Fall on the Wolf River on the Menominee Reservation. Photo credit: Brian Grignon.

Medicine Fish Is Leading the Way to Heal, Build, and Inspire Menominee Youth through the Wild and Scenic Wolf River: An interview with Bryant Waupoose Jr., Founder of Medicine Fish

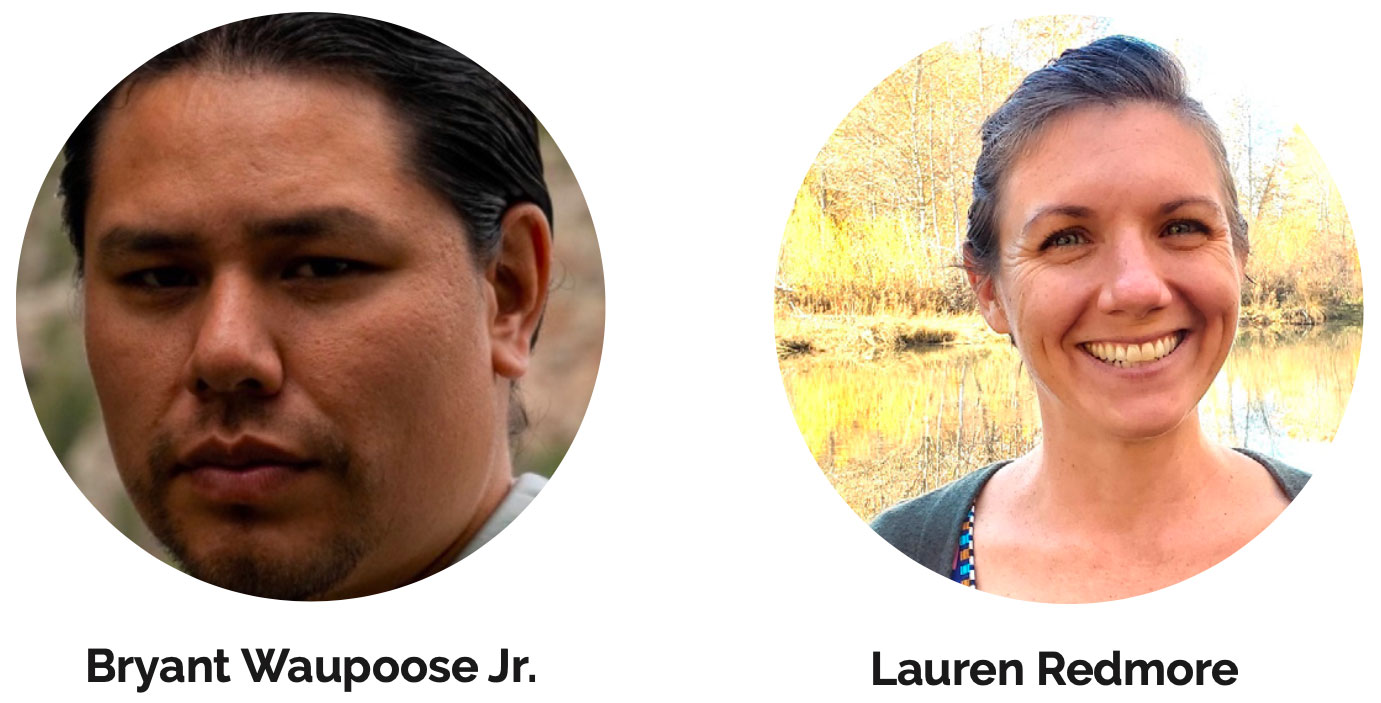

by BRYANT WAUPOOSE JR. and LAUREN REDMORE

Soul Of The Wilderness

December 2023 | Volume 29, Number 2

From a bird’s eye view, the Menominee Reservation is a forested oasis in sharp relief from neighboring landscapes of dairy farms spanning northeastern Wisconsin. The Menominee people have cared for the land and waters for over 10,000 years, and the land and waters have given life back to the people (Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin 2004). Garden beds where early Menominee people planted traditional first foods and elder plants – plants that sustained the Menominee culturally, spiritually, and physically – as the last glaciers retreated are still visible across their lands today and represent a modern marvel of integrated farming (Morales 2017). Today, the Tribe operates a successful timber company, and their management practices are widely recognized for increasing the quality of their forest (Buckley 2023). But the land represents much more than economic and environmental opportunity – it is the embodiment of self-determination for the Tribe and one that Tribal members do not take for granted.

