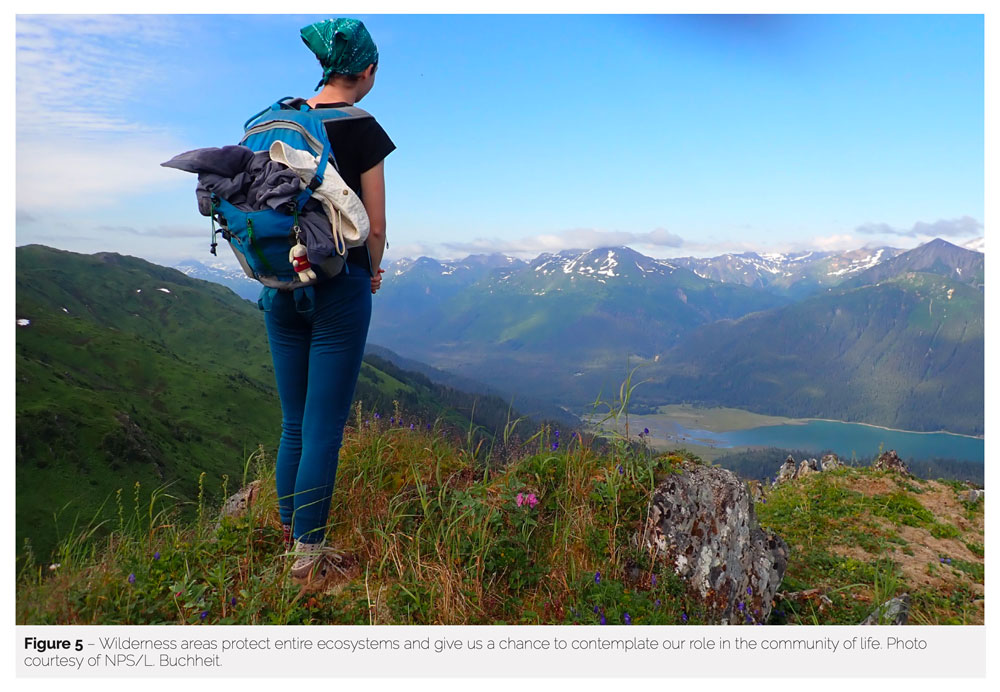

Glacier Bay Wilderness provides outstanding opportunities for enduring connections. Photo credit: NPS/Kiana Young.

Reimagining the Wilderness Concept for a Diverse America: A Case Study of Inclusive Wilderness Stewardship in Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska

by ADRIENNE LINDHOLM

Communication + Education

December 2023 | Volume 29, Number 2

“By honoring and recognizing past, current, and future connections people have to these places, and using language and images that foster a sense of belonging for all people, we will empower a new generation of stewards and will garner support for conservation.”

Glacier Bay Wilderness

Glaciers have sculpted this landscape, from the sharp brows of its mountain peaks to the deep troughs of its fjords. Even the land itself is rising as the colossal weight of ice eases off it. Here, in what is now Glacier Bay National Park, it is as if the span of time has been condensed and unfurled across the landscape. It is a place renowned and protected for its biological diversity, constant change, and opportunity for study (National Park Service [NPS] 2023).

Since its exploration by John Muir in 1879, scientists from around the world have been attracted to Glacier Bay’s living laboratory of intact ecosystems dominated by natural successional processes. Visitors continue to congregate in the warmer summer months to witness the calving of tidewater glaciers and contemplate change, resilience, and their connection to this dynamic landscape (NPS 2023).

Originally established as a national monument by presidential proclamation in 1925, the area became a national park with new land additions and designated wilderness in 1980 under the Alaska National Interest Land Conservation Act (ANILCA). Although Huna and Gunaaxoo Tlingit clans had called Glacier Bay and Dry Bay Homeland since time immemorial, little mention was made of the original inhabitants of this seemingly pristine land- scape in early documents. Early park managers may have viewed Indigenous use as irrelevant to park purposes and values or may have been entirely ignorant of the enduring connection of Tlin- git clans and their interconnectedness with Glacier Bay Homeland. Importantly, the dynamism of the park landscape and resulting successional processes essentially hid or erased evidence of long-term use and occupation of the land and waters of Glacier Bay by Tlingit clans.

