SWS Wilderness Fellow Diana Boudreau in the Ashdown Gorge Wilderness, UT; Photo Credit: Andrew Jackson.

Measuring Forest Service Wilderness Character Trends with Partners

Stewardship

December 2018 | Volume 24, Number 3

Wilderness Character Monitoring

Summer 2018 marked the official start of USDA Forest Service Wilderness Character Monitoring (WCM) implementation. Dubbed the “Pilot Year,” 2018 was the culmination of years of research, pilot testing, and interagency coordination. A centralized approach, extensive partner contributions, and local staff prioritization culminated in a successful implementation year, with baselines established for 7% of Forest Service wildernesses.

Since 1964, the four US federal wilderness-managing agencies have created policies and guidance to prevent the degradation of wilderness character, as mandated by the Wilderness Act. However, up to the mid-2000s, none of these agencies had established a process to evaluate if their management strategies were effective in preserving wilderness character. In particular, the long-term trends were difficult to measure. Starting in 2001, the Forest Service chartered a Wilderness Monitoring Team with representatives from all four agencies to answer this question and create a strategy to monitor if wilderness character is being preserved. The first national monitoring strategy was published in 2005.

In 2008 a team of interagency and academic professionals published Keeping It Wild (KIW): An Interagency Strategy for Monitoring Wilderness Character Across the National Wilderness Preservation System (Landres et al. 2008), and later its replacement, Keeping It Wild 2 (Landres et al. 2015), which provided a strategy for monitoring trends in wilderness character. These documents formed the basis of WCM for all four US land management agencies.

