Photo credit: veeterzy on Unsplash

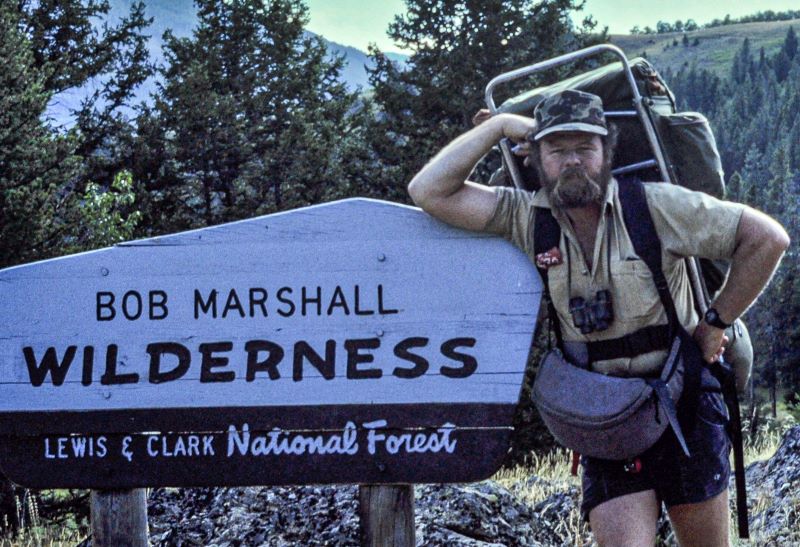

Dave Foreman: Remembering a Father Tree

Stewarship

December 2022 | Volume 28, Number 3

“Dave gave his storied life to protecting and restoring a wild Earth, for wildeors of all sizes, from small songbirds to giant redwoods. The mighty oak that was Dave Foreman has fallen to nourish new generations of rewilding leaders.”

Since Dave Foreman’s death from interstitial lung disease on September 19, the last group he founded, The Rewilding Institute (https://rewilding.org) has been flooded by fond remembrances and glowing tributes to his vast influence. A common theme in these grateful messages is: Dave Foreman changed my life. I saw him give a speech in (whatever the city or university or wilderness conference) and from then on, I dedicated my life to wild things and places.

Some of these messages from Dave’s close friends and colleagues have compared him to a giant tree in an old-growth forest. This metaphor I find particularly heartening, for as we all know now, big dead trees, standing or fallen, are as life-giving as are green trees. Dave is now like a mighty oak fallen in an old-growth gallery forest along the Gila River, southwest New Mexico, nurturing new generations of trees and their defenders, and guiding us as we work to protect and restore the Mogollon Wildway, linking the Gila Wilderness with Grand Canyon National Park, as part of the Spine of the Continent Wildway.

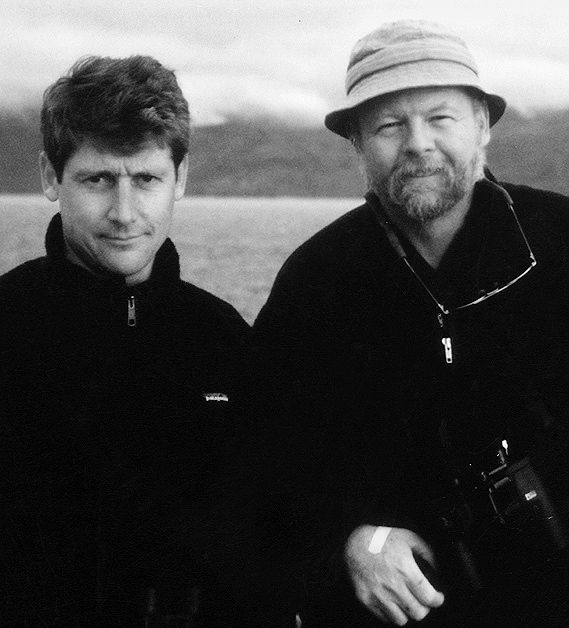

My own little conservation story hints at Dave’s influence. In college, I saw Dave and his fellow Earth First! co-founders Bart Koehler and Howie Wolke give hellfire & brimstone wilderness speeches at a rally for unprotected wildlands. The week I finished college, I hitchhiked across the country to volunteer in the Earth First! Journal office in Tucson, Arizona. I thought I’d do a year of service, then go back to school. Dave’s vision was too compelling. I could not leave. For nearly four decades now, I’ve been trying to help Dave implement his vision for rewilding North America. Thanks to Dave, I’ve lived a life incredibly rich in experiences, if occasionally lean in resources. Dave’s numerous friends and colleagues constitute a powerful community – like an old-growth ecosystem — of wildlands activists, biologists, and writers; and I’ve had the honor of meeting many of them, often at the home of Dave and his beloved wife Nancy Morton (affording me the opportunity to wash dishes for some of the finest people in the world!).