The Menominee originally inhabited around 10 million acres of land across the Midwest (Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin (MITW) 2004). The Menominee had contact with early European settlers dating back to the 1600s but began to be significantly impacted by them starting in the early 1800s when the US government began to take seriously the project of westward expansion. In the 1820s, New York State Tribes, in particular the Oneida, Stockbridge, and Munsee Indians, were pushed from their territory, and sought to settle on Menominee land (MITW 2004). Chief Oshkosh, the leader of the Menominee at the time, agreed, recognizing their plight, and carved out a portion of his people’s remaining land in goodwill (MITW). Over the following decades through 1848, the Menominee signed seven treaties with the US government when Wisconsin was organizing for statehood, ceding significant portions of their land to settlers (MITW 2004). The US Government sought to extinguish all Native American land claims in the new state of Wisconsin and told Chief Oshkosh and his cabinet that they would be given pristine land in Minnesota (MITW 2004). However, upon arriving on a scouting visit to this new land in 1850, Chief Oshkosh found that the land both offered little in terms of favorable hunting opportunities and was contested by Ojibwe and Sioux Tribes. In response, he traveled to Washington, D.C., to request that the Tribe remain in Wisconsin. In 1854, the US government and Menominee Tribe signed the Wolf River Treaty, solidifying their claims to 250,000 acres of their homelands which is now the present-day reservation (MITW 2004).

This initial contact began a long and com- plicated relationship between the Menominee Tribe and the US government. “Since their first treaty with the United States in 1827, the Menominee and their more-than-human kin experienced catastrophic changes that threatened many of their ancestral practices” (Hitch and Grignon 2023, p. 253). This includes a wide range of sociocultural impacts, specifically the loss of their ability to move across the land- scape seasonally, as well as the subsequent creation of the Menominee Indian boarding school at Keshena Falls to replace Menominee agriculture, religion, and language with Western counterparts (MITW 2004). The loss of lifeways, language, and religion intersected to cleave Menominee relationships with the land and all of creation that had sustained them for millennia (Kline, Bruch, and Binkowski 2009).

Yet even the Tribe’s ability to manage their own land was up for grabs as the USDA Forest Service clear-cut significant portions of the reservation starting in the 1920s, leading to a successful lawsuit in the 1950s for environ- mental damages (Menominee Tribe of Indians 1950). In the 1960s, as the US waged assimila- tion policies, the Tribe’s federal recognition was terminated, and they lost their right to self-governance, important federal funding sources, and other significant tribal treaty rights (MITW 2004). In 1973, the Tribe regained federal recognition through a congressional act and reestablished the reservation in 1975 (MITW 2004). But in the years leading up to this, the signing of the Wild and Scenic River Act established a 24-mile segment of the Wolf River entirely within the current-day boundaries of the reservation as one of the original Wild and Scenic Rivers. Suddenly, when the Tribe regained recognition, they found themselves managers of one of the nation’s most protected rivers that, until the installation of downstream dams in the early 1900s, had been critical spawning grounds for nama’o, the long-lived lake sturgeon that sustained human and more-than-human life at Keshena Falls (Kline, Bruch, and Binkowski 2009).