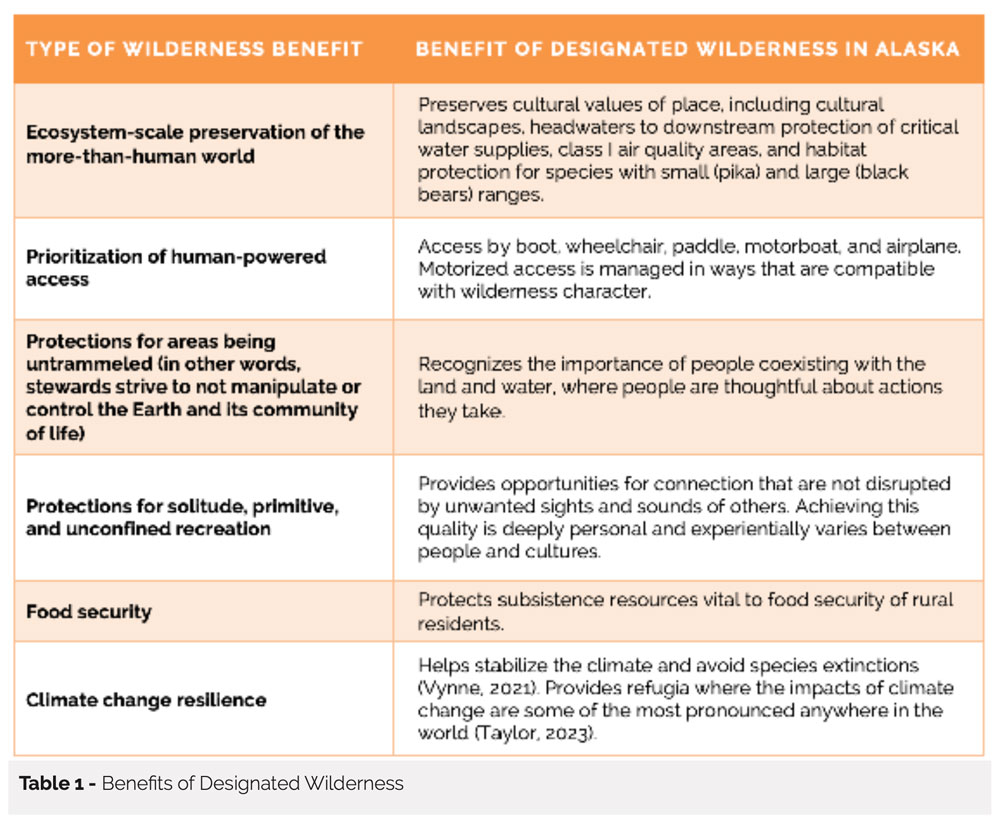

Benefits of Wilderness

The wilderness designation offers benefits that are both complementary to, and distinct from, non-wilderness lands contained within National Park Service units (NPS 2023a). The benefits of wilderness are expanded in Alaska where, in addition to many of the benefits found in the lower 48, ANILCA protects food security for rural residents (Table 1).

Glacier Bay Wilderness, like all wilderness areas, provides myriad benefits that amplify National Park Service (NPS) unit protections, such as spaces for mental and physical health, spaces for growing connections with loved ones, tourism for local and regional economies, and protections for ecosystem services.

Criticisms of Wilderness

Given the long list of benefits of the federal wilderness designation, why, then, does there continue to be opposition to wilderness, and how can federal agencies like the NPS address it? Though there will always be those who favor motorized recreation and extractive industry over wilderness preservation, this article focuses on criticisms related to diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility.

US federally designated wilderness is commonly conflated with the concept of wilderness as defined by popular culture, which oftentimes perpetuates a myth that America was sparsely populated prior to 1492, and its ecosystems were virtually unmodified by human actions. This framing, especially when considering the relationship between wilderness and Indigenous lifeways, is highly problematic.

Wilderness has come under attack partly because its early champions failed to acknowledge the profound connection Indigenous People had, and continue to have, to these lands. Concerns relate to land dispossession, the fact that Indigenous People both occupied and shaped these unique landscapes, real and perceived lack of sincerity when federal agencies conduct legally required Tribal consultation, and agencies’ slow embrace of co-stewardship conservation models. Wilderness has been criticized as racist, exclusive, a place with unreasonable restrictions on use, a place that erases culture and human history, and a place where only adventure enthusiasts belong.

The NPS in Alaska, and Glacier Bay National Park specifically, have recognized the need for a more expansive wilderness stewardship model, a way to maximize the benefits of the wilderness designation for a broader range of people, and a way to perpetuate the values, uses, and connections people have had with these places since time before record.

The NPS in Alaska is reimagining wilderness and addressing some of the criticisms and misconceptions around wilderness because (1) those who manage and benefit from wilderness areas have a responsibility to acknowledge the traumatic history of establishing conservation lands in this country, (2) public land designation should serve diverse sectors of the American public, and (3) growing support for conservation is necessary for our own survival. There is a future that we are all a part of that is in trouble due to climate change, adverse impacts from resource extraction, and the hubris and indifference that epitomize the relationship that many people have toward the environment. Humankind, and virtually all nonhuman species on the planet—all of which are inherently valuable— are in peril. To garner support for conservation, we need to shift the national dialogue around wilderness, the land designation that offers the highest level of protection for the environment.

NPS Wilderness Reimagined

Sideboards for Reimagining the Wilderness Concept

The Wilderness Act of 1964, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) of 1980, and NPS policy provide clear sideboards for how the agency can work to make wilderness more inclusive. While the definition of “wilderness” from the 1964 Wilderness Act and wilderness stewardship policy direction have not changed, NPS staff can use plain language to talk about wilderness character and wilderness values in ways that resonate more broadly. They can also talk about the history of wilderness in ways that honor and recognize many perspectives and points of view. They can elevate stories and experiences of underrepresented demographics and select images that are more inclusive than those that have been portrayed in the past. NPS employees can engage and partner with Tribes in meaningful ways. They can change how staff are trained and how they recruit the next generation of wilderness stewards. The NPS is not replacing Wilderness Act language or national policy but rather is broadening how they are implemented.

The Wilderness Act and ANILCA Support a More Inclusive Wilderness Concept

While some point to language in the Wilderness Act feeling offensive and exclusive, there is sufficient wording in both the Wilderness Act and ANILCA to support a more inclusive implementation of the wilderness concept.

