Stewardship

December 2015 | Volume 231, Number 3

By C. B. GRIFFIN

Enshrined into Section 4(b) of the Wilderness Act is the requirement that each wilderness management agency “shall be responsible for preserving the wilderness character of the area.” All four agencies have adopted policies that require them to preserve wilderness character (Landres et al. 2015). There are several question that Section 4(b) raises.

The first question, “What is wilderness character?” is answered in great detail in Keeping It Wild 1 (KIW 1) (Landres et al. 2008) and the updated version, Keeping It Wild 2 (KIW 2) (Landres et al. 2015). Although wilderness character has both qualitative and quantitative components, the focus of wilderness character monitoring in the Keeping It Wild strategies is on numerical measures with an accompanying narrative. This reductionist method makes it easier to quantify wilderness character, track changes over time, and to aggregate results across agencies and the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS).

The second question 4(b) raises is, “Is there a universal minimum standard for wilderness character?” Dawson and Hendee (2009) answer the question by saying there isn’t a minimum national standard. Each wilderness is unique, and managers must ensure that wilderness character doesn’t degrade below the condition when it was established. Long a part of air and water pollution laws, the principle of nondegradation has been applied to wilderness character to ensure that it doesn’t decline over time (Pinchot Institute for Conservation 2001; Scott 2014).

The third question has to do with the word preserving in Section 4(b), which also relates to the nondegradation principle. Restoration ecologists have to determine the point in history to which to restore an area. Agencies must establish a similar point in history – the baseline by which to judge whether wilderness character is being preserved (Pinchot Institute for Conservation 2001). The focus of this article is the question, “What is the point in history that federal land managers should use to establish the baseline for wilderness character in an individual wilderness area?”

The Reference Point for Preserving Wilderness Character

In simplest terms, a baseline – the “reference point against which change over time is measured and evaluated” (Landres et al. 2008) – is either when a wilderness area was designated or some other point in time. Several authors (Dawson and Hendee 2009; Worf 2001) using the concept of nondegradation, set a wilderness’s baseline as the time of designation (Dawson and Hendee include the possibility of using an earlier date – the date it is identified as a wilderness study area).

For 10 years, interagency documents have set a wilderness’s baseline as the date of designation (Landres et al. 2005), but gradually that has changed.1 Before KIW 1, Landres et al. (2005, p. 14) defined the ideal baseline as “the time of wilderness designation” and the practical baseline as “the first time this [wilderness character] monitoring is conducted.” Some of this language persisted into KIW 1, which declared that agency policies are to “prevent the degradation of wilderness character from its condition or state at the time the area was designated as wilderness” (Landres et al. 2008, p. 4). However, KIW 1 also lists two possible dates for determining baseline wilderness character: “the Time of Wilderness Designation or the First Time This Monitoring Is Conducted.” KIW 1 goes on to say, “Ideally, this baseline is documented at the time a wilderness is designated. For wildernesses that have already been designated, appropriate historical data, if available, should be used to describe the baseline condition retrospectively. However, few existing wildernesses actually have this information. Therefore, baseline condition would most likely be documented from the first time this monitoring is implemented, even though such a description would not give an accurate picture of how the wilderness has changed since the time of designation” (p. 11).

