Mountain chamois in French Pyrenees. Photo by Sergio Cerrato-Italia from Pixabay.

Increasing the Acreage of Strictly Protected Areas in France

BY COORDINATION LIBRE EVOLUTION

Communication + Education

October 2024 | Volume 30, Number 2

Editor’s note: In France, a variety of strategies in favor of naturalness, free evolution (translation of the French term “libre évolution”), feral nature, rewilding, or non-intervention management (Locquet 2024; Génot and Schnitzler 2013) have emerged in the management of private and public lands in recent decades. This is mostly due to the initiatives of different NGOs and public institutions with little direct government regulatory intervention at the national level. As part of an ongoing series to showcase the diversity of initiatives that exist and/or are being created in France, IJW has obtained permission to publish an English translation of an op-ed signed by the leading members of the Coordination Libre Evolution (CLE) that was published in the French national newspaper Le Monde in December 2022. CLE is a coordinated network of organizations and stakeholders promoting the development of areas in free evolution in France. The organization was launched in 2021 just after the publication of its manifesto (CLE 2021) as an op-ed in Le Monde. According to CLE, “An area in free evolution is an area governed by natural processes. It is unmodified or only slightly modified and without intrusive or extractive human activity, settlements, infrastructure or visual disturbance” (CLE 2022; Wild Europe 2022). The 2022 op-ed showcases one of the multiple facets of the current development of natural/ wild/free evolution areas in France.

An Urgent Need to Increase the Surface Area of Protected Areas

Faced with the sixth mass extinction and climate change, which took on unexpected proportions in France with this summer’s wildfires (French wildfires of summer 2022), we urgently need to take action to adopt a strategy that can address the current challenges and improve nature protection in our territory. The French government has set a target of placing 10% of its territory under strong nature protection by 2030.

This French notion of strong nature protection does not correspond to the strict protection desired by the European Union (EU), which provides a much higher level of protection. The EU’s Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 requires each Member State to place 10% of their territory under strict protection, which means no extractive activities (logging, grazing, hunting, fishing).