The Wilderness Act was a direct response to widespread environmental destruction and the hubris of dominant Western culture—that humans are entitled to dominate and master our environment. Some misconstrue language in the Wilderness Act to imply that to protect the environment, the government must banish people from it. Rather than prohibiting people, the Wilderness Act prescribes a specific type of relationship that is compatible with environmental protection. The Wilderness Act interjects a necessary level of humility into the dominant perspective of how people relate to land.

Section 2(a) of the Wilderness Act states that Wilderness areas “shall be administered for the use and enjoyment of the American people in such manner as will leave them unimpaired for future use and enjoyment as wilderness.”

Specific public purposes (or uses) of wilderness are described in the Wilderness Act, Section 4b: “Except as otherwise provided in this Act, wilderness areas shall be devoted to the public purposes of recreational, scenic, scientific, educational, conservation, and historical use.” This use set uniquely positions wilderness as an interdisciplinary concept and place that spans experiential, knowledge-growing, and preservation interests.

Special provisions are included for livestock grazing, aircraft use, motorboat use, commercial services, and others. The Wilderness Act certainly envisioned people on the land; it defined the relationship between people and the land with sideboards to protect the sanctity of nonhuman life and processes. Additionally, 2006 NPS Management Policies support access for traditionally associated peoples and encourage cooperative conservation of resources.

In Alaska, all NPS wilderness was designated through ANILCA. ANILCA assures access to and use of traditional homelands by providing for the continuation of subsistence activities; reasonable access to subsistence resources; a preference for subsistence harvest over other consumptive uses; and for development, retention, and use of cabins and other structures to support subsistence uses (Figure 1). ANILCA also allows certain types of motorized access for nonsubsistence purposes, as well as the potential to use and maintain cabins and other structures under certain circumstances (Figure 2).

Combined, the Wilderness Act and ANILCA allow us to imagine myriad ways people might value spaces we now call wilderness. Over the last several years, NPS managers in Alaska have been working to create a cultural shift within the agency to think about wilderness not as a place devoid of people but instead as a place where people can find a diversity of meaningful connections with the land. Within Alaska, Glacier Bay has been leading the way by operationalizing the following strategies.

Present a Holistic and Honest Narrative around Wilderness

To address some of the criticisms of the Wilderness Act, Alaska parks are beginning to acknowledge the role that conservation has played in Indigenous land dispossession and are presenting factual information about the variety of ways people can connect to wilderness.

To help change misinformed narratives around wilderness lands, we now convey the following themes in our communications:

- Wilderness stewardship builds upon the legacy of shared connections between people and the land.

- Homelands of Indigenous peoples that are now also recognized as wilderness are the culmination of thousands of years of Indigenous land stewardship.

- People belong in wilderness and can find many ways to use and value wilderness lands and waters.

Changing the Wilderness Narrative at Glacier Bay National Park

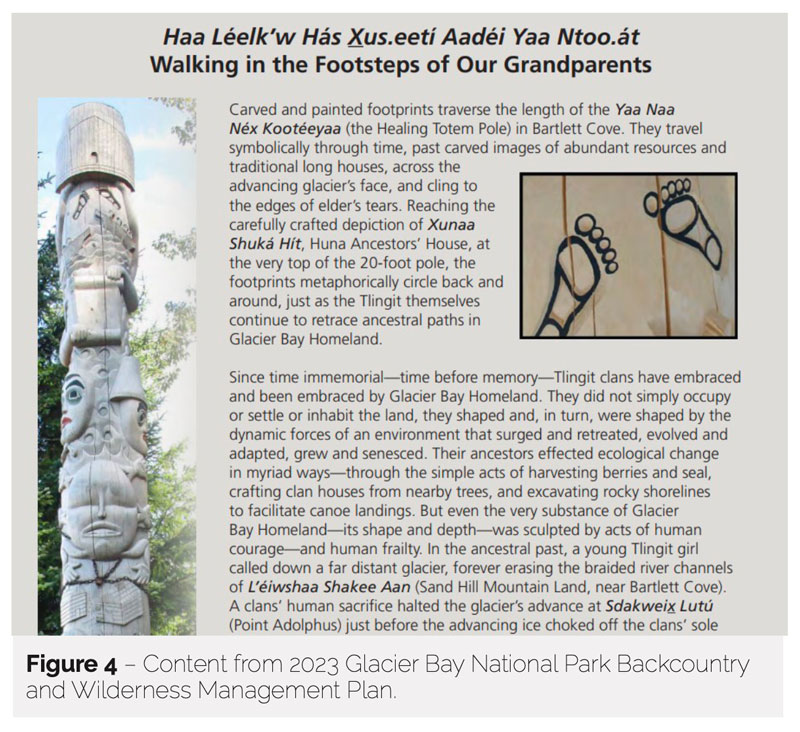

In 2018, Glacier Bay National Park signaled that it was beginning to honor its uncomfortable history through the carving of the Healing Totem Pole that stands at the head of the public dock in Glacier Bay National Park. Designed by tribal elders, culture bearers, artists, and National Park Service staff, it depicts the Huna Tlingit’s tragic migration from Glacier Bay Homeland, a painful period of alienation, and more recent collaborative efforts between the tribe and the NPS. The Healing Totem Pole was specifically designed not only to relate the difficult history between NPS and the Huna Tlingit but also to relay the history of people working to overcome past hurts and heal.

