Science & Research

December 2017 | Volume 23, Number 2

by DENIELLE PERRY

PEER REVIEWED

Abstract: A changing climate and increasing societal demands on water resources make river conservation urgent. The US Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (WSRA) provides a flexible policy framework ready to protect the nation’s rivers. However, the small fraction of overall protected river miles suggests forces are restraining the flow of new designations into the system. Taking an ecosystem-based approach to adaptation can serve to garner support from stakeholders and decision makers otherwise reluctant to limit water resource development. Thus, framing the “outstandingly remarkable values” (ORVs) of Wild and Scenic Rivers as ecosystem services positions the policy in relevant water resource management terms, illustrates benefits conservation provides to society, and may increase application of the WSRA for river conservation. Moreover, using a standardized ecoregion framework would address the complexity of interjurisdictional management of the national system by providing consistency in ORV identification and management, thus fostering a holistic comprehensive river conservation system. Examining the WSR distribution through the Environmental Protection Agency’s Level III Ecoregion framework sheds light on areas ripe for conservation expansion. Together, this reframing could aid in the increased application of conservation policy for ecosystem-based adaptation for river resources.

Rivers are in urgent need of increased protection as growing societal demands and climate change add pressures on water resources, exacerbating already troubled freshwater ecosystems (Strayer and Dudgeon 2010; Vörösmarty et al. 2010). Protection policies are recommended for contending with more frequent and intense floods and droughts, along with increasing resilience for species, forests, and agricultural areas (Strayer and Dudgeon 2010; Thompson 2015). Ecosystem-based adaptation measures are providing low-cost win-win solutions for adaptation that complement or even substitute for costlier hard infrastructure investments (Munang et al. 2013). Expanding and improving upon conservation policies the state already has in place may facilitate such adaptation policies (Parenti 2015). The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (WSRA) is one such policy.