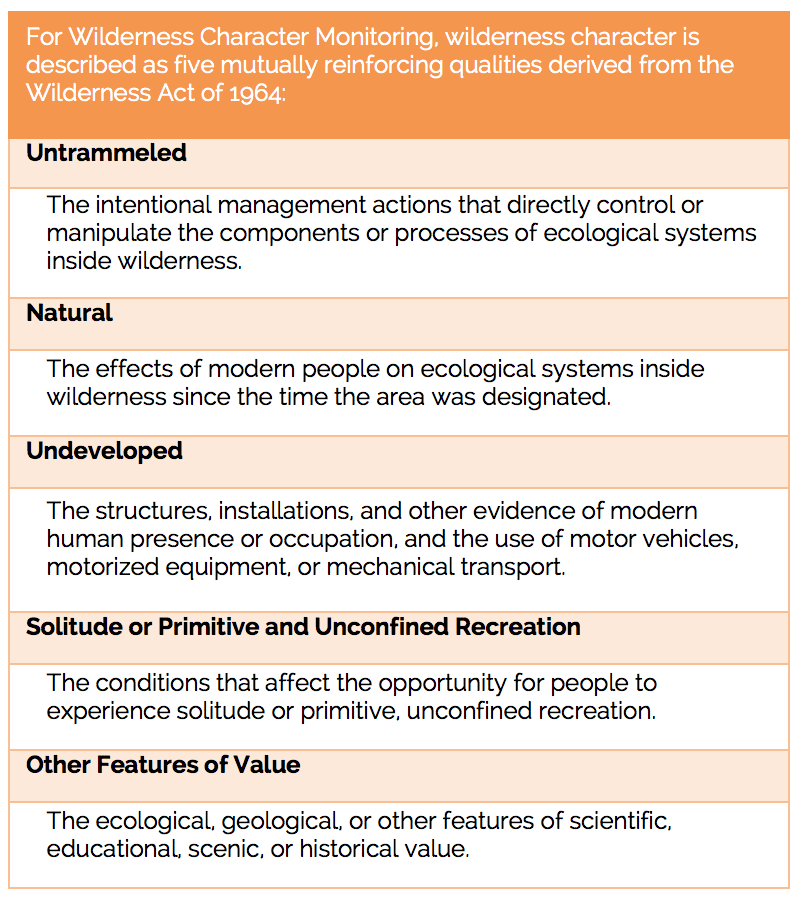

KIW and KIW2 utilized the statutory language of the 1964 Wilderness Act to identify five qualities of wilderness character that form the foundation of the current monitoring strategy. These qualities include: (1) Untrammeled, (2) Natural, (3) Undeveloped, (4) Solitude or Primitive and Unconfined Recreation, and (5) Other Features of Value (Table 1). Wilderness Character Monitoring consists of monitoring questions, indicators, and measures for each of the five wilderness character qualities. Measures are designed to analyze potential threats for each indicator to understand trends for each monitoring question. Trends for each measure are assessed as upward/improving, stable, or downward/degrading. When threats to a measure decrease, wilderness character is improved, and when threats increase, wilderness character is degraded.

Each agency has developed a slightly different process for selecting measures. In the Forest Service, after years of testing the strategy laid out by Keeping It Wild 2, the agency-specific Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide was published in fall 2018. The Guide requires Forest Service wildernesses to monitor certain agency-standard measures, using at least one measure per indicator, and then allows local units to choose from different developed measures and protocol options. Once a wilderness manager selects relevant measures, the Guide directs the local unit to complete a baseline assessment that establishes the condition of the wilderness at the time of designation, either if the data exist or at the time the first time monitoring is conducted. Five years after a baseline is established, consistent guidelines are used to roll up indicator trends to assess the trend for the entire wilderness. This information can inform appropriate management actions to improve areas that show concern.

Along with choosing measures and completing a baseline assessment, Wilderness Character Monitoring also consists of compiling legislative and administrative history and documentation and preparing a wilderness character narrative. Legislative and administrative documentation is compiled into an organized central repository to concentrate wilderness information and help wilderness managers and other staff completing monitoring in the future. The wilderness character narrative is a holistic, affirmative description of the wilderness that provides a “sense of place” and addresses the intangible, symbolic, and spiritual values of the area that are often missed in the baseline assessment. The narrative is organized by wilderness quality and describes what exemplifies each quality as well as identifies what degrades the quality as well as likely future challenges to preserving the quality. These two steps set the stage for planning, management, and monitoring, and ideally are completed before selecting measures and writing the baseline assessment since they are likely to inform which measures are selected.

