Images of the Pacific Crest Trail. Photo credit © Annie Gencay.

Representations of the Pacific Crest Trail on Instagram: Implications of Social Media for Wilderness Management

Communications & Education

April 2020 | Volume 26, Number 1

The Wilderness Act directs wilderness managers to provide “outstanding opportunities for solitude” (Wilderness Act 1964). By contrast, social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter are built to share experiences with an audience. Despite their seemingly opposite purposes, wilderness is increasingly represented on social media tools: the Instagram hashtag (a label attached to a photo that allows other users to search for specific content) #wilderness has more than 6 million posts; the hashtag #wildernessculture has 10.6 million posts. Specific wilderness areas have fewer posts but are still represented: Colorado’s Weminuche Wilderness (#weminuchewilderness) has 4,500 posts, the Boundary Waters Canoe Area (#boundarywaters) has 45,000 posts, and the John Muir Wilderness has 25,000 posts for the hashtag #johnmuirwilderness and 72,000 posts for the hashtag #johnmuirtrail.

Sixty-nine percent of all US adults use Facebook, and 37% use Instagram (Pew Research Center 2019). Social media is particularly dominant among younger age groups with 90% of all 18- to 29-year-olds using at least one social media platform. Sixty-seven percent of 18- to 29-year-olds use Instagram; of those who do, 76% use it daily (Pew Research Center 2019). Of the various social media tools, Instagram is particularly conducive to broadcasting experiences to wide audiences. While Facebook posts are typically restricted to a user’s “friends” and unavailable for public viewing and searching, an estimated 72% of Instagram posts are available to anyone on the internet (Byrne 2014). In combination with the high frequency with which wilderness is portrayed on social media, the increasing ubiquity of these platforms suggests representations of wilderness on social media will continue to grow.

These factors have created a massive dataset about wilderness. Social media is primarily shared from a first-person perspective. Typically accompanied by a narrative of the user’s preferences, each post of wilderness depicts it as the user has experienced it. Such access to a person’s feelings about their wilderness experience provides a resource to rapidly gather data from a large population on their subjective experiences in wilderness. On Instagram, 100% of posts include a photo and thus provide a data point of what wilderness conditions looked like at a specific point in time, offering opportunities for windows into things such as camping density, campsite conditions, and species identification and surveying.

Simultaneously, this use of social media to bring wilderness experiences to a broader audience raises new considerations for wilderness managers. What does the wilderness experience look like, and how does it change, when visitors enter with a specific goal of sharing it? Do wilderness users perceive the presence of social media in the wilderness as a breach of solitude? Is solitude even among their priorities in entering wilderness? Wilderness users are finding answers to these questions, consciously or not, simply through continued use of social media within wilderness. If wilderness managers ignore the social media space, they risk missing full participation in these conversations.

This article explores the potential of Instagram as a source of information for wilderness managers by examining the components of Instagram posts and examining trends that emerge in user narratives and viewer comments. It uses the framework of thru-hikers of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) to understand wilderness representations and social media user experiences. Unless otherwise indicated, all referenced posts were found by searching the hashtag #PCTClassof2019. All posts are publicly available and do not require the user to grant permission to be viewed.

The Pacific Crest Trail on Instagram

A unique case study to examine social media as a dataset and to explore current wilderness trends can be found in thru-hikers’ representations of the Pacific Crest Trail on Instagram. A 2,650-mile (4265 km) route running from Mexico to Canada, the PCT passes through 48 wilderness areas across three states. Since thru-hikers are walking for several months, they have an extended opportunity to post – and viewers have an extended opportunity to observe – their journey in real time, uploading a photo to Instagram whenever internet access is available. This active use of Instagram while hiking is visible in the growth of PCT-tagged posts over a thru-hiking season. On June 11, 2019, the hashtag #PCT2019 had 32,439 posts and the hashtag #PCTClassof2019 had 5,351 posts. Four months later, on November 11, 2019, the hashtag #PCT2019 had 65,991 posts (a 103% increase) and the hashtag #PCTClassof2019 had 13,785 posts (a 158% increase).