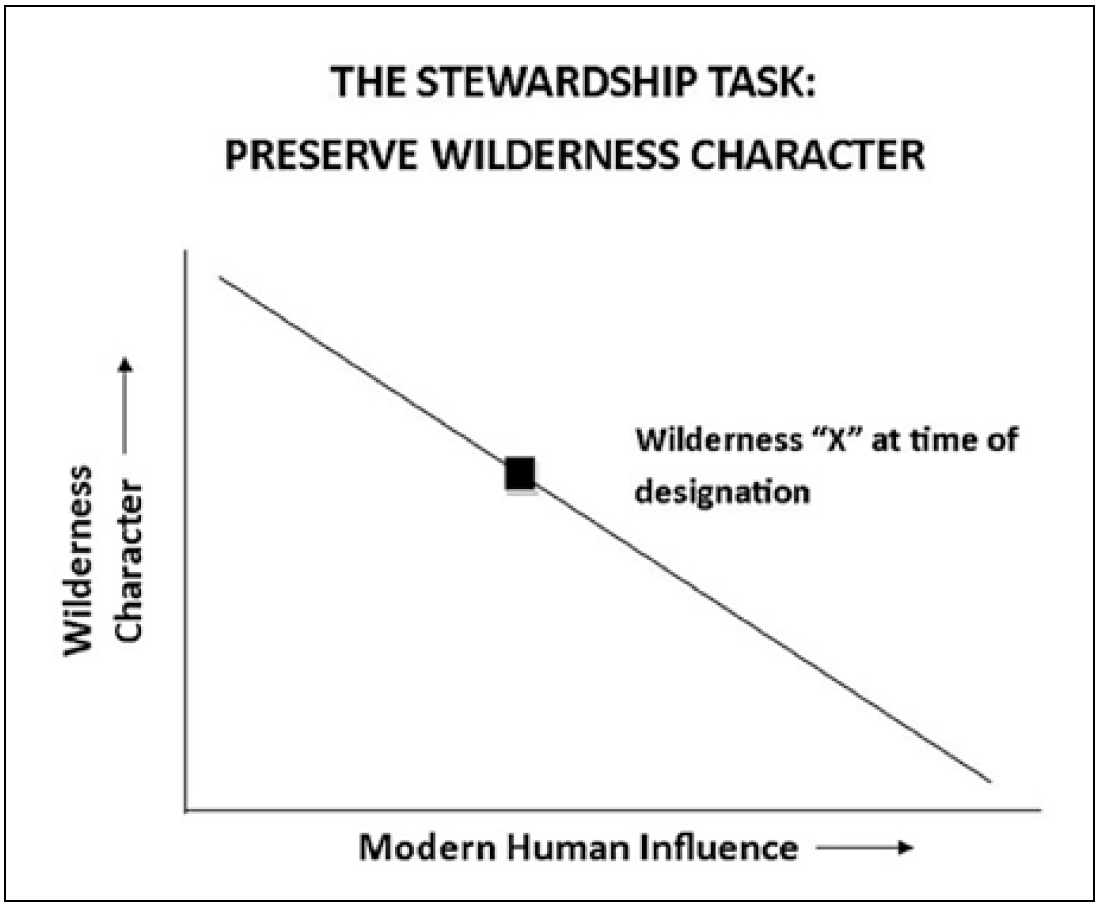

In a 2008 presentation, Preserving Wilderness Character, Landres utilized a widely used graphic that clearly shows that the baseline for wilderness character is the time of designation (Figure 1). In describing the figure he says, “The Wilderness Act and all agency policies clearly state that whatever the status of wilderness character is at the time of designation, the agencies are to not let this status degrade, or slide down on this graph” (Landres 2008).

One year later, in the 2009 Technical Guide for wilderness character monitoring (Landres et al. 2009), some of the language had softened with respect to the baseline question. “Appropriate historical data, if available, may be used to describe the baseline condition retrospectively. Because few existing wildernesses actually have this information, baseline condition would most likely be described from the first time this monitoring protocol is applied, even though such a description will not give an accurate picture of how the wilderness has changed since the time of designation” (p. 13).

KIW 2 keeps the two possible dates for baseline (designation or when wilderness character moni- toring was first completed using all measures), and it continues the differentiation between ideal (date of designation) and the practical baseline for establishing a designated area’s wilderness character. Later in the document that distinction disappears: “The first year that data for all measures have been collected using this interagency strategy forms the baseline.”

The 2008 KIW 1 document indicates the onus is on the agency to go back in time to create the baseline. By the 2009 Technical Guide, the should declaration of 2008 had softened to may go back in time. In 2009, the however agencies don’t generally have the historic data changed to because agencies don’t have the data, the date of the baseline won’t be the date of designation, rather it will be the date wilderness character monitoring is first applied. Both KIW 1 and the 2009 Technical Guide end with the same pronouncement: Using today as a wilderness area’s baseline will not provide an accurate portrayal of the wilderness’s real baseline – the one that existed at the time of designation.

A dramatic change appears in KIW 2. Instead of acknowledging that using today’s wilderness character monitoring as the baseline isn’t an accurate way to describe the real baseline, this section has been expunged: “Even though such a description would not give an accurate picture of how the wilderness has changed since the time of designation”. Elsewhere, KIW 2 still acknowledges, “From a legal standpoint wilderness character needs to be preserved from the time of wilderness designation” (Landres et al. 2015, p. 56). KIW 2 is therefore an example of the shifting baseline syndrome.

Shifting Baseline Syndrome

Pauly (1995) notes that the baseline for fish stocks keeps changing because each fisheries manager thinks the baseline is the species composition and quantity of fish that existed when they started. “The result obviously is a gradual shift of the baseline, a gradual accommodation of the creeping disappearance of resource species, and inappropriate reference points for evaluating economic losses resulting from overfishing, or for identifying targets for rehabilitation measures” (p. 1).