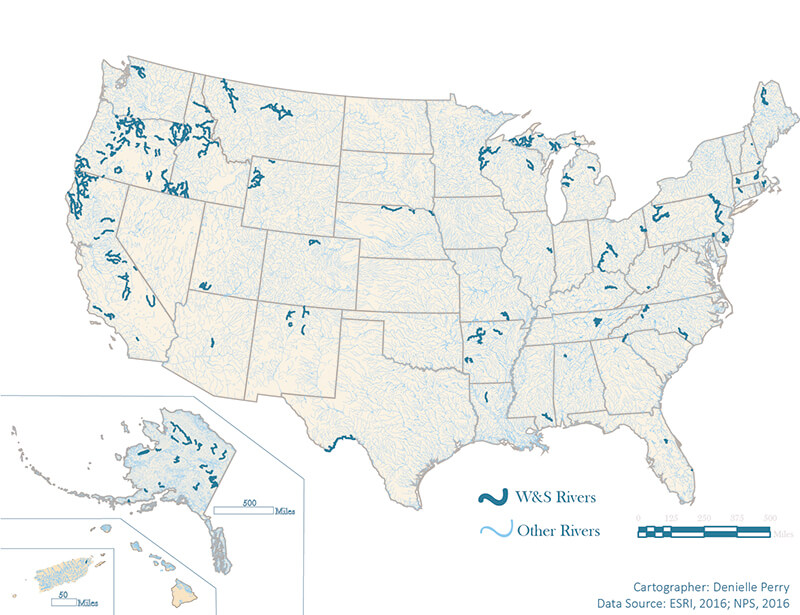

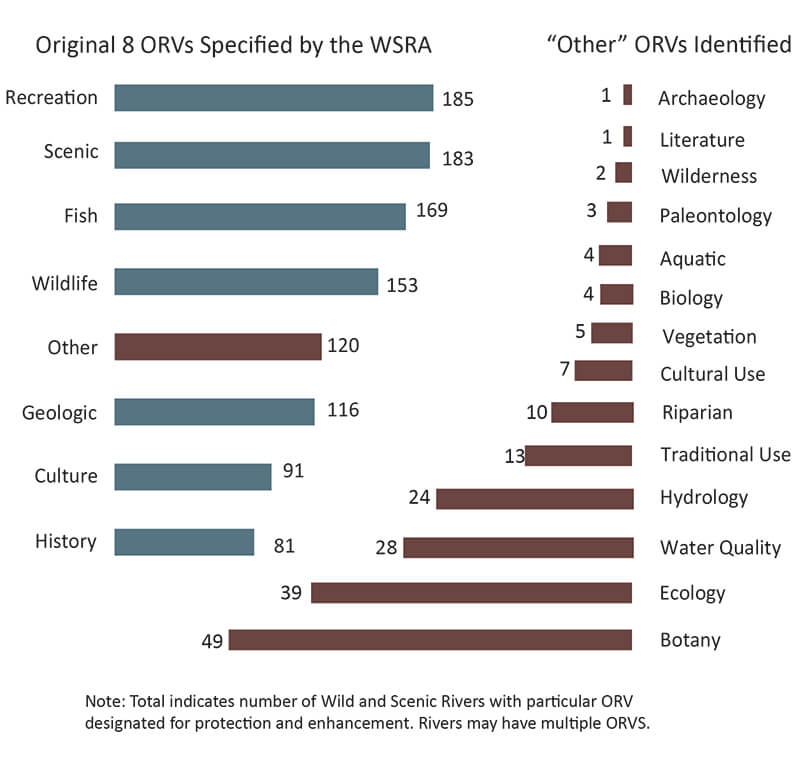

Carefully crafted to incorporate a complex interjurisdictional landscape of regionally distinct water rights and land tenure patterns, the WSRA was designed to protect and enhance the free- flowing nature, water quality, and outstandingly remarkable values (ORVs) of rivers across the US territory. The eight specified ORVs include recreation, scenic, fish, wildlife, culture, geologic, historic, and other similar values. This policy was meant to complement a heretofore national policy of water resources development centered on dams and diversions. The visionary WSRA, intended to “fulfill other vital national conservation purposes,” was flexibly designed for broad application to achieve a national river conservation system (WSR n.d.). Yet in 2017, designations total only 208, protecting just 12,733.5 miles (20,493 km). As Figure 1 illustrates, these miles comprise a mere fraction of a percent of the more than 3.5 million (5.6 million km) river miles stretching out over more than 250,000 rivers (NOAA 2017).