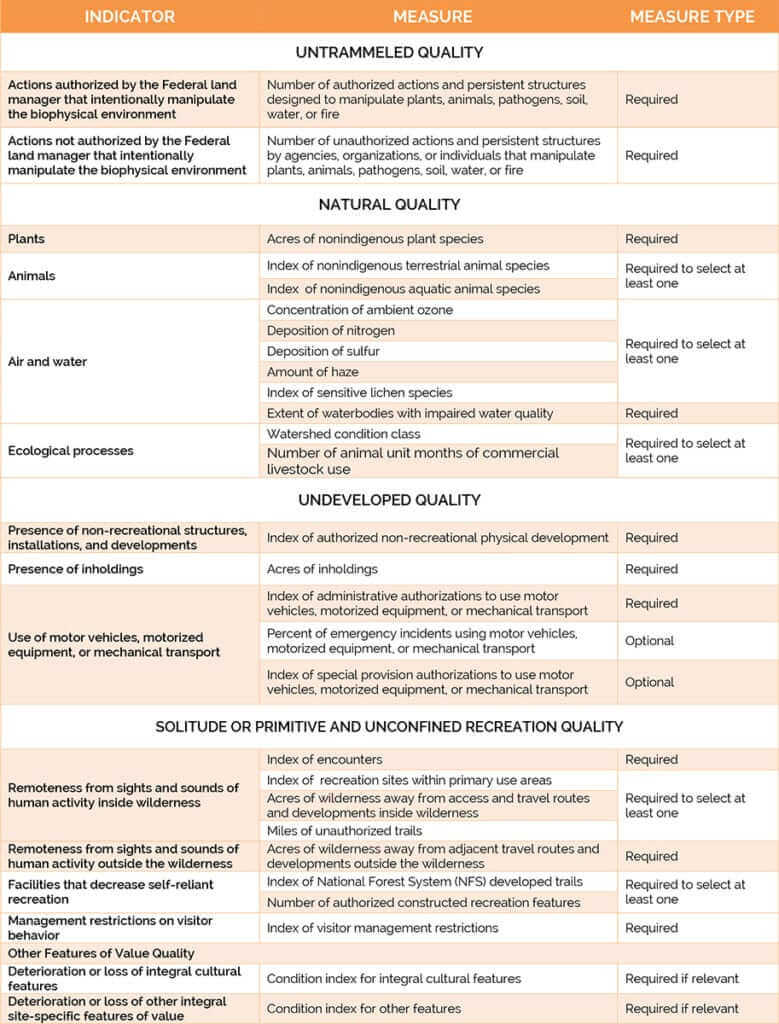

The Technical Guide encourages the use of available data to determine how wilderness character is changing over time. In the Forest Service, each wilderness must monitor at least 15 measures; however, there is flexibility for local units to choose from a range of potential measures as well as develop their own locally developed measures on top of the required number (Table 2). The intent was not to collect additional data but rather to use the best available science and to pick measures that represent important issues or challenges for that area. For example, in some cases staff wanted to develop local measures to reflect unique conditions affecting individual wildernesses – such as the presence of wind turbines (sight and sound impacts) on forest land directly outside of the wilderness boundary.

In addition to complying with the law, Wilderness Character Monitoring links the results of stewardship activities and on-the-ground wilderness conditions to the mandates of the Wilderness Act. Managers can then use WCM results to establish priorities for stewardship actions and determine whether the local unit or the agency as a whole is preserving wilderness character. Wilderness Character Monitoring also improves wilderness stewardship by providing wilderness managers with important information on how individual wilderness character attributes are changing over time.

In this pilot year, wilderness staff and partners collaborated to guide 29 wildernesses through compiling wilderness documentation, writing wilderness narratives, selecting measures, and establishing wilderness character baselines.

Table 2 – List of Forest Service Wilderness Character Monitoring measures (adapted from the WCM Technical Guide, 2018)

Over the next five years all 445 Forest Service Wildernesses are slated to complete this process, with 20% of wildernesses establishing baselines each year.

A nationally based Wilderness Character Monitoring central team was established to complete high-complexity, low-frequency tasks to reduce the burden on local units. The team consists of a central data analyst, two monitoring leaders, a database analyst, and the national Wilderness Character Monitoring manager. The data analyst was tasked with gathering national data such as air quality and watershed condition class information and working to develop statistical analyses. The central team leaders assisted with development of technical guidance and helped local units with tasks. The national manager, data analyst and the Wilderness Information Steering Team (WIMST) tested a new database that pulls existing resource information and allows for wilderness managers to enter local data for some measures. Central team members input measure data into a contractor-developed interagency database, from which trend reports can eventually be pulled. Several training materials were also developed, including templates, step-by-step instructions, and PowerPoint presentations. The central team held weekly virtual office hours to assist participants with learning databases, selecting measures, and answering technical questions. An evaluation plan was developed to address lessons learned in the pilot year and to implement changes for 2019.

Figure 2 – SWS Wilderness Fellow Matt Quinn in the Nellie Juan-College Fiord Wilderness Study Area, AK; Photo credit: Matt Quinn.

Partners

Although Wilderness Character Monitoring was designed to complement existing agency monitoring programs and use appropriate existing data whenever possible, the tasks involved can easily overburden local units that have many competing priorities. Partner organizations have become valuable resources at local, regional, and national scales. These partner organizations increase agency capacity, and in 2018 they helped ensure a successful official start of Forest Service Wilderness Character Monitoring implementation.

