Influences on Wilderness Visitor Behavior

Science & Research

April 2016 | Volume 22, Number 1

by STEVEN R. MARTIN and JESSICA L. BLACKWELL

PEER REVIEWED

Abstract: As Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs) become more common, more people may bring them into the wilderness, potentially influencing visitors’ decision making and behavior due to a perceived increase in safety. By way of a wilderness visitor survey in Sequoia-Kings Canyon Wilderness (n = 635) and follow-up personal phone interviews (n = 65), we examined how PLBs may influence wilderness visitors. Our results suggest a possible increase in both solo travel and cross-country (trailless) travel in wilderness by PLB users. This has the potential to increase search and rescue (SAR) events, and lead to increased resource and social impacts in trailless areas that are currently pristine or near pristine. Understanding how handheld information and communication technology influences the behaviors and decision making of wilderness visitors is important for managing wilderness SAR operations, managing wilderness resource conditions, developing visitor management guidelines, and educating visitors in appropriate use of technology in the wilderness.

Introduction

Our society is experiencing a technological revolution in the use of handheld information and communication technology. The recent advances in wireless technology have made information and communication devices more portable, more affordable, and more ubiquitous than ever before. Devices such as cell phones, satellite phones, Personal Locator Beacons, GPS units, and smartphones have created unprecedented access to information and communication systems. These devices have been integrated into our lives and have influenced on a daily basis the types of experiences we now have. They have also had a significant influence on how we interact with each other and our environment. Wireless systems let people use these technologies in places they could not have previously, including the wilderness. “Mobile technologies are becoming commonplace in the wilderness, and their presence is altering our relationship to natural environments, our experience of being in the wilderness, and, in some cases, the wilderness landscape itself” (Wiley 2005, p. 5). Our article addresses two important questions we should ask about the use of these emerging technologies in wilderness: How might the use of such technology influence visitor behavior (Martin and Pope 2012), and how might wilderness experiences be affected (Freimund and Borrie 1997)?

The spread of satellite-driven mobile technologies into remote areas of wilderness is significant because, for many people, wilderness is described or defined as an area absent of human technological influence (Dawson and Hendee 2009; Roggenbuck 2004; Wuerthner 1985). Wiley (2005, p. 6) identified several areas of “tension and conflict” related to technology and wilderness, including “risk versus security, solitude versus connectivity, [and] mediation versus direct experience.” Mobile technologies such as satellite phones and Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs) may provide security, but they may also alter the perception of risk, warping one’s view of the wilderness and potentially leading to increased search and rescue incidents. Mobile communication devices can provide connectivity to others outside the wilderness, drastically altering the solitude element of a wilderness experience. Information and communication technology can alter one’s direct wilderness experience by acting as a mediating force; in other words, rather than experiencing and interacting with the wilderness directly, one may interact with and experience the wilderness partly through a digital interface – the technology mediates the experience.

The tensions of risk versus security and solitude versus connectivity may be the most prevalent concerns for how information and communication technology may influence the wilderness experience, specifically with regard to visitor decision-making and risk-taking behavior. This is because communication technology can influence perceptions of safety in the wilderness. Communication technologies in particular have the ability to make people feel more connected, even when they are in solitude, and more secure, even in an unfamiliar or risky environment, becoming “less dependent on their own ability and awareness as they become more dependent on technology” (Borrie 2000, p. 1).

Information and communication technology is one of the most notice-able social factors negatively impacting the wilderness experience in the opinion of California wilderness managers, who felt that technological devices may decrease “self-sufficiency, risk, solitude, and remoteness, many of the characteristics that – to them – define wilderness” (Steiner 2012, p. 9).

Technology thought to reduce the risks associated with wilderness recreation may have significant con-sequences for the visitor’s ability to make appropriate decisions. There is “potential for underprepared and/or overly confident users to substitute technology for common sense, experience and skill, and to make decisions based on unrealistic perceptions of both risk and the ease and avail-ability of rescue” (Martin and Pope 2012, p. 120).

