor Recreation, 3rd ed. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press.

Smith, J. W., and R. L. Moore. 2011. Perceptions of community benefits from two Wild and Scenic Rivers.

Environmental Management 47(5): 814–827.

Stankey, G. H., D. N. Cole, R. C. Lucas, M. E. Petersen, and S. S. Frissell. 1985. The Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) System for Wilderness Planning. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report. INT-176. Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. Ogden, UT.

USDA Forest Service. 1992. Resource Assessment, Wenaha WSR. On file at the Pomeroy Ranger District, WA.

———. 2013. Wenaha Wild and Scenic River Capacity Analysis. On file at the Pomeroy Ranger District, WA.

———. 2015. Wenaha Wild and Scenic River Comprehensive River Management Plan. Available at https://www.rivers.gov/documents/plans/wenaha-plan.pdf.

USDI National Park Service. 1997. VERP: The Visitor Experience and Resource Protection (VERP) Framework: A Handbook for Planners and Managers.

Verbos, R., C. Vadal, P. Mali, and K. Cahill. 2017. The Visitor Use Management Framework: Application to Wild and Scenic Rivers. International Journal of Wilderness 23(12): 10–15.

Wagar, J. A. 1964. The Carrying Capacity of Wild Lands for Recreation. Forest Science Monograph 7. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters.

———. 1974. Recreational carrying capacity reconsidered. Journal of Forestry 72(5): 274–278.

Whittaker, D., B. Shelby, R. Manning, D. Cole, and G. Haas. 2011. Capacity reconsidered: Finding consensus and clarifying differences. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 29(1): 1–20.

Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, 16 U.S.C. § 1271 et. seq. (1968).

Read Next

Apologizing for Science-Based Decision Making in Protected Area Management

Apologizing for science promotes autocratic management that can easily be commandeered by sociopolitical agendas and bureaucratic systems.

Wilderness Giant: Stewart “Brandy” Brandborg Moves on at 93

Steward Brandborg was a phenomenal wilderness champion, the last wilderness advocate with ties to most of the founders of the modern wilderness movement.

Cultural Meanings and Management Challenges: High Use in Urban-Proximate Wildernesses

As outdoor recreation increases in popularity and metropolises grow larger, the issues facing urban-proximate wilderness and protected lands will continue to come to the forefront.