Photos First

As a photo-dominant platform, the photograph component of each Instagram post is the most immediately prominent aspect to the viewer. Indeed, when searching posts, only the photo is at first visible. It portrays a moment the user deemed worthy of sharing with an audience. Photos tagged #PCTClassof2019 overwhelmingly feature some type of wilderness vista, with hikers frequently included both as selfies and portraits. Photos featuring hikers appear to be particularly common at mile markers, summits, notable PCT landmarks (Figure 1), and the north and south terminus of the trail. Also common are photos of “zero days” spent off trail to resupply and take a break in nearby towns.

Figure 1 – Hikers pose by the sign marking the entrance to Kennedy Meadows, denoting the completion of the desert section of the PCT. Well-known landmarks are common celebratory posts. All photos were posted between May 23, 2019, and June 13, 2019.

Figure 2 – While PCT long-distance permits are issued for single individuals, Instagram photos demonstrate high-density camping and clustering of tents. Image posted on April 15, 2019, at https://www.instagram.com/p/BwSxUmslk2S/ by user uphilladventure.

Such images can provide information representative of “on the ground” experiences and conditions, as well as other information relevant to wilderness management decisions. For example:

- A photo posted April 15, 2019 by uphilladventure (Figure 2) shows upward of 30 tents pitched in the same area, reflecting a high-density usage not communicated by the PCT’s individually issued permits.

- User thejfiles posted a photo of himself alone at the southern terminus on April 14, 2016. However, his photo of the northern terminus on September 7, 2016, shows him with six other hikers, for a total group size of seven.

- User eli.exists posted a starting photo at the southern terminus on April 6, 2018, with one person, but a photo at the northern terminus with six total people.

By contrasting the photos at the beginning of hikes to those posted at the end, wilderness managers can better establish what a thru-hiker’s experience and potential impact on wilderness resources can look like.

Perceptions of Wilderness

Accompanying each photo is a caption written by the user – a real-time, self-narration of their journey that offers a window into how they perceive the wilderness around them. Without prompting by a survey, and before time has increased the likelihood of misremembering or tinged recollection with nostalgia, users share their primary reasons for going into the wilderness and what they find there:

Figure 3 – A hiker narrates her reaction to a section of the PCT affected by wildfire. Image posted June 23, 2019, by user katheleenlovesyoga at https://www.instagram.com/p/BzDoRgslyNG/. At the time of data collection (July 31, 2019), the post had 681 likes and 33 comments.

- “I haven’t much clue as to how I ended up on the PCT this year,” wrote thekindofblue on a May 28, 2019, photo. “Here I’ve found myself a trail family, kindness, and the sheer power of nature… Somehow, it feels like the trail was always an inevitable part of me.”

Captions describe a hiker’s emotional highs and lows, their thoughts while hiking, encounters with both nature and people, feelings toward surroundings, reflections on wilderness (Figure 3), and concerns about upcoming sections of the trail.

- “Since the beginning of trail it has felt as if the only thing on everyone’s mind has been the Sierra,” wrote Ian.bertram on a June 6, 2019, post. “Due to high snow fall and recent storms the next section of trail will likely be quite the challenge, but I’m excited to explore what’s ahead.”

Also illustrated is how a wilderness experience on the PCT continues to affect thru-hikers months or even years later (Figure 4). Reflecting on his one-year anniversary of beginning a PCT thru-hike, on April 25, 2019, user crumbsontrail reposted a photo of himself at the southern terminus and captioned it:

- Happy trail anniversary to me! The memories are so vivid, so full … we can choose to take a risk, not live the way society wants us to live, and follow our heart. May it be becoming an artist, trying a different job, going back to school, leaving the country or go on a 2650 miles long hike [through] raw, wild nature.”