The impacts of this tumultuous experience are far ranging: Menominee members have lower life expectancy, higher rates of alcohol and drug abuse, lower median household incomes, and higher rates of poverty, among other social determinants, than neighboring white communities (MITW 2004). Yet through all of these challenges, the Menominee people remain resilient, striving for self- determination. Today, one group is working to reinvigorate the Menominee connection to place. Medicine Fish is a newly established nonprofit organization working to connect Menominee Tribal youth with Menominee culture and place, including nama’o and the Wild and Scenic Wolf River. Bryant Waupoose Jr. and his colleagues bring a holistic approach to healing the intergenerational trauma of kinship destruction, land dispossession, and cultural erasure through fly fishing. While many think of fly fishing as recreation, Bryant and his team understand it is an act of creation—the connection of people and place, across time and through generations. Bryant and I spoke just after Father’s Day when he took some youth in the Medicine Fish program to learn how to fish at night along the Wolf River. In this interview for the International Journal of Wilderness, he shares a little bit about where he came from and how he and his team came to develop the Medicine Fish approach to heal, build, and inspire youth on the Menominee Reservation.

Bryant, tell me about yourself and how Medicine Fish came to be.

Growing up inside of an Indigenous community impacted by colonization is full of many chal- lenges, like poverty, substance abuse, alcoholism, physical and sexual abuse. European contact resulted in the loss of cultural practices and access to our first foods and medicines, which increased the rate of diseases across our communities. I grew up on the Menominee Reservation in poverty and was raised by my grandparents until my teenage years when they both were diagnosed with diabetes and their health deteriorated. As I transitioned into later teenage years and early adulthood, I started selling illegal drugs, doing drugs, and drinking alcohol—decisions that didn’t help me in my life. I was able to stay alive and not be incarcerated. I had my first born son and shortly after met my wife, Deeann, and together we realized we needed to break this generational cycle. At 23 years old we were married, we started our family, and we chose to walk in this different direction. We traveled to different Indigenous communities and had many lessons of humility in reestablishing ourselves and rebuilding our life around us. But we kept that core and sense of prayer unity and resilience to break the generational cycle of trauma. We moved around these different communities, into the plains—North Dakota, South Dakota area—and were inspired by the positive Indigenous activism we saw. Then I found this calling to bring that home.

When we came home at the end of 2019, we knew we wanted to help our community, but we weren’t sure how. COVID hit and neither one of us had jobs, and we brought a new baby into this world. We went through another lesson of humility trying to build again around ourselves and our family. This time we chose to do it by giving our time and effort to the young people of our community. So I took this passion of mine—which I found also is one of my keys to my own success in my wellness and connection to creation—fly fishing. Through prayer and my spiritual foundation—being out on the water and the desire to know something about the rhythm and the birds and the sound of solitude and being alone—it had tremendous effect on my emotional and spiritual well-being. I got back into our forest and tried to do my time out there, learning what I could by navigating the river systems inside of the reservation boundaries and trying to under- stand more places. I became very close friends with a brother of mine, Brian Grignon, and we talked about these skills that we developed outside, being underwater catching fish, how much it helps us and how much it could help the young people of our community. In 2021, we took a few kids camping, and today it is safe to say that we changed their lives forever through what we have done.

How does the idea of home enter into your work?

The sense of home for me is many things. That relationship I was able to build over time with the land and the water really called my spirit—from where I played in the sand to where I would swim to the smell of the scent of the air, the trees, the sounds of the birds in our area. There’s so many things that I didn’t notice until I left home. When my wife and I moved our four children, I realized that this song, this place, it was helping me in so many different ways, and it was actu- ally calling my spirit back. For us to be at home today, we get to walk along on some of these trails and trees that go back so far in time with our relatives and our people. We have trees that are 200, 300 years old. To think about the things that they’ve seen and how long they’ve actually been here, and to think of my lineage! Of my grandparents and grandmothers, and how long they’ve been here and how far back our paths go. I have a deep relationship and I’m still learning about how connected we actually are to this area, to this forest, to these waters—that is what’s really special about existing on ancestral land. Our team carries this connection to place and kin throughout our work with our community.