One step forward on the reconciliation jour- ney occurred several years ago when staff at Glacier Bay National Park began collaborating with tribes to shift the culture around wilder- ness stewardship. The wilderness character of Glacier Bay National Park is now defined, in part, by the sustained connection between past, present, and future generations of Tlingit and the lands and waters they call Homeland. The Tlingit have sustained themselves in Glacier Bay for centuries, and as the glaciers, rivers, and nonhuman life have advanced and receded through Homeland, so have the clans and Tlingit ancestors. Tlingit interactions with Homeland have shaped the ecology of the area for countless generations through simple acts such as harvesting berries, salmon, and gull eggs and through more complex meta- physical and spiritual processes as well. The park began to develop management plans that recognize Homeland values, and they initiated specific projects that actively engage those values.

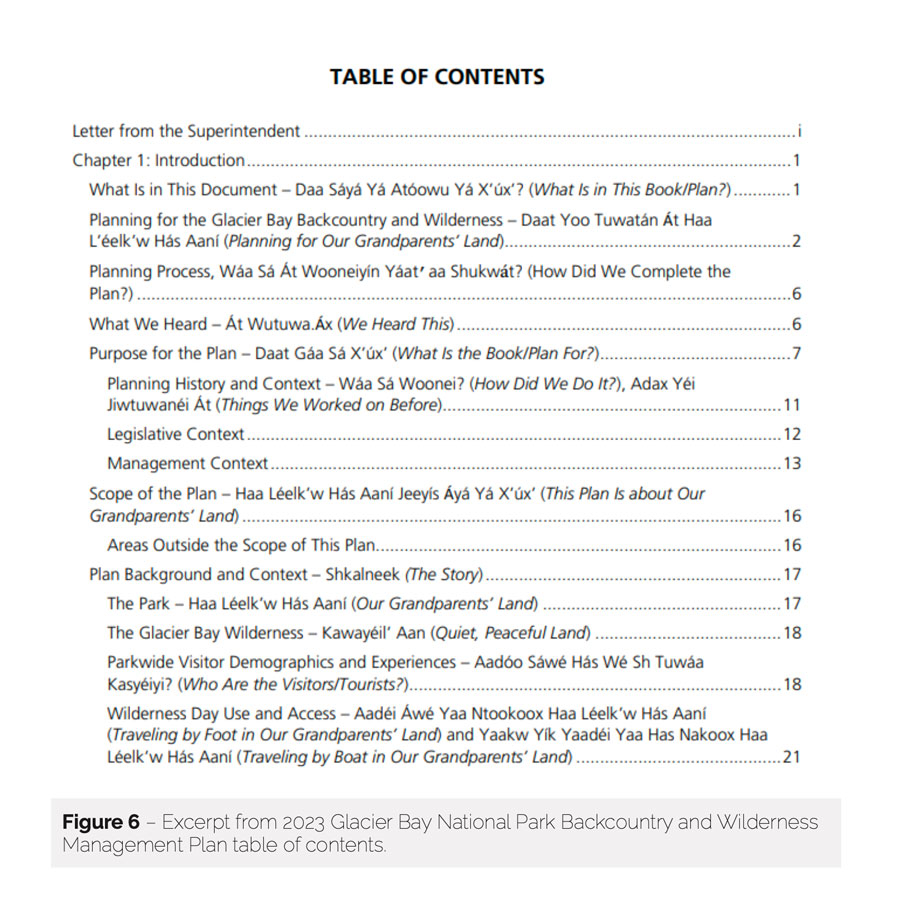

Glacier Bay’s 2023 Backcountry and Wilderness Management Plan was informed by ongoing, informal and formal government-to-government consultation with the Hoonah Indian Association and the Yakutat Tlingit Tribe, representing the original people and stewards of Glacier Bay. The NPS collaborated with both Tribes to ensure that the plan addressed longstanding tribal priorities, advanced challenging conversations about Homeland issues, and established a clear pathway for collaboratively resolving challenging issues (access, traditional fishing and hunting, land acknowledgment protocol).

Park planning documents underscore the themes listed above. For example, the following excerpt from the plan helps change the narrative that people have never been in Wilderness and don’t belong: “Tlingit ancestors whose spirits remain in Homeland, are not visitors but rather residents of the Glacier Bay Wilderness. Their presence in Homeland is recognized and honored on every trip to Homeland. For the Tlingit, a return to Homeland is an opportunity to be in the presence of those who have gone before and to engage with the landscape in the same way that ancestors engaged.”

Shared Values

Alaska park managers collaborated with Indigenous and other partners to identify shared values and then built content and collaborations from there. This list of values is generally shared between traditional Indigenous beliefs and the values that underpin the Wilderness Act:

- Clean air and clean water

- Humans are part of nature

- Sense of connection and belonging

- Responsibility

- Reciprocity

- Sense of restraint as opposed to limitless growth/capitalism/materialism

- Humility as opposed to the dominant belief that science and technology can solve all our problems

Glacier Bay National Park discusses this overlap in web page content: “Indigenous perspectives about traditional Homeland have much in common with the aspirations of the Wilderness Act. Both embrace the interrelatedness of humans and the larger community of life; the need for humility, respect, and restraint in relating to the natural world; the need to think forward to future generations (Haa yatx’í jeeyis áyá; for our children); and the value of meaningful personal connection to place.”