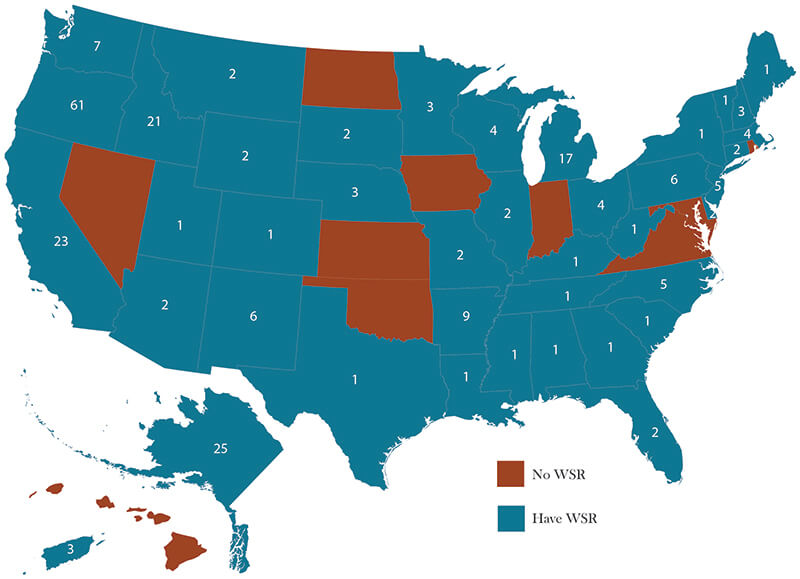

The uneven distribution of overall protected river miles across 40 states and Puerto Rico (see Figure 2) suggests application of the WSRA is complicated by both internal and external forces. Consequently, applying a policy of ecosystem-based adaptation depends on knowing what factors influence WSRA implementation. This article employed a mixed-methods analysis to reveal that a lack of standardized guidelines for determining a “region of comparison” limits the scope of the policy to provide a holistic national river conservation system. Moreover, the descriptive language of the policy’s conservation objective lacks relevance for many stakeholders. Thus, standardizing region of comparison models and reframing ORVs as ecosystem services may advance policy objectives.

Methodology

The study’s mixed-methods approach consisted of three distinct research phases. First, spatial and temporal analyses were conducted for a GIS database composed of datasets related to the national system. Datasets included designated rivers and their corresponding ORVs; the Nationwide Rivers Inventory; the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Level III Ecoregions; federal jurisdictional boundaries for land management agencies, states, and territories; and political party affiliations for legislative and executive office terms. These data were analyzed with ArcMap and Excel software.

The second phase consisted of discourse analysis of historical documents procured from the LBJ Presidential Library and the National Archives at Denver. Next, semistructured interviews were conducted with personnel attendants to the WSRA from each distinct region of the four federal land management agencies (n = 34) and two national river conservation organizations (American Rivers and American Whitewater [n = 12]), as well as associated technical experts (n = 4). Questions centered on their role in river conservation and the governance of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. In accord with grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss 1967), the interviews and archival data were coded using NVivo QDA software to break up the data, revealing six broad categories of factors influencing the landscape of the national system, namely environmental values/ideologies, location, policy, stakeholders, capacity, and science.