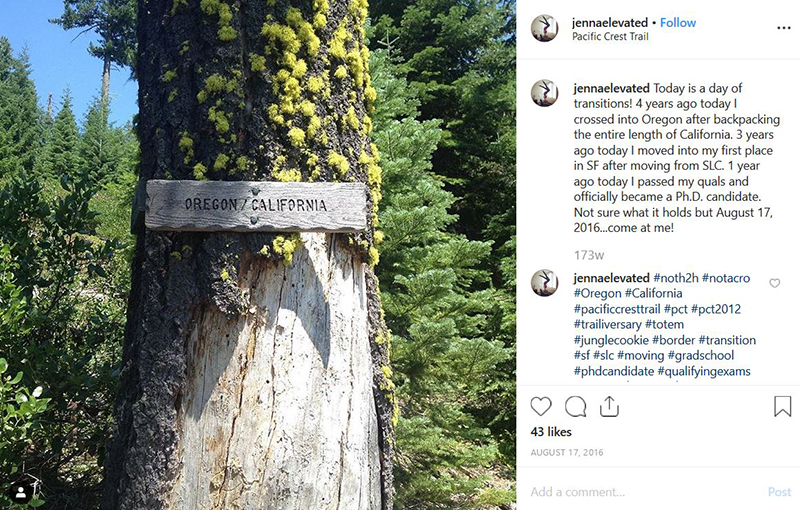

Figure 4 – Completing a thru-hike is portrayed on Instagram as a defining achievement that serves as a milestone against other life events. Image posted August 17, 2019, by user jennaelevated at https://www.instagram.com/p/BJNxxOQguqK/.

For user crumbsontrail, a thru-hike of the PCT was a chance to break away from society’s expectations about how one should live their life, a perception he continued to portray to his social media followers a year later.

Other users shared retrospective feelings of loss.

- On a November 6, 2018, post, carlsbest wrote: “After I finished the PCT, I fell into post trail depression and it was difficult for me to transition back to [off-trail] lifestyle.… Depression and lack of energy kept me from doing the things I love. I was using all my energy into work and I am exhausted. I have not had the energy I get outdoors and do what I love. Hike.

On the same post, prior PCT thru-hiker clareschmidt7 commented,

- “I worry that the more time between me and the PCT, the lower my energy and excitement about life, I’ve never felt so alive and in touch as I did on that trail.”

Other captions are primarily logistical, noting the location the photo was taken, trail conditions, and miles hiked. Thru-hikers sometimes note what encounters most detracted from their wilderness experience:

- wherethehellissteve identified the negative effects of nearby resource extraction, writing on a July 17, 2019, post, “Woke up at 4AM this morning to the sweet sounds of lumberjacks and bulldozers clearcutting the forest in the valley below our campsite.”

These types of observations provide wilderness managers with a snapshot of where management interventions may need to be most prioritized.

#Hashtags

Following each caption are hashtags, labels that allow viewers to search for specific categories of photos. Hikers tag photos with a wide array of hashtags, sometimes placing more than 30 on a single photo (Figure 5). At minimum, photos typically include a hashtag specifying the trail and year attempted. As of December 16, 2019, the hashtag #pct2014 had 3,692 posts, the hashtag #pct2016 had 35,939 posts, and the hashtag #pct2018 had 70,821 posts. This type of logistical hashtag can assist in remedying the challenge that wilderness trends at a specific place over time have been difficult to track (Dvorak et al. 2012). Tools to follow wilderness users, such as self-permitting, aerial photography, direct observation, and surveys can be imprecise, time-consuming, and expensive (Hammitt, Cole, and Monz 2015). Instagram and other social media platforms help fill these voids, allowing observation of the PCT year after year. While such a dataset will bring its own limitations – it is driven by the whims of the user, not a standardized survey, and can go back only to 2010, the year Instagram was founded – it makes assembling large sample sizes of specific cohorts of wilderness users in a specific year a rapid process.