Fly fishing is not a traditional practice for the Menominee people, but this activity is central to the inspiration behind Medicine Fish. How does Medicine Fish seek to foster in Tribal youth the relationship between the Wolf River and Menominee cultural identity through fly fishing?

Menominee translates to People of Wild Rice, a name given to us by the Ojibwe because wherever we would move, the rice would follow. We spent a majority of our time on this water, and we gained all of our sustenance from the abundance of wild rice and sturgeon, which no longer freely exist. The early writers that came to articulate us as a people said that the Menominee people wouldn’t survive without fish—that it was something we needed all the time. We speared and had many ways of harvesting fish. That deep relationship is something that has been forgotten and developed into more of a sport fishing practice. It is now time for us to write our own stories, and that requires reigniting our relationship with our human and more-than-human kin. My brother and I understood what fishing and this desire to be outside did to heal us. So medicine is really what it is. It helps you heal, and our Medicine Fish logo tells the story of the medicine wheel and fish together. Following Red Road teachings of Gene Thin Elk, we use concepts of healing – mental, physical, spiritual, emotional – connected through the seven directions in relationship to all living things and all of creation. This model helps us gain the understanding of our values as Indigenous people and starts to bridge the gap between our creation, our language, our current thought processes, and how we view our relationship with the land today.

“Through our model of ‘heal-build-inspire’ we ground our understanding of our relationship to creation through water. It helps us connect to not only the Wolf River, but all the river systems that we’re connected to.”

Through the Medicine Fish model, we strive to prevent the disconnect of people from water and land by revitalizing their cultural importance. Through water we are helping young people establish their identity and a positive path forward. And when you think about fish, they exist in water – the one thing that connects everything. And water has memory and fish are like caretakers of that water. Through establishing that relationship between humans and fish and remembering that this isn’t just a sport thing – that there is so much more in your relationship to fish because you have to understand the water and all the living organisms that are inside of it. Especially through fly fishing! You’re not throwing a plastic or a rubber artificial lure that is made out of bright colors with vibration to trigger their predatory instinct. You’re trying to mimic something that is actually a part of creation. Using your artistic capabilities to do that and then learning what is in that water, it helps you realize that there’s so much connected to water. Water is important to bison, to sturgeon, and our people as well since the beginning of our existence. Even today as human beings, we begin our existence in water inside of our mother’s womb, and to look at all of the different ways that water is connected to life, how our people would travel by it, you realize how important it actually is. Through our model of “heal-build-inspire” we ground our understanding of our relationship to creation through water. It helps us connect to not only the Wolf River, but all the river systems that we’re connected to. We are also reintroducing bison to our people, which experienced the same loss of land that we did, to help improve health disparities and reconnect our people with other traditional lifeways.

Through Medicine Fish, you take kids on these incredible journeys of a lifetime and show them that they have a lot of the lessons already within them, and you help them build community and build a connection to place. I’m curious what lessons you’ve learned from the kids in your program.

One of the greatest lessons is understanding my own role as a father and my role as a community relative dealing with complex human beings who are all unique. I really have to look and find different ways to center us all, to be able to understand purpose, and that to have anything in this life you have to give it first. So many people approach these problems like they have all the answers because they are educated in psychology, sociology, human development and treatment, methods, and approaches. But there’s not a single approach that fits all of our life’s challenges. That’s one of my greatest learnings is knowing that you have to be willing to adjust at all times. The other great thing that I found in working with the kids in our program is to trust your intuition and that spiritual love that lives inside of you. They can really help you make decisions that sometimes blow you away because you followed something that was right and connected to some of the right people or made a decision that put the kid in a place where they were able to acquire a tremendous amount of healing or self-value. When you have those moments, that all comes from trusting what exists inside of us. That’s one of the most profound and empower- ing experiences to have. The individual that connects to themselves in their purpose has the ability to have a tremendous impact on everyone around them –if they’re open to it.