Honor a Variety of Worldviews and Connections

In Glacier Bay’s 2023 Backcountry and Wilderness Management Plan, Tribal perspectives and cultural information are presented as substantive content. In addition to highlighting areas of overlap between Indigenous and Western worldviews, the planning process also created space for situations in which the two worldviews do not align.

This excerpt from the plan talks about how Homeland is not free from human control but rather in an intimate and balanced relationship with it (Figure 4). This is a different perspective than the worldview described in the federal Wilderness definition, which considers Wilderness as a place free from human control and manipulation. The park recognizes the fact that both worldviews can exist simultaneously.

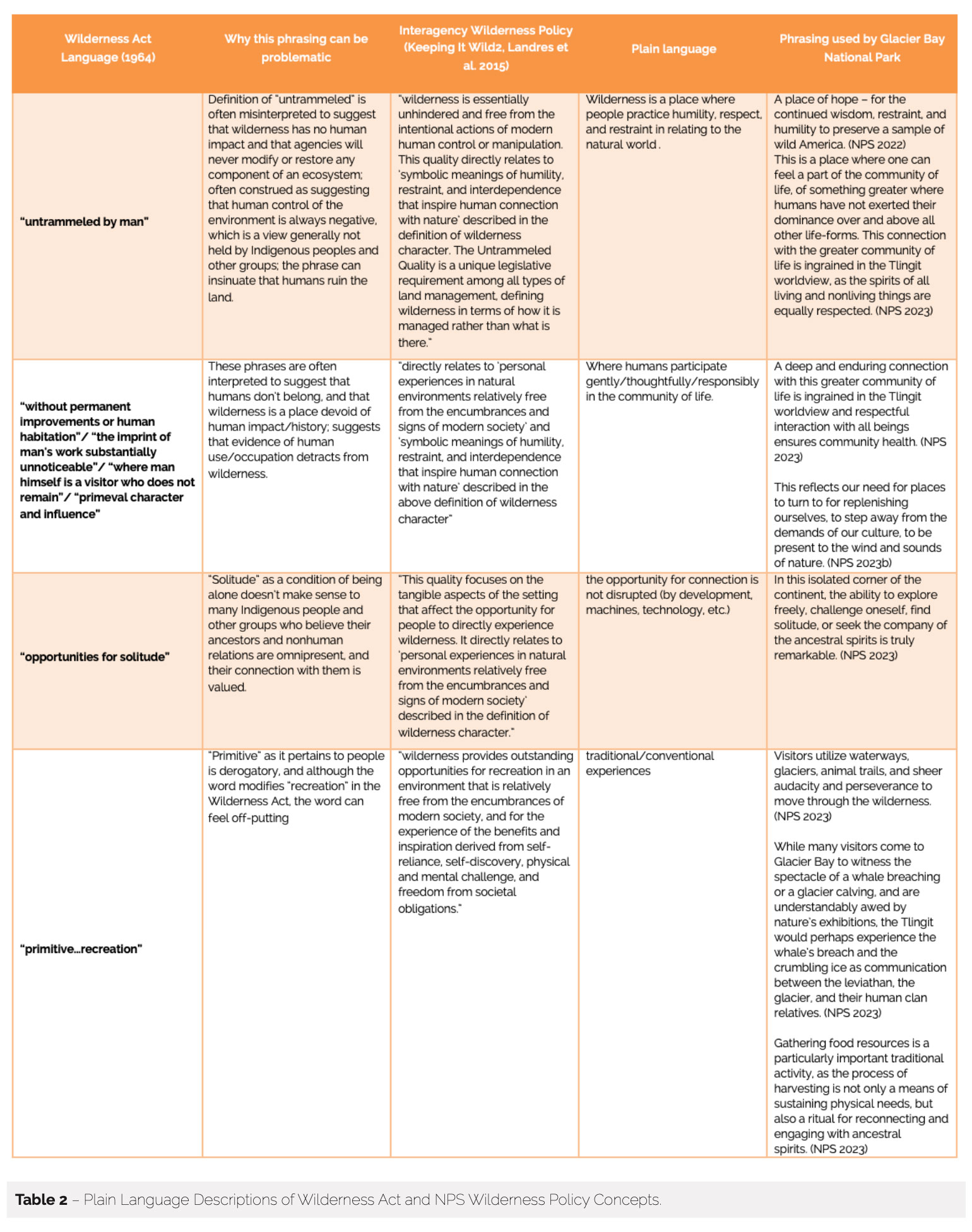

Use Plain Language in Describing Wilderness Act Concepts

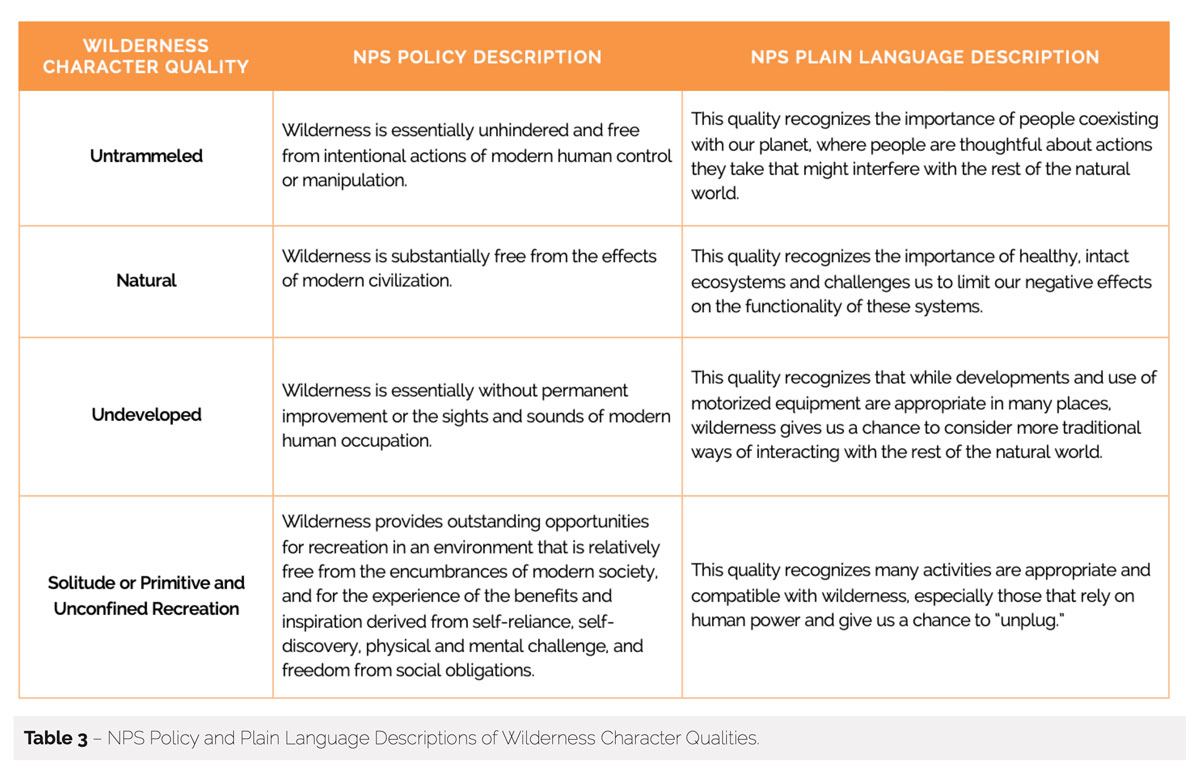

The Wilderness Act contains a definition of wilderness, which can feel confusing and exclu- sionary to some people. Language in Table 2, below, expounds upon phrases in the Wilderness Act to better recognize wilderness as inhabited spaces, homelands, and cultural or community places of value and connection. Plain language phrasing underscores the spirit of the act, which is about protecting special places from pollution and permanent industrial development, and that implores us to be thoughtful and mindful of our relationship with our surroundings.

These additional descriptions allow for broader interpretation of terms while remaining within the sideboards of existing law and policy. For example, “opportunities for solitude” is a quality of wilderness character. Many groups affiliated with the dominant culture associate solitude with an absence of other people. Many Indigenous groups believe everything on the land is animate, a relative, and that spirits of ancestors are always present. A person could never be “alone.” What matters very much is to be able to honor the connections with nonhuman relatives and human ancestors. These two worldviews do not need to be incompatible. It is reasonable that solitude can relate to both and that the NPS can manage wilderness to provide opportunities for people to experience (1) the state of being alone and (2) feeling connected to a place without having that connection violated. These are different, and compatible, interpretations of solitude.