Other hashtags identify resources being used by thru-hikers. The hashtag #withguthook indicates a user is using Guthook, a popular hiking app that provides extensive detail about the PCT, including offline maps, photos of waypoints, real-time information about trail conditions, and water availability provided by other hikers. Counting the use of this hashtag offers some insight into the frequency of digital app use for wilderness navigation.

Figure 5 – Photos are typically tagged with multiple hashtags. User paigepasquini labeled their post with 33 hashtags, including #guthookguides and #ultralight (resources used on the thru-hike), #womenwhohike and #womenwhoexplore (establishing an identity), and #dirtbagdarling (reclaiming a term of disdain as one of pride). At time of original data collection (July 23, 2019), the post had 294 likes and 10 comments.

A user’s hashtag also provides insight into how they perceives themselves and their journey. PCT photos included hashtags such as #womenwhohike, #blackgirlswhohike, #latinaswhohike, #veganthruhiker, and #plussizehiker, each claiming an identity beyond “thru-hiker.” The frequently used #hikertrash transforms the shameful perception of “trashy” into a mark of pride. Other hashtags communicate perceptions and goals of the journey of the thru-hike: #optoutside, #neverstopexploring, #adventurelife, #wanderlust, and #wildernessculture each link thru-hiking with a specific perception of how life should be lived.

Hashtags can extend the audience of PCT photos to audiences not familiar with wilderness. Alongside PCT hashtags are hashtags for seemingly unrelated topics. For example, on July 18, 2019, heparker1 used, in addition to #PCTClassof2019, the popular #dogsofinstagram label, which had 159 million posts as of August 2019. Users without knowledge of the PCT will search for an unrelated topic (dog photos) and find themselves with content about the PCT. Much of wilderness media can be self-selecting; books, articles, and Leave No Trace education consumers will likely have at least minimal awareness of wilderness. With unrelated hashtags, the potential viewing population for the posted wilderness perspectives and practices widens enormously.

Audience Perception

The final component of an Instagram post are comments left by viewers. Sometimes family and friends of the thru-hiker or sometimes strangers ask questions and provide thoughts and opinions on the depicted situation. Most frequently, comments take the form of a torrent of praise and validation of the thru-hiker. Within 14 hours of posting, akuerzdoerfer’s August 4, 2019, photo of his thru-hike completion garnered 540 likes and 39 comments, all highly positive:

- “You are a force of nature.”

- “Congratulations on such an incredible accomplishment.”

- “hell yeah!! My deepest respect!!”

This praise extends to more ordinary moments as well. ludlmama’s June 1, 2019, post, which describes struggling through a patch of bad weather, resulted in viewer comments such as:

- “You are astounding! [Heart emoji] totally crying.”

- “You are an excellent writer. This was an exhilarating read.”

- “Woaaaaaah this is an epic post and epic picture.”

In their commentary, viewers hint at their own perceptions of wilderness. On a May 31, 2019, photo by katiecarp (Figure 1, bottom right), one viewer asked if she was bringing a gun.

Solitude and Instagram

The composition of Instagram posts raises new questions for how persons interact with wilderness. The Wilderness Act directs wilderness to provide “outstanding opportunities for solitude.” What does solitude look like in the context of Instagram? Social media posts are intended to share experiences. While the user may be physically isolated, the portrayed moment is intended to include connection with, and allow commentary from, other people.

Is this solitude? Wilderness writing, painting, and photography have always shared personal wilderness experiences, but Instagram enables narration of and reaction to a wilderness journey at a speed and audience size previous artistic expressions do not. The rapidity with which Instagram posts can be created drastically shortens the time between when a hiker experiences the PCT and when they talk about it with an audience. This is particularly true of a thru-hike: the multiple-month time frame means a hiker can receive, and potentially have their experience altered by, viewers’ feedback while still in the wilderness.