KIW 2 is aware of the possibility of a shifting baseline; it uses it as a rationale to support the need to document wilderness character using their protocol. “Experience and knowledge of a wilderness are often lost with staff turnover, and the baseline understanding of resource conditions shifts over time.” While documenting wilderness character today is necessary to ensure the baseline won’t shift in the future, it completely ignores the fact that we are starting with an already shifted baseline if we’re using today’s date as the baseline.

Nickas (2000) describes the implications of a proposed new Forest Service (FS) policy, which can be applied to this discussion. In Nickas’s figure 1, wilderness x has degraded below the standards for wilderness (the hatched area); therefore, the wilderness qualities must be improved. In contrast, the KIW 2 strategy essentially says the “wilderness x” baseline is today – it amounts to a lowering of the hatched area to meet what currently exists in Nickas’s figure 2. In a contradictory sentence, KIW 2 contains the following line: “Determining the trend in wilderness character is necessary but not sufficient because this trend could be upward but the condition is still degraded compared with the time of designation.” Yet there is no effort in KIW 2 to establish an area’s true baseline.

The approach articulated in KIW 2 will lead to establishing a baseline that isn’t an accurate portrayal of the legal requirement to maintain wilderness character from the date of designation. In essence, current wilderness character monitoring is beginning with a shifted baseline. For wilderness designated in 1964, that means 50 years’ worth of change will be ignored. Few will argue that wilderness character has improved across the NWPS.

Agencies’ Mixed Messages about the Date of Baseline

Some agencies have developed documents implementing KIW 1 for their wildernesses. Two national parks took different approaches when it came to the baseline question. Death Valley National Park (NPS 2012) used the year it was designated as wilderness (1994), whereas Olympic National Park went back five years from the present (Tricker et al. 2013). The NPS 2014 User Guide cited different approaches across the agency. Buffalo National River used the current year for developing a wilderness character map but used older data in some cases. Denali National Park and Preserve went back five years for the untrammeled quality and went back “as far as possible” for the other wilderness character qualities. “Denali also decided to create a ‘retrospective’ wilderness character map using professional judgment back to the time of wilderness designation to use in estimating change to wilderness character since it was designated wilderness” (NPS 2014, p. 214).

Regardless of when the baseline is actually set, it would seem like the baseline is that point in time – forever more. Not so for the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). In the 2012 BLM Implementation Guide it was noted that “trend would be determined by comparing the old value with the new value #1, and a new baseline would be established by the new value #2. (In essence, a new baseline might be produced every five years.)” The BLM document contains policy direction that codifies the shifting baseline into their wilderness character monitoring. KIW 2, to its credit, doesn’t follow the BLM direction. Whenever the baseline is established, it is the baseline by which all future monitoring is compared “to prevent slow, incremental degradation of wilderness character (Landres et al. 2015).

Establishing the True Baseline: The Role of Professional Judgment

Although obtaining data from when a wilderness area entered the NWPS from decades ago is difficult, it is incumbent upon federal agencies to establish the true baseline of wilderness character from the area’s date of designation. It will be difficult to obtain quantitative information about wilderness character from the date of designation. However, managers can use professional judgment to qualitatively describe wilderness character. Landres et al. (2008, 2009) declare that wilderness character data can be produced by using professional judgment. The 2009 Technical Guide goes so far as to say professional judgment could be a source of data, especially if it is “deemed crucial for assessing trends in wilderness character.” Furthermore, “these data will be used in the same way as any other data used in assessing trends in the indicator” (Landres et al. 2009). The use of professional judgment to establish wilderness character has carried over to KIW 2, which recommends that if there is no or poor-quality data, “local professional judgment may be used to assign a data value.” If scouring files doesn’t yield quantitative data, professional judgment can be used to establish wilderness character at the time of designation.

It is unfathomable that managers know nothing about the state of wilderness character from when the area was congressionally designated. Most agencies conducted studies prior to recommending areas to Congress. Professional judgment is widely used throughout agencies, and courts routinely defer to agencies’ professional judgment (Eccleston and Doub 2012).

Conclusion

Keeping It Wild 1 and 2 are monumental efforts aimed at helping agencies meet their legal obligation to preserve wilderness character. Both interagency documents are valuable because they are one of the best ways we have to ensure we are managing a system of wilderness according to one universal system – the NWPS – instead of managing them piecemeal. It is easy to find research to show that biophysical and social impacts in wilderness have increased since designation – Cole provided some earlier research in 1993 (Cole 2003). Unless there have been efforts to reverse these negative impacts, wilderness character has inevitably declined in these wildernesses since their designation.