Protecting and Enhancing ORVs: Challenges Across Regions

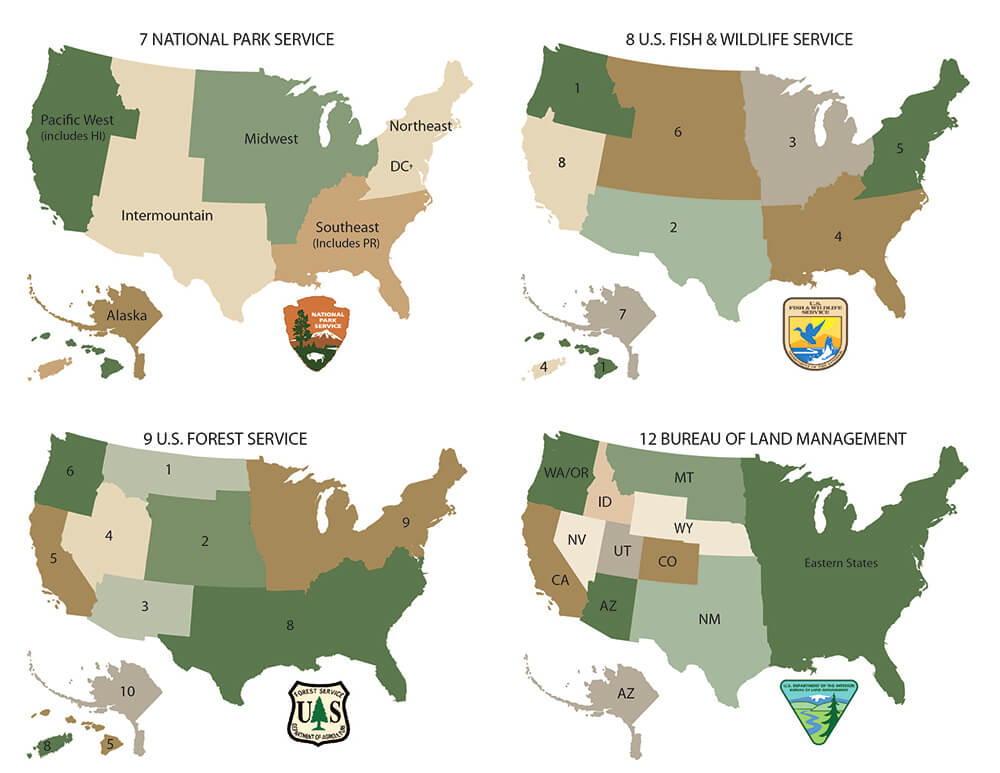

Section 5(d)(1) of the WSRA directs the US Forest Service (USFS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM), National Park Service (NPS), and the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to identify, evaluate, and recommend rivers for potential inclusion in the national system. Agencies may propose legislation for consideration by the federal administration, although they may not actively advocate for designations. To be deemed eligible for inclusion in the national system, a river must be free-flowing and in possession of at least one ORV. Among the criteria for determining ORVs is the nature of its contribution “to the functioning of the river ecosystem” (Diedrich and Thomas 1999, p. 13). As Wild and Scenic Rivers are intended to be unique unto the nation and their region, a Region of Comparison (hereinafter ROC) or the “geographic area of consideration for each outstandingly remarkable value that will serve as the basis for meaningful comparative analysis” must be established to assess the unique qualities of river resources (USFS 2015, p. 4). However, no standardized guidelines exist for defining a ROC. Instead the policy affords agency and personnel discretion in the process, which may thwart ORV recognition and protection.

Regional eligibility of ORVs can be determined in several ways, including by comparison across ecoregions. However, ecoregion frameworks are inconsistent throughout the interagency system and across the intra-agency boundaries depicted in Figure 3. For instance, personnel from distinct BLM regions revealed that in one region The Nature Conservancy (TNC) ecoregion model was applied whereas the USGS physiographic provinces were utilized in another. One agent stated “there’s many ways to look at regions and how you make that split as far as trying to determine regionally significant. It all comes down to interpretation.” Fundamentally, the selection pro- cess is a question of regionalization, a problematic exercise due to the subjective nature of selecting region- defining features (Murphy 2013; Walker 2003). For wild and scenic rivers, the process is complicated by a lack of standardized guidelines as each agency either adopts a model or uses proprietary models based on resource management priorities. What may be a significant conservation goal for one agency in a particular region may not translate to the next (Omernik and Griffith 2014). Thus, advancing a holistic national river conservation policy calls for a standardized, non- partisan ROC model.