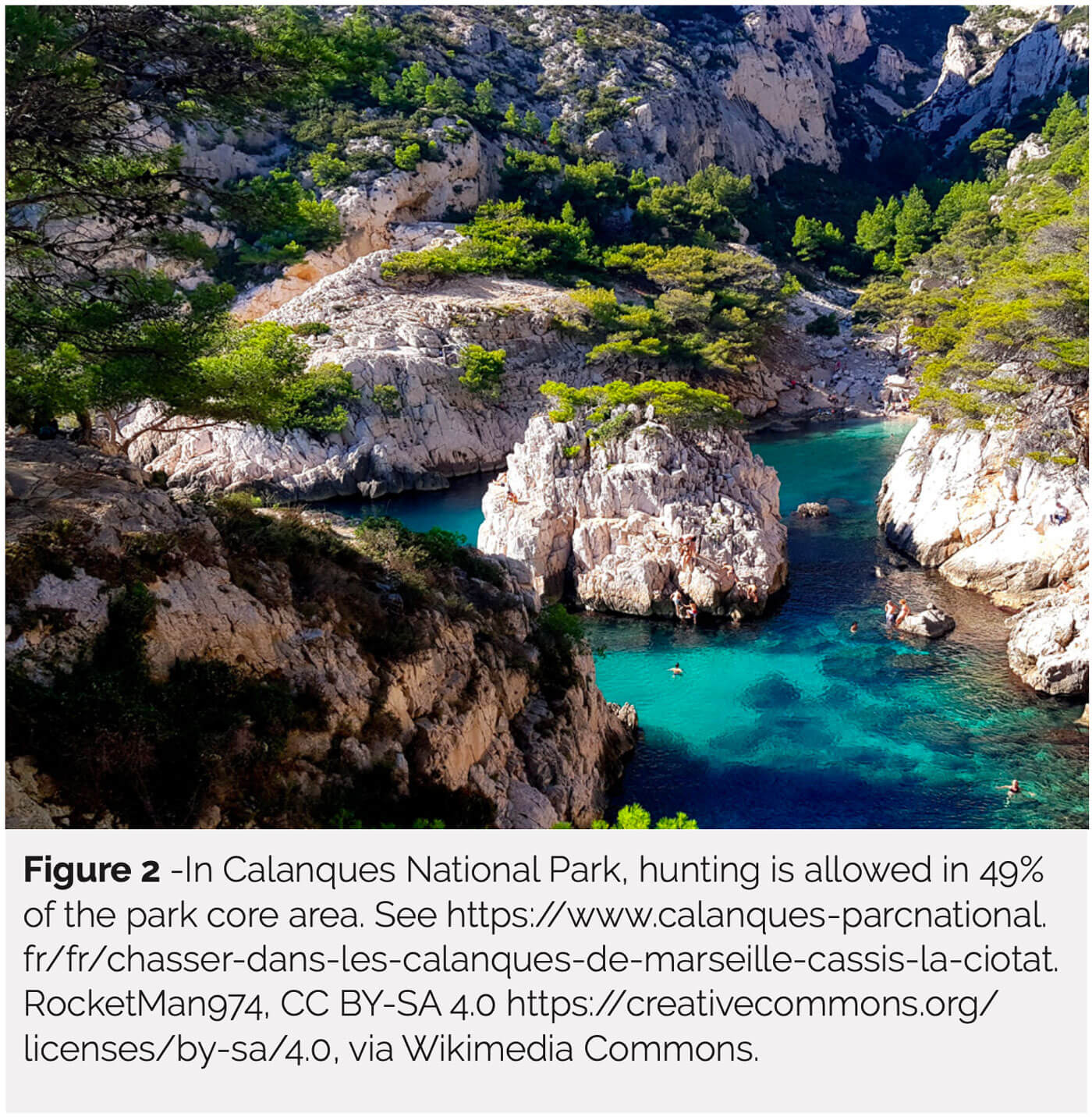

For a long time now, livestock grazing and timber harvesting have been allowed in the heart of French national parks, as well as in the majority of nature reserves, and hunting is permitted in nature reserves, integral biological reserves, and certain national parks (Figure 1).

1.54% of French Territory Is under “Strong” Protection

Yet strong protection should imply protected areas that are truly dedicated solely to nature and its evolving ecological processes, and not activities such as livestock grazing, timber harvesting, and hunting. In France today, less than 1.54% of the metropolitan land area benefits from “strong” protection. Today, the free expression of natural processes is ensured on only 0.6% of France’s terrestrial territory.

Less than strong protection leads to negative effects. For example, livestock grazing in national parks results in the decline of numerous plant species, soil erosion, eutrophication of high-altitude lakes and meadows, destruction of wetlands, competition between livestock and wild ungulates (ibex, chamois, deer, mouflons), and the disappearance of insects due to the use of environmentally toxic and persistent chemicals in the treatment of livestock against parasites. Timber harvesting automatically leads to declines in species that only live in forests and depend on dead wood and old trees. Hunting makes wildlife watching more difficult and artificially favors hunted species, such as wild boars, which threaten ground-nesting avifauna, or deer, which have non-negligible impacts on the vegetation in poor soils (Figure 2 ). Finally, hunting can lead to the illegal shooting of large predators (bears, wolves, lynxes), which are perceived as undesirable competitors.

Real Wildlife Sanctuaries

In the face of climate change and extinction of species, it is urgent to increase the surface area of protected areas, but above all, to extend the practice of free evolution – no logging, pastoralism, hunting, or fishing – inside these areas. These protected areas in free evolution ensure the effective preservation of the species that live here and promote the development of spontaneous ecological processes over the long term (primary production, herbivory, predation, necrophagy, decomposition of organic matter, disturbance, etc.), which tends to make ecosystems more complex and resilient.

They also enhance carbon sequestration in woody vegetation and undisturbed soils. Finally, they truly fulfill their role as wildlife sanctuaries if they host ungulates and their predators (bear, wolf, lynx), or encourage the return of these species due to the absence of conflicts with human land use, thus creating robust food webs capable of reacting positively to global changes and ensuring effective predation and dispersal of large herbivores.

