Science & Research

December 2015 | Volume 231, Number 3

by H.KEN CORDELL, RAMESH GHIMIRE, and CHAD P. DAWSON

Introduction

How the public and managers value wilderness areas has been an important inquiry as it is a measure of support for the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS) (Cordell et al. 2005). Recently published results of surveys of the public and wilderness managers are compared based on a survey of a sample of the U.S. population and from a national study of wilderness managers. Reference to wilderness in both surveys is specifically to the NWPS. While these surveys were conducted in different years (2008 and 2014, respectively), both are relatively current and the list and phrasing of the 13 wilderness values used in each survey were the same.

Wilderness values data from the survey of the general population was generated through the National Survey on Recreation and the Environment (NSRE) (Cordell et al. 2008). The NSRE was an ongoing series of surveys that began in 1960 as the National Recreation Survey and then eventually became the NSRE, which was last administered in 2012. The NSRE was set up as a general population, ran- dom-digit-dialed household telephone survey designed to measure environmental attitudes of Americans. Public par- ticipants in the survey represent a random, cross-sectional sample of noninstitutionalized residents of the United States, 16 years of age and older. One of the questions asked survey participants in 2008 to rate the importance of 13 identified wilderness values on a five-point scale, from not at all important to extremely important.

Wilderness values data from the survey of the general population was generated through the National Survey on Recreation and the Environment (NSRE) (Cordell et al. 2008). The NSRE was an ongoing series of surveys that began in 1960 as the National Recreation Survey and then eventually became the NSRE, which was last administered in 2012. The NSRE was set up as a general population, ran- dom-digit-dialed household telephone survey designed to measure environmental attitudes of Americans. Public participants in the survey represent a random, cross-sectional sample of noninstitutionalized residents of the United States, 16 years of age and older. One of the questions asked survey participants in 2008 to rate the importance of 13 identified wilderness values on a five-point scale, from not at all important to extremely important.

The results pertaining to wilderness wilderness values held by federal managers of the NWPS were obtained through administration of the National Wilderness Managers Survey (WMS) (Ghimire et al. 2015a). Between February 24 and May 19, 2014, responses were received from 368 federal managers of the NWPS in the Forest Service (FS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM), National Park Service (NPS), and Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). Requests to all agency field and regional units responsible for area management within the NWPS were sent by a national representative of each of the four federal land management agencies asking that all their personnel charged with wilderness management duties respond to the survey. Both the WMS instrument and its administration were managed online through SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com). Completed surveys were forwarded by respondents through SurveyMonkey to team members at the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia, for analysis. Data were analyzed and reported by the USDA Forest Service and University of Georgia team members in Athens to both the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute and the Arthur Carhart Wilderness Training Center in Missoula, Montana. One of the questions asked managers in 2014 to rate the importance of 13 identified wilderness values on a five-point scale, from not at all important to extremely important (Ghimire et al. 2015b).

Measuring Wilderness Values

Perspectives of the public versus manager respondents were somewhat different. Public survey participants were responding with how important each value is to them personally; for example, valuable in order that they personally have the option to visit wilderness areas. Manager participants were responding with how important each value is in management of the NWPS; for example, valuable in order that the public has the option to visit wilderness areas. Because the question frameworks were otherwise identical, a comparison is possible between how the population of the United States and how federal wilderness managers rated the importance of each of the 13 values.