In a 2009 study, overnight visitors to the King Range Wilderness in California were asked a series of questions about their perceptions of technology’s influence on safety in the wilderness. Most respondents reported that they would not be likely to take chances that could increase risks because they had technology with them. But there was a group of “pro-technology” visitors who felt that technology increased their safety in the wilderness, identified themselves as significantly greater risk takers who would be more likely to take chances that increased risk if they had technology with them, and would be more likely to use technology to request rescue (Pope and Martin 2011).

Methods

Wilderness visitor survey data were collected in summer and fall of 2011 for Sequoia–Kings Canyon (SEKI) National Parks (Watson et al. 2015). The sample population consisted of adult overnight recreation visitors to the SEKI Wilderness from May 22, 2011 through September 30, 2011. Surveys (with prepaid return envelopes), reminder postcards, and replacement surveys were mailed to a systematic sample of 1,043 visitors who were issued wilderness permits. Respondents could return the survey by mail, or complete the survey online (SurveyMonkey). The survey included questions regarding visitor use of, and beliefs about, handheld information and communication technology, and its possible effects on decision making.

In addition to the written survey, respondents were asked if they would be willing to participate in follow-up interviews regarding the use of technology in wilderness, and if so, to provide an email address where they could be reached to schedule an interview. Respondents who indicated their willingness to participate in a follow-up interview (n = 391) were categorized into two strata: those who had carried a Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) on their trip (Figure 1), and those who had not. Interview participants were then randomly chosen from each of the two strata. A total of 65 people were interviewed, 33 of whom carried a PLB, and 32 who did not. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and responses coded into relevant thematic categories by the interviewer.

Results

Survey Sample

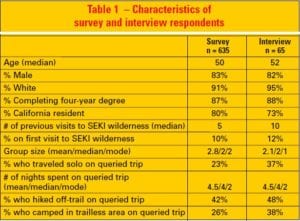

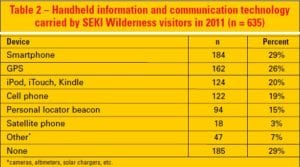

We received 635 completed and valid surveys, for a response rate of 61%. Key characteristics of the survey respondents are summarized in Table 1. Additionally, 76% had visited six or more other wilderness areas in their lifetime, and 35% had visited a wilderness area more than five times in the past year. Of those who camped in a trailless area, the mean number of nights camped there was 2.6. Smartphones were the most commonly carried type of handheld communication and information technology (29%), followed by GPS (26%); 15% carried a PLB (Table 2).

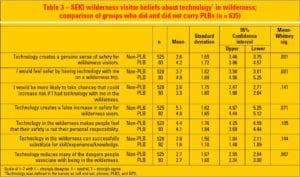

Table 3 compares responses of PLB users and nonusers to statements relating to technology in wilderness (defined in the survey as cell and satellite phones, PLBs, and GPS). PLB users were more likely to agree that technology creates a genuine sense of safety in wilderness and felt safer having technology with them, than did non-PLB visitors. Both groups disagreed that they would be more likely to take risks because they had technology with them, that technology reduces wilderness dangers, and that technology can substitute for skills, experience, or knowledge. The statements that respondents were most likely to agree with were that “technology creates a false increase in safety for wilderness users” (non-PLB users mean = 5.1, PLB users mean = 4.8, on a 7-point scale); and PLB users agreeing that they would feel safer by having technology with them on a wilderness trip (mean = 4.9).

Interview Sample

Table 1 summarizes characteristics of the interview participants, who were similar to the survey respondents except that they had visited the SEKI Wilderness more often, were somewhat more likely to have traveled solo, and were somewhat more likely to have camped overnight in a trailless area.

Among those who traveled with a PLB (n = 33), reasons for doing so were categorized as follows: 20 gave reasons pertaining to safety, “insurance,” backup, or in case of emergency; 15 gave reasons related to communication with family and/or to provide peace of mind to family members by alleviating loved ones’ concerns while on a wilderness trip. Six people said it was a way to justify solo travel, alleviating concerns for both the individual traveling alone in the wilderness and for the family members back home; and two people gave reasons related to group travel, with one stating that it is a nice tool for the wilderness community, not just for those in one’s own group, but for anyone in another group who could benefit from having someone with a PLB come across their path during a worst-case situation.