A Socioeconomic Asset

Protected areas in free evolution have many benefits. For example, it is time to demonstrate the ecological role of the wolf in a natural ecosystem; the wolf is capable of limiting the numbers of wild ungulates through predation and dispersal of animals that are always on the alert, thus forcing these animals to exert a more diffuse impact on vegetation – the so-called “ecology of fear.” Protected areas in free evolution would allow measurement of the direct and indirect benefits of the return of large predators, particularly in terms of regulating ungulate and mesopredator populations and the natural regeneration of forests.

Protected areas in free evolution are also an asset in socioeconomic terms. They are low maintenance. They are attractive for nature tourism. They have educational and scientific interests as witnesses to global change, providing valuable information for sustainable natural resource management in neighboring areas. For example, less than 10% of forest fires are of natural origin. Fire risks are more moderate in natural forests, especially in large ones as these favor evapotranspiration and the aerosols that initiate rain. Except at high altitudes, natural forests are mostly made up of hardwoods, which burn much less easily than softwoods. Deadwood, which is a characteristic of forests in free evolution, abounds in moisture. Large trees contribute to heat dissipation; the undergrowth and different levels of vegetation protect the ground from heat, and deep soils retain rainwater. Thus, these forests can demonstrate the important ecological function of natural ecosystems in a time of climate change.

Questioning Our Domination of Nature

On an ethical level, free evolution calls into question our attitude of domination over nature. According to philosopher Virginie Maris (2018), nature can be seen as an “exteriority” enabling us to “limit our empire.” For the philosopher Baptiste Morizot: “Free evolution is not an enclosure, but the preservation of evolutionary potential, resilience and spontaneous ecological dynamics necessary in and around themselves.”

This increase in the surface area of strictly protected areas in France can foster essential and rich dialogues between citizens, NGOs, socio-professionals, and institutions as well as shared reflections, to build the very future of the territories concerned by these areas.

Signatories

Toby Aykroyd, director of Wild Europe

Gilbert Cochet, president of Forêts sauvages

Eric Fabre, cofounder of Association Francis Hallé pour la forêt primaire

Emmanuel Forichon, vice president of France Nature Environnement (FNE) Midi-Pyrénées Jean-Claude Génot, vice president of Forêts sauvages

Marc Giraud, spokesperson of Association pour la protection des animaux sauvages (ASPAS) Michèle Grosjean, president of Alsace Nature

Francis Hallé, botanist

Michel Jarry, president of FNE Auvergne Rhône-Alpes

Salvatore La Rocca, copresident of Lorraine Nature Environnement

Jean-François Petit, president of Libre Forêt

Julie de Saint Blanquat, president of Etats sauvages

Valérie Thomé, vice president of Animal Cross

Acknowledgements

Tina Tin wrote the Editor’s Note and translated the original text of the op-ed from French to English. Tina thanks CLE for their permission to translate and publish their text, and especially Richard Holding (ASPAS) for help in securing the permission and Alexandra Locquet for help in translation.

COORDINATION LIBRE EVOLUTION is a coordinated network of organizations and stakeholders promoting the development of areas in free evolution in France. Their website is https://www.coordination-libre-evolution.fr/.

References

CLE. 2021. Let’s make room for true nature. https://www.wildeurope.org/wp-content/ uploads/2023/06/Lets-make-room-for-true-nature-2.pdf.

Génot, J.-C. and A. Schnitzler. 2013. Rewilding France via feral nature. International Journal of Wilderness 19(2): 30–33, 48.

Locquet, A. 2024. Wilderness Babel: On the impossibility of translating “wilderness” into French. International Journal of Wilderness 30(2): pages 48-53

Maris, V. 2018. La part sauvage du monde: Penser la nature dans l’Anthropocène. Seuil.

Wild Europe. 2022. A working definition of European wilderness and wild areas. Update of September 9, 2022. https://www.wildeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ Definition_25062013-update-151120.pdf.

Read Next

Missing the Forest for the Algorithm

What is the value of wilderness? Well, what you have just completed reading is the “value of wilderness” as described by ChatGPT 3.5.

Rewilding Prerequisites: An Ecocentric Approach

Rewilding is increasingly gaining momentum as a conservation practice in Europe.

Trusting Tech and Wilderness in the 21st Century

A Response to Keeling’s The Trouble with Virtual Wilderness