Digital Review

Reviewed by Patrick Kelly, Media And Book Review Editor

Wilderness Digest

December 2023 | Volume 29, Number 2

by RAYNA BENZEEV, DIEGO MELO, and DEVON REYNOLDS

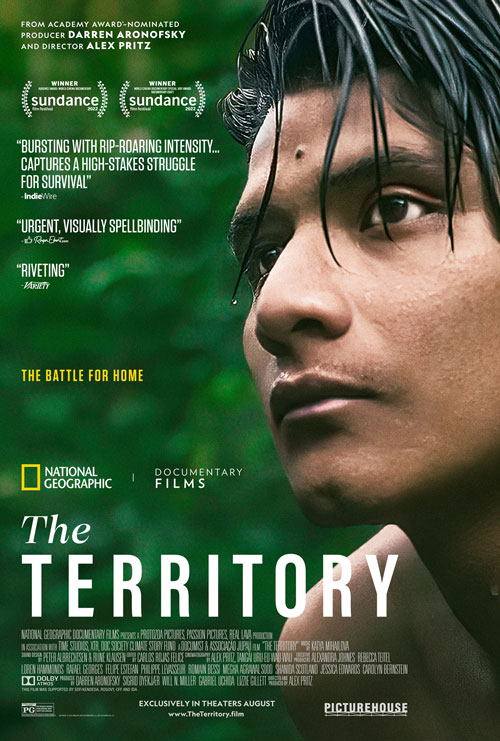

The Territory (2022), a National Geographic (NatGeo) film, provides a glimpse into the Indigenous fight to defend lands in the Brazilian Amazon. Through a vivid film style that evokes walking amongst those who traverse the forest, viewers become members of the story by piecing together the mysteries underlying land grabbing and deforestation. The protagonists, the Uru-eu-wau-wau people, resist invasions from all sides like the steadfast leaf-cutter ants that persistently march through the jungle. In this way, wilderness is conceptualized as a place where ecosystems and culture can coexist. In stark contrast, settlers make claims to territory in a fast-paced and industrial wild-west landscape, fueling the march of extractive technology that expands settler colonialism. As viewers are guided to piece together the global significance of land grabs and deforestation via large-scale satellite time-lapses and scenes of burning landscapes, NatGeo invites us to honor life and support Indigenous struggles to defend their worlds.

For the Uru-eu-wau-wau, technology is the primary defense tool employed in the war against Indigenous land. Contrary to the misconception that Indigenous peoples are ancient beings that live entirely removed from society, The Territory illustrates how the Uru-eu-wau-wau defend their claim to the land through advanced technologies. Drones, GPS devices, and film equipment allow them to broadcast their stories through the documentary itself. In fact, the gaze behind the camera shifts dramatically when a film crew made up of members of the Uru-eu-wau-wau people reclaim the film and become the filmmakers. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Uru-eu-wau-wau excluded all outsiders from their lands, including NatGeo filmmakers–which significantly transformed the narrative. The film shifts from semiposed shots of landscape, people, and forest wildlife to shots that provide direct evidence of invasions to be presented to the outside world. This reversal of the gaze, where the Uru-eu-wau-wau become the creators of their own story, challenges stereotypes from outsiders that perpetuate romanticized views of Indigenous ways of living and being.

The film adds a layer of novelty to the deforestation story by zooming intimately into the lives of multiple characters from diverse and sometimes conflicting vantage points. Viewers are shown the firsthand intricacies of the lives of a persevering activist of Indigenous rights and territorial claims (Neidinha), a diplomatic settler attempting to legally squat on Indigenous land (Sergio), a settler attempting to illegally claim Indigenous land (Martins), as well as members of the Uru-eu-wau-wau, including a bold teen leader (Bitaté) and the tactical leader of the autonomous Indigenous guard (Ari). By taking a deep dive into life on the Amazon frontier, viewers are exposed to the complexities and competing motivations acting on the land including those relating to lifestyle, religion, rural/urban dynamics, and aspirations for conquest.

Despite its novelty, the film’s strategy of solely promoting firsthand and observational accounts of land grabbing and deforestation leaves out an essential part of the story. By presenting a “both sides narrative,” The Territory is unable to show how wealthy and powerful actors drive Amazonian deforestation. It is often the agribusiness owners that cause oppressed people to be pitted against each other and to risk their lives, while the powerful have very little to risk. Many end up being exploited, while the exploiters remain invisible. In other words, the colonial system that feeds upon intense competition for the privatization of lands remains unaddressed at a systemic level. Because wealthy landowners driving land grabs remain hidden in the film, viewers could mistakenly leave believing a simpler story, that deforestation is caused by marginalized actors who each deserve their own access to land. While the film provides a glimpse of the role that regional Brazilian elites play in the deforestation process through local electoral politics, the film could have provided a more in-depth investigation.