I was fortunate to get to know the soft side of Dave, as well as the more distant, heroic side. As a living legend, Dave could be intimidating. He had an encyclopedic memory for conservation and natural history and for public lands geography. He could name and describe virtually every species exterminated by our forebears in North America. He stopped timber sales on more National Forests than most Americans ever even have a chance to walk. With Howie Wolke, he completed the most comprehensive US roadless area inventory ever conducted (subject of their book The Big Outside). As a friend, though, and for many of us as a mentor, too, he was generous, funny, warm, and one of the best story-tellers we had ever heard.

Part of Dave Foreman’s great legacy will be courage. Dave was fearless in the face of bulldozers threatening ancient forests, critics falsely accusing him of not caring about people, and government agents who infiltrated Earth First! when the Reagan administration perceived us as a threat to economic growth. Dave taught us to speak boldly for what wild Nature really needs. He was not a revolutionary, however. Indeed, Dave was deeply conservative, believing that protecting our natural heritage and learning to coexist with our wild neighbors are core values shared deep-down by most thinking, feeling people. Dave always argued that conservation should be non-partisan – that folks from all political parties and walks of life should embrace wildlands and wildlife conservation.

Dave Foreman was famously controversial at times. His book Man Swarm: How Overpopulation is Killing the Wild World was a blunt look at how excess human numbers, in terms of population and consumption, are driving the extinction and climate crises. Some others of Dave’s writings were almost uncomfortably frank in how they criticized mainstream, foundation-supported conservation and environmental groups. Dave was sometimes an iconoclast, like his older friend Ed Abbey had been; and every movement needs that, discomfiting though their words can be.Perhaps the most enduring part of Dave Foreman’s legacy will be the rewilding movement. Dave coined the term ‘rewilding’ about a quarter century ago. His short definition of ‘rewilding’ was ‘wilderness recovery’; but he explained it at length in his landmark book Rewilding North America – the closest thing to a blueprint for how to achieve what are now called Half Earth goals on the most affluent continent. Dave grumbled often and laughed occasionally at how his neologism ‘rewilding’ had been adopted by manifold interest groups, ranging from drumming circles, to folks seeking spiritual enlightenment, to alternative medical practices teaching gut biome health. He occasionally chafed at the suggestion of some conservationists that rewilding start at small-scale levels, like restoring native plants to our yards. He practiced such healing local work himself, but did not see it as rewilding. Big, Wild, and Connected were the basic descriptors of rewilding for Dave; and he wanted to see projects protecting big core reserves and protecting or restoring the full range of native wildlife, including apex predators like wolves, big cats, bears, raptors, and sharks.

Like most brilliant people, Dave Foreman was complex and paradoxical, though, and I believe in the main, he was pleased to see work for other species expanding under the rubric rewilding. The final test for Dave on whether work lives up to the rewilding label was, does it served wild creatures – ‘wildeors’, or self-willed beasts, as Dave liked to call our furred, feathered, finned, and flowering neighbors.

Dave gave his storied life to protecting and restoring a wild Earth, for wildeors of all sizes, from small songbirds to giant redwoods. The mighty oak that was Dave Foreman has fallen to nourish new generations of rewilding leaders. Dave Foreman did not, in the flesh, live to see the day Wolves, Pumas, and Grizzly Bears in Mexico would have unbroken lineages north along the Spine of the Continent into Canada; but may the young rewilding leaders he will inspire achieve such big, wild, connected visions here and around the world.

For more on Dave Foreman’s life, please follow the link from the Resource Renewal Institute. https://vimeo.com/235470442, which brings Dave ‘to life’ in an interesting way.

Special thanks to Magnus Sylven of the Wild Foundation and Katie Shepard, Managing Editor and co-founder of Essex Editions for providing additional photographs, editing, and materials for this tribute.

About the Authors

JOHN DAVIS is the executive director of The Rewilding Institute, rewilding advocate, and member of the Adirondack Council; email: john@rewilding.org; jdavis@adirondackcouncil.org.

Read Next

December 2022

In this issue of IJW, we remember Dave Foreman as a father tree for wilderness. Carol Lee and Tanya Dreizin investigate peer-driven social pressures for behavior in rock climbers. Keely Fisher examines virtual reality and the impact of wilderness conceptualizations. Gracie Dunlap describes living along¬side the Yawanawá. And John Shultis uses creative expression and the arts to demonstrate the impact of wild places.

Reconnecting and Reengaging Wilderness Stewardship

We all adapted to changes, some societal and many personal, over the past several years. Now comes the opportunity to reconnect and reengage in our passions for wilderness and wild nature.

Temagami

We started as strangers, young and so naive; we had no skills, just learned on the way. Pushed off from camp, by Temagami; the adventure began, in the wilds.