Similarly, the Wilderness Act phrase “untrammeled by man” is often misinterpreted to suggest that agencies will never modify or restore any component of an ecosystem, and it can give the impression that humans ruin the land. According to national policy (Landres et al. 2015), the untrammeled quality addresses actions that managers take today (not in the past prior to wilderness designation) where the land manager had an opportunity to exercise restraint. It’s a measure of how much restraint and respect we use in our stewardship. This quality of wilderness character is often touted by Western conservationists as the thing that sets wilderness apart from other land designations, and it is viewed by many as the soul of the Wilderness Act. The value of living in good relationship with the land is simultaneously paramount to most Indigenous cultures, who view themselves as interconnected and kin to the nonhuman world. The Wilderness Act injects a necessary level of humility into the dominant perspective of how people relate to land. It moves the Western view closer to that of Indigenous peoples. Wilderness is a place where worldviews sometimes come together. Modernized plain language can help bridge that gap.

Use Inclusive Wilderness Language

To increase the likelihood that wilderness stewardship concepts will resonate with the widest demographic possible, wilderness stewards can use inclusive language when describing wilderness character qualities and elements of stewardship such as planning and monitoring.

One strategy Glacier Bay National Park employed in their 2023 Backcountry and Wilderness Management Plan was to collaborate with tribes to “Indigenize” planning language. Tlingit language elements encourage the public to think about the park and the plan through the worldview of those who consider Glacier Bay National Park as Homeland. This exercise also transformed bureaucratic language and made it more accessible to people outside the government.

The park’s tribal liaison took Western headings and phrases such as “scope of the plan” and “camper drop-off locations” and converted them into more approachable language such as “what’s in this book” and “where the boat stops.” She translated the phrases into Tlingit and then consulted with elders and a younger fluent speaker for assistance with orthography.