Instagram has also emerged as a performance-centric platform. It is used to curate the appearance of an attractive lifestyle, often with intentional exclusion of any negative experiences (Pilar, Balcarova, and Rojik 2016; Fox and Vendemia 2016). Users who engage with it do so with a primary motivation of appearing cool and creative to those around them (Sheldon and Bryant 2016). The torrent of praise and validation heaped onto PCT photos – whether from commenters or the volume of “likes” – reflects the success of those motivations. Can the character of a wilderness experience be retained against a potentially dominant desire to cultivate an identity to share via social media? A hiker might be in physical solitude, but social media is designed to share and allow viewers to engage with the experiences of others. While depicting quests of solitude and escape from society, while tagging photos with hashtags such as #WannaBeWhereThePeopleArent, hikers join spaces where people are and bring them along on their journey into wilderness.

Inclusion of this audience in a wilderness journey can even bring financial opportunities for hikers, who can use Instagram to find sponsorship to help pay for their trip. On a March 16, 2016, post that garnered more than 1,700 likes, brandonexplores wrote that MSR would be sharing “some of the work I produced while I was out there in the wilderness for 6 months.” He went on to praise the company, writing, “couldn’t of [sic] done any of it without the support of great gear companies like @msr_gear.” When an outdoor gear company complimented their March 2016 photo, user cachebuster responded with an inquiry about whether they were seeking new gear ambassadors. Opportunities aren’t limited to outdoor gear. A June 27, 2019, photo by meredithj7 had comments from three companies (selling lip balm, jewelry, and furniture) offering to “collaborate.”

Other hikers request sponsorship directly from their viewers. To fund his 2019 thru-hike, user secondchancehiker set up a Patreon, a website that allows online “patrons” to make monthly financial donations in exchange for benefits such as exclusive social media content. As of September 15, 2019, secondchancehiker had 278 patrons making financial donations, in addition to more than 12,000 Instagram followers and 26,000 YouTube subscribers. Throughout his journey, he produced multiple types of social media targeted at financially contributing viewers, including footage of being evacuated by helicopter due to a back injury.

The PCT Association found lack of money to be one of the most frequently cited reasons a thru-hikers ends their journey (PCT Association 2019), meaning gear or financial sponsorship may be the enabler of a wilderness experience. A mutually beneficial relationship is formed: hikers earn financial support, while companies gain brand ambassadors who can increase sales by placing their products in the context of adventures in beautiful places. Many thru-hikers also have side projects of their own, generating content for audience consumption throughout their thru-hike. “Read full post by heading to [blog URL] under the “journal tab,” urged lupine_hikes on an August 30, 2019, post. “While you’re there, subscribe to the mailing list!” User sunshineconsultingllp wrote on August 5, 2019, “The following is a [sneak] peak of my next blog post (link in bio).”

Conclusion

Social media may redefine what solitude and other concepts in wilderness mean. Further implications of this trend remain to be explored, but ignoring the information provided by Instagram and other social media spaces ensures that changes will occur without active discussion. This is particularly relevant when considering the heaviest users of social media: the younger generations still developing their wilderness ethics. They will be the persons setting policies and social norms in wilderness in decades to come. If their wilderness habits include regular use of social media, excluding study of its presence and influence will neglect a large component of the wilderness experience.

Even if wilderness managers choose not to investigate Instagram or other social media platforms to inform active management decisions, they should be observing this space to understand how users are portraying wilderness experiences. In a July 25, 2019, post tagged #threesisterswilderness, user kkferb responded to upcoming use restrictions, writing:

- “I met a lot of nice people today on the trails and some talked about the limited entry/permit system which takes effect in our area in 2020.… The days of spontaneous trail adventures on many of the wilderness trails will be no longer. I will dearly miss them. I also understand the need to protect those special places negatively impacted by overuse, and sadly, abuse.”

Such responses to management action can provide insight into where more public education or outreach may be needed, or where wilderness users are dissatisfied with decisions.