Of the 33 interview participants who traveled with a PLB, 30 said that having one with them did not influence any decisions they made while on the trip, two said “it might,” and one said that it did. The one visitor who said that it did stated that he climbs class three peaks solo with two replacement knees, and that having a PLB was a part of making the decision to travel in those conditions. One of the “it might” respondents said that having a PLB “allows me to keep doing the same things I did before; perhaps I would be less inclined to continue the same behavior, be more cautious” otherwise.

Eight of the 32 interview participants who did not carry a PLB said that traveling with a PLB could or might influence their decisions. Examples included deciding to travel in trailless areas, and that it would make other areas more available (i.e., they might visit places with a PLB that they otherwise would not visit).

Of the 33 interviewees who traveled with a PLB, 28 said that having a PLB with them did not influence what they did or where they went, while 5 said that it did. Examples included “Knowing I have it, I continue to hike alone in trailless areas,” and “I do solo backpacking, am more comfortable [with a PLB.]” Of the 32 interviewees who did not travel with a PLB, 10 said that traveling with one could have an influence on what they did or where they went, if they had one. Examples included going farther out of one’s comfort zone and letting the PLB substitute for instincts, being more likely to travel into trailless areas, taking more hazardous routes, spending more time in trailless areas, exploring areas they otherwise would not explore, and being more likely to travel alone.

Three of the 33 interview participants who carried a PLB said that having one influenced their decisions to travel in environmental or terrain conditions they otherwise would not have, including taking more risk and traveling in steep terrain. Of the 32 interviewees who did not travel with a PLB, 11 said that having a PLB would influence their decisions to go to more remote areas, to go farther alone, and to travel in unknown or more mountainous or dangerous terrain.

None of the 33 interviewees who carried a PLB said they did any-thing on their trip that might have increased their risk because they had a PLB with them. Seven of the 32 who did not carry a PLB said that carrying one could influence them to take more risk, including traveling in trailless areas, attempting more rugged terrain, canyoneering, crossing snowpack and steep snowfields, and solo travel.

When asked directly if they would be more likely to travel alone because they had a PLB, 18 of the 33 PLB subjects said they would be more likely to travel alone because they had a PLB. Ten of the 32 non-PLB subjects said that if they did have one, they would be more likely to travel alone in the wilderness.

Interviewees were asked if hav-ing a PLB affected how they engaged with the wilderness. Of the 33 interviewees who carried a PLB, 4 answered yes in a positive way, saying they were able to enjoy it more, they were not as worried, they didn’t feel guilty making their family worry, and that it cut down on the uneasiness. Two answered yes, but in a negative way: “When I have to wait for it, it slows me down,” and “I wish I could leave it behind because there is a connectedness; I prefer complete solitude but carry one for family and for safety.”

Of the 32 interview participants who did not carry a PLB, 10 said they thought having a PLB would have a positive effect on their wilderness experience, allowing them to have peace of mind, and enabling them to go into the wilderness alone and/or to go into trailless areas or more remote areas. One said that PLBs would enable people to access less-visited portions of the wilderness and areas with more options for places to go and things to do, therefore improv-ing their wilderness experience. One person said that having a PLB would enable them to stay in touch with their babysitter so both adults could go on the wilderness trip together. Six people said that carrying a PLB would negatively affect their wilder-ness experience – the PLB would take away from the value of being isolated, could influence people to do stupid stuff, increase accidents, detract from the self-reliance of the experience, detract due to the thought that someone could track you, and it could “blur a necessary sense of taking responsibility for my actions.”

Discussion

From the written survey, we found that 15% of SEKI Wilderness visitor groups carried a PLB in the summer of 2011. As these devices become more commonly known, lighter, easier to use, and cheaper, one can only speculate on how many groups will carry them in the future, but it is almost certainly likely to increase. Monitoring this would be relatively easy for areas that require permits, and it would provide managers with an opportunity to educate visitors about the appropriate use of PLBs.