The park also avoided using descriptors such as “pristine” or “untouched” (words that do not appear in the Wilderness Act) to demonstrate that it recognizes the longstanding and ongoing role of people and their connection to lands we now manage as wilderness.

Alaska park staff have also found it helpful to use plain language when speaking about the qualities of wilderness character. Table 3 shows the definitions of the qualities of wilderness character per national policy (Landres et al 2015) alongside complementary descriptions of each quality. When agency staff use these in conjunction, they are more likely to reach a broader audience.

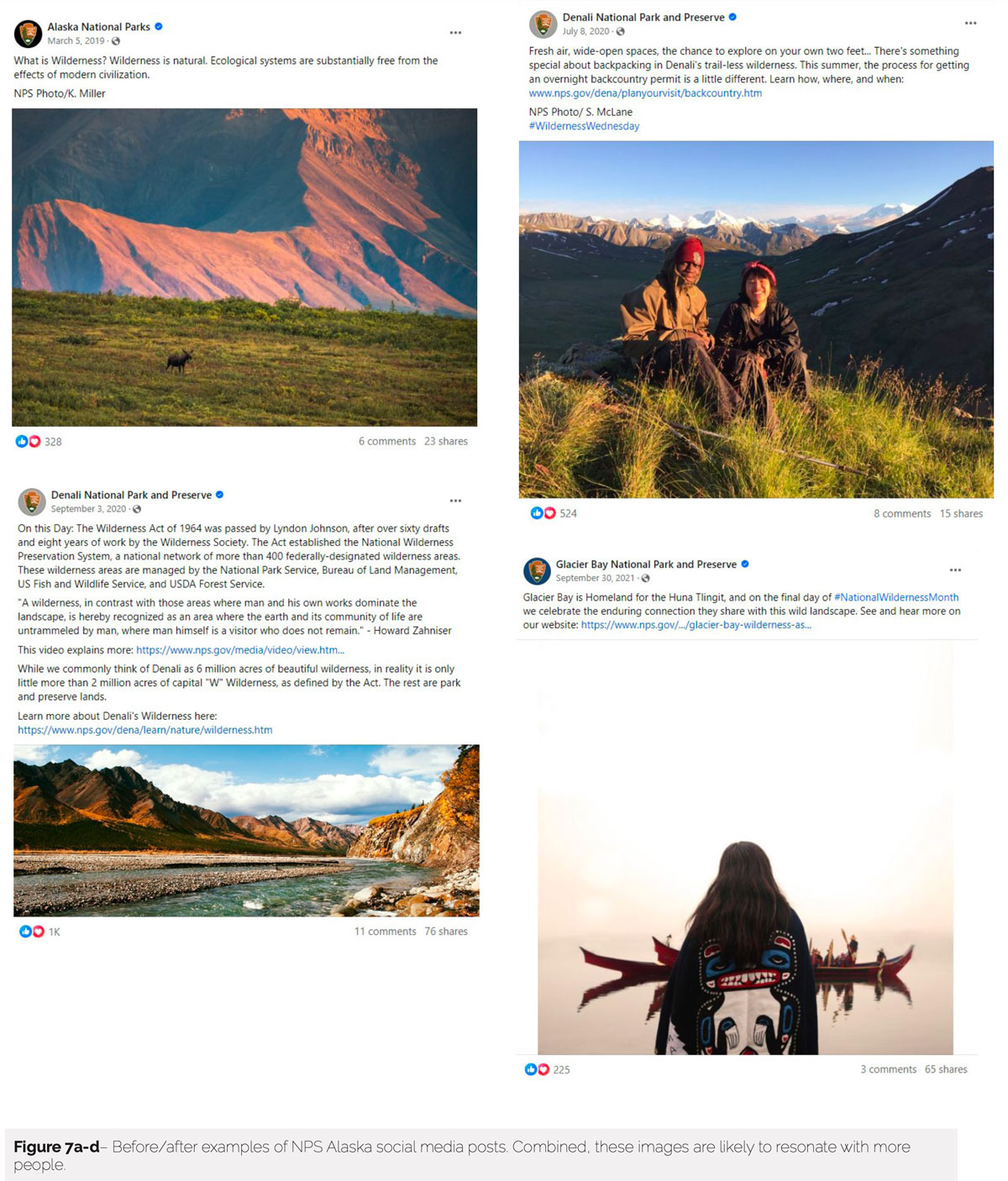

Promoting Inclusion through Digital Media and Diverse Images

In addition to using inclusive language, the Alaska national parks are taking a hard look at web content and other digital media related to wilderness and are considering what messages we are conveying through the images we show.

Several years ago, the NPS Alaska Region looked through a year of social media images related to wilderness. They were primarily pretty landscapes. We were hard-pressed to find people in the images, and when we did, it was usually a young, able-bodied white person, often solitary or with a partner. That is a perfectly acceptable image to show if it is not the only type of image depicted. Since then, the agency has been co-creating social media posts with appropri- ate groups and promoting images of wilderness that include different people (e.g., race, gender, body type, etc.), who have different abilities, who participate in different group sizes, and who connect with these places in a variety of ways.