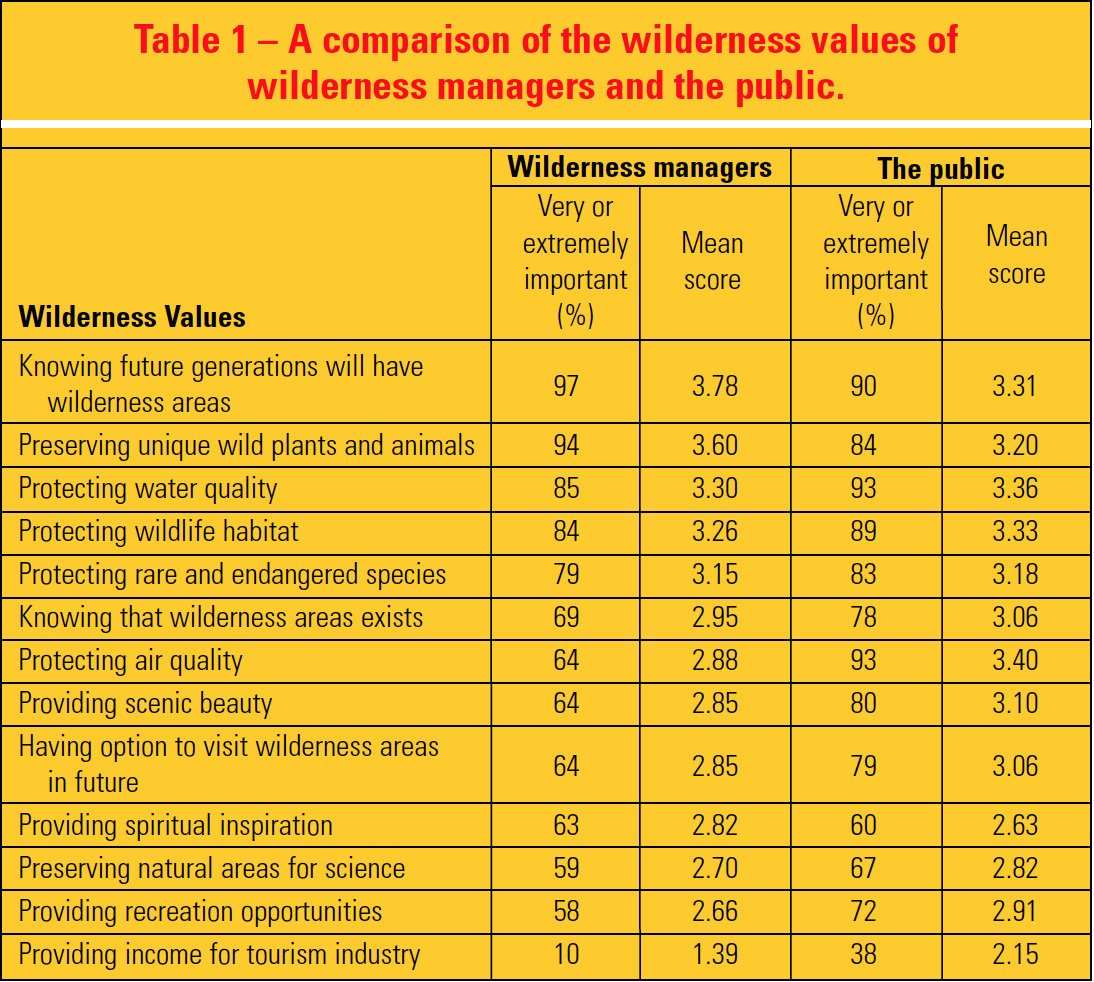

In both the NSRE and WMS surveys, the respondents (wilderness managers and the public) were pro- vided a five-point scale from not at all important (= 0), slightly important (= 1), moderately important (= 2), very important (= 3), to extremely impor- tant (= 4) as the response to rate the importance of preserving wilderness areas for each of these statements. In Table 1 the column headings labeled “very or extremely important” summarize the percentage of respondents (managers or the public) that rated the wilderness values statements very or extremely important. The column labeled “mean score” is the average score for that value based on the respondents rating on the five- point scale. The 13 values are listed in Table 1 in order from highest to lowest mean score based on the managers’ scores. However, ranking by the percentage of public respondents who rated values very to extremely important resulted in a very similar ranking.

The Comparison

A comparison of percentages of the managers and of the public rating the importance of the same 13 wilderness values revealed some differences (Table 1). While the largest percentage of managers placed greatest importance (very or extremely important) on wilderness for the reason of knowing future generations will have wilderness to visit or otherwise appreciate, the largest percentage of the public placed greater importance (very or extremely important) on wilderness for protecting air quality and protecting water quality. Both managers and the public placed the least importance on wilderness for the reason of providing income for the tourism industry. Although managers and the public rate wilderness values somewhat differently, they both view wilderness as noneconomic resources.

In order by highest mean scores, the top five rated wilderness values by managers were as follows:

- Knowing future generations will have wilderness areas

- Preserving unique wild plants and animals

- Protecting water quality

- Protecting of wildlife habitat

- Protecting rare and endangered species

Wilderness managers most highly rated knowing that future generations will have wilderness to visit (bequest value). They also listed very highly the stewardship of wilderness resources. In this survey, rare and endangered refers to legally designated species under the Endangered Species Act.