What messages do you hope to share with the Wilderness and the Wild and Scenic River communities?

On this land, written all over it, are signs that we are of the Earth. In today’s world, it is important that open-minded and willing people take the time to understand the Indigenous view and our relationship with the Earth to help us all heal our mother. It’s not just us as Indigenous and Tribal people, but actually all people should share this understanding and connection. It’s great to see that there’s people willing to learn and understand how our team at Medicine Fish works with others in this effort to protect and preserve nature. None of this work would exist if it wasn’t for relationship—relationships with each other, the natural world, and our ancestors. We need to make sure that we understand the why of what we’re doing and what we’re leaving behind, that we understand the relationships of the original inhabitants of landscapes here in this country, and the ancestors that have gone on before. This is all connected—we are all connected. Mother Earth is a source of life and we need to remember this so that we can heal ourselves and our world together. They say that we don’t own this time and space—we borrowed it from our future generations, our young people that are coming behind us. We have to leave this place in the best way so our children can have water and clean air to breathe. We need to heal our historical traumas together so we can demonstrate what it would look like to work together.

About Medicine Fish

Medicine Fish is a 501(c) 3 nonprofit organization based on the Menominee Reservation, Wisconsin. Our motto is Heal-Build-Inspire, and our vision is a world where youth and other community members are empowered to reconnect with equitable and traditional lifeways and knowledge systems, that include the restoration of land and waters through bison and sturgeon. We use a model that emphasizes our Menominee relationship with bison, land, water, and plants as persons and important beings of creation. We focus on Menominee and other Indigenous knowledge for decision-making about environmental and social well-being to secure a safe and healthy world for future generations. You can learn more at http://medicinefish.org.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you from Bryant to Gene Thin Elk for helping me find my purpose and the late Robert Perez, my fly fishing elder, mentor, and friend. This work was supported in part by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute. The perspectives in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or US Government determination or policy.

About the Authors

BRYANT WAUPOOSE JR. is the founder of Medicine Fish, an innovative and proven approach that uses fly fishing and Indigenous concepts to connect youth to creation and promote wellness through the model Heal, Build, and Inspire. Bryant has enhanced the quality of life for Indigenous youth through the revitalization of their cultural connection to self and Mother Earth, and he works to bridge mental health with Indigenous knowledge to create cultural coherence between worlds; email: bryant@medicinefish.org

LAUREN REDMORE is a research social scientist with the USDA Forest Service Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute where she uses her training in environmental anthropology to better understand how to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion in wilderness and wildlands.

References

Hitch, G., and M. Grignon. 2023. A forest of energy: Settler colonialism, knowledge production, and sugar maple kin- ship in the Menominee Community. American Quarterly 75(2): 251–277.

Kline, K. S., R. M. Bruch, and F. P. Binkowski. 2009. People of the Sturgeon: Wisconsin’s Love Affair with an Ancient Fish. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. 2004. Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin: Facts and figures reference book. https://menominee-nsn.gov/CulturePages/Documents/FactsFigureswithSupplement.pdf.

Menominee Tribe of Indians v. United States, 91 F. Supp. 917 (Fed. Cl. 1950).

Morales, R. 2017. Traditional agricultural practices of the Menominee Nation. POSOH Project, University of Wisconsin, Madison. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oeQfziJpdl8.

Read Next

Reflections on Wilderness 60 Years after the Civil Rights and Wilderness Acts

America’s dominant narrative of the origin of a beloved wilder- ness often centers Aldo Leopold in a heroic fight at the turn of the century against rapid industrialization that occurred at the expense of nature.

Removing the Wilderness Illusion: Emerging Professionals Explore Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in Wilderness

From the eyes of four emerging professionals in land management come four different wilderness stories.

Wheelchairs in Wilderness: One User’s Perspective on Ways to Improve Wilderness Accessibility for All

Lately, I’ve had a strong desire to return to my favorite wilderness area and attempt the area’s rim-to-river trail.