Educating NPS Staff with New Inclusive Wilderness Training Materials

The NPS Alaska Region recently created new wilderness training curriculum for park staff that emphasizes inclusive messaging and an invitation to consider the topic of wilderness from multiple perspectives. The Alaska National Parklands Wilderness Training is an entry-level work- book with facilitated activities that is intended to introduce the wilderness concept and basic principles of wilderness stewardship. The primary purpose of the training is to promote a deeper understanding of wilderness and the evolving interpretations of wilderness that reflect the needs of a present-day multicultural America.

Expanding our thinking around Wilderness Act concepts, utilizing inclusive messaging, conveying diverse images in digital media, and training NPS staff in these concepts is laying the groundwork for changing the culture of wilderness stewardship and influencing the national nar- rative around what wilderness is and how it can benefit everyone.

Conclusion

The continued relationship of the Huna Tlingit with their Homeland is as much a part of the wil- derness character of Glacier Bay as the glaciers, bears, and the opportunity for an unconstrained experience. As the 2023 Glacier Bay Backcountry and Wilderness Management Plan strives to protect the landscape as intact Homeland and help perpetuate connections between the Glacier Bay Wilderness and traditionally associated people, most Alaska parks are also embrac- ing a new, more inclusive paradigm in their stewardship. In the years to come, we can look forward to additional examples of operationalizing an inclusive wilderness concept that honors and elevates the roles of Indigenous people, addresses some of the harmful misconceptions of wilderness, and promotes stewardship that includes a range of values and connections people have with the land.

By honoring and recognizing past, current, and future connections people have to these places, and using language and images that foster a sense of belonging for all people, we will empower a new generation of stewards and will garner support for conservation. The NPS acknowledges the uncomfortable truths of conservation while simultaneously honoring and promoting the myriad values of the wilderness designation.

There is a future we are facing together, and that future is in trouble—the climate crisis, harmful effects from resource extraction, and diminishing sense of community and connection to place, to name a few. To have a healthy environment for human and nonhuman life, we are going to need a lot of different ways of caring for the land. I submit that the federal wilderness designa- tion, interpreted inclusively moving forward, is a critical part of the solution. Leveraging the environmental protections that the wilderness designation affords, we can mitigate some of the effects of climate change, live in places that provide us with deep connections, and protect air and water that we all need to survive.

Doing away with the wilderness designation, as some propose, would not help correct the facts of history, would not help strengthen connections between excluded groups and natural areas, and would not resolve past injustices, promote healing and reconciliation, or enhance conservation. Instead, reimagining the existing system while creating alternative systems will move us forward to a brighter shared future.

Our multicultural society needs wilderness now more than ever.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to current and former National Park Service employees at Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve who contributed content and/or provided review, especially Mary Beth Moss, Sara Doyle, Philip Hooge, Laura Buchheit, and Barbara Miranda. Additional review was provided by Sarah Creachbaum, Grant Hilderbrand, Peter Christian, and Erin Drake. Thank you to all the Tribal, NGO, and other entities whose leadership on inclusion and equity in the outdoors has informed our work.

About the Authors

ADRIENNE LINDHOLM has worked for the National Park Service in Alaska since 2000. She oversees the Wilderness Stewardship Program; email: Adrienne_Lindholm@nps.gov.

References

National Park Service. 2022, July 13. What’s so special about Glacier Bay? Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Retrieved May 5, 2023, from What’s So Special About Glacier Bay? Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov).

National Park Service. 2023, April. Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve wilderness character narrative. In Glacier Bay Wilderness: Building Blocks for Wilderness Stewardship. Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. On file at NPS Alaska Regional Office.

National Park Service. 2023a, April 12. Why is federal wilderness important? National Park Service.Retrieved May 25, 2023, from WHY IS FEDERAL WILDERNESS IMPORTANT? Resource Brief (nps.gov).

National Park Service. 2023b, March 2. Glacier Bay Wilderness. Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from Glacier Bay Wilderness – Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov).

Taylor, J. J. et al. 2023. Wilderness and Climate Change. The Future of Wilderness Research: A 10-Year Wilderness Science Strategic Plan for the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute. International Journal of Wilderness 29(1): 50-73.

Vynne C., E. Dovichin, N. Fresco, N. Dawson, A. Joshi, B. E. Law, K. Lertzman, S. Rupp, F. Schmiegelow, and E. J. Trammell. 2021. The Importance of Alaska for Climate Stabilization, Resilience, and Biodiversity Conservation. Front. For. Glob. Change 4:701277.

Wilderness Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 88-577, 78 Stat. 890 (Sept. 3, 1964).

Read Next

Reflections on Wilderness 60 Years after the Civil Rights and Wilderness Acts

America’s dominant narrative of the origin of a beloved wilder- ness often centers Aldo Leopold in a heroic fight at the turn of the century against rapid industrialization that occurred at the expense of nature.

Removing the Wilderness Illusion: Emerging Professionals Explore Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in Wilderness

From the eyes of four emerging professionals in land management come four different wilderness stories.

Medicine Fish Is Leading the Way to Heal, Build, and Inspire Menominee Youth through the Wild and Scenic Wolf River: An interview with Bryant Waupoose Jr., Founder of Medicine Fish

From a bird’s eye view, the Menominee Reservation is a forested oasis in sharp relief from neighboring landscapes of dairy farms spanning northeastern Wisconsin.