In order by highest mean scores, the top five rated wilderness values by the public were as follows:

- Protecting air quality

- Protecting water quality

- Protecting of wildlife habitat

- Knowing future generations will have wilderness areas

- Preserving unique wild plants and animals

Two values stand out in the public’s response to the NSRE wilderness values questions as being very or extremely important: protecting air quality and protecting water quality.

Figure 1 – Wilderness managers have professional experience and training in understanding wilderness values. U.S. Forest Service rangers kayaking in Harriman Fiord within the Nellie Juan/ College Fiord Wilderness Study Area of the Chugach National Forest, Alaska. Photo by Kevin Hood.

Wilderness includes natural lands with creeks and rivers flowing from them that provide natural filters to make air and water cleaner, both inside and outside wilderness areas (ecological services). The public also highly rated knowing that future generations will have wilderness to visit (bequest value). Two additional values stand out; more than 80% indicated they are very to extremely important: protecting wildlife habitat and preserving unique wild plants and animals.

Some differences are evident between the percentages of respondents reporting a value as very to extremely important in each survey and between the mean score in each survey. However, no statistical testing was conducted between the survey data sets because the intent was to see the order in which the values would be ranked and whether respondents in each survey would rate the values equally highly. The rank ordering of the 13 values of wilderness were remarkably similar between the two surveys in spite of the different per- spectives of the wilderness managers (focused on public needs and values) and the public survey (focused on personal needs and values).

The two most important differences from comparing these two surveys are (1) 58% or more of wilderness managers and 72% or more of the general public respondents rated 12 wilderness values as very or extreme important, and (2) wilderness managers and the public were generally in agreement on which are the most important wilderness values.

Implications

While differences in value ratings between managers and the citizen public are not huge, they do nonetheless exist. There are two ways to look at and interpret these differences. One is to acknowledge that managers are likely more knowledgeable about the condition of the wilderness areas they manage, and of the policies and their professional management options, than is the public. Thus, perhaps managers’ ratings and rankings should be looked at as more relevant and perhaps should carry more weight in agency policy and management practice decisions. Another way to look at the differences is to acknowledge that the NWPS is citizen owned. Thus, perhaps the owners’ ratings of wilderness values should carry the day. However, the best management policy and practice should consider both manager and public perspectives. As long as the intent and legal direction of the 1964 Wilderness Act is honored, it seems there is a need both for more manager and public engagement as a means to see and allow these differences to play out in agency policy.

Figure 2 – The public generally values wilderness whether they are visitors or not. Here a hiker stands in the wave rock formation in the Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness managed by the Bureau of Land Management in Arizona and Utah. Photo courtesy of Mike Salamacha.

H. KEN CORDELL is scientist emeritus at the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute and the Southern Research Station, Athens, GA; email: kencordell@gmail.com.

RAMESH GHIMIRE is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Georgia, Athens, GA; email: ghimire@uga.edu.

CHAD P. DAWSON is professor emeritus at the College of Environmental Science and Forestry, State University of New York, Syracuse, NY, and IJW editor in chief; email: chad@wild.org.

VIEW MORE CONTENT FROM THIS ISSUE

References

Cordell, H. K., J. C. Bergstrom, and J. M. Bowker. 2005. The Multiple Values of Wilderness. State College, PA: Venture Publishing, Inc.

Cordell, H. Ken, Carter J. Betz, J. Mark Fly, Shela Mou, and Gary T. Green. 2008. How do Americans view wilderness? Retrieved November 15, 2014, from http://warnell.forestry.uga.edu/nrrt/nsre/IRISWild/ IrisWild1rptR.pdf.

Ghimire, R, G. T. Green, H. K. Cordell, A. Watson, and C. P. Dawson. 2015a. Wilderness stewardship: A survey of National Wilderness Preservation System managers. International Journal of Wilderness 21(1): 23–27, 33.

Ghimire, R.; H.K. Cordell; A. Watson; C. Dawson; G.T. Green. 2015. Results From the 2014 National Wilderness Manager Survey. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-336. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 96 p