In the summer of 2018, three partner organizations worked with the Forest Service to complete Wilderness Character Monitoring work – largely the Society for Wilderness Stewardship (SWS) and the Southern Appalachian Wilderness Stewards (SAWS). The New Mexico Wilderness Alliance (NMWA) also has been involved, with a specialist completing baseline assessments for several Southwest wildernesses during 2018. All partner organizations employ highly educated and trained young professionals – SWS hires Wilderness Fellows and SAWS hires Wilderness Specialists – and place them across the country to assist local units. Fellows and specialists were hired to match agency needs, and are trained extensively before heading out to local units. Of the 29 pilot wildernesses, 22 had partner assistance in 2018.

Figure 3 – SAWS Wilderness Specialist Warren Carver, and Kyle Grambly, recreation program manager on the Chatthoochee-Oconee National Forest. Photo credit: Deborah Byrd.

The Wilderness Fellow and Specialist application process is highly competitive, and attracts applicants with master’s degrees and agency seasonal work experience. Participants generally work from May to November, and may move frequently between wilderness units. Past participants have gone on to work seasonally or permanently for land management agencies.

This partnership-based program is primarily funded by internal Wilderness Stewardship Performance funds and by partner contributions. Wilderness Stewardship Performance tracks agency wilderness actions and is closely tied to Wilderness Character Monitoring, which monitors the impacts of those actions. Pilot wildernesses without partner assistance also received a small amount of funding to help with agency staff time.

Training for the Fellows and Specialists consisted of a weeklong course based on the principles and guidance in Keeping It Wild 2 and the Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide. Participants met in two remote locations and practiced writing narratives, choosing measures appropriate to a case study wilderness, and spent time in the field speaking with Forest Service wilderness rangers and other staff on wilderness management challenges.

The use of partners to complete wilderness monitoring projects is not a new idea, and Wilderness Fellows have been placed in wildernesses for the past nine years across the country and in three of the four wilderness-managing agencies (USDA Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and National Park Service). With the help of Wilderness Fellows, the Fish and Wildlife Service has completed baseline assessments for all 71 of their wildernesses, and the National Park Service has completed more than a third of their baseline assessments. For the past seven years Wilderness Fellows have been placed in Forest Service wildernesses, working on completing wilderness character narratives and baseline assessments.

On the partner side, involvement in Wilderness Character Monitoring grew naturally out of existing relationships regionally and locally. Partners had been working with the Forest Service on wilderness stewardship for years, and the pilot year offered an opportunity to expand on existing knowledge and expertise. Partners completed hiring, conducted training, and developed standard operating procedures based on prior years’ wilderness work for the effort. Mentorship was provided by program coordinators, and weekly check-in calls with all participants ensured that support was available.

Lessons Learned

Since the intent of Wilderness Character Monitoring was to use existing information and not to collect additional data, in many cases gaps were identified in the corporate databases once staff and partners began the process of measure selection. In these cases the data were either missing, incomplete, or in error. This highlighted the importance for local units to review their data, particularly for the required measures, prior to embarking on implementation and to coordinate with specialists since there are often multiple data stewards for different resources within wilderness. It also highlighted the fact that monitoring plans for certain resources are in many cases more limited in wildernesses than in general forest areas where projects are more often proposed.

The untrammeled quality provided the liveliest discussion among 2018’s implementers. The Technical Guide requires that all trammeling actions, both authorized and unauthorized, must be counted every year and monitored over time. The Guide provides examples of situations both inside and, more rarely, outside of wilderness that are considered as trammeling actions. However, questions arose from unique situations, such as dams outside the wilderness that flood small areas within the boundary, or fire suppression adjacent to the wilderness boundary. In addition, participants had to consider scope and scale when assessing which actions to include as trammeling for monitoring purposes. Ultimately, asking two key questions assisted in determining if an action should be counted as trammeling: was there an opportunity for restraint, and was there intent to manipulate the Earth and its community of life within wilderness. Even with this guidance, local units occasionally had to make decisions for unique situations.