We examined visitor beliefs about handheld information and communication technology in wilderness using a set of statements adapted from Pope and Martin (2011). The general pattern of responses was similar to Pope and Martin, although we did not find as many significant differences between PLB-users and non-PLB users in our study. This shouldn’t be surprising, since carrying a PLB doesn’t necessarily make one “pro-technology,” nor does not carrying one necessarily make one “anti-technology.” The statement garnering by far the least amount of agreement from both groups was that technology could successfully substitute for skill, experience, and knowledge in the wilderness, a finding that mirrors that of Pope and Martin (2011). The statements receiving the most agreement from each of the groups (PLB and non-PLB) were the same, or very similar, to what Pope and Martin found, but were near-opposite statements from each other. Non-PLB users felt strongest that technology creates a false increase in safety for wilderness users, while PLB users felt strongest that they would feel safer by having technology with them on a wilderness trip. Visitors who carry PLBs and those who don’t, at least in our study, have very different opinions about the safety advantage of carrying one.

Turning to the interview results, we found that most PLB users travel with them for safety reasons, to stay in communication with family, and because it was a way to facilitate, and in some cases even justify, solo travel. Nearly all PLB users we interviewed said that having the device did not influence their decision making, and none of them said that they did any-thing that might have increased their risk because they had a PLB with them. However, when more specific follow-up questions were asked, more of the PLB users (between 9% and 54%, depending on the question) admitted that carrying a PLB did influence at least one of the fol-lowing: where they went, what they did, whether they traveled in certain environmental or terrain conditions, and whether they traveled alone. Carrying a PLB does appear to influence some decisions, whether or not the person carrying it thinks of it in those terms. According to our interviewees’ self-reports, having a PLB did not influence their real-time, on-the-ground, risk-taking behaviors during the trip. (It would be interesting, although perhaps challenging, to collect actual behavioral data on this question.) Carrying a PLB does, however, appear to influence pretrip decisions such as whether to travel solo, travel cross-country in trailless areas, or tackle more difficult terrain or more remote locations, at least for some visitors.

Wilderness managers and scientists (Cole 1997; Cole 2001; Oye 2001) have expressed concern about the potential for increased resource and social impacts in low-use, often trailless portions of wilderness areas, arguing that such areas are “typically the most pristine portions of our wilderness resource and by their very nature the most sensitive to changes in visitor use levels or patterns” (Van Horn 2007). Visitor experiences in these remote areas may also change; Van Horn notes that “once a user-formed trail exists in a cross-country area, the experience in the future changes from exploration and discovery to one of simply following the obvious signs left by those that have been there in the past.”

Most PLB users said that having the device with them did not alter how they engaged the wilderness, and some interviewees said that it improved their experience – that having a PLB allowed them to enjoy the wilderness more because it cut down on uneasiness, worry, and the guilt of making family members worry. Other interviewees expressed concerns about PLB use in wilderness, such as visitors needing to be able to self-rescue, and knowing when to use or not use a PLB. Several interviewees suggested establishing a protocol for acceptable PLB use in the wilderness, similar to Leave No Trace (LNT) guidelines, so people do not use PLBs inappropriately or irresponsibly. One person had rescue personnel in mind:

Changes in wilderness traveler behavior engendered by beacons are an issue. Such changes in behavior have important consequences for rescue personnel who might be called upon to help people in need. I think some serious education is necessary for beacon owners and potential owners as to just what calling [for] a rescue means and the consequences.

Understanding how handheld information and communication technology influences the behaviors and decision making of wilderness visitors is important for managing wilderness search and rescue operations, managing wilderness resource conditions, developing visitor management guidelines, and educating visitors in appropriate use of technology in the wilderness (e.g., whether to post detailed cross-country route information online, guidelines on when to use a PLB to request a rescue). To the extent that PLB use provides an impetus or a rationale for more visitors to travel alone and/or in trailless areas, and we did find some evidence for this, wilderness managers should probably be concerned about the potential increase in search and rescue calls, as well as the potential for resource and social impacts spreading into previously pristine or near-pristine areas.