The film additionally stimulates viewers to rethink the way that society prioritizes production and efficiency of land. At one point in the film, Sergio (a settler) says, referring to the Uru-eu-wau-wau, “They don’t farm, they just live there,” implying that using land for farming is the only legitimate use of land. By making production the goal, colonial settlers promote a narrative where only those that produce on land deserve rights to land. Indeed, Brazil’s legal code has long enshrined this philosophy, supporting land grabbers’ achievement of land titles through squatting on and cultivating the land for a long enough time. As Martins (another settler, working through illegal means) says, “Eventually the government will support us but only after we’ve done the work.” By arguing that the Uru-eu-wau-wau have so much land that “they can’t even walk in it,” settlers are able to use production as a tool to justify their own land claims and to perpetuate further acts of settler colonialism. Learning about this process leaves viewers with the question: Is the Indigenous way of being with land, one focused on defense, protection, and small-scale extractive use, still valid even though it does not fit cleanly into the capitalist economic model? In 2023, there must be no room for ambiguity. Indigenous peoples’ struggles for land and sustainable resource use, like the Uru-eu-wau-wau’s struggle, lead the way in how we might survive the behemoth of climate change and capitalism’s voracity.

Supporters of Indigenous rights in the Brazilian Amazon, however, have no choice but to risk their lives and the lives of their families. Neidinha (the environmental activist) experiences a deadly kidnapping threat against her daughter because of her work supporting Indigenous defense. Ari is killed during the course of the film and his murder remains unsolved today. In a context where there is no police enforcement of Brazilian law and no political support on the ground, brave individuals put their lives in grave danger as they support Indigenous rights. As noted in the film, the Indigenous affairs agency that is supposed to provide oversight is like “shit in water.” When allies are silenced, the Uru-eu-wau-wau are left even more alone in defense of their forest, an island amidst the sea of pastures and invaders.

Although the film is a success story for the Uru-eu-wau-wau, who were able to form a monitoring team that seamlessly arrested invaders, there are still far more invaders than Indigenous people and outside pressures are high. The only 180 remaining Uru-eu-wau-wau had to grapple with COVID- 19, which killed 5% of the entire territorial population in just 10 days. In the future, new emerging threats could render Indigenous peoples even more vulnerable. As the film says, “It would be like a genocide for them.”

By highlighting a local problem with global relevance, The Territory ignites a call to action to support Indigenous autonomy and territorial rights. Despite the success of the Uru-eu-wau-wau in their monitoring efforts, it is a massive risk to form and maintain such a team, and many other Indigenous communities may not want to take on such a task. As the film showed, when the Brazilian government failed to enforce the Constitution, which guarantees the rights of Indigenous people to territory above even federal land claims, illegal deforestation and land grabs were able to take over. The film therefore becomes a call to hold the government, organizations, and police forces responsible to do their jobs, so that other Indigenous leaders and allies across Brazil do not have to risk their lives to keep their livelihoods.

Although there have been some improvements for Indigenous rights since the 2022 Brazilian election, the onslaught against Indigenous land claims remains across Brazil today. The fight for land in the ever-expanding Amazon frontier is nowhere near over. If invasions continue unfettered with governmental complicity, the perverse tactic of genocide via deforestation will continue to expand. While small but mighty Indigenous monitoring teams and their allies will fight on, The Territory pushes us to make this struggle our own. Climate change makes us all dependent on Indigenous success.

The Territory is available on Hulu and Disney+.

RAYNA BENZEEV is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California–Berkeley with a focus on reforestation and land rights for Indigenous and traditional communities in Brazil; email:Rayna.benzeev@berkeley.edu

DIEGO MELO is a queer political ecologist and a PhD candidate in geography at the University of Colorado– Boulder; email:diego.melo@colorado.edu

DEVON REYNOLDS is a PhD candidate in environmental studies at the University of Colorado–Boulder, and works to support environmental justice movements through research, writing, and policy work; email:devon.reynolds@colorado.edu

Read Next

Reflections on Wilderness 60 Years after the Civil Rights and Wilderness Acts

America’s dominant narrative of the origin of a beloved wilder- ness often centers Aldo Leopold in a heroic fight at the turn of the century against rapid industrialization that occurred at the expense of nature.

Removing the Wilderness Illusion: Emerging Professionals Explore Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in Wilderness

From the eyes of four emerging professionals in land management come four different wilderness stories.

Medicine Fish Is Leading the Way to Heal, Build, and Inspire Menominee Youth through the Wild and Scenic Wolf River: An interview with Bryant Waupoose Jr., Founder of Medicine Fish

From a bird’s eye view, the Menominee Reservation is a forested oasis in sharp relief from neighboring landscapes of dairy farms spanning northeastern Wisconsin.