Agencies must meet their legal requirement to preserve or increase wilderness character as it existed at designation. Since KIW 2 allows professional judgment to be used to help establish wilderness character today, it can and should also be used to develop the true baseline if historical quantitative data is lacking.

Describing wilderness character as it exists today is necessary but not sufficient to determine the wilderness character of an area. Using today as the baseline for wilderness character monitoring means we’ve already succumbed to a shifting baseline of what the true wilderness character is. Agencies must do the hard work of establishing wilderness character baselines as they existed at the time of designation. The public should settle for nothing less.

C. “GRIFF” GRIFFIN is a professor of natural resources management at Grand Valley State University in Michigan. She takes students on field trips to Colorado so that they can truly appreciate the West; email: griffinc@gvsu.edu.

VIEW MORE CONTENT FROM THIS ISSUE

References

Bureau of Land Management. 2012. Measuring Attributes of Wilderness Character. BLM Implementation Guide Version 1.5. Retrieved from http://www.wilderness.net/character.

Cole, D. 2003. Agency policy and the resolution of wilderness stewardship dilemmas. George Wright Forum 20(3): 26-33.

Dawson, C. P., and J. C. Hendee. 2009. Wilderness Management: Stewardship and Protection of Resources and Values, 4th ed. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Eccleston, C., and J. P. Doub. 2012. Preparing NEPA Environmental Assessments: A User’s Guide to Best Professional Practices. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Landres, P. 2008. Preserving Wilderness Character. Missoula, MT: Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, Rocky Mountain Research Station, USDA Forest Service. Retrieved from www.wilderness.net.

Landres, P., S. Boutcher, L. Merigliano, C. Barns, Davis, T. Hall, S. Henry, B, Hunter, P. Janiga, M. Laker, A. McPherson, D. S. Powell, M. Rowan, and S. Sater. 2005. Monitoring Selected Conditions Related to Wilderness Character: A National Framework. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-151. Fort Collins, CO: USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Landres, P., C. Barns, J. G. Dennis, T. Devine, P. Geissler, C. S. McCasland, L. Merigliano, J. Seastrand, and R. Swain. 2008. Keeping It Wild: An Interagency Strategy to Monitor Trends in Wilderness Character Across the National Wilderness Preservation System. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-212. Fort Collins, CO: USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Landres, P., S. Boutcher, L. Dean, T. Hall, T. Blett, T. Carlson, A. Mebane, C. Hardy, S. Rinehart, Merigliano, D. N. Cole, A. Leach, P. Wright, and D. Bumpus. 2009. Technical Guide for Monitoring Selected Conditions Related to Wilderness Character. General Technical Report WO-80. Washington DC, USDA Forest Service.

Landres, P., C. Barns, S. Boutcher, T. Devine, P. Dratch, A. Lindholm, L. Merigliano, N. Roeper, and E. Simpson. 2015. Keeping It Wild 2: An Updated Interagency Strategy to Monitor Trends in Wilderness Character Across the National Wilderness Preservation System. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-340. Fort Collins, CO: USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Draft, June 24, 2015.

National Park Service. 2012. Mapping Wilderness Character in Death Valley National Park. Natural Resource Report NPS/DEVA/NRR—2012/503. Fort Collins, CO: USDI National Park Service.

———. 2014. Keeping It Wild in the National Park Service: A User Guide to Integrating Wilderness Character into Park Planning, Management, and Monitoring. WASO 909/121797; Washington DC: USDI National Park Service. January 2014.

Nickas, G. 2000. Undesigning wilderness. Wilderness Watch 11(1): 1.

Pauly, D. 1995. Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 10(10): 430.

Pinchot Institute for Conservation. 2001. Ensuring the Stewardship of the National Wilderness Preservation System. A Report to the USDA Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, and US Geological Society. Washington, DC: Pinchot Institute for Conservation.

Scott, D. 2014. Nondegradation and the wilderness concept: Interpreting the Wilderness Act. International Journal of Wilderness 20(1): 8–12.

Tricker, J., P. Landres, J. Chenoweth, R. Hoffman, and R. Scott. 2013. Mapping Wilderness Character in Olympic National Park. Final Report. Retrieved from www.wilderness.net.

Worf, B. 2001. The new Forest Service Wilderness Recreation Strategy spells doom for the National Wilderness Preservation System. International Journal of Wilderness 7(1): 15–17.