Another issue involved recognizing scientific advances that could change current Wilderness Character Monitoring measures. An example is air quality. Currently, the Technical Guide includes monitoring nitrogen and sulfur deposition; however, Forest Service specialists now believe that monitoring critical load exceedance is more important. Dealing with changes to measures to reflect these advances, and the impact on obtaining five-year-trend information if measures change during that time period will be a continuing process.

On the partner side, there were also lessons learned. Forests receiving partner assistance must be able to provide housing, office space, use of vehicles, and computer access for Fellows and Specialists, along with the required government trainings and background checks. All these steps took a significant amount of organizational and logistical time from the local staff to ensure a smooth transition.

Once the Fellows and Specialists were on the ground, considerable coordination was needed with the local unit and resource specialists to compile documentation, choose appropriate measures, ensure data accuracy, and determine the existing wilderness condition. Often, Fellows and Specialists were tasked with completing narratives and assessments for several wildernesses in the same region, necessitating their ability to work independently and efficiently to learn multiple areas and connect with local staff in a short amount of time. Since most of this work occurs during the summer months it is especially difficult to connect with field-going specialists and staff that are called on for fire support. In the future it may be more beneficial to start wilderness work in the fall and winter while staff are likely to have more time to assist with compiling documentation, verifying and correcting data, and reviewing drafts.

As more partner organizations become involved with Wilderness Character Monitoring, there will be a need for training coordination and standard communication practices in order to ensure that practices are applied consistently across all regions. An evaluation of this pilot year is planned for January 2019 to assess what worked and what could be improved.

Overall, there was a high level of enthusiasm during this pilot year among all participants, which was a great asset to implementation. Sue Spear, Forest Service national director, Wilderness and Wild and Scenic Rivers, summed up the past year when she said, I’m excited and pleased to see the level of commitment and enthusiasm for Wilderness Character Monitoring from all levels of the Forest Service and our partners. This 2018 pilot year has been both challenging and inspiring and I am looking forward to continuing implementation until all 445 wildernesses have a baseline and we can, for the first time, see trends in how our stewardship actions are affecting wilderness character.

MARY EMERICK is a natural resource specialist who served as the Forest Service National Wilderness Character Monitoring manager during the pilot year of USDA Forest Service WCM implementation. Her background is in wilderness and recreation planning; email: Memerick@fs.fed.us.

JACOB WALL works for the Society for Wilderness Stewardship as a Wilderness Character Monitoring leader on the WCM Central Team. Last year he worked as a Wilderness Fellow in Idaho; email: J.wall@wildernessstewardship.org.

References

Landres, P., C. Barns, J. G. Dennis, T. Devine, P. Geissler, C. S. McCasland, L. Merigliano, J. Seastrand, and R. Swain. 2008. Keeping It Wild: An Interagency Strategy to Monitor Trends in Wilderness Character Across the National Wilderness Preservation System. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-212. Fort Collins, CO: USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Landres, P., et al. 2015. Keeping It Wild 2: An Updated Interagency Strategy to Monitor Trends in Wilderness Character Across the Wilderness Preservation System. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-340. Fort Collins: USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Available at http://www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/pubs/49721.

Landres, P., S. Boutcher, and E. Mejicano. tech. eds. 2018. Wilderness Character Monitoring Technical Guide. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-XXX. Fort Collins, CO: USDA, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Read Next

Apologizing for Science-Based Decision Making in Protected Area Management

Apologizing for science promotes autocratic management that can easily be commandeered by sociopolitical agendas and bureaucratic systems.

Wilderness Giant: Stewart “Brandy” Brandborg Moves on at 93

Steward Brandborg was a phenomenal wilderness champion, the last wilderness advocate with ties to most of the founders of the modern wilderness movement.

Cultural Meanings and Management Challenges: High Use in Urban-Proximate Wildernesses

As outdoor recreation increases in popularity and metropolises grow larger, the issues facing urban-proximate wilderness and protected lands will continue to come to the forefront.