Although PLBs may not influence a large percentage of wilderness visitors to travel alone or in more remote, trailless areas, even a relatively small percentage of visitors doing so could have significant implications for the condition, management, and monitoring frequency of these areas. On the plus side, PLBs may provide both visitors and the people they leave behind with peace of mind benefits derived from enhanced safety and security (real or perceived), resulting in wilderness visits that otherwise might not happen.

Next steps for managers, researchers, and SAR personnel could include development of LNT-type guidelines for appropriate use of PLBs, and an accompanying visitor education effort; creation of a national wilderness database to monitor SAR events, noting variables such as what technology (if any) the person/group had and used, group size, distance from a trailhead, whether they were in a trailless area, and some type of assessment of the emergency level of the situation (i.e., how justified was the SAR request); and monitoring how many wilderness visitors are using PLBs, either as part of an existing larger visitor monitoring effort, and/or as a common component of future wilderness visitor studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alan Watson (ALWRI) and Gregg Fauth (SEKI) for their support and collaboration, and to thank our anonymous reviewers for their helpful and insightful comments on the draft manuscript.

STEVEN R. MARTIN is professor and chair of the Department of Environmental Science and Management, Humboldt State University; email: Steven.Martin@ humboldt.edu.

JESSICA L. BLACKWELL is a natural resource specialist for the USDA Forest Service, working as a special uses permit administrator for the Shasta Lake District of the Shasta-Trinity National Forest, located in Mountain Gate, CA.

View more content from this issue >

References

Borrie, W. 2000. The impacts of technology on the meaning of wilderness. In Personal, Societal, and Ecological Values of Wilderness: Sixth World Wilderness Congress Proceedings on Research, Management, and Allocation, Volume II, October 24–29, 1998, Bangalore, India, comp. A. Watson, G. Aplet, and J. Hendee (pp. 87-88). Proc. RMRS-P-14. Ogden, UT: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Cole, D. 1997. Recreation management priorities are misplaced – allocate more resources to low-use wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 3(4): 4–8.

———. 2001. Balancing freedom and protection in wilderness recreation use. International Journal of Wilderness 7(1): 12–13.

Dawson, C., and J. Hendee. 2009. Wilderness Management: Stewardship and Protection of Wilderness Values, 4th ed. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Freimund, W., and B. Borrie. 1997. Wilderness @ Internet: Wilderness in the 21st century are there technical solutions to our technical problems? International Journal of Wilderness 3(4): 21–23.

Martin, S., and K. Pope. 2012. The impact of hand-held information and communication technology on visitor perceptions of risk and risk-related behavior. In Wilderness Visitor Experiences: Progress in Research and Management, April 4–7, 2011, Missoula, MT, comp. D. N. Cole (pp. 119-126). Proc. RMRS-P-66. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Oye, G. 2001. A new wilderness recreation strategy for national forest wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 7(1): 13–15.

Pope, K., and S. Martin. 2011. Visitor perceptions of technology, risk, and rescue in wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 17(2): 19–26, 48.

Roggenbuck, J. 2004. Managing for primitive recreation in wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 10(3): 21–24.

Steiner, A., D. Williams, and G. Fauth. 2012. Fifty Years of Wilderness Management: The Experiential Knowledge of Long-Term Wilderness Users of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Report submitted to Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute and Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, December 2012.

Van Horn, J. 2007. GPS and the Internet. International Journal of Wilderness 13(3): 7–11.

Watson, A., S. Martin, N. Christensen, G. Fauth, and D. Williams. 2015. The relationship between perceptions of wilderness character and attitudes toward management interventions to adapt biophysical resources to a changing climate and nature restoration at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Environmental Management 56(3): 653–663.

Wiley, S. 2005. Repositioning the wilderness: Mobile communication technologies and the transformation of wild space. Paper presented at the Conference on Communication and the Environment, June 24–27, 2005, Jekyll Island, GA.

Wuerthner, G. 1985. Managing the wild back into wilderness. Western Wildlands 11(3): 20–24.