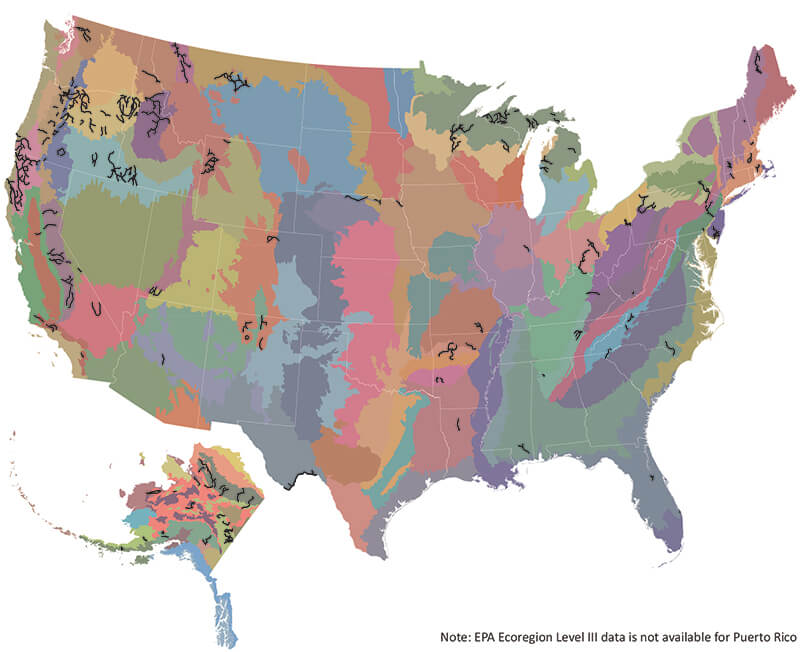

This objective is particularly important because freshwater ecosystems have high rates of endemism, or the presence of unique populations of species found nowhere else on the planet (Abell et al. 2008). Endemism makes freshwater ecosystems susceptible to high rates of extinction as impaired and modified rivers lead to local extirpations or extinctions. The risk of such extinctions is rising with climate change and population growth (Strayer and Dudgeon 2010). Therefore, protecting a suite of rivers from each ecoregion would advance the act’s purpose of fulfilling today’s vital conservation needs. The EPA’s Level III Ecoregion model is argu- ably the most appropriate framework for such a purpose. Chosen for its longevity, level of refinement over 30 years, and independence from land agency agendas, this framework addresses core regionalization challenges (Omernik and Griffith 2014).

Spatial analysis of designated rivers using this model reveals in Figure 4 an uneven distribution of ecoregion representation within the national system. For instance, a single ecoregion contains 24 protected rivers while 35 ecoregions contain none. The question then remains, what other factors are driving this uneven distribution?

Reframing ORVs as Ecosystem Services

Interview participants attributed challenges to designate more rivers to several factors. First, a lack of political will is grounded in perceptions that conservation curtails economic growth by limiting water resources development and entrenching fiscal resources. In a similar vein, constituents fear increased federal oversight and land use restrictions, especially on private property. Third, there is a general lack of understanding about how the WSRA functions. As one conservation advocate explained, “The adjectives Wild and Scenic Outstandingly Remarkable Values just don’t get politicians on your side.” To contend with the “nature as resource” versus “conservation of nature” paradigm, Henstra (2015) suggests reframing current conservation policies to reflect the “urgency” expressed in calls to advance conservation policy, such as Strayer and Dudgeon’s 2010 call. Such is the case because perceptions of threat can influence public support for policy making and implementation (Stern 2000). Moreover, adaptation concepts rooted in current political demands seemingly pique interest from decision makers, thus foster- ing acceptability of policy adoption (Schmidt-Thome et al. 2013). Hence, advancing WSRA application for river conservation will require framing those adjectives in terms germane to stakeholder concerns.

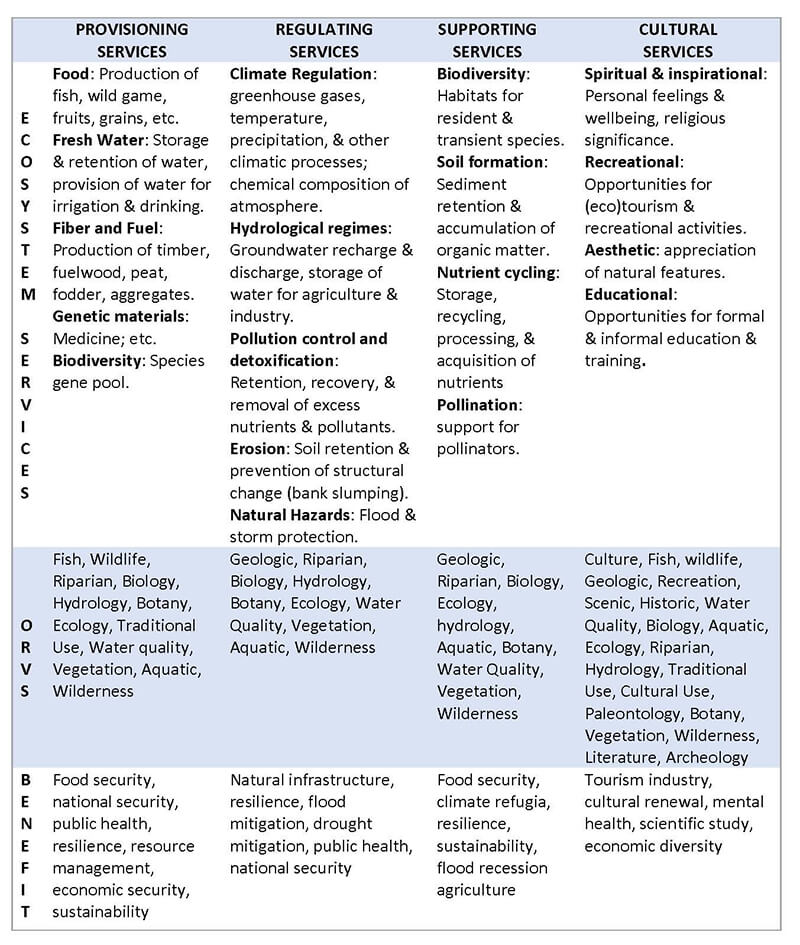

An ecosystem service framing is supported as a method to situate biodiversity within an influential political-economic construct by placing value on the services rivers provide to society, including clean water, flood reduction, groundwater recharge, fisheries, and recreation (Vörösmarty et al. 2010; Tickner and Acreman 2013; Palmer et al. 2008). This framing, in turn, provides policy makers a tool to evaluate the trade-offs between development and conservation (Liu et al. 2010). Thus, ecological economists praise ecosystem services as an effective mechanism for advancing conservation policy (Daily 1997; Liu et al. 2010), as “a means to an end” (Dempsey 2016, p. 5). Ecologists use ecosystem services to rally for increased biodiversity protection and resilience in the face of climate change (Di Baldassarre et al. 2014; Fleishman et al. 2011; Seppälä, Buck, and Katila 2009). Quoting Jessica Dempsey, ecosystem services can be “better understood as a political-scientific strategy to create new interests in nature, to prevent ‘stupid decisions’” than as a means of creating new market commodities (2016, p. 10).

Although the term ecosystem services did not exist during the environmental policy era of the 1960s when the WSRA was being negotiated, the designation of a stretch of river arguably centered on the protection of ecosystem services. For example, facing losses from dam developments in the Columbia Basin, the Pacific Marine Fisheries Commission sought protection for anadromous fish spawning habitat in Idaho’s Salmon River as evidenced from archival documents (James 1966). Over time as ecological science and education progressed, river resources fitting the characteristics of ecosystem services were included in “Other” ORV designations as shown in Figure 5. One agent reported:

It was very uncommon to see “ecology” or “ecological” used in ORV analysis, but I’m starting to see that more and more often and typically in BLM what that means is that we’ve got a kind of intact eco- system that provides all the services. It’s got a full range of flows, it’s got a nice riparian area, it’s got a bird population, it’s got the fish there that should be there, and you know we’re putting it forth like “wow, this is an outstanding example of a river that is functioning ecologically like it should” and I’ve noticed how people react to that and that’s a very strong selling tool … we say hey “one of the things is that this [river] is a completely high to low full range of elevation, full range of species, full range of ecological functions, it still works and that alone is a reason to protect it” and people say “oh” … they think of it as a whole system, they don’t think of it as it’s great recreation or it’s great fishing.

Against that backdrop, Tickner and Acreman’s (2013) typology has been adapted to situate ORVs within the four widely used categories of ecosystem services to demonstrate the benefits they provide and to examine the utility of using the WSRA as an ecosystem-based adaptation policy. Figure 6 illustrates that ORVs often span multiple categories providing a host of benefits to society such as food security, public and mental health, a tourism industry, natural infrastructure for flood and drought mitigation, resilience, scientific study, and cultural renewal, among others.

Adapting a Visionary Policy for a Resilient Future

As we look toward a future characterized by a changing climate and greater demands on water resources, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act provides an opportunity for a more ecosystem-based adaptation policy framework. Federal land management agencies play a vital role in identifying and protecting river resources important to society through their resource management plans. Yet, despite an ostensibly broadly applicable framework for protecting rivers, the variegated patchwork of land management agencies and a lack of political support troubles both the identification and designation of any broadly applicable, holistic river conservation system. Thus, reframing the WSRA and its outstandingly remarkable values as a policy designed to protect ecosystem services may help advance three matters ripe for improvement within the national system: resource protection, training, and relevancy (TNC 2016).

First, utilizing consistent framings for ecoregion identification while taking into consideration the distribution of rivers across those ecoregions provides an opportunity to better protect a complete portfolio of ecosystem services (e.g., biodiversity, erosion control, fisheries, flood mitigation). The Nationwide Rivers Inventory provides a starting point for closing the gap in underrepresented ecoregions (depicted in Figure 7). As climate change makes river conservation urgent, this approach to fulfilling the WSRA’s conservation intent could expand resource protection while mitigating impacts of climate change on river resources. Given the flexible design of the WSRA and afforded agency discretion, standardizing ecoregion models could be accomplished through a directive from the Interagency Wild and Scenic Rivers Coordinating Council.

Second, if conservation advocates and agency personnel adopt a consistent framework for ecoregion identification, such as the EPA’s Level III Ecoregions, this method could serve to streamline training as well as eligibility and suitability studies for designations, ultimately reducing human and financial resources. Agencies may be reluctant to replace their proprietary system, but moving toward standardization may facilitate interagency coordination for administering the national system.

Finally, framing ORVs as ecosystem services situates the descriptive language of the policy’s “Wild and Scenic” and “Outstandingly Remark- able Values” within a widely accepted political-economic framing and offers stakeholders a model for weighing the trade-offs between conservation and development – essentially making ORVs relevant to decision makers. After all, if you can frame the protection of an intact riparian forest or floodplain in terms of reducing the risk of impacts brought by more frequent and intense floods (or droughts) in the face of climate change – essentially an insurance policy for which the federal government pays the premium – then landowners and politicians might turn an otherwise deaf ear toward negotiations over conservation policy. Moreover, as the WSRA was negotiated during an era of increased understanding of the environment through ecological science, we must adapt the policy to incorporate new scientific under- standings of climate impacts on river resources. Suggesting this trend may be under way, “climate refugia,” an ecosystem service for fisheries resilience, recently factored into ORV assessments of proposed designations in Montana’s cold headwaters streams.

DENIELLE PERRY is an assistant professor at Northern Arizona University in the School of Earth Sciences and Environ- mental Sustainability (SESES). She has nearly two decades of experience guiding on, advocating for, and researching rivers in the United States and Latin America; email: dperry3@uoregon.edu.

References

Abell, R., M. L. Thieme, C. Revenga, M. Bryer, M. Kottelat, N. Bogutskaya, …P. Petry. 2008. Freshwater ecoregions of the world: A new map of biogeographic units for freshwater biodiversity conservation. BioScience 58(5): 403–414.

Daily, G. C., ed. 1997. Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Dempsey, J. 2016. Enterprising Nature: Economics, Markets, and Finance in Global Biodiversity Politics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley- Blackwell.

Di Baldassarre, G., J. S. Kemerink, M. Kooy, and L. Brandimarte. 2014. Floods and societies: The spatial distribution of water-related disaster risk and its dynamics. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, ] 1(2): 133–139.

Diedrich, J., and C. Thomas. 1999. The Wild & Scenic River Study Process. Retrieved from https://www.rivers.gov/documents/study- process.pdf.

Fleishman, E., D. E. Blockstein, J. A. Hall, M.B. Mascia, M. A. Rudd, J. M. Scott.…A. Vedder. 2011. Top 40 priorities for science to inform US conservation and management policy. BioScience, 61(4): 290–300.

Glaser, B. G., and A. L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Henstra, D. 2015. The tools of climate adaptation policy: Analysing instruments and instrument selection. Climate Policy 16(4):1–26.

James, M. C., ed. 1966. 18th Annual Report of The Pacific Marine Fisheries Commission for the Year 1965. Report. White House Central Files, Subject File FG 711 Pacific Marine Fisheries Commission. Austin, TX: LBJ Presidential Library.

Liu, S., R. Costanza, S. Farber, and A. Troy. 2010. Valuing ecosystem services: Theory, practice, and the need for a transdisciplinary synthesis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1185: 54–78.

Munang, R., I. Thiaw, K. Alverson, M. Mumba, J. Liu, and M. Rivington. 2013. Climate change and Ecosystem-based adaptation: A new pragmatic approach to buffering climate change impacts. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 5(1): 67–71.

Murphy, A. B. 2013. Advancing geographical understanding: Why engaging grand regional narratives matters. Dialogues in Human Geography 3(2): 131–149.

NOAA. 2017. Rivers – Habitat of the month. Retrieved from http://www.habitat.noaa. gov/abouthabitat/river.html, accessed May 22, 2017.

Omernik, J. M., and G. E. Griffith. 2014. Ecoregions of the coterminous United States: Evolution of a hierarchical spatial framework. Environmental Management 54(6): 1249–1266.

Palmer, M. A., C. A. Reidy Liermann, C. Nilsoon,Flörke, J. Alcamo, P. S. Lake, and Bond. 2008. Climate change and the world’s river basins: Anticipating management options. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 6(2): 81–89.

Parenti, C. 2015. The 2013 ANTIPODE AAGLecture, The environment making state: Territory, nature, and value. Antipode 47(4): 829–848.

Schmidt-Thome, P., J. Klein, A. Nockert, L. Donges, and I. Haller. 2013. Communicating climate change adaptation: From strategy development to implementation. In P. Schmidt-Thome. Climate Change Adaptation in Practice. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell1–9.

Seppälä R., A. Buck, and P. Katila. 2009. Adaptation of Forests and People to Climate Change: A Global Assessment Report. IUFRO World Series, Vol. 22. Retrieved from http://www.iufro.org/ science/gfep/adaptaion-panel/the-report/. Stern, P. C. 2000. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environ- mentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues 56(3): 407–424.

Strayer, D. L., and D. Dudgeon. 2010. Freshwater biodiversity conservation: Recent progress and future challenges. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 29(1): 344–358.

Thompson, I. D. 2015. An overview of the science–policy interface among climate change, biodiversity, and terrestrial land use for production landscapes. Journal of Forest Research, 20(5): 423–429.

Tickner, D., and M. Acreman. 2013. Water security for ecosystems, ecosystems for water security. In Water Security Principles, Perspectives and Practices, ed. B. L. M. Zeitoun (pp. 130–147). New York: Routledge.

TNC. 2016. November 28. W.S. Wild & Scenic Rivers Act webinar. Retrieved from https:// tnc.app.box.com/s/mzv7kw8ax33javztln-4lm08t57f8aqom, accessed May 4, 2017. USFS. 2015. FSH 1909.12 – Land Management Planning Handbook, chapter 80 – Wild and scenic rivers.

Vörösmarty, C. J., P. B. McIntyre, M. O. Gessner, D. Dudgeon, A. Prusevich, P. Green, P. M. Davies. 2010. Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity. Nature 467(7315): 555–561.

Walker, P. A. 2003. Reconsidering “regional” political ecologies: Toward a political ecology of the rural American West. Progress in Human Geography 27(1): 7–24.

WSR. N.d. About the WSR Act. Retrieved from https://www.rivers.gov/wsr-act.php, accessed April 13, 2017.