With social media comes also the potential for observing joy. Contemporary philosophies of wilderness preservation often include spiritual justification, arguing wilderness allows individuals to connect with something greater than the self while cultivating respect for nature and solitude (Adams 2008; Nash and Miller 2014). It portrays wilderness as offering opportunities for personal growth through physical challenges. With the caveat that Instagram experiences are carefully curated, thus presenting their own type of bias, they also demonstrate the powerful emotional journey of the trail. On August 6, 2019, steplotus_ wrote:

- “Snoqualmie Pass, WA. BACK ON TRAIL!… Nearly a year ago I stepped up to the same trail head and unbeknown to me, it would be the last time I would hear my mom’s voice… Today, I step here with confidence. Is it because I am home? Is it because I am surrounded by trail friends who have made this process gentle and warm? How did I arrive to this space of confidence and bliss, knowing I’d be walking over the same miles I said my goodbyes to my Ma? Celebrate. Tribute. Memory. Before taking our first steps, I call dad, “I am ready. We are going to start walking!” Dad replies “okay, you know Mom is with you, right?” “I know, Dad. She’s here.” Lets do this.”

Social media changes how wilderness users share and perceive their experiences. Through their posts from the trail, they share anniversaries of sobriety, mourn destruction from wildfires, ponder gratitude and friendship, and celebrate wilderness. With social media, a new platform to examine how wilderness weaves itself into the American experience has emerged.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Kari Gunderson for valuable guidance in developing this article.

KATHRYN SUTCLIFFE, MPH, is based out of Boston, Massachusetts, and is interested in connections between mental health, social media, and the outdoors; e-mail ka.sutcliffe@gmail.com.

References

Adams, C. C. 2008. The importance of preserving wilderness conditions. In The Wilderness Debate Rages On:

Continuing the Great New Wilderness Debate, ed. M. P. Nelson and J. B. Callicott. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Byrne, M. 2014. Instagram statistics. Optical Cortext [Product Design agency]. https://opticalcortex.com/instagram-statistics/.

Dvorak, R. G., A. E. Watson, N. Christensen, W. T. Borrie, and A. Schwaller. 2012. The Boundary Waters

Canoe Area Wilderness: Examining Changes in Use, Users, and Management Challenges. Res. Pap. RMRS-RP-91. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Hammitt, W. E., D. N. Cole, and C. Monz. 2015. Monitoring Recreational Impacts. In Wildland Recreation: Ecology and Management, 3rd ed. (pp. 196–217). West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons.

Fox, J., and M. A. Vendemia. 2016. Selective self-presentation and social comparison through photographs on social networking sites. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 19(10): 593–600. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0248.

Nash, R., and C. Miller. 2014. Wilderness and the American Mind, 5th ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Pacific Crest Trail Association. 2019. Thru-hiker FAQ. https://www.pcta.org/discover-the-trail/thru-hiking-long-distance-hiking/thruhiker-faq/, accessed July 30, 2019.

Pew Research Center. 2019. Social Media Fact Sheet. http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/, accessed September 2, 2019.

Pilar, L., T. Balcarova, and S. Rojik. 2016. Farmers’ markets: Positive feelings of Instagram posts. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis 64: 2095–2100.

Sheldon, P., and K. Bryant. 2016. Instagram: Motives for its use and relationship to narcissism and contextual age. Computers in Human Behavior 58: 89–97.

US Public Law 88-577. The Wilderness Act of 1964. September 3, 1964. 78 Stat. 890.

Read Next

Of Global Concern: Reliance upon Resilience

There is no argument that the Australia bushfires are of global concern, but what may be of more concern is the lack of a greater resonance across the globe. If nature can no longer react and response to threats, then nature must rely upon us.

Wilderness Trails: Influences of Perceptions

Wilderness areas may not be perfect, and there may be some rules, but without a doubt they benefit society, and it is imperative that society can access those benefits. Trails are a perfect guide leading people to those benefits.

The Toda People: Stewards of Wilderness and Biodiversity

At a period when humankind appears to be so disconnected with nature that they assume their species can survive without respecting other forms of life, it might be pertinent to see how a traditional Toda mind